Seventh tribe bans South Dakota Governor Kristi Noem

A seventh tribe in South Dakota, the Crow Creek Sioux Tribe, banned Gov. Kristi Noem on May 14.

During a Tuesday meeting, the Crow Creek Tribal Council voted unanimously to ban Noem from entering its central South Dakota reservation.

The decision comes on the heels of the Yankton Sioux Tribe’s decision to ban Noem on May 10 and the Sisseton Wahpeton Oyate’s banishment on May 7.

These bans have been made following the governor’s accusations that Mexican drug cartels are operating on tribal land in South Dakota. Noem also accused tribal governments of benefiting off of the alleged cartel presence and of failing their people, particularly youth.

Tribes are now exercising their sovereignty by indefinitely banning the governor from tribal lands in the state.

As sovereign nations, tribal governments are allowed to ban anyone from their lands. According to the Bureau of Indian Affairs, tribes possess the right to regulate activities within their jurisdiction, which includes the banishment of persons, Native or non-Native.

Previously when questioned about being banished from the Cheyenne River Sioux Tribe in early April, Noem’s Communication Director Ian Fury said Noem encourages tribes to banish cartels from tribal lands.

The Crow Creek Sioux Tribe’s decision leaves the governor only able to enter two of the nine reservations in the state, the Lower Brule Reservation in central South Dakota and the Flandreau Santee Reservation in eastern South Dakota.

The governor’s communications director did not respond to a request for comment about her recent banishments.

The Crow Creek banishment came moments after Noem announced the creation and appointment of a tribal law enforcement liaison.

Algin Young, the former police chief of the Oglala Department of Public Safety, was announced as the tribal law enforcement liaison on May 14. Young left his position on April 21 after his contract with the Oglala Sioux Tribe expired, interim police chief John Pettigrew said in an interview with ICT and the Rapid City Journal.

The post Seventh tribe bans Kristi Noem appeared first on Buffalo’s Fire.

50 years later, Lakota girl still missing

Amelia Schafer

ICT + Rapid City Journal

PINE RIDGE, S.D. — The walls of the Oglala Sioux Tribe Victim Services building are lined with missing person posters. Dozens of faces and names of men and women, all from the Pine Ridge Reservation, who have gotten little to no justice.

Fifty years ago in February 1974, Delema Sits Poor and her friend left their school at the Seventh Day Advent Church in the number four community (also called Wakpamni), about eight miles from the Pine Ridge community. The two set out to walk along an unpaved backroad towards Manderson, South Dakota. Despite below-zero temperatures, the two 12-year-old girls were determined to reach their destination.

High winds and heavy snow set in during their walk. At some point, Sits Poor’s friend began to develop frostbite so she opted to walk to the nearby Red Cloud Indian School, but Sits Poor kept walking, wearing only a white down-filled jacket with brown bell-bottom pants and sneakers. The Oglala/Mniconju Lakota girl was never seen again.

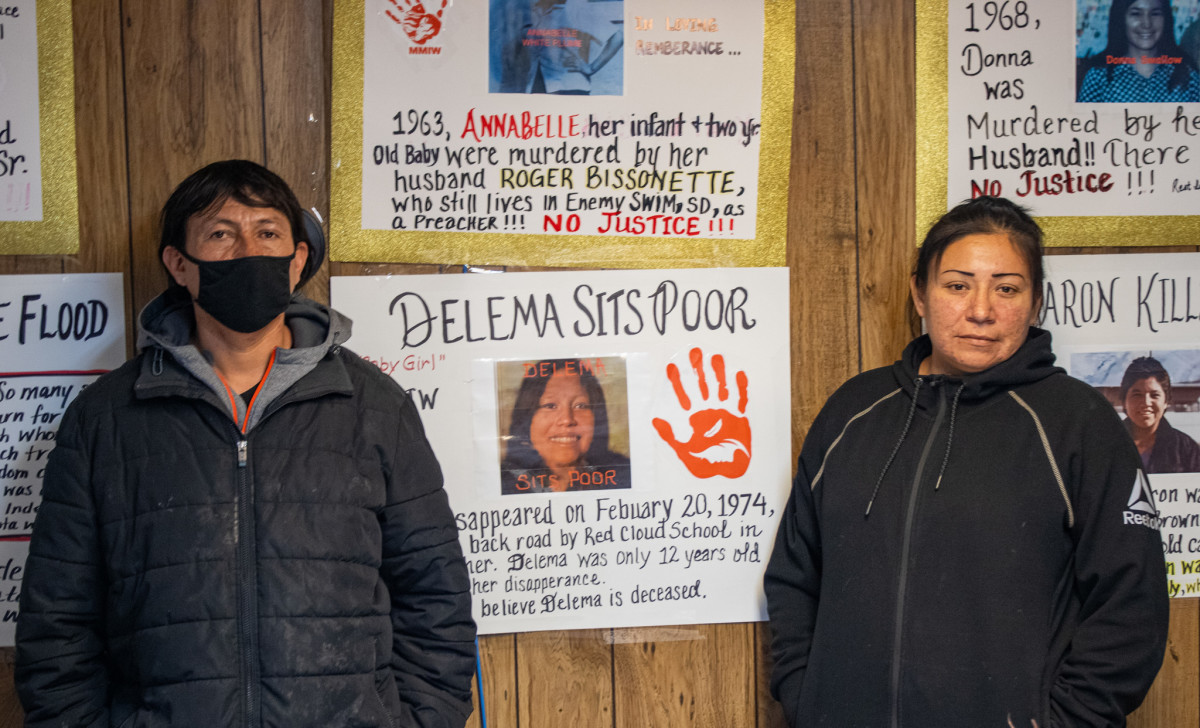

Delema Sits Poor disappeared after school at the Seventh Day Adventist Church in the number four community on the Pine Ridge Reservation in 1974. Sits Poor was heading to a friend’s house after school. (Photo by Amelia Schafer, ICT/Rapid City Journal)

The next morning, once the snowstorm cleared, her family traveled to Pine Ridge to find a phone and call for help. Her father filed a police report, and her cousin called the National Guard.

In the days following Sits Poor’s disappearance, ground and air searches were conducted around the Calico community where Sits Poor may have walked – a rugged remote area with miles of winding buttes, steep valleys and thick brush. Late last year a three-year-old boy was found alive after disappearing in the same area.

Family members said they felt that after the seventh day of searching the push to find Sits Poor ended.

“They just stopped looking, back in those days I got the impression that they weren’t very helpful,” Sits Poor’s cousin Genevieve Chase In Sight-Ribitish said. “We never got any responses from her missing person’s report we filed, no one came to ask us about her, we haven’t gotten any updates.”

On the 50 anniversary of her disappearance, the Sits Poor family continues to search for answers.

Bo Sits Poor and sister Tawny Eagle Louse pose next to an age-progressed photo of their missing aunt, Delema Lou Sits Poor. Sits Poor was last seen in 1974 heading to a friends house after school. (Photo by Amelia Schafer, ICT/Rapid City Journal)

“I tried looking for her many times, people would call and say they’d seen her in Rosebud or in Denver, and somebody told me they saw her around Pine Ridge with a man. I searched everywhere, we’d go everywhere,” said Sits Poor’s older sister Rose Thunder Club.

After seven years, Sits Poor was declared dead. The family suspects that foul play may be involved in her disappearance.

“We hang in there hoping that one day she would walk in the door or we’d see her around somewhere,” Chase In Sight-Ribitish said.

At only 12 years old, Sits Poor was just beginning to find herself. She was getting into rock music, her brother Frank Sits Poor said. She’d just gotten a new Lynyrd Skynyrd cassette tape.

“She was just 12, just a kid, just getting started,” Thunder Club said.

Raised by her grandmother, a fluent Lakota speaker, Sits Poor spoke Lakota and was engaged with her culture.

“Delema was a really beautiful person, she was caring and loving and kind, she never hurt anybody,” Chase In Sight-Ribitish said.

Sits Poor’s disappearance is among dozens of unsolved cases of missing and murdered Indigenous women in South Dakota.

Of the cases currently listed in the South Dakota Missing Persons’ Clearing House, 54 percent are Indigenous despite Indigenous people making up only 9 percent of South Dakota’s population.

The count listed in the Clearing House is also an undercount. Sits Poor is not listed and never has been, as well as a few other older cold cases from Pine Ridge. This is because they were never filed and added to the system, according to the South Dakota Attorney General’s Office.

Related: Public safety commissioner seeks change in Alaska’s MMIP response

Dozens of Indigenous women went missing and were murdered on the Pine Ridge Reservation in the 1970s. There’s no official number of how many women disappeared or were killed during this time. Sits Poor’s own mother, Phyllis White Dress was murdered in 1976, two years after her daughter’s disappearance.

One of the oldest cases, Beatrice Tallman-Curry, was brought to justice because her case piqued the interest of a law enforcement officer several years after her disappearance.

Delema Sits Poor’s missing person photo (left) beside the Oglala Sioux Tribe Victim Service’s age progression of her at 61 years old. Sits Poor was last seen in 1974. (Photo by Amelia Schafer, ICT/Rapid City Journal)

“There’s no one set or list of names, they’re all scattered everywhere,” said Susan Shangreux-Hudspeth, Oglala Lakota and director of Oglala Sioux Tribe Victim Services. “There’s just no justice. No one has been arrested. It takes someone dedicated to bringing this to justice.”

As time moved, young family members like Eagle Louse and her brother Bo Sits Poor never got to meet their aunt. While they never met her, they grew up with her by hearing stories about her. How helpful she’d been to her family, how much she loved her grandmother, how silly she could be.

“These are traumatic events for these families, all of these (cold cases) they have a story, she was somebody,” said Amanda Takes War Bonnett, Oglala Lakota and public education specialist for the Native Women’s Society of the Great Plains.

Sits Poor’s father, mother, grandma and several of her siblings died without answers.

“My grandpa went to the grave looking for her, my mom did too,” said Tawny Eagle Louse, Sits Poor’s niece. “It would just be nice to get some closure.”

Many aspects of Sits Poor’s disappearance are unknown. Some documents list her as last seen on February 4, 1974, while others list February 20. Additionally, it’s unclear if Sits Poor made it to her friend’s house and disappeared leaving, or if she never made it to her destination.

“It’s like finding a needle in a haystack,” Chase In Sight-Ribitish said. “There’s so many brick walls and things we don’t know.”

Sits Poor’s disappearance broke her father’s heart, Frank Sits Poor said.

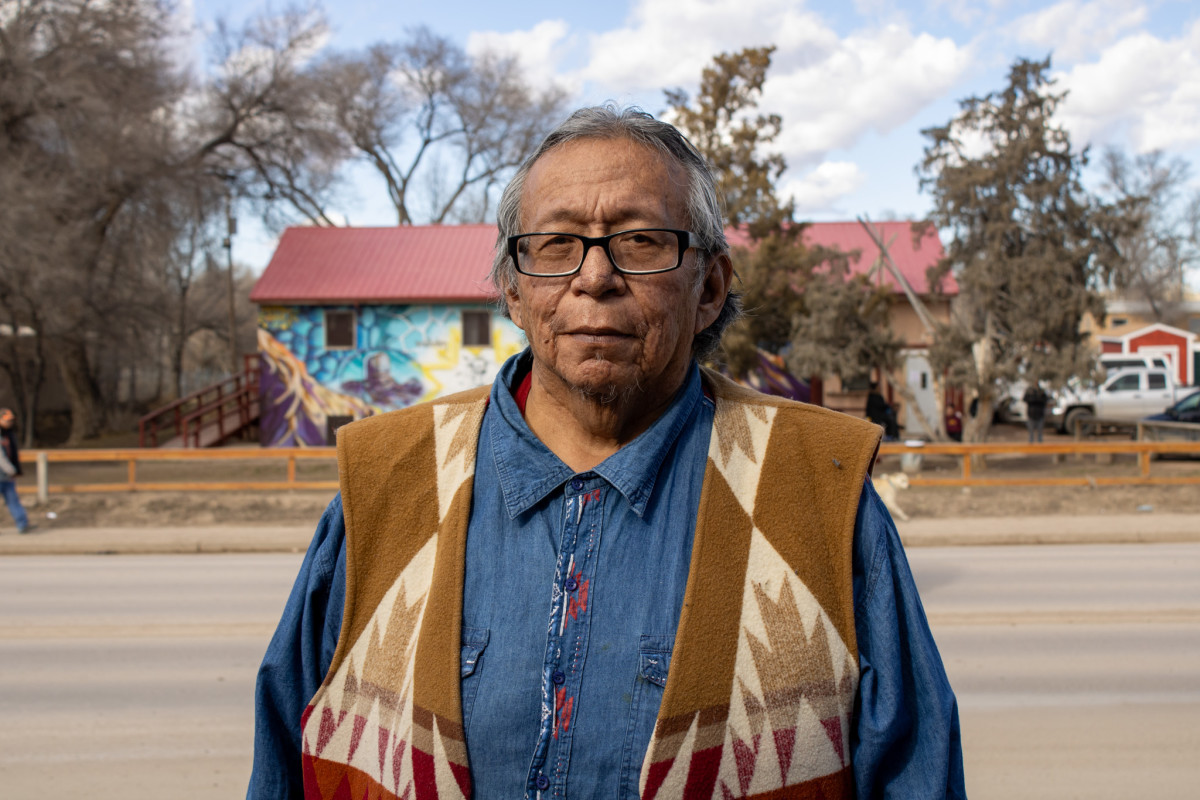

Frank Sits Poor is the older brother of Delema Sits Poor who was last seen in February 1974 heading to a friend’s house after school. (Photo by Amelia Schafer, ICT/Rapid City Journal)

“I think it tore my family apart when she disappeared, the love kind of dwindled,” Eagle Louse said.

Around 2018, Thunder Club and Chase In Sight-Ribitish said they were contacted by an investigator for the Oglala Sioux Tribe’s newly founded cold case unit. Despite speaking with the investigator a few times, they never heard back.

With no updates and limited information, the family continues to hope and pray for Sits Poor’s return.

“Every chance we get we go up into the hills and look,” Chase In Sight-Ribitish said. “Anytime the relatives get the chance they’ll go back there and look. Anything suspicious we move it around and look around for her.”

Anyone with information about Sits Poor’s disappearance can contact the Oglala Sioux Tribe Police Department at 605-867-5111 or report to the Beauru of Indian Affairs Missing and Murdered Unit by texting 847411 to BIAMMU or calling 1-833-560-2065.

This story is co-published by the Rapid City Journal and ICT, a news partnership that covers Indigenous communities in the South Dakota area.

Our stories are worth telling. Our stories are worth sharing. Our stories are worth your support. Contribute $5 or $10 today to help ICT carry out its critical mission. Sign up for ICT’s free newsletter.

City closes shelter for Natives amid arctic freeze

ICT is working to shape the future of journalism and stay connected with readers like you. A crucial part of that effort is understanding our audience. Share your perspective in a brief survey for a chance to win prizes.

Amelia Schafer

ICT + Rapid City Journal

RAPID CITY, S.D. – As temperatures dipped below zero Friday, January 12, Rapid City officials decided to close a makeshift warming shelter that was to serve Indigenous homeless people.

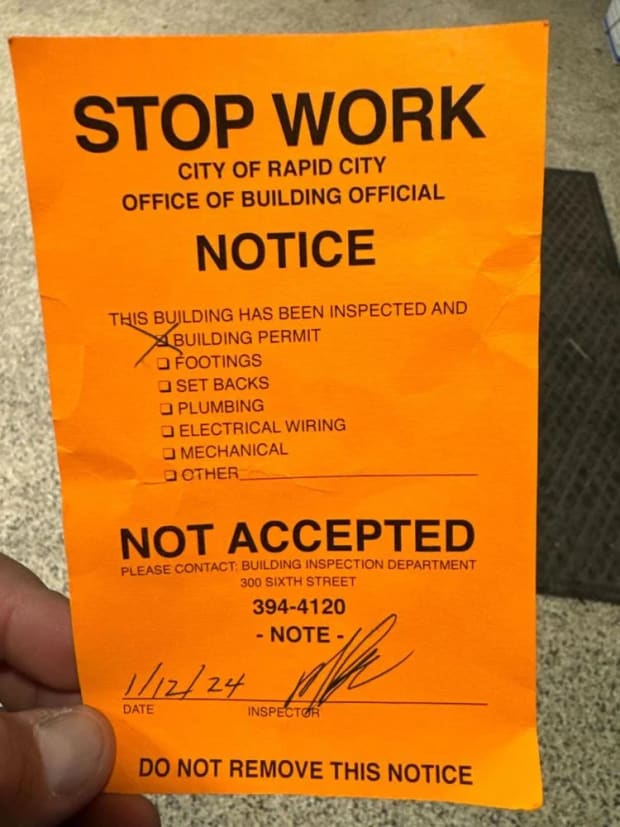

Two Native-serving nonprofits – Woyatan Lutheran Church and Wambli Ska Society – had planned to open the military grade warming tent as an additional shelter. But Friday afternoon, city administrators issued a stop work notice to organizers.

“When city staff went to the property to issue an order not to proceed with the use of that tent, it was with the acknowledgment that the permits had not been secured, but that we had a bigger crisis on hand,” said Vicki Fisher, Rapid City community development director. “We have a cold spree that we’ve not experienced in a long time. And we have a lot of vulnerable people that need to be sheltered. So the message was you don’t need to take down a tent. Just please don’t use it. It is so frigid that the action of trying to heat it would put those people in jeopardy of a fire.”

Around 4:30 p.m. Rapid City Police Officer John Olson, escorted by Lt. Tim Doyle, arrived to issue the stop work order. Chris White Eagle, leader of the Lakota Center at Woyatan Lutheran Church, spoke with Olson and Doyle and said he was told the Pennington County Jail could be used as a temporary shelter if the Cornerstone Mission and Care Campus hit max capacity.

“We looked at him like, ‘Are you saying that’s our option, to save your life you need to go to jail,’” White Eagle said.

Earlier on Saturday Rapid City Police Department Community Relations Director Brandyn Medina said that if all other options were exhausted, the Pennington County Jail could be used as a temporary shelter.

“I think they [Olson and Doyle] were speaking on generalities and talking about it on a broad spectrum,” Medina said. “It’s not saying that we would find charges to put somebody in the jail or charge them criminally so they could go into the jail, it’d be in a total noncriminal context. It would be simply using the extent of our resources to make sure that nobody was turned away into the cold.”

Later on Saturday, Medina said the county sheriff’s office clarified that the jail would not be used as a temporary shelter and that the existing resources would suffice.

A Facebook post from the Rapid City Municipal Government Saturday morning stated there is an “abundance of space” at city shelters.

“At no point since this cold snap began has the Care Campus or Mission been full or turned individuals away. Anyone seeking shelter during this frigid cold spell are reminded to seek shelter at either facility,” the post said.

Medina said law enforcement officers are conducting extra patrols to contact and transport individuals struggling with the cold.

Several local Native nonprofits had come together to serve homeless people following the closure of the Hope Center, a shelter that served mainly Native people. Those organizations are working to provide food, water and shelter to those who either cannot go to the Cornerstone Rescue Mission or the Care Campus or don’t feel comfortable going.

“A lot of them don’t like going on to the Campus. A lot of them don’t like going to the Mission,” White Eagle said. “The mayor is making it very clear that those are our resources, and that’s the only thing that they have.”

As a backup, the Lakota Homes Oyate Center has been opened for those in need of a warming shelter or a meal. Various Indigenous community groups will be serving meals at the Oyate Center throughout the day.

“If you call anywhere around the Native community right now, there’s people cooking, there’s people driving, there’s young men walking under the bridges,” said NDN Collective Founder and CEO Nick Tilsen. “We’re getting out of our vehicles. We’re helping the people, we’re getting rides and we’re trying to utilize every service that’s available. An army tent in the middle of winter is totally last resort.”

Our stories are worth telling. Our stories are worth sharing. Our stories are worth your support. Contribute $5 or $10 today to help ICT carry out its critical mission. Sign up for ICT’s free newsletter.

Voting rights at center of tribal dispute with city

The City of Martin, South Dakota and the Oglala Sioux Tribe are at odds over a public records request sent by the tribe.

The City of Martin has asked that the Oglala Sioux Tribe waive its sovereign immunity or pre-pay an undetermined amount of attorney fees and administrative fees for the records it requested. The South Dakota American Civil Liberties Union (ACLU) is challenging this through the South Dakota Office of Hearing Examiners.

On August 25, under the South Dakota Sunshine Act, the tribe requested records relating to potential violations of the Voting Rights Act of 1965, according to the South Dakota ACLU.

The initial request from the tribe asked for an extensive list of documents, each of which span a time range of 20 years, including election results, redistricting maps (boundary changes and reorganization plans), agendas from meetings where redistricting was discussed, any and all analysis of Section 2 of the Voting Rights Act or Gingles factors and more.

On September 11, the City of Martin denied the tribe’s request unless the tribe waived its sovereign immunity and paid upfront for time spent gathering records and attorney fees for 20 years’ worth of records. City representatives said the requested attorney’s fees were included as many of the records required an attorney’s assistance to locate.

After the denial, the tribe got in touch with the South Dakota ACLU. Working with the ACLU, the tribe narrowed the requested records down to a 10-year time frame from 20.

The tribe, represented by the ACLU, Native American Rights Fund and Public Council, is appealing the City of Martin’s stipulations before the South Dakota Office of Hearing Examiners.

The ACLU said the charging of attorney fees and request to waive tribal sovereignty are unreasonable.

“Why do they not want to produce these records without imposing these very stiff, punitive demands on the tribe like making them pay agreed to prepay attorneys fees in an unknown amount and also waive their tribal sovereign immunity,” said Stephanie Amiotte, legal director of the ACLU of South Dakota and a citizen of the Oglala Sioux Tribe, in a phone call. “It certainly begs the question, why aren’t they just producing these records as they would to any other requester if, in fact, everything is in accordance with the Voting Rights Act or the law.”

The City of Martin said it’s asking for attorney’s fees to be charged due to the nature of the documents requested.

“The requests are vague and broad, leaving it difficult for a layperson to determine whether a statutory exception applies,” said Sara Frankenstein, an attorney representing the City of Martin. “Many of the requests require legal analysis as to whether the documents sought are excluded from public disclosure pursuant to South Dakota law. Additionally, the request sought documents spanning over twenty years. Such a huge and broad request is taxing on the City of Martin’s resources and its citizenry. The City of Martin is small, and resources are thin.”

Generally, tribal sovereignty allows tribes to be free from lawsuits whether private or commercial, much like any other nation. The tribe is choosing to pursue action through the Office of Hearing Examiners because it says the conditions sought by the City of Martin are unreasonable or sought in bad faith.

The City of Martin’s legal counsel said the city requested that the tribe waive its sovereign immunity to ensure the request would be paid should it be fulfilled.

“Due to sovereign immunity, the City does not have legal recourse for collecting the applicable fee should the Tribe not pay, and the amount may be substantial if the ACLU continues to demand 20 years’ worth of broad-ranging documents,” Frankenstein said.

Frankenstein also said if the Oglala Sioux Tribe or ACLU refuses to pay for the records request or sovereign immunity is not waived, Martin taxpayers will have to foot the bill.

The ACLU said a request to waive sovereign immunity reflects a larger problem facing Indian Country.

“It really carries bigger implications than that because it amounts to a gradual erosion of the constitutionally protected status as a sovereign nation,” Amiotte said. “We see that every day in attempts by states to take that sovereign status away through encroachment on jurisdictional issues, and just other areas that tribes really do enjoy that status as a sovereign nation to govern in a manner that other governments are allowed to govern.”

Records shared with the Rapid City Journal and ICT suggest the City of Martin did share a January 2022 redistricting map with the tribe; however, no other records will be shared without pre-payment.

“The ACLU’s press release is wildly inaccurate,” Frankenstein said in an email to the Journal and ICT. “First, the City has yet to deny any document requested, other than broadly asserting a general denial that protected or privileged documents will not be disclosed, if the ACLU truly seeks them. The ACLU is not contesting the withholding of protected or privileged documents, so no denial of records is at issue here. In other words, there has been no ‘denial’ to trigger any judicial review.”

The City of Martin and Bennett County are within the exterior boundaries of the Pine Ridge Reservation and are considered by the Department of the Interior to be reservation land. State agencies, however, such as the South Dakota Department of Transportation, generally list Bennett County as not being within the reservation. Census records indicate roughly half of Martin’s population is non-Native.

In 2005, the South Dakota ACLU attempted to sue the City of Martin for Voting Rights Act Violations. After an 11-day bench trial, the claim was dismissed.

The post Voting rights at center of tribal dispute with city appeared first on Buffalo’s Fire.

Study Looks at Climate Change Effects On Rural Electrical Grids

Researchers from across the country are studying how to improve electrical grids across the country with a focus on underserved, rural communities.

Through a four-year, $750,000 grant from the National Science Foundation, South Dakota State University, University of Maine, University of Alaska Fairbanks, and University of Puerto Rico Mayague will examine how climate change affects electrical grids. The project is titled “STORM: Data-Driven Approaches for Secure Electric Grids in Communities Disproportionately Impacted by Climate Change.”

“The basic idea is to go to a few specific communities, and through community engagement, figure out what are the challenges that they are facing with regard to the impact of extreme weather on the power grid, and then solve some of those issues in terms of community outreach and engagement, designing new methods to make the grid more resilient,” said Tim Hansen, associate professor in SDSU’s Department of Electrical Engineering and Computer Science and co-principal investigator on the project.

Hansen said the research project is based in strategic locations in which different weather events occur. Alaska, for example, deals with extreme cold, while Puerto Rico deals with storms and flooding.

The common issue is that all the events impact the power grid, he said. “Our focus is on power grid resiliency from different perspectives.”

As part of the project, the researchers will work with community members on engagement. Hansen told the Daily Yonder it will be a ground-up approach so see what the community is willing to adopt.

Daisy Huang is an associate professor at the University of Alaska Fairbanks and mechanical engineer. She also conducts research at the Alaska Center for Energy and Power, which looks at optimizing power, mostly in rural communities around Alaska. She said the rural communities are mostly not connected to the state grid.

“So they’re all on their own diesel fired power plants. And so we look at ways to integrate renewables [and] optimize their diesel for maximum efficiency,” she told the Daily Yonder.

Huang said she is also interested in creating educational programs around STEM.

“The idea is looking from a community perspective – what their energy needs are, and how we can translate that – in parallel – developing educational programs around kids learning about energy systems, [like] engineering or STEM in general, math, physics.”

There will also be a virtual reality lab for remote power and energy research studies between all the participating institutions, Hansen told the Yonder.

He said that many of the researchers on the project are young investigators. “It’s a very good opportunity for the [National Science Foundation] to really build up the mentorship, and really build a lot of people’s long-term careers off of the back of this,” he added.

The post Study Looks at Climate Change Effects On Rural Electrical Grids appeared first on The Daily Yonder.

Hispanic population gains in rural counties spark South Dakota growth

Tribe bans Dupree educators from reservation over child abuse allegations

South Dakota rejects federal food funding despite 25,000 children going hungry

Sober living fraud scheme targeted Montana tribal citizens

When Autumn Nelson decided she was ready to seek treatment for her alcoholism, she knew she had to act fast.

“When someone with an addiction says, ‘I need help,’ we’re begging,” she said. “We want it.”

Nelson, who lives on the Blackfeet Reservation, knew she might have to leave home to get the help she needed. Crystal Creek Lodge provides inpatient and outpatient treatment on the reservation, but community members say the place is almost always at capacity. Journey to Recovery, another facility on the reservation, provides outpatient services primarily focused on supporting individuals after they return from inpatient treatment. And sometimes, it can be helpful for people struggling with addiction to leave their environment and disconnect from people in their circles who may be using.

So when Journey to Recovery gave Nelson the contact information for a treatment center in Arizona, Nelson was hopeful. She was ready to get clean. Little did she know she’d soon be caught up in a national scandal.

Phoenix House Recovery, a treatment center in Arizona, paid for Nelson’s plane ticket to Arizona, and Nelson was eager for a fresh start. Her father died of cancer three years ago, and just before his death, her younger brother died in a car accident.

“That really set my alcoholism off,” she said. “I kind of just stepped out of reality for a while.”

But Phoenix House Recovery wasn’t what Nelson had imagined. She has a background in health care and had been to other treatment centers in the past, and as time went on, she grew suspicious about how the facility was run.

“I started asking questions,” Nelson said. “Like, ‘Where’s the 12-step plan? Why isn’t that in our daily agenda? Why aren’t we learning about triggers, external and internal? Where is our life skills training? Why aren’t we building resumés? Why is there one therapist for 30 patients?’ I asked the clients and staff, and they kicked me out the next day.”

Out on the streets in 100-plus degree weather, Nelson had to find somewhere to go. She looked into other sober living homes but grew concerned when she was offered alcohol and drugs at one of them. She didn’t know who she could trust.

“I was scared,” she said. “I’m thousands of miles away from my family and my home. I was freaking out. I was hysterical.”

While Nelson ultimately made it home to the Blackfeet Reservation, her experience in Arizona is not uncommon.

What happened to her has happened to thousands of other Native Americans in Arizona amid a widespread Medicaid fraud scheme, where treatment centers billed the state thousands of dollars per patient for services that were not actually provided. Indigenous people from Montana, Arizona, New Mexico and South Dakota were recruited to get treatment at these fraudulent facilities, and experts estimate that at least 100 Native Americans from Montana are tangled in the scam.

The scheme defrauded Arizona taxpayers, and at these fraudulent sober living homes, some clients were given drugs and alcohol. Others were told to get on food stamps. And some people seeking treatment were paid to recruit more Native Americans to these facilities. As the fraudulent treatment centers have shuttered amid a government crackdown, Montana tribes and grassroots advocates are scrambling to get their relatives home. But because these facilities changed clients’ state of residency to Arizona for billing purposes, it’s even harder for tribes and families in Montana to locate their loved ones.

What exactly is happening in Arizona?

Arizona officials have called it “a stunning failure of government.”

In a widespread scam, treatment facilities in Arizona billed for nonexistent services, and the money was paid through the Arizona Health Care Cost Containment System (AHCCCS), Arizona’s Medicaid program. The scam targeted Native Americans because a loophole in AHCCCS’s American Indian Health Program allowed individuals to pose as a treatment facility.

Reva Stewart, who launched the campaign #StolenPeopleStolenBenefits to raise awareness of the fraud, said experts have traced the origins of the scam to the pandemic.

“They targeted Native Americans because the American Indian Health Plan would pay for everything they documented,” she explained. “Once these places found out they could get something like $1,700 per day per person, you saw them popping up everywhere. With that money, one home can make $2 million in two weeks. I even saw a YouTube video on how to open a sober living home in 15 minutes.”

The Arizona Mirror reported that AHCCCS was billed $53.5 million under the outpatient behavioral health clinic code in 2019. In 2020, it more than doubled to $132.6 million, and by 2022 it exploded to $668 million.

The FBI, which is investigating the fraud, is seeking to contact victims of the scam. The agency said in some cases, organizers pick up addicts at popular gathering places; sometimes individuals are given alcohol during transport; and clients are told to obtain food stamps during their time in treatment even though their enrollment brings funding to the home. The FBI investigation has resulted in at least 45 indictments by the office of the Arizona Attorney General, and at least $75 million has been seized.

Arizona Gov. Katie Hobbs in May announced, according to The Associated Press, that the homes defrauded the state of hundreds of millions of dollars. AHCCCS has since suspended payments to hundreds of providers in the state.

As these homes have closed, Native American residents are left on the streets of Arizona in temperatures nearing 115 degrees. Some people have been reported missing, and others have turned up dead.

‘I blame them’

Mona Bear Medicine, Blackfeet, said when her 25-year-old son RayDel Calf Looking went to Phoenix for treatment, she had high hopes for him.

Calf Looking completed a longer treatment program, lasting 60 or 90 days, and Bear Medicine said he was doing well. There are many highly regarded treatment facilities in Arizona that have effective programs and competent staff, and plenty of Montana tribal members speak highly of them.

“He sent a selfie over Christmas, and he looked really healthy,” Bear Medicine said of her son. “He looked good. And I could tell he was doing good for himself.”

Bear Medicine said her son started drinking in high school, but she didn’t realize he was doing drugs until about five years ago. Calf Looking was gay, and Bear Medicine said he struggled to come out and faced adversity when people he loved didn’t accept him.

“I think that was the reason he got into drugs,” she said. “He didn’t know how to come out. He was teased for it, and it hurt him. He started doing different drugs, and it got worse and worse, and he got into meth. It was hard for me to realize the extent of it, and I didn’t realize how hard it was going to be on my family.”

Calf Looking completed the long-term program, and then went to a sober-living home in Arizona, called Calm Integrated Healthcare. Bear Medicine said, “That’s when the problems started.”

In February, Bear Medicine hadn’t heard from her son in a while, and she was worried. She and her sister flew down to Arizona and found Calf Looking, who had walked out of the home and appeared to be intoxicated.

“He was disappointed in himself for relapsing,” Bear Medicine recalled.

Bear Medicine took her son back to Calm Integrated Healthcare and almost immediately got a bad feeling about the place. She said her son was clearly intoxicated, and the staff at Calm Integrated said it was fine for him to stay with Bear Medicine at her motel for a few days.

“It was so shady,” Bear Medicine said. “When she said RayDel could stay with us, I asked, ‘What does he need to do? Does he need to go to class?’ And she just said, ‘No, he doesn’t need to do anything.’ When I drove away, I said to RayDel, ‘I’m so confused. I thought sober living was sober.’ And he said, ‘They don’t care as long as they get your money.’”

When Calf Looking stayed with Bear Medicine at the motel, he kept drinking, and after Bear Medicine left, she knew he was still drinking, even though he’d returned to the sober-living home.

In late March, Calf Looking’s cousin, Vandree Old Person, was found dead on the Blackfeet Reservation, and Calf Looking, who was supposed to fly home to be a pallbearer, was taking the death hard. Again, Bear Medicine didn’t hear from him, and again, she was worried.

One day in April, Bear Medicine got a call from a detective.

“When she called, I thought, ‘What did he do now?’” Bear Medicine recalled. “I said, ‘Is he in jail? Is he hurt?’ And she said, ‘No.’ Then she asked me, ‘Is anyone with you?’ and that’s when it started clicking. I said, ‘Oh my God. Is he dead?’ And she said, ‘Yes.’”

The detective told Bear Medicine that her son broke into a house while intoxicated and the homeowner, fearing for his life, shot Calf Looking as he walked up the stairs of his home. Bear Medicine said her son was shot in the back, which she finds incongruous with the detective’s recounting. And she still hasn’t received an autopsy. She was told the FBI is investigating her son’s case, but months later, she still hasn’t heard from the federal agency.

Calm Integrated Healthcare has told Bear Medicine that her son walked out of their facility and was not under their care at the time he was killed, but Bear Medicine maintains that the sober-living home had a part in his death.

“I do think the center was responsible for his death,” she said. “They took the money but still let him drink. He was really trying. He really did try, but it was so easy for him to have a free place to stay that allowed him to drink. I blame them. I really blame them.”

AHCCCS payments to Calm Integrated Healthcare were suspended on May 15 — about a month after Calf Looking was killed.

‘It’s systemic’

Just as with Autumn Nelson, Journey to Recovery in Browning connected Josh Racine to a treatment center in Arizona. A spokesperson for Journey to Recovery was not available for comment.

Racine, Blackfeet, flew out to Sunrise Native Recovery, an alcohol and drug treatment center in Scottsdale, in March. About a month later, he was on the streets.

Laura McGee, Racine’s sister, didn’t know where he was or what happened, but she was determined to find him. She called Sunrise Native Recovery, but they were no help. She called the hospitals in the area, but no luck there, either. Racine would occasionally ask her to send him food at the treatment center — something McGee thought was odd — so she scoured previous food orders to try and nail down a timeline of his disappearance. She scrutinized past texts with her brother to pinpoint a location, but her efforts felt futile.

“I was panicking because I knew what had happened to RayDel,” she said. “It was a feeling I can’t even describe. We lost our mother suddenly, and seven months later, our stepdad, who primarily raised Josh, died. And then our grandmother died, and our first cousin died of an overdose. So Josh is already an addict and now he’s out on the streets dealing with sudden death.”

As McGee did more research, she learned about the hundreds of other sober-living homes in Arizona that had been shut down. It became clear that the problem was bigger than just her and her brother, so she approached the Blackfeet Tribal Business Council.

“I told council, ‘I need help,’” she recalled. “’You sent him there through a program on this reservation. I need help getting him back.’”

The council ultimately paid for a few of McGee’s family members to fly to Arizona, and they successfully brought Racine home, but McGee’s work was not done. Upon her brother’s return, she began to piece together the broken system.

Through conversations with her brother, McGee said she learned that Sunrise charged AHCCCS at least $117,000 in one month for services related to Racine — services that Racine himself said he did not receive.

“That was for one month for one person,” McGee said. “So imagine doing that for 20 or 80 people in a facility. It adds up.”

Racine told McGee that the centers would give clients $50 a week to live on, and he was reportedly told by Sunrise that if he recruited other Native Americans, they would reward him with $100.

“It’s systemic,” McGee said. “There weren’t protocols, and people were being taken advantage of.”

McGee said people struggling with addiction are a particularly vulnerable population, which worked to the scheme’s advantage.

“These are addicts who have lost the trust of their families,” she said. “So when they say, ‘This treatment center isn’t good. They’re putting me out on the street,’ families weren’t believing them. These people knew that and used it against them.”

That’s exactly what happened to Wendy Bremner. Her daughter Brooke Running Crane, Blackfeet, also went to Sunrise, and Running Crane was also suspicious of the facility. She told her mother she wasn’t comfortable at Sunrise and was scared to be there. But Bremner didn’t know what to do.

“I didn’t want to be an enabler,” she said. “I don’t know if what she’s telling me is true. I don’t want to interfere with treatment.”

Later, Running Crane’s anxiety about Sunrise rose to a breaking point, and she was hospitalized for a panic attack. Sunrise told Bremner that her daughter could not return to the facility, and as far as Bremner could tell, her daughter was going to be discharged from the hospital on to the streets.

Bremner called Sunrise over and over again until they finally agreed to help transfer Running Crane to another facility. Running Crane’s new facility is a good one, but Bremner said she doesn’t know what would’ve happened to her daughter if she hadn’t intervened.

“It was really scary,” she said. “She didn’t have anywhere to go, and I was just calling people saying, ‘You can’t just throw my daughter out.’”

Bremner said her daughter ended up at Sunrise because she’d heard of several people in Browning who’d gone there. And when Running Crane expressed that she wanted to receive treatment, Bremner said the treatment facilities in Arizona “felt like a miracle.”

“Families are desperate to get their people help when they say, ‘I want to go to treatment,’” she said. “It’s very rare, so at that moment, you really want to get them in somewhere while they’re ready to go. It’s so hard to get treatment here, and sending her far away is scary, but we wanted her to get help.”

AHCCCS payments to Sunrise Native Wellness were suspended on July 21 — almost two months after Racine went missing and five months after Running Crane’s panic attack.

Tribes take action

After the Blackfeet Council helped get Racine home, it quickly became clear that its work wasn’t done.

As McGee became more vocal on Facebook, more and more families reached out saying their loved ones were missing or stuck at treatment centers in Arizona. McGee continued to present her findings to the tribal government, and eventually, the council came out with a formalized plan of action.

Councilman Lyle Rutherford directed facilities on the reservation, including Journey to Recovery, not to send clients to treatment centers in Arizona. The tribe has worked with McGee and other advocates to bring at least 10 members home. And on Tuesday, the council issued a public health state of emergency “for Blackfeet tribal members affected by the humanitarian crisis arising from shuttered fraudulent behavioral health treatment facilities in Arizona.”

The council on Thursday instituted a ban prohibiting the solicitation of individuals on the reservation to attend fraudulent treatment facilities in Arizona and established civil penalties for individuals or entities that violate the ban at $5,000 for the first offense, $10,000 for the second offense and permanent expulsion from the reservation on the third offense.

The council also pledged to continue to help members who were displaced and said it created a task force to identify displaced individuals.

Councilwoman Shelly Hall said the emergency declaration helps bring awareness to the crisis and could allow the tribe to allocate more money toward its resolution.

“I believe there are about eight or 10 more Blackfeet down there,” Hall said. “This is important because these are our members. If they’re in any kind of trouble, we want to help them. We’ve heard horror stories of people who are on the streets in this heat.”

McGee said she also urged Gov. Greg Gianforte’s office to issue a public service announcement on the matter but was told that his office needed more information on the subject. She also reached out to members of Montana’s congressional delegation, and Sen. Jon Tester sent a letter to the Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services, urging the group to “immediately investigate this matter further and provide a detailed report of their findings.”

The Billings Area Indian Health Service has asked Montana tribes to let the agency know how many citizens have been impacted, and other tribes in Montana have also taken action.

Josie Fisher, Northern Cheyenne, was at a different treatment facility in Arizona and didn’t feel safe. She said a staff member made inappropriate sexual comments to her, and she wrote on Facebook that she wanted to leave.

Fisher got connected with advocates through Facebook, and the Northern Cheyenne Tribe paid for her plane ticket home.

“I’m so thankful to be home,” she said. “I’m at peace now. When I was there, I was just in survival mode.”

Northern Cheyenne Councilwoman Melissa Lonebear said as of Aug. 1, the tribe had helped three members get home from Arizona and added that the council is working with the tribal health department to develop a plan to get more people home.

She said part of the issue is that there is no treatment center on the Northern Cheyenne Reservation.

“The way the system is set up is if someone hits rock bottom and they want treatment, they will do an assessment at the Northern Cheyenne Recovery Center and then get referred to an outpatient 10-day program,” she said. “After 10 days, there’s a chance a bed will open in Billings or Butte, but that person may have to just return home. And because we don’t have sober living homes here, people come back and return to the same environment.”

Lonebear is hopeful that the tribe will be able to help people return home from Arizona, but acknowledged the council will have to overcome significant barriers in doing so. To be eligible for AHCCCS, treatment centers had clients change their residency address to Arizona, so it’s hard for tribal councils in Montana to know how many of their members are there. And tribes have noted that even when someone returns home, it can take time to change their residency back to Montana and re-enroll them in Medicaid.

“I just posted on Facebook asking, ‘How many Cheyenne members do we have in Arizona?’” Lonebear said. “I’m getting names from families, and it’s hard. It’s hard to reach people because there’s no way to communicate if that person doesn’t have a phone. This is a lot bigger than we know.”

Fisher’s boyfriend was at the same facility in Arizona, but it wasn’t as easy for him to get home. Jacinto Brien is Crow, and he tried reaching out to his tribe, just as Fisher had. But he had no luck.

“I tried reaching my tribe on the phone, but I couldn’t get ahold of anyone,” he said. “And because I’m Crow, the Northern Cheyenne Tribe couldn’t help.”

Reva Stewart, of the #StolenPeopleStolenBenefits campaign, ultimately fundraised to help get Brien home. Her GoFundMe has raised more than $8,000 to help Native Americans caught in the scam.

“I’m really grateful,” Brien said of Stewart’s efforts. “I’d just say, for any tribe that’s willing to help, please answer your phones. People need your help. This is important.”

Resources

If you or a loved one is at an Arizona treatment center or was at an Arizona treatment center and wants to come home, here are some resources:

- Call your tribe. See if they can help bring you or a loved one home.

- The Billings Area Indian Health Service is asking each tribe to let the agency know how many members have been impacted. Send relevant information to Jennifer.Lamere@ihs.gov and Steven.Williamson2@ihs.gov or call 406-247-7248.

- For an updated list on which Arizona treatment centers have been suspended, visit azahcccs.gov/Fraud/Providers/actions.html.

- To either verify or report an existing treatment center, visit verifyandreport.org.

- If you suspect Medicaid fraud or a health violation, call the Montana Department of Public Health and Human Services’ fraud hotline at 800-201-6308.

- If you would like to file a report to add to the ongoing FBI investigation into Arizona treatment centers, visit forms.fbi.gov/phoenixgrouphomes.

- Advocates Reva Stewart and Laura McGee can be reached on Facebook.

This article was first published in the Missoulian.

The post Sober living fraud scheme targeted Montana tribal citizens appeared first on Buffalo’s Fire.