Tribe asked to allow search for civil rights activist at Wounded Knee

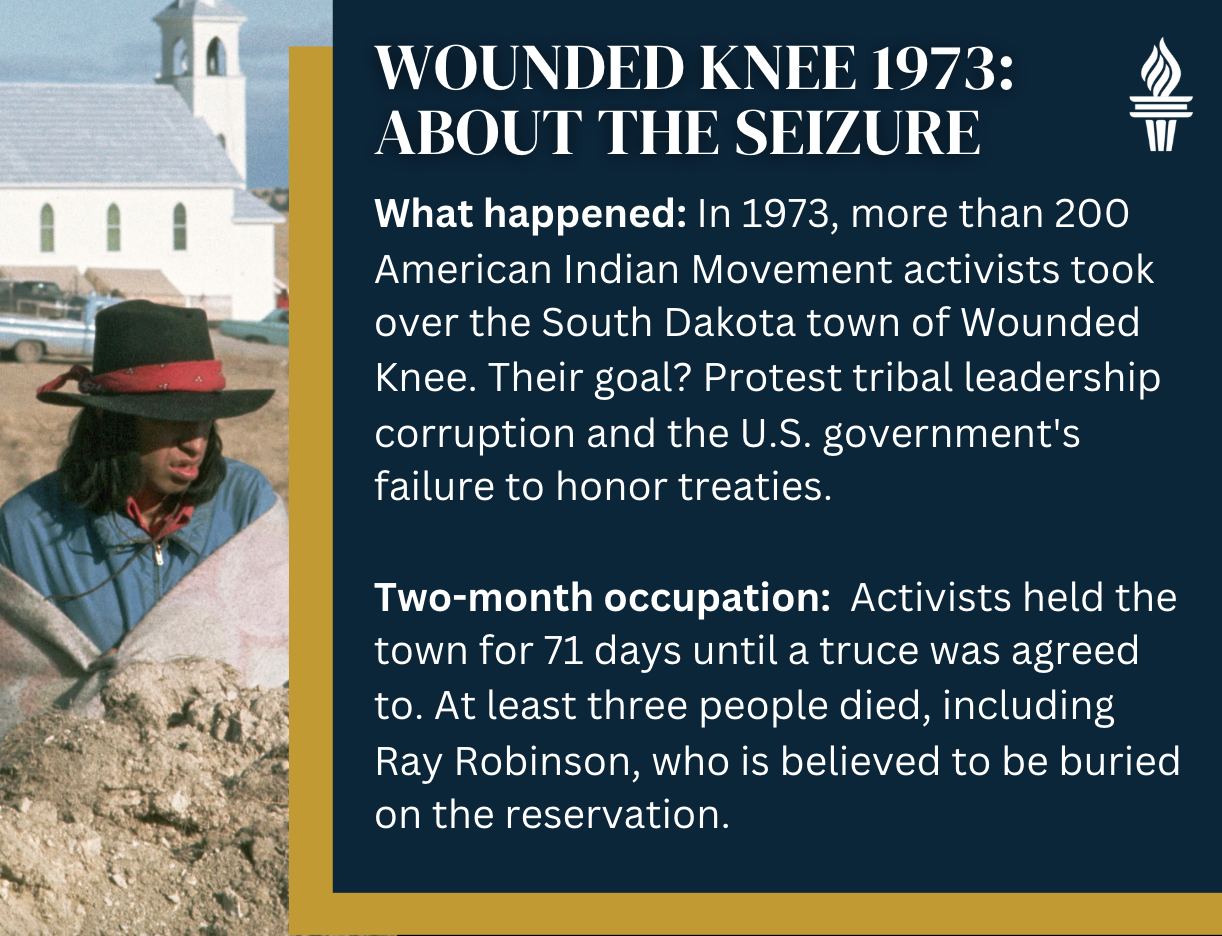

The Oglala Sioux Tribal Council will be asked to approve a search for the remains of a Black civil rights activist who disappeared during the 1973 Wounded Knee standoff. He is likely buried on the Pine Ridge Indian Reservation.

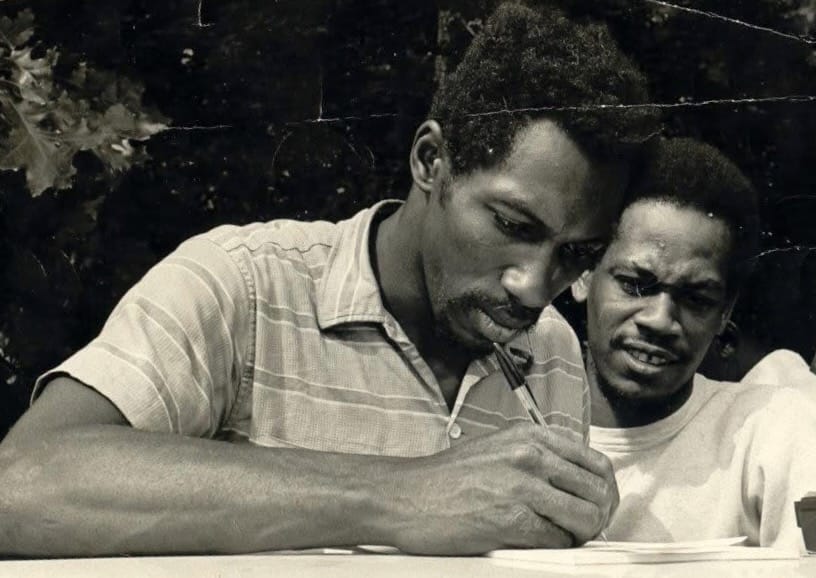

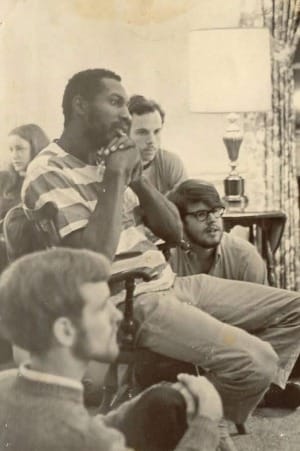

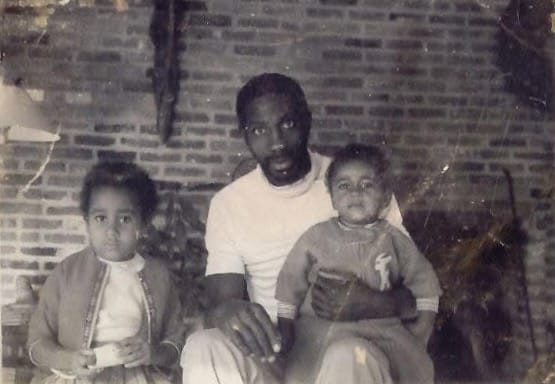

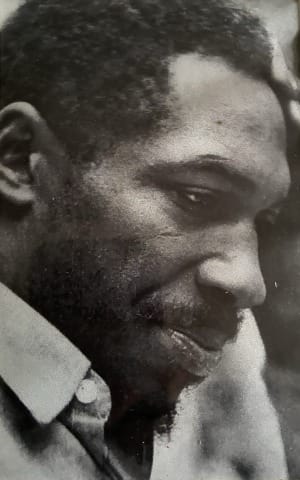

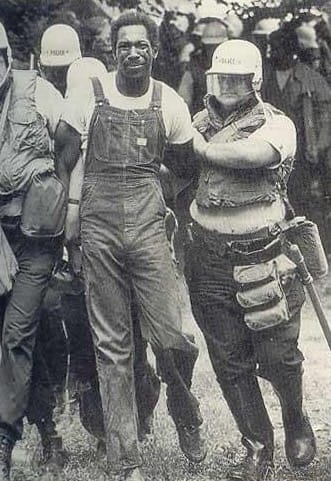

Perry Ray Robinson Jr. was 35 years old when he left his home in Bogue Chitto, Alabama, in April 1973 to answer a call for help from the American Indian Movement. For 71 days, AIM members and supporters occupied the village and exchanged gunfire with federal agents gathered around its perimeter. Robinson never returned, was later declared dead without his body being found, and no one was ever charged.

His name came to light after two men were indicted in 2003 on charges they killed Canadian Annie Mae Aquash in December 1975 in South Dakota’s badlands.

Arlo Looking Cloud was arrested in Denver. A federal jury in Rapid City convicted him in 2004 of murder. He was sentenced to life in federal prison, but that was later reduced to 20 years because of his cooperation and acceptance of responsibility. He was released in 2019.

The other man, John Graham, fought extradition from his native Canada. A state jury in Rapid City convicted him of murder in 2010 and he is serving a life prison sentence at the South Dakota State Penitentiary in Sioux Falls.

Hulu documentary about Aquash

Justin Baker, 40, who lives in Mission on South Dakota’s Rosebud Indian Reservation, started the latest effort to search for Robinson’s body.

He has been following the Aquash and Robinson cases since Looking Cloud and Graham were indicted. That included reading media accounts and documents released as part of a Freedom of Information Act request. Baker said he also spent considerable time with Leonard Crow Dog, a Sicangu Lakota medicine man and AIM’s spiritual leader who died in 2021.

Baker said he was prompted to action after watching a recent documentary about Aquash on the streaming service Hulu entitled “Vow of Silence: The Assassination of Annie Mae.”

Witnesses testified that Aquash, who also responded to AIM’s request for help and rose to prominence in the organization, was killed because she was suspected of being an informant.

“I started thinking, ‘Why can’t they do something for this man, Ray Robinson?'” Baker said.

He called Paul DeMain of Hayward, Wisconsin, the former editor of the News From Indian Country newspaper who extensively investigated the Aquash and Robinson cases.

Among the people DeMain put Baker in touch with was Robinson’s widow, Cheryl Buswell-Robinson, and their son, Deeter Robinson.

“I asked Deeter, I said, ‘What would you like me to tell people?’ And he said what it was like growing up without a dad, not having somebody at my sporting events, not having a man’s guidance, not having a father to lean on, and it caused a lot of hardships in my life,” Baker said of the conversation.

“This is somebody’s family that was destroyed and is still hurting 52 years later, and there are still people remaining silent.”

Concerns about 1890 massacre site

DeMain had already done extensive work trying to identify Robinson’s likely resting place. Baker took up the cause using tribal channels.

“I wanted to create a grassroots effort because I think everything else has been tried already,” he said.

Baker presented a resolution to and received unanimous support for it in May from the Sicangu Lakota Treaty Council. That group in the Great Sioux Nation advocates for Native treaty rights and inherent sovereignty. The document’s purpose was to start building support for a culturally sensitive search for Robinson’s remains on the Pine Ridge reservation.

Baker then went to the Oglala Sioux Tribe’s land committee on Pine Ridge, which rejected the request for a search, saying it could unearth remains or artifacts from the 1890 Wounded Knee massacre.

Baker said the search would only involve a cadaver dog or ground-penetrating radar that would not disrupt the land. And the area already has been disturbed, he said.

“Wherever Ray is laying was already disturbed through the form of buildings, construction within the downtown Wounded Knee area, or it was disturbed in 1973 from digging bunkers,” Baker said.

Baker has drawn up a resolution he plans to present to the Oglala Sioux Tribal Council, which includes the Sicangu Lakota Treaty Council resolution and letters of support from elders, descendants of the 1890 massacre and others.

The document, viewed by South Dakota News Watch, calls for all Lakota tribes, in collaboration with Buswell-Robinson and cultural experts, to create a working group to oversee a non-invasive search for the remains of Robinson. The effort would include historic preservation officers, spiritual leaders and elders, the Robinson family, Indigenous archaeologists and forensic scientists and independent advisers.

“This resolution does not seek the removal or exhumation of any remains but seeks only to locate, document and honor the possible resting place of Perry Ray Robinson Jr.,” it states.

The document also calls for transparency and respect of those who died in 1890 and might have been killed on the site in 1973.

“We’re asking to search the ground that already has been disturbed and is a long way from the burial of the 1890 massacre victims,” Buswell-Robinson said.

Tribal leaders did not respond to a request for comment.

Widow hopes for Robinson’s return

Besides a son, who has children, the Robinsons have two adult daughters in Detroit, Desiree Marks and Tamara Fant, who have their own children and grandchildren.

“I’m 80 and doing fine. I’d like to get Ray back here before I’m dead,” Buswell-Robinson said. “I’m excited about it because Justin (Baker) is so excited.

“He’s been wonderful to follow and has a strategy.”

Buswell-Robinson said that because she’s in Detroit, she doesn’t have the connections or know the local structures or politics like Baker does.

Based on her recollections and letters she wrote in the years after her husband’s disappearance, she believes he probably was killed because he naively thought he could turn an unorganized situation into a focused demonstration.

His nonviolent approach probably was not well received at what was a violent situation, Buswell-Robinson said. And it’s possible AIM members suspected he was a federal informant, which he was not, she said.

FBI documents include references to fresh graves

Two American Indians were confirmed to have died during the 1973 siege, and rumors of other deaths persist. FBI documents that are now public suggest the possibility of other people buried at Wounded Knee during the occupation.

A May 1973 memo says the FBI talked to a man who reported grave sites just outside of Wounded Knee. Another, a few days later, states that an Interior Department official “observed several fresh graves” at Wounded Knee. One of the graves belonged to one of the two Native Americans killed, the memo states.

There’s no mention of Ray Robinson in the FBI correspondence, but two documents reveal the presence of two Black people toward the end of the standoff.

A May 5, 1973, transcript of an interview with a man who claimed to be at Wounded Knee the week prior stated “he heard that one black man and one black woman had recently arrived.”

A May 21, 1973, FBI memo reported that a Native woman who left the village a month earlier counted 200 Indians, 11 whites and two Blacks. Buswell-Robinson said those two were most likely Ray Robinson and a woman from Alabama who went with him.

She returned after the standoff. He didn’t.

This story was produced by South Dakota News Watch, an independent, nonprofit organization. Read more stories and donate at sdnewswatch.org and sign up for an email to get stories when they’re published. Contact Carson Walker at carson.walker@sdnewswatch.org.