Frustrated with used needles littering city streets, some local officials have called for renewed restrictions on syringe service programs, which they say contribute to the recent rise in needle waste.

But harm reduction experts say the needle waste — and high rates of infectious disease among injection drug users in Maine — is evidence that these programs should be expanded, not restricted.

Syringe service programs offer supplies, including sterile needles, naloxone and fentanyl, and xylazine test strips, to people who inject drugs, with the goal of reducing overdose deaths and disease outbreaks.

The programs also help connect people to services and serve as a critical “touch point for people who are otherwise marginalized from the health care system,” said Dr. Robin Pollini, an epidemiologist and harm reduction expert at West Virginia University.

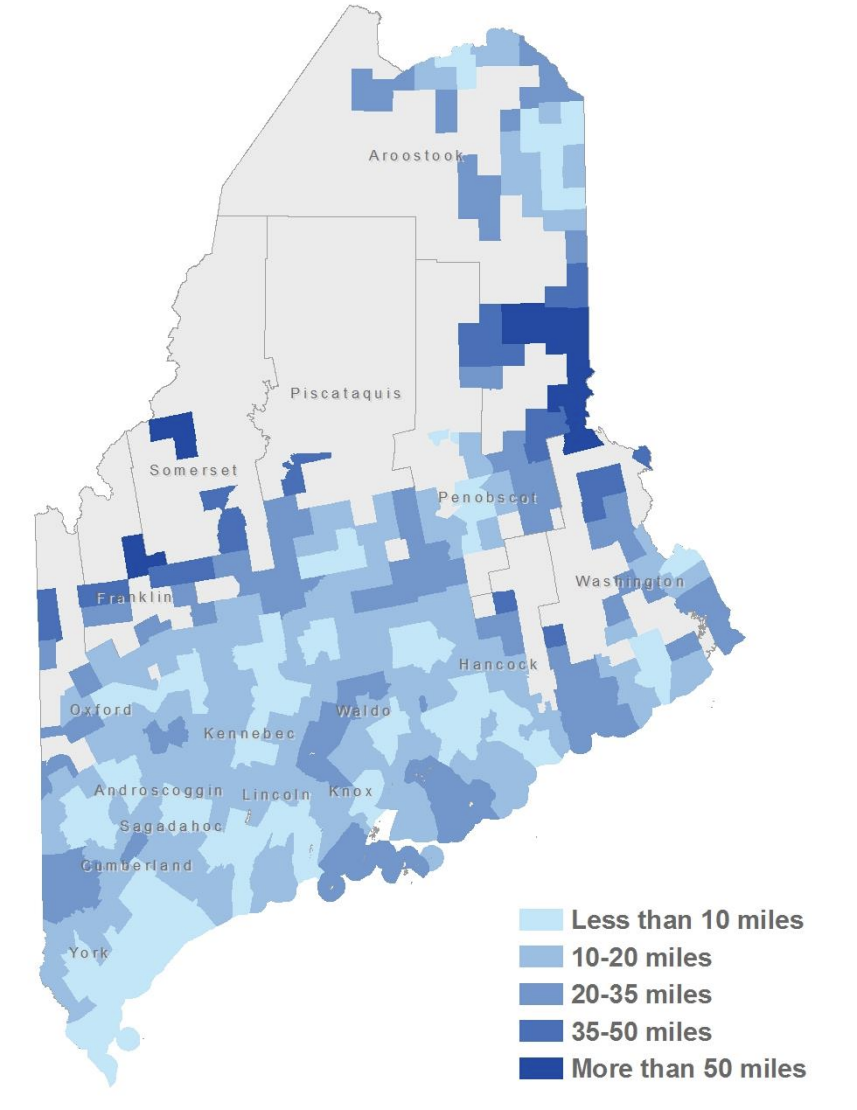

Maine’s first syringe service program, The Exchange, operated by Portland’s public health department, opened in 1998 and remains the only municipally run program in the state. The Maine Center for Disease Control and Prevention certifies the programs and the sites where they can operate. Although program operators must provide notice of their intent to file for certification, municipalities do not have a role in the certification process, which has led to complaints from some city leaders that programs pop up in their towns with little to no consultation.

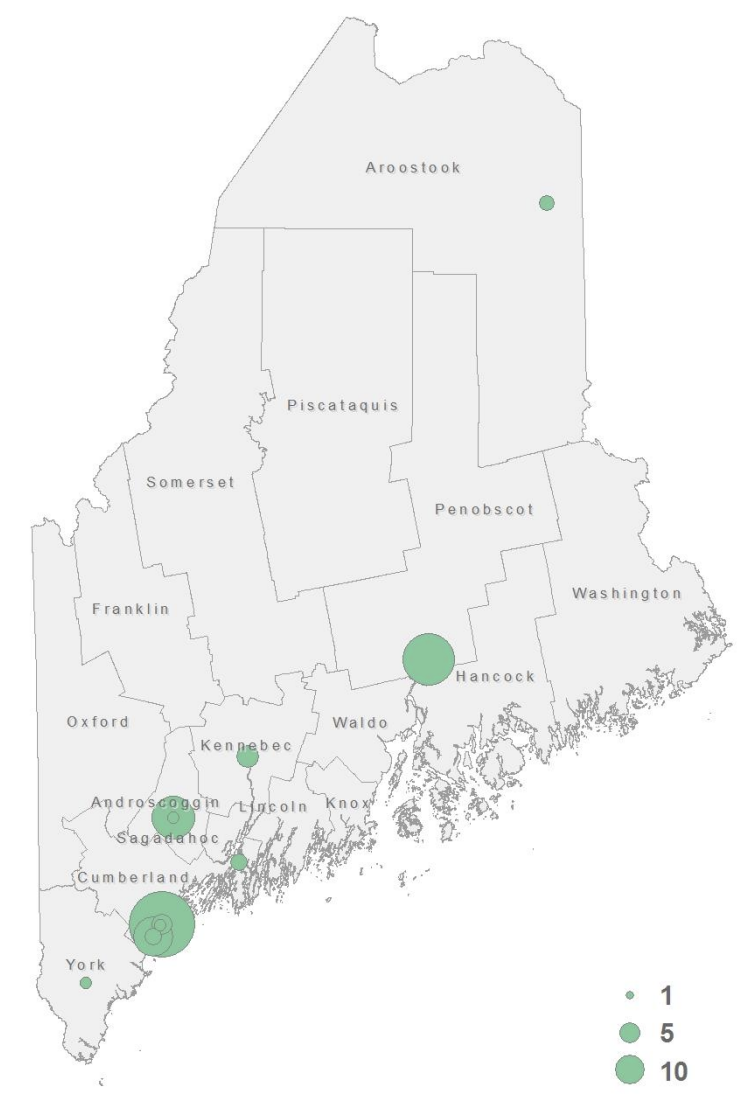

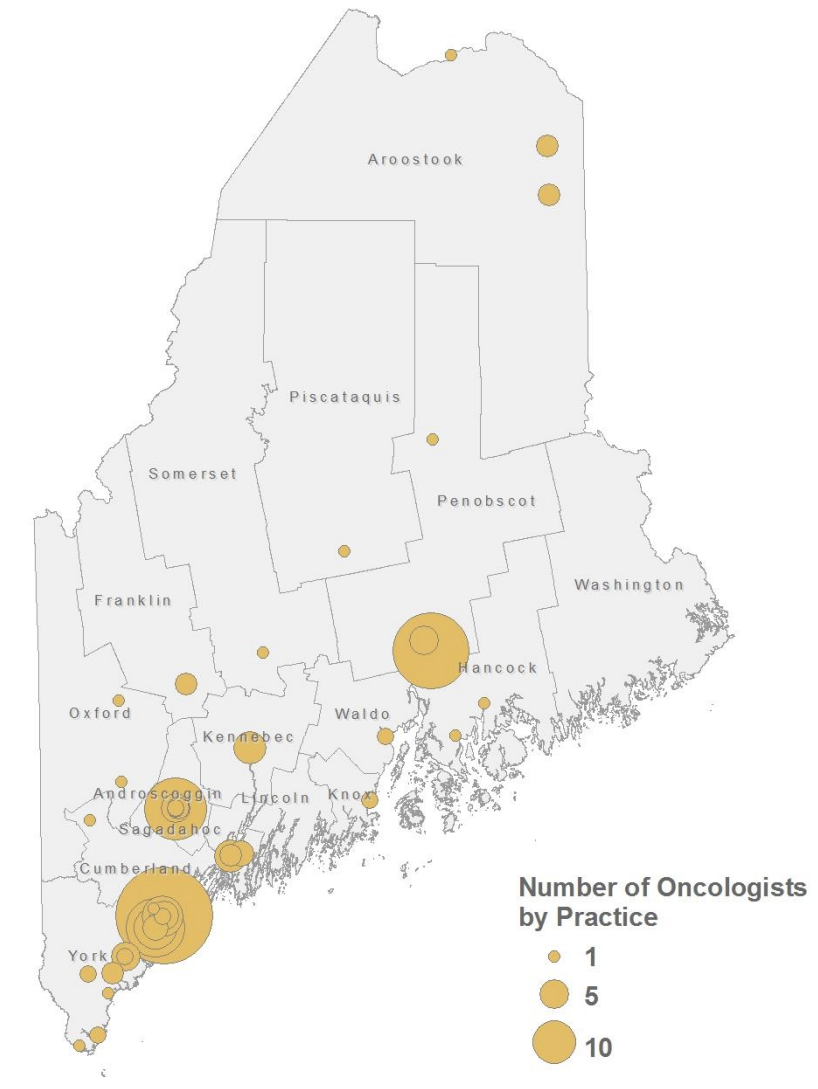

As of last year, 13 of the 32 certified programs were in operation statewide, according to the Maine CDC’s latest annual report. While some programs have been in operation for over a decade, the majority — eight of the 13 that are active — opened within the past four years.

For more than two decades, state rules limited programs to a 1-for-1 exchange, meaning they could only provide one sterile syringe for every used one a person brought in. In late March 2020, Gov. Janet Mills suspended that rule and made it so that programs could adjust their hours without state approval and operate anywhere within the county in which they were certified. The rule change also allowed them to mail supplies.

Mills’ executive order acknowledged that the public health emergency posed “substantial barriers” for clients to access syringe service programs and cited a desire to maintain a continuity of services during the COVID-19 pandemic.

The change was hailed by the American Medical Association, which urged other states to adopt similar policies. At the time Maine had 11 certified programs operating in 10 cities — Portland, Ellsworth, Bangor, Machias, Belfast, Calais, Augusta, Waterville, Sanford and Lewiston. Most programs quickly relaxed their rules. Maine Access Points, which at the time operated programs in Sanford and Calais, started a mail-order program. But Portland doubled down on the 1-for-1 policy and refused to loosen its rules for more than a year.

In September 2022, shortly after Mills’ order expired, the Maine Department of Health and Human Services adopted a 1-for-100 rule that allows programs to distribute up to 100 more needles than a person turns in. If someone turns in 20 used needles, for example, they can get 120 sterile needles. If someone doesn’t have any used needles, they can still get up to 100 sterile needles.

But in the past few weeks Portland Mayor Mark Dion and Sanford city manager Steve Buck called for a return to the 1-for-1 rule.

In a Sept. 12 op-ed in the Portland Press Herald, Dion said “needle waste is a public safety hazard of our making” and that he would introduce a resolution to the city council next month to go back to 1-for-1. (Dion previously supported loosening restrictions on The Exchange in 2021.)

Over the past decade, enrollment in a syringe service program has almost doubled. Last year nearly 8,400 people were enrolled in a program, a 25 percent increase from the previous year. Accompanying this boom was a dramatic increase in the volume of syringes that the programs distribute and collect every year.

In 2023, the 13 programs distributed nearly 3.7 million sterile syringes — four times the amount they distributed in 2019 and seven times the 2013 amount. They collected about 3.2 million used syringes, or 86 percent of what they distributed. Before the pandemic and the rule change, programs typically collected the same number of syringes they gave out every year, or more.

Dion and Buck said the high volume of syringes that programs distributed and the discrepancy between the number collected explains the uptick in needle waste on city streets.

Portland’s two programs, The Exchange and commonspace, distributed nearly 1.4 million syringes last year. That was more than double the next-highest total distributed in a single city, though the number of people enrolled in either Portland program accounts for 43 percent of the enrollees statewide.

Together, The Exchange and commonplace collected about 294,000 fewer syringes than they gave out.

Residents have complained about improperly discarded syringes in public spaces for years, even before the city loosened its 1-for-1 rule. At a March 2021 health and human services committee workshop, Marie L. Gray wrote, “As a longtime resident of the Parkside neighborhood and an avid walker, the issue of randomly discarded needles is a major concern. Unfortunately it is almost impossible to take a walk through the neighborhood and not see several discarded needles.”

At a West End Neighborhood Association meeting earlier this month, Rich Bianculli, echoing complaints from other residents, said the situation is, “kind of a nightmare,” the Press Herald reported.

Buck, the Sanford manager, in a memo to the city council earlier this month, estimated that after the city sweeped a homeless encampment in mid-June, workers collected about 14,700 used syringes. The encampment, which had been there for about a year, was located next to the syringe service program operated by Maine Access Points.

Last year, MAP distributed 460,720 sterile syringes and collected 441,998 — a difference of roughly 20,000. Buck claimed most of those missing needles were found in the encampment clean-up.

He attached several photos taken in August that showed needles strewn about at public parks around the city.

“The City recognizes a public health crisis exists due to the extraordinary number of inappropriately discarded contaminated needs that puts people at risk of becoming infected by the very pathogens the program seeks to reduce,” Buck wrote.

But some advocates say the problem shows there’s not enough access to syringe service programs.

“To me, what that says is there is not enough access,” to programs, where people can hand in their used syringes and learn more about safe disposal techniques, said Zoe Brokos, Church of Safe Injection’s executive director.

“It doesn’t mean reduce access to syringe service programs or cut off somebody’s safe supply of sterile equipment because the only thing that does is increase disease transmission.”

A 2019 study found that improperly disposed needles in publicly accessible areas of Miami decreased by 49 percent after a syringe service program was established there — in part, researchers suggested, because people injecting drugs had a safe place to dispose of used needles. Several other studies linked syringe service programs to less needle litter and a higher inclination to practice safe disposal among the people who use the programs.

According to the U.S. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, new users enrolling in these programs are also far more likely to enter treatment and stop using drugs altogether compared to those who don’t enroll. Last year, syringe service programs in Maine made more than 26,100 referrals to various services, such as primary care and housing assistance, more than double the amount in 2022.

Gregg Gonsalves, a Yale University epidemiologist and public health policy expert, suggested approaching needle waste as its own issue, rather than as a symptom of syringe service programs.

“The cost of instituting a clean-up program in these jurisdictions, in these cities and these towns, is far, far less expensive than paying for the lifetime medical costs for somebody who is HIV positive or HCV positive,” he said. “The economic argument is just unequivocal.”

“The point is that (needle waste) is a resolvable issue. We can resolve it in a pretty simple way by enhancing sanitation efforts.”

The executive directors of Maine Access Points, Church of Safe Injection and Wabanaki Public Health and Wellness all told The Monitor that their staff regularly does syringe clean-up in their communities.

There are no sharps containers — metal boxes where people can drop used syringes — in Sanford, said Anna McDonnell, MAP’s co-founder and interim executive director. That’s why MAP is installing its own sharps container that is accessible 24/7.

Closing or restricting syringe service programs only means more infections at a time when infectious diseases, particularly among people who inject drugs, is at an all-time high in Maine and around the nation, advocates say. Maine had the highest rates of new hepatitis A and C cases in the country in 2022, the latest year federal data is available. It had the third-highest rate of new hepatitis B cases, according to the U.S. CDC.

There is an historic cluster of HIV infections in Penobscot County that was first identified last October. Two of the three initial people diagnosed in the cluster reported they were unhoused and shared or reused equipment to inject drugs. As of Sept. 21, a total of 13 people were diagnosed with HIV; all of them were also diagnosed with hepatitis C and all of them reported recent injection drug use. Eleven were currently or recently unhoused.

“I think one of the things that really gets confused is the conversation around syringe litter. It’s really a conversation about housing, about housing access and about supporting people who are unhoused,” McDonnell said.

“We serve a lot of folks who are housed and who don’t have an issue with safely disposing of their syringes. And so the conversation really shouldn’t be about the efficacy of the syringe service programs or how well we’re able to do our job. It’s really about the conversation around people who are homeless, being displaced and not having anywhere to kind of have their belongings or deal with their waste safely.”

Over the past five years, Penobscot County averaged two new HIV diagnoses per year, one of which was a person who uses drugs, according to the Maine CDC.

As the number of cases grew earlier this year, a third syringe service program in Bangor, Needlepoint Sanctuary, was certified to operate up to three sites in the city, as well as one each in Waterville and Milo, according to the executive director, Willie Hurley.

But the city has repeatedly rejected the organization’s proposed locations, most close to homeless encampments, or in or near public parks. They have yet to reach a solution and the program is limited to doing mobile outreach within the city’s homeless encampments, which it has already been doing for years, Hurley said.

“The last thing you want to do is restrict” syringe service programs while in the midst of an HIV outbreak, said Pollini, the West Virginia epidemiologist. Limiting the number of syringes a program can distribute is “virtually ensuring that people are going to share or reuse syringes, and that doesn’t serve any of us.”

Although more and more people visit Maine programs, the number a person typically makes has stayed roughly the same for 15 years, at three to four times per year.

In 2023, enrollees in a Maine program exchanged an average of 102 used needles for 118 sterile ones at each visit. Ten years ago, people exchanged an average of 38 needles.

Dion, in his op-ed, suggested that providing 100 needles simply provides multiple “changes for addicts to taunt the finality of their own lives.”

But experts — including from the U.S. CDC — say a needs-based program is best practice, especially since fentanyl has proliferated the state’s drug supply.

“Fentanyl has a very short half-life and people are injecting a hell of a lot more than they ever used to,” said Whitney Parrish-Perry, MAP’s former operations director. One person could easily go through five to 10 needles in one day.

“People assume that if you don’t give people who inject syringes, they won’t inject drugs. And that’s patently false. People are going to inject whether you give them sterile syringes or not,” Pollini said.

“The question is not, will they inject or not inject? The question is, will they inject with a sterile syringe or a used syringe?”

Providing people with sterile syringes has not been shown to increase overdose risk. And each time a syringe is reused or shared, the risk of acquiring blood-borne infections increases, as does the potential to develop serious and life-threatening bacterial infections, Pollini added. Xylazine, an animal tranquilizer that has been growing in prevalence in Maine’s drug supply, is also known to cause necrotic wounds, which can lead to infections.

Advocates say these programs also help by reducing health care costs: nationwide, hospitalizations and lifetime medical costs for infections associated with injection drug use cost hundreds of millions of dollars annually.

Those deaths — “where someone sits in the hospital for three months and slowly dies of sepsis,” Brokos said, “those get completely forgotten in these conversations.”