Aroostook power corridor faces opposition from rural landowners

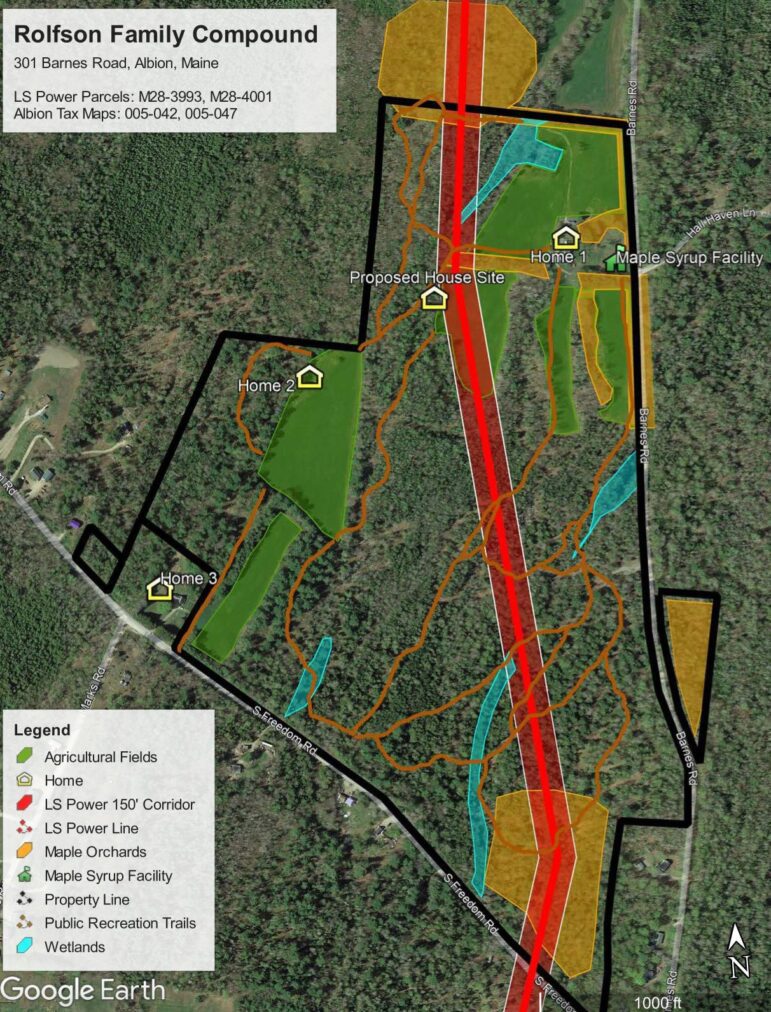

ALBION — Over 50 years, Eric and Rebecca Rolfson have created a rural oasis in this central Maine farming community. On 123 acres, they have hand-built a log cabin and renovated a 200- year-old family farmhouse.

They have created a maple syrup business, cultivated hayfields that serve local dairy farmers and cut a community trail system through their woods. This is where they plan to grow old, on land where Eric Rolfson’s parents are buried.

So they were shocked last July when they received a letter from LS Power, a New York City-based power and transmission system developer.

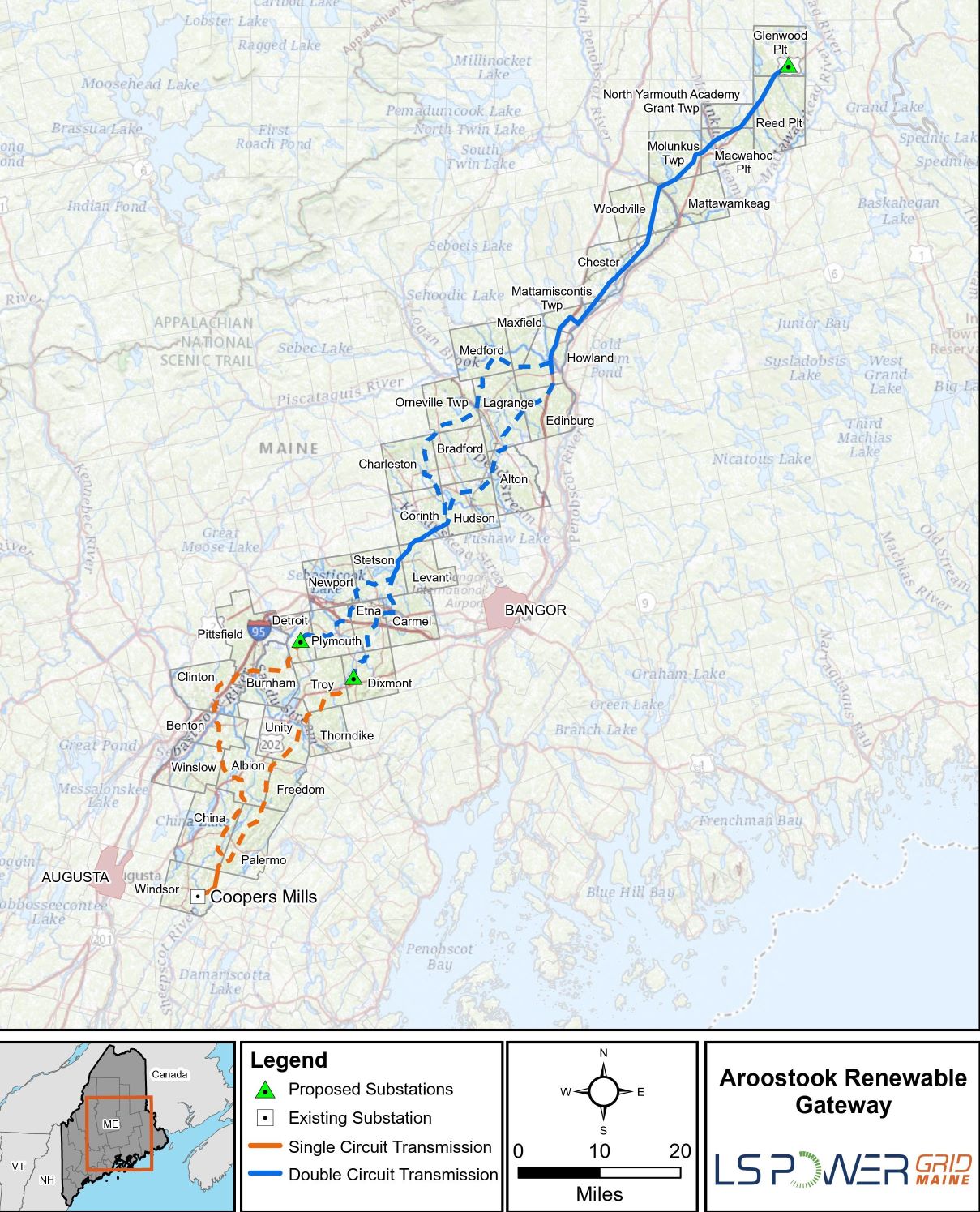

The Rolfsons learned they were among 3,500 or so landowners with property on the potential route of the Aroostook Renewable Gateway, a roughly 140-mile overhead transmission line that would connect the largest wind farm east of the Mississippi River with New England’s electric grid.

A map shows a potential 150-foot wide corridor slicing north-south through the Rolfson’s property.

Standing in the farmhouse’s yard in mid-November, looking up at the wooded ridge that could someday trace the path of transmission lines strung from 110-foot towers, Eric Rolfson expressed his frustration and fear after a lifetime of pouring his heart into the land.

“We love it here,” he said. “We can’t imagine looking up at those towers.”

When it was approved last June by lawmakers and signed by Gov. Janet Mills, the bipartisan legislation enabling the Aroostook Renewable Gateway was hailed as an achievement that would finally unlock northern Maine’s green energy potential while lowering electric rates.

But already the Aroostook line is beginning to feel reminiscent of another controversial corridor — the troubled New England Clean Energy Connect project, the six-year effort by Central Maine Power’s parent company to build an overhead transmission line from Quebec to Lewiston.

After years of court battles, a citizens referendum was overturned in April and work was allowed to resume. Crews are being reassembled to finish the now-estimated $1.5 billion project, the company said, with plans to energize the line in 2025.

Meanwhile the Rolfsons, and neighbors in Albion, Palermo, Freedom, Thorndike and Unity, are organizing in opposition to the Aroostook line.

They have held protest rallies. They set up a Facebook page with 1,000 members and created a citizen group, Preserve Rural Maine. They’ve hired a Portland attorney with experience fighting transmission lines, including NECEC.

Nearly a dozen towns have enacted temporary moratoriums.

This wasn’t supposed to happen.

The 2021 citizens’ initiative aimed at killing NECEC also contained unprecedented language that requires the legislature to approve any new “high-impact electric transmission lines.”

The idea was to provide a check on developers seeking to push projects through communities that opposed them. The Aroostook line was the first test of the new law and, based on the fight brewing here, it’s not working as planned.

Two problems are becoming obvious. First, rank-and-file lawmakers were asked by key legislative leaders to endorse the project before even knowing where the transmission corridor would run. Second, language in an initial 2021 transmission line bill encouraged new lines to be located in existing rights-of-way or corridors “whenever feasible.” But feasible is a broad term, leaving it to developers to assess what’s technically and financially doable.

The prospect of new transmission corridors going through resistive communities has led some lawmakers to take a step back.

Eleven relevant bills were proposed for the upcoming legislative session, ranging from study alternatives to preventing eminent domain takeovers to rescinding approval altogether. None got the initial go-ahead this month from the Legislative Council, the 10-member leadership body that controls the flow of legislation, although one was granted on appeal. The council includes two Aroostook County lawmakers who are key champions of the project: Senate President Troy Jackson, a Democrat, and Senate Minority Leader Trey Stewart, a Republican.

There’s wide agreement that Maine and the region will need more transmission lines to carry clean energy and phase out the fossil fuel generation linked to climate change. But the highly organized opposition against the Aroostook venture is raising a critical question about how Maine is pursuing its interconnection goals.

What lessons have politicians and policy makers learned from the NECEC debacle, or from Northern Pass in New Hampshire, the failed attempt to construct a 192-mile overhead line from Quebec that was killed in 2018 after stiff community opposition?

Northern Pass, NECEC and Aroostook Renewable Gateway have something in common. They were designed to carry high-voltage power over lines strung on tall towers running through wide swaths.

By contrast, a similar-size project now being built from Quebec to New York City, the Champlain Hudson Power Express, plans to run cables underground and underwater in narrow corridors. Another cross-border proposal, Twin States Clean Energy Link, would put some of the line under state roadways.

The Aroostook Gateway is the product of decades-long ambitions to connect Maine’s northernmost county with New England’s electric grid, and boost the local economy by building wind, solar and biomass power plants.

It remains in its early stages, planned to come on line in 2029. LS Power has yet to seek key permits from utility and environmental regulators.

As the process unfurls, two additional questions loom: Will Maine push ahead with an unpopular overhead transmission design that has snarled two similar high-profile projects? With an eye on lessons from Northern Pass and NECEC, is it still possible to bury cables underground?

For its part, LS Power stresses that no routes have been finalized.

The company met in July with residents along proposed route options to hear their concerns. It plans a second round of meetings in early 2024 and expects to adjust the route based on feedback.

The route is subject to change until all permits are in hand, the company said, no sooner than 2026.

The company even explored placing towers along sections of Interstate 95, but that idea was rejected by the Maine Department of Transportation.

One thing not likely to change, according to Doug Mulvey, the company’s vice president for project development, is the alternating current, overhead wires design. LS Power is familiar with underground projects, working on one in San Jose, Calif., Mulvey said.

But burying a high-voltage line that carries the required direct current from Aroostook County to central Maine would cost roughly five times more than the overhead option, he said. That would be a non-starter because a top reason the $2.9 billion project won a competitive bid process at the Public Utilities Commission is it promised to save electric customers money.

“Everyone in the state, everyone we talked to, is extremely concerned about rates,” Mulvey said.

Adding to the complexity, LS Power and the PUC are bogged down in negotiations over details of the power purchase and transmission service agreements. Mulvey told the Portland Press Herald that the impasse was putting the project at risk.

Renewable energy versus ratepayers

The Aroostook Renewable Gateway checks a lot of boxes on the wish list for Maine’s clean energy aspirations.

The line would connect to a 170-turbine wind farm in southern Aroostook County called King Pine, to be built by Boston-based Longroad Energy. The $2 billion project would have a capacity of 1,000 megawatts, producing enough electricity to power 450,000 homes. Other generators, such as solar or biomass, might someday also be able to use the line.

In approving King Pine and the power line last January, the PUC estimated that most Maine residential electricity customers would pay an extra $1 a month — or $1 billion in total — for a 60% share of the project. The rest would be paid by Massachusetts customers as part of that state’s clean energy acquisitions. The actual megawatt-hour cost of electricity hasn’t been made public.

When it was approved by the PUC, the project was hailed by Mills’ energy office as a way to combat the impact of volatile natural gas costs on electricity supply, while creating economic opportunities in northern Maine. Jackson said it would unlock affordable, homegrown renewable energy and create good jobs.

“With today’s vote,” Jackson said at the time, “we are the closest the state has ever been to making the northern Maine transmission line a reality, and unleashing the untapped economic potential and power of Aroostook County.”

All this seemed far away in Albion, roughly 130 miles south of the planned wind project. This is dairy farm country in a state where the industry has been shrinking for decades. But here, 10 dairy farms hang on, evident by the hayfields and pastureland spread across rolling hills.

Driving the country roads, what sticks out most isn’t the cows. It’s the signs. Election season is over but what looks like roadside campaign signs are everywhere. Black-and-white signs read: “Keep LS Power off our land.” Yellow signs with an outline of a transmission tower say, “Stop Gateway Grid,” with the weblink, PreserveRuralMaine.org.

The signs are on the Noyes Family Farm, a third-generation dairy operation with 100 cows that grows corn and hay on 370 acres. Chuck Noyes and his daughter, Holly, were part of a protest at the Albion town office in late July. It was organized to call attention to concerns ranging from loss of farmland to electromagnetic radiation from overhead wires.

In mid-November, Holly Noyes came to the Rolfson farmhouse, with several residents who formed action committees in their communities, to talk about next steps. Over pancakes and the farm’s maple syrup, they discussed a path forward.

“What are our next steps if the legislature isn’t going to listen?” asked Josh Kercsmar of Unity, vice president of the Preserve Rural Maine group. “Where can we turn?”

‘No real input’

This is not what lawmakers had in mind in 2021 when they considered LD 1710. The bill created the Northern Maine Renewable Energy Development Program and directed the PUC to seek proposals for a transmission line that would ship power from green-energy generators in Aroostook County into the New England grid. Jackson, who represents a district in far northern Maine, was the lead sponsor.

But some interest groups that testified on the bill, such as the Maine Farmland Trust, urged lawmakers to remove the “wherever feasible” clause, to “ensure that there is a strong preference for proposals that are collocated with existing utility corridors and roads, and as such, avoid further impacts to important natural and working lands.” No changes were made.

And after the passage in June of LD 924, a follow-up, legislative resolve sponsored by Jackson, Stewart and others to signal specific approval for the Aroostook Gateway, some lawmakers felt the process was being rushed.

“My big concern,” said Rep. Steven Foster, R-Dexter, “is that we’re approving this line, it’s going through 41 communities, but there was no real input during the legislative process before the approval was made.”

Foster, who serves on the legislative committee that handles energy matters, represents towns through which the line could pass.

He proposed a bill for the upcoming session to reconsider the project’s PUC approval. It was rejected by leadership in early November, along with all but one of the proposed remedial measures — a bid from Sen. Chip Curry, D-Waldo, to prevent eminent domain from being used to build the line.

“I think (Senate) President Jackson and others are determined to get this project done,” Foster said. “And I’ll leave it at that.”

Jackson’s perspective, however, is that some lawmakers who oppose wind farms were “piling on” to create obstacles.

After meeting with the Albion-area organizers, Jackson said he’s sympathetic plight and wants LS Power to do its best to mitigate impacts. But he doesn’t see how the lines can be buried, based on the PUC’s bidding criteria.

“That’s not what the PUC asked for in its request for proposals,” Jackson told The Maine Monitor. “They would have to re-bid the whole thing. You’re going to have different costs and ratepayers are going to be impacted.”

But by selecting a project with overhead transmission lines, Maine is ignoring a lesson from both Northern Pass and NECEC, according to Beth Boepple, a Portland attorney who represented opponents in both cases. It’s technically feasible to run high-voltage cables underground along existing corridors or roadways, she said, and that’s what Maine should require.

“It’s one of the lessons we should have learned,” she said. “We don’t need to reinvent the wheel.”

One difference, Boepple said, is opponents have organized early. There’s still time to press the PUC and permitting agencies such as the Department of Environmental Protection to require underground cables. That could avoid long and costly legal battles, she said.

“We’re a long way from going to court,” she said. “There’s a lot that can be done through the permitting process.”

But even at this early stage, the process is fraught with competing tensions, according to Bill Harwood, Maine’s public advocate.

The developer requested and won some assurances before investing millions of dollars. But the legislature had to sign off on a major project without key information.

Customers statewide want lower-cost electricity. Local residents, though, don’t want giant towers and overhead wires on their land.

“Going forward,” Harwood said, “we need to think carefully about whether there’s a better way.”

The story Aroostook power corridor faces opposition from landowners appeared first on The Maine Monitor.

How Florida farm workers are protecting themselves from extreme heat

This story is part of Record High, a Grist series examining extreme heat and its impact on how — and where — we live.

On any given summer day, most of the nation’s farm workers, paid according to their productivity, grind through searing heat to harvest as much as possible before day’s end. Taking a break to cool down, or even a moment to chug water, isn’t an option. The law doesn’t require it, so few farms offer it.

The problem is most acute in the Deep South, where the weather and politics can be equally brutal toward the men and women who pick this country’s food. Yet things are improving as organizers like Leonel Perez take to the fields to tell farm workers, and those who employ them, about the risks of heat exposure and the need to take breaks, drink water, and recognize the signs of heat exhaustion.

“The workers themselves are never in a position where they’ve been expecting something like this,” Perez told Grist through a translator. “If we say, ‘Hey, you have the right to go and take a break when you need one,’ it’s not something that they’re accustomed to hearing or that they necessarily trust right away.”

Perez is an educator with the Fair Food Program, a worker-led human rights campaign that’s been steadily expanding from its base in southern Florida to farms in 10 states, Mexico, Chile, and South Africa. Although founded in 2011 to protect workers from forced labor, sexual harassment, and other abuses, it has of late taken on the urgent role of helping them cope with ever-hotter conditions.

It is increasingly vital work. Among those who labor outdoors, agricultural workers enjoy the least protection. Despite this summer’s record heat, the United States still lacks a federal standard governing workplace exposure to extreme temperatures. According to the Occupational Safety and Health Administration, or OSHA, the agency has opened more than 4,500 heat-related inspections since March 2022, but it does not have data on worker deaths from heat-related illnesses.

Most states, particularly those led by Republicans, are loath to institute their own heat standards even as conditions grow steadily worse. In lieu of such regulation, the Coalition of Immokalee Workers, through its Fair Food Program, has adopted stringent heat protocols that, among other things, require regular breaks and access to water and shade. Such things are essential. Extreme heat killed at least 436 workers of all kinds, and sickened 34,000 more, between 2011 to 2021, according to NPR. Some believe that toll is much higher, and efforts like those Perez leads are providing a model for others working toward broader and more strictly enforced safeguards.

“We look to [the Fair Food Program] for best practices in terms of how can agricultural employers already begin to implement these kinds of protections,” said Oscar Londoño, the executive director of WeCount, which has been pushing for a heat standard in Miami-Dade County. “But we also believe that it’s important to have regulations and forcible regulation that covers entire industries.”

The Fair Food Program works with 29 farms, which raise more than a dozen different crops, and the buyers who rely upon them. In exchange for guaranteeing workers basic rights, participating growers and buyers, including Walmart, Trader Joe’s, and McDonald’s, receive a seal of approval that signals to customers that the produce they are buying was grown and harvested in fair, humane conditions.

To protect workers, the guidelines require 10-minute breaks every two hours and access to shade and water. The program also extended the time frame during which those things must be offered, from five months to eight, reducing the amount of time that workers are exposed to the worst heat of the year. Growers also must be aware of the signs of heat stress and monitor workers for them. Such steps are vital, particularly in humid conditions, to prevent acute heatstroke and safeguard employees’ long-term health. Repeated exposure to extreme temperatures can cause kidney disease, heat stroke, cardiovascular failure, and other illnesses.

“Having time to rest and cool down is very important to reduce the risk of death and injury from heat stress, because the damage that heat causes to the body is cumulative,” said Mayra Reiter, director of occupational safety and health at the advocacy organization Farmworker Justice. “Workers who are not given rest periods to recover face greater health risks.”

Such risks were very real for Perez, who worked various vegetable farms around Immokalee and along the East Coast before becoming an educator and advocate. Because most farm workers are paid according to how much they harvest, few feel they can spend a few minutes in the shade sipping a beverage.

“The difficulty of the work makes you feel like it takes years off your life,” Lupe Gonzalo, a member of Coalition of Immaokalee Workers, wrote in a public blog post. High humidity makes things worse, and those who rely upon employer-provided housing often find no relief after a day in the fields because many accommodations lack air conditioning, she wrote.

Abusive conditions can compound the deadly conditions. A 2022 investigation by the Department of Labor revealed poor conditions, including human trafficking and wage theft, at farms across South Georgia. Two workers experienced heat illness and organ failure, and others were held at gunpoint to keep them in line as they labored.

Many were workers holding H-2A visas in a program that has its roots in the Mexican Farm Labor Program, launched in 1942, that sponsored seasonal agricultural workers from Mexico. (Currently, the U.S. Department of Homeland Security issues those visas.) Because of their reliance on employers for housing, visa sponsorship, and employment, many workers experience abuse, an investigation by Prism, Futuro Media, and Latino USA found earlier this year.

It doesn’t help that federal labor law, including the National Labor Relations Act, doesn’t cover agricultural workers in the same way it protects employees in other sectors, said James Brudney, a professor of labor and employment law at Fordham University. Additionally, language barriers, fear of retaliation, and workers who come from a variety of backgrounds and cultures keep many from speaking out.

Perez remembers having only bad options for dealing with adverse working conditions: Deal with it, complain and risk being fired, or quit. The Fair Food Program gives workers recourse he never had, and builds on protections against forced labor, sexual harassment, and other abuses it has achieved with workers, growers, and buyers, which have agreed not to buy from farm operators with spotty records, since 2011.

Workers are regularly informed of their rights, and violations can be reported to the Fair Food Program through a hotline for investigation. Heat-related complaints have grown increasingly common in recent years, and often lead to a confidential arbitration process. Such inquiries may lead to mandatory heat safety training and stipulations growers must abide by. Findings of more serious allegations, such as sexual harassment, can lead to a grower being suspended or even removed from the program. Such efforts protect workers, hold employers accountable, and allow the program to know what’s most impacting laborers, said Stephanie Medina, a human rights auditor with the Fair Food Standards Council.

“With the record heat, every summer has definitely, I think, gotten a lot more difficult for workers out there,” Medina said. “I think that is one of the reasons why we put so much emphasis on getting the heat stress protocols together and implemented in the program.”

Growers must report every heat-related illness or injury, which is investigated by Medina’s team or an outside investigator depending on severity. Her team visits every participating grower annually. Many of them go beyond the program’s requirements to ensure worker safety, by, say, providing Gatorade and snacks and regularly checking in on those who have experienced heat-related illness, she said. Workers, too, are being more assertive in protecting themselves, reporting any violations because they know they cannot be retaliated against.

Though no growers or farmer’s associations responded to Grist’s requests for comment, some at least appear happy with the organization’s work. “The Fair Food Program is giving us structure and is a tool for better understanding in a workplace that is multicultural and multiracial,” Bloomia, a flower producer and FFP participant, said in a statement on the program’s website.

Still, some farm workers’ organizations, while supportive of the program’s work, doubt that farm-by-farm solutions will ever be enough to protect a majority of farm workers. Jeannie Economos, of the Farmworkers’ Association of Florida, said comprehensive policy-level solutions are required. She noted that even in Florida nurseries, greenhouses, and other growers of ornamental plants employ thousands of people who are not yet covered by the Fair Food Program. Although they one day may be, federal, state, and local regulations are needed to ensure sweeping safety reforms.

“So what do we think of the Fair Food Program? It’s good,” she said. “But it’s not far-reaching enough.”

Other campaigns are working toward legislative solutions. An effort called ¡Que Calor! in Miami-Dade County, led by WeCount, has been pushing the issue for years, and in many ways is inspired by what the Coalition of Immokalee Workers has accomplished, Londoño told Grist.

“Miami-Dade is on the verge of passing the first county-wide [standard] in the country, and it would protect more than 100,000 outdoor workers in both agriculture and construction,” he said “In the absence of a federal rule, and in the absence of state protections, local governments can play a foundational role in piloting policies that states and the entire federal government can take on.”

¡Que Calor!, has, like the Fair Food Program, been led by workers. Including them in drafting policies can help ensure they are effective because “they know what their risks and the threats to their well being are better than anyone,” Brudney, the Fordham University professor, said

Yet even jurisdictions with strict labor laws can see their protections undercut because they often rely on employees, who may face reprisals, to report violations. Miami-Dade’s proposal skirts that by creating a county Office of Workplace Health with broad powers to receive complaints, initiate inspections, interview workers, and adjudicate investigations.

Amid such victories and a mounting need to protect workers, the Fair Food Program plans to expand its reach. It has cropped up at tomato farms in Georgia and Tennessee; crept up the East Coast to lettuce, sweet potato, and squash farms in North Carolina, New Jersey, Maryland, and Vermont; and sprouted on sweet corn farms in Colorado and sunflower farms in California. Organizers from the Fair Food Program have in recent weeks met with growers and workers in Chile eager to bring its efforts there.

The organization hopes to see its principals embraced more widely, and continues to pressure more companies, including Wendy’s and the Publix supermarket chain, to buy into the effort. Medina says such an effort will require staffing up, but she’s confident in its chances of success.

Many growers willfully neglect the rights and needs of workers, making such efforts essential, Perez said. The need for victories like those already seen on farms that work with the program will only grow more acute as the planet continues to warm. Even if federal heat standards are adopted, Perez believes local worker-led accountability processes will still be needed to ensure growers follow the law.

“What we see the Fair Food Program as is both a method of education and a way to share information with workers about these risks,” he said, “and at the same time as a tool for workers to protect themselves against the worst effects of climate change on a day to day basis.”

This story was originally published by Grist with the headline How Florida farm workers are protecting themselves from extreme heat on Oct 27, 2023.

Ohio oil and gas industry accident data boost worries about drilling under state parks

Public records show Ohio regulators log hundreds of incidents each year dealing with chemical releases related to the oil and gas industry.

Such events raise critics’ concerns about plans to drill for oil and gas under state-owned parks and wildlife areas. While most problems happen at rigs and wellheads, which will be outside the parks, critics say airborne releases of methane or other chemicals would not be limited to property boundaries. And they fear that runoff could reach groundwater or surface water sources for state parks and nearby areas.

Jenny Morgan, a volunteer with the group Save Ohio Parks, said she asked the Ohio Department of Natural Resources for public records after Rob Brundrett, president of the Ohio Oil and Gas Association, said in a radio appearance last month that environmental problems and safety-related events “are certainly isolated events” when considered in light of the amount of industrial activity over the past 13 years.

Brundrett told the Energy News Network the state has nearly 63,000 oil and gas wells and thousands of miles of gas pipelines. And he focused on incidents that rose to the level of “major” or “severe” problems.

Morgan said the ODNR documents provide a very different perspective.

She also noted an event earlier this week, where a gas leak at a Guernsey County well pad triggered a mandatory evacuation within a half-mile radius. The sheriff lifted the order Monday night, but cautioned residents to seek medical attention if they had headaches, dizziness or trouble breathing.

The ODNR spreadsheets sent to Morgan last week show approximately 1,530 incidents from the start of 2018 through Sept. 10 of this year.

Agency personnel classified three events as “major” or “severe,” meaning they presented relatively high degrees of public safety or environmental impacts. They took up to a day or longer to control and required involvement by multiple agencies.

A “major” event on July 11 required the evacuation of more than 450 people in Columbiana County due to a well pad gas leak, for example.

Another two dozen incidents rose to the level of “moderate” events. ODNR’s spreadsheets say those events involved “considerable” public safety or environmental impacts. Problems took up to 12 hours to control, often with involvement from multiple agencies. Chemical releases exceeded various regulatory reporting thresholds.

Roughly 790 events during the nearly six-year period fit into ODNR’s “minor” category. The spreadsheets indicate those situations were stabilized in less than four hours with minimal public safety or environmental impact.

On Sept. 4, for example, a landowner accidentally struck a line with a brush hog, causing a gas leak. On Aug. 29, crude oil from a small flowline leak in Carroll County reached a dry ditch. On April 24, a Guernsey County site had a combustor fire while a truck was loading up at a well pad. A Jan. 7 “loss of well control” led to small amounts of brine on the soil and drainage area for a Noble County site.

Many of the remaining 600 or so events on the spreadsheets reflected referrals from other agencies, cases where ODNR gave technical assistance and matters outside the scope of ODNR’s oil and gas management work.

Events within ODNR’s jurisdiction dealt with oil and gas or brine and other fluids from both conventional and fracked horizontal wells.

“The ODNR Division of Oil and Gas Resources management will continue to carry out regulations set by statute and work to respond to incidents that need to be addressed,” said spokesperson Andy Chow, responding to the Energy News Network’s request for comment about public concerns over releases of oil, gas, brine or other materials into the environment.

“We’re just astounded at the fact that you could have this number of accidents and say that the oil and gas industry is safe,” said Melinda Zemper, another Save Ohio Parks member. The group is planning a rally at the Ohio Statehouse on Friday, Oct. 27, at noon.

Understating problems?

ODNR’s categories seem to understate the problem, said Silverio Caggiano, a hazardous materials expert whose three decades of experience includes work with the Youngstown Fire Department and Mahoning County hazardous materials team.

For example, ODNR categorized as moderate a June 2019 Harrison County event where explosions and fire damaged nine tanks in the wake of thunderstorms at a fracked well site. The report surmises that most well condensate and brine burned. But approximately 11,000 gallons of brine were released onto a well pad. Booms and pads were needed to stop flow where the well pad’s containment was damaged.

“Moderate” events earlier this year include an April 4 wellhead fire and a June 1 explosion.

A “minor” event on Feb. 1, 2019, released approximately four barrels of brine at an injection well site in Licking County due to frozen pipes. The spill was apparently contained on the well pad, but trucks for cleanup couldn’t reach the site right away due to a snow emergency.

Multiple incidents in the ODNR spreadsheets involve injection wells and transport of brine or other waste fluids. Brine is super salty water that comes up from wells. It often has elevated levels of heavy metals, as well as naturally occurring radioactive material. Brine waste is generally disposed of in underground injection wells.

The oil and gas industry also adds chemicals to fluids pumped into horizontal wells shortly after drilling to fracture, or frack, shale rock so oil and gas can flow out. Much of the fluids comes back up before oil and gas production begins and most of the waste must also be disposed of in deep injection wells.

“The sad thing is that a lot of these chemicals are unknown because they don’t have safety data sheets with them,” Caggiano said.

Even if one excludes complaints about odor, smell or plain informational reports, “you’re still looking at 50 to 60 calls a year” statewide, Caggiano added.

In Caggiano’s view, an average of one call a week, even for “minor” incidents, belies the industry’s claims that there are few problems. Even quickly cleaned-up releases involve chemicals that can be toxic, he said. And “obviously [prevention plans] didn’t work, because you had an incident,” he said.

“The fact that there have been only three major incidents since 2018 is a testament to the industry’s rigorous safety standards and practices,” said Brundrett at the Ohio Oil and Gas Association. “Considering that only .004% of Ohio oil and gas operations have had a major reportable incident during that timeframe, I would put our industry’s safety numbers against any other manual industry in Ohio.”

The information from the spreadsheets also “highlights the important steps of transparency and government cooperation that the oil and gas industry has adopted to minimize risk to the environment, our employees and the people of Ohio,” Brundrett added.

However, critics don’t discount “moderate” or even “minor” events.

“The cost is the collateral damage to the people and the environment in these areas,” said Roxanne Groff, another member of Save Ohio Parks.

The logged incidents also raise worries for her and others about proposals to drill under Ohio state-owned lands, including Salt Fork and Wolf Run state parks and Valley Run and Zepernick wildlife areas.

“What if it happens around Salt Fork? What if it goes into one of the major feeds into Wolf Run or Salt Fork Lake?” Groff said.The Ohio Oil and Gas Land Management Commission plans to rule on the proposals to drill under ODNR land before the end of the year.

Ohio oil and gas industry accident data boost worries about drilling under state parks is an article from Energy News Network, a nonprofit news service covering the clean energy transition. If you would like to support us please make a donation.

States opposed tribes’ access to the Colorado River 70 years ago. History is repeating itself.

A lawyer named T.F. Neighbors, who was special assistant to the U.S. attorney general, foresaw the likely outcome if the federal government failed to assert tribes’ claims to the river: States would consume the water and block tribes from ever acquiring their full share.

This story is the sixth in our Waiting for Water series about the Colorado River. Get this and other great reporting from High Country News by signing up for our newsletter.

In 1953, as Neighbors helped prepare the department’s legal strategy, he wrote in a memo to the assistant attorney general, “When an economy has grown up premised upon the use of Indian waters, the Indians are confronted with the virtual impossibility of having awarded to them the waters of which they had been illegally deprived.”

As the case dragged on, it became clear the largest tribe in the region, the Navajo Nation, would get no water from the proceedings. A lawyer for the tribe, Norman Littell, wrote then-Attorney General Robert F. Kennedy in 1961, warning of the dire future he saw if that were the outcome. “This grave loss to the tribe will preclude future development of the reservation and otherwise prevent the beneficial development of the reservation intended by the Congress,” Littell wrote.

Both warnings, only recently rediscovered, proved prescient. States successfully opposed most tribes’ attempts to have their water rights recognized through the landmark case, and tribes have spent the decades that followed fighting to get what’s owed to them under a 1908 Supreme Court ruling and long-standing treaties.

The possibility of this outcome was clear to attorneys and officials even at the time, according to thousands of pages of court files, correspondence, agency memos and other contemporary records unearthed and cataloged by University of Virginia history professor Christian McMillen, who shared them with ProPublica and High Country News. While Arizona and California’s fight was covered in the press at the time, the documents, drawn from the National Archives, reveal telling details from the case, including startling similarities in the way states have rebuffed tribes’ attempts to access their water in the ensuing 70 years.

Many of the 30 federally recognized tribes in the Colorado River Basin still have been unable to access water to which they’re entitled. And Arizona for years has taken a uniquely aggressive stance against tribes’ attempts to use their water, a recent ProPublica and High Country News investigation found.

“It’s very much a repeat of the same problems we have today,” Andrew Curley, an assistant professor of geography at the University of Arizona and member of the Navajo Nation, said of the records. Tribes’ ambitions to access water are approached as “this fantastical apocalyptic scenario” that would hurt states’ economies, he said.

Arizona sued California in 1952, asking the Supreme Court to determine how much Colorado River water each state deserved. The records show that, even as the states fought each other in court, Arizona led a coalition of states in jointly lobbying the U.S. attorney general to cease arguing for tribes’ water claims. The attorney general, bowing to the pressure, removed the strongest language in the petition, even as Department of Justice attorneys warned of the consequences. “Politics smothered the rights of the Indians,” one of the attorneys later wrote.

“This grave loss to the tribe will preclude future development of the reservation and otherwise prevent the beneficial development of the reservation intended by the Congress.”

The Supreme Court’s 1964 decree in the case quantified the water rights of the Lower Basin states — California, Arizona and Nevada — and five tribes whose lands are adjacent to the river. While the ruling defended tribes’ right to water, it did little to help them access it. By excluding all other basin tribes from the case, the court missed an opportunity to settle their rights once and for all.

The Navajo Nation — with a reservation spanning Arizona, New Mexico and Utah — was among those left out of the case. “Clearly, Native people up and down the Colorado River were overlooked. We need to get that fixed, and that is exactly what the Navajo Nation is trying to do,” said George Hardeen, a spokesperson for the Navajo Nation.

Today, millions more people rely on a river diminished by a hotter climate. Between 1950 and 2020, Arizona’s population alone grew from about 750,000 to more than 7 million, bringing booming cities and thirsty industries.

Meanwhile, the Navajo Nation is no closer to compelling the federal government to secure its water rights in Arizona. In June, the Supreme Court again ruled against the tribe, in a separate case, Arizona v. Navajo Nation. Justice Neil Gorsuch cited the earlier case in his dissent, arguing the conservative court majority ignored history when it declined to quantify the tribe’s water rights.

McMillen agreed. The federal government “rejected that opportunity” in the 1950s and ’60s to more forcefully assert tribes’ water claims, he said. As a result, “Native people have been trying for the better part of a century now to get answers to these questions and have been thwarted in one way or another that entire time.”

Three missing words

As Arizona prepared to take California to court in the early 1950s, the federal government faced a delicate choice. It represented a host of interests along the river that would be affected by the outcome: tribes, dams and reservoirs and national parks. How should it balance their needs?

The Supreme Court had ruled in 1908 that tribes with reservations had an inherent right to water, but neither Congress nor the courts had defined it. The 1922 Colorado River Compact, which first allocated the river’s water, also didn’t settle tribal claims.

In the decades that followed the signing of the compact, the federal government constructed massive projects — including the Hoover, Parker and Imperial dams — to harness the river. Federal policy at the time was generally hostile to tribes, as Congress passed laws eroding the United States’ treaty-based obligations. Over a 15-year period, the country dissolved its relationships with more than 100 tribes, stripping them of land and diminishing their political power. “It was a very threatening time for tribes,” Curley said of what would be known as the Termination Era.

Tribal water rights were “prior and superior” to all other water users in the basin, even states.

So it was a shock to states when, in November 1953, Attorney General Herbert Brownell Jr. and the Department of Justice moved to intervene in the states’ water fight and aggressively staked a claim on behalf of tribes. Tribal water rights were “prior and superior” to all other water users in the basin, even states, the federal government argued.

Western states were apoplectic.

Arizona Gov. John Howard Pyle quickly called a meeting with Brownell to complain, and Western politicians hurried to Washington, D.C. Under political pressure, the Department of Justice removed the document four days after filing it. When Pyle wrote to thank the attorney general, he requested that federal solicitors work with the state on an amended version. “To have left it as it was would have been calamitous,” Pyle said.

The federal government refiled its petition a month later. It no longer asserted that tribes’ water rights were “prior and superior.”

When details of the states’ meeting with the attorney general emerged in court three years later, Littell, the Navajo Nation’s attorney, berated the Department of Justice for its “equivocating, pussy-footing” defense of tribes’ water rights. “It is rather a shocking situation, and the Attorney General of the United States is responsible for it,” he said during court hearings.

Arizona’s legal representative balked at discussing the meeting in open court, calling it “improper.”

Experts told ProPublica and High Country News that it’s impossible to quantify the impact of the federal government’s failure to fully defend tribes’ water rights. Reservations might have flourished if they’d secured water access that remains elusive today. Or, perhaps basin tribes would have been worse off if they had been given only small amounts of water. Amid the overt racism of that era, the government didn’t consider tribes capable of extensive development.

Jay Weiner, an attorney who represents several tribes’ water claims in Arizona, said the important truth the documents reveal is the federal government’s willingness to bow to states instead of defending tribes. Pulling back from its argument that tribes’ rights are “prior and superior” was but one example.

“It’s not so much the three words,” Weiner said. “It’s really the vigor with which they would have chosen to litigate.”

“It is rather a shocking situation, and the Attorney General of the United States is responsible for it.”

Because states succeeded in spiking “prior and superior,” they also won an argument over how to account for tribes’ water use. Instead of counting it directly against the flow of the river, before dealing with other users’ needs, it now comes out of states’ allocations. As a result, tribes and states compete for the scarce resource in this adversarial system, most vehemently in Arizona, which must navigate the water claims of 22 federally recognized tribes.

In 1956, W.H. Flanery, the associate solicitor of Indian Affairs, wrote to an Interior Department official that Arizona and California “are the Indians’ enemies and they will be united in their efforts to defeat any superior or prior right which we may seek to establish on behalf of the Indians. They have spared and will continue to spare no expense in their efforts to defeat the claims of the Indians.”

Western states battle tribal water claims

As arguments in the case continued through the 1950s, an Arizona water agency moved to block a major farming project on the Colorado River Indian Tribes’ reservation until the case was resolved, the newly uncovered documents show. Decades later, the state similarly used unresolved water rights as a bargaining chip, asking tribes to agree not to pursue the main method of expanding their reservations in exchange for settling their water claims.

Highlighting the state’s prevailing sentiment toward tribes back then, a lawyer named J.A. Riggins Jr. addressed the river’s policymakers in 1956 at the Colorado River Water Users Association’s annual conference. He represented the Salt River Project — a nontribal public utility that manages water and electricity for much of Phoenix and nearby farming communities — and issued a warning in a speech titled, “The Indian threat to our water rights.”

“I urge that each of you evaluate your ‘Indian Problem’ (you all have at least one), and start NOW to protect your areas,” Riggins said, according to the text of his remarks that he mailed to the Bureau of Indian Affairs.

Riggins, who on multiple occasions warned of “‘Indian raids’ on western non-Indian water rights,” later lobbied Congress on Arizona’s behalf to authorize a canal to transport Colorado River water to Phoenix and Tucson. He also litigated Salt River Project cases as co-counsel with Jon Kyl, who later served as a U.S. senator. (Kyl, who was an architect of Arizona’s tribal water rights strategy, told ProPublica and High Country News that he wasn’t aware of Riggins’ speech and that his work on tribal water rights was “based on my responsibility to represent all of the people of Arizona to the best of my ability, which, of course, frequently required balancing competing interests.”)

While Arizona led the opposition to tribes’ water claims, other states supported its stance.

“We thought the allegation of prior and superior rights for Indians was erroneous,” said Northcutt Ely, California’s lead lawyer in the proceedings, according to court transcripts. If the attorney general tried to argue that in court, “we were going to meet him head on,” Ely said.

When Arizona drafted a legal agreement to exclude tribes from the case, while promising to protect their undefined rights, other states and the Interior Department signed on. It was only rejected in response to pressure from tribes’ attorneys and the Department of Justice.

McMillen, the historian who compiled the documents reviewed by ProPublica and High Country News, said they show Department of Justice staff went the furthest to protect tribal water rights. The agency built novel legal theories, pushed for more funding to hire respected experts and did extensive research. Still, McMillen said, the department found itself “flying the plane and building it at the same time.”

Tribal leaders feared this would result in the federal government arguing a weak case on their behalf. The formation of the Indian Claims Commission — which heard complaints brought by tribes against the government, typically on land dispossession — also meant the federal government had a potential conflict of interest in representing tribes. Basin tribes coordinated a response and asked the court to appoint a special counsel to represent them, but the request was denied.

So too was the Navajo Nation’s later request that it be allowed to represent itself in the case.

Arizona v. Navajo Nation

More than 60 years after Littell made his plea to Kennedy, the Navajo Nation’s water rights in Arizona still haven’t been determined, as he predicted.

The decision to exclude the Navajo Nation from Arizona v. California influenced this summer’s Supreme Court ruling in Arizona v. Navajo Nation, in which the tribe asked the federal government to identify its water rights in Arizona. Despite the U.S. insisting it could adequately represent the Navajo Nation’s water claims in the earlier case, federal attorneys this year argued the U.S. has no enforceable responsibility to protect the tribe’s claims. It was a “complete 180 on the U.S.’ part,” said Michelle Brown-Yazzie, assistant attorney general for the Navajo Nation Department of Justice’s Water Rights Unit and an enrolled member of the tribe.

In both cases, the federal government chose to “abdicate or to otherwise downplay their trust responsibility,” said Joe M. Tenorio, a senior staff attorney at the Native American Rights Fund and a member of the Santo Domingo Pueblo. “The United States took steps to deny tribal intervention in Arizona v. California and doubled down their effort in Arizona v. Navajo Nation.”

In June, a majority of Supreme Court justices accepted the federal government’s argument that Congress, not the courts, should resolve the Navajo Nation’s lingering water rights. In his dissenting opinion, Gorsuch wrote, “The government’s constant refrain is that the Navajo can have all they ask for; they just need to go somewhere else and do something else first.” At this point, he added, “the Navajo have tried it all.”

The federal government chose to “abdicate or to otherwise downplay their trust responsibility.”

As a result, a third of homes on the Navajo Nation still don’t have access to clean water, which has led to costly water hauling and, according to the Navajo Nation, has increased tribal members’ risk of infection during the COVID-19 pandemic.

Eight tribal nations have yet to reach any agreement over how much water they’re owed in Arizona. The state’s new Democratic governor has pledged to address unresolved tribal water rights, and the Navajo Nation and state are restarting negotiations this month. But tribes and their representatives wonder if the state will bring a new approach.

“It’s not clear to me Arizona’s changed a whole lot since the 1950s,” Weiner, the lawyer, said.

Anna V. Smith is an associate editor of High Country News. She writes and edits stories on tribal sovereignty and environmental

justice for the Indigenous Affairs desk from Colorado. @annavtoriasmith

Mark Olalde is an environment reporter with ProPublica, where he investigates issues concerning oil, mining, water and other topics around the Southwest.

We welcome reader letters. Email High Country News at editor@hcn.org or submit a letter to the editor. See our letters to the editor policy.

Human Remains From Lahaina Wildfire Found In Courthouse

Maui police also said the number of people who have not been accounted for since the Aug. 8 fire dropped to seven.

15 months after a flash flood devastated parts of Southwest Virginia, state aid is on the way

More than a year after a devastating flash flood hit Buchanan and Tazewell counties, residents whose property was damaged or destroyed can finally start the process of applying for state flood relief money.

Delegate Will Morefield, R-Tazewell County, who was instrumental in securing the $18 million, said Friday he hopes those who qualify will receive the money before the end of the year.

To help affected residents get the application process started, information sessions will be held Wednesday in Bandy and Whitewood.

“Many of the flood victims lost everything they own with no ability to rebuild. The assistance will give them hope for a better future,” said Morefield.

Morefield said a crowd is expected at the meeting in Whitewood, where there was a lot of property lost and damaged.

Buddy Fuller, a retired resident of Whitewood who has rental properties in three counties, said he plans to be at the meeting Wednesday. He hopes to recoup some of the money he’s spent cleaning up a trailer park he owns off Dismal River Road and wants to rebuild, an apartment building in Whitewood, a number of damaged rental properties and a barn, and replace some sheep that got washed away.

Flood relief information sessions

Meetings about how to apply for state aid will be held Wednesday for residents of Buchanan and Tazewell counties whose homes were damaged or destroyed in the July 2022 flash flood.

Tazewell County: 4:30 p.m., Bandy Community Center, 3290 Bandy Road

Buchanan County: 7 p.m., Whitewood Community Center, 7424 Dismal River Road

He said those in the community don’t seem to be angry over the budget impasse that held up the relief funding because they knew it would eventually come through.

“We’ve just been waiting,” Fuller said Friday. “I know with our legislators, Morefield and Hackworth [Sen. Travis Hackworth, R-Tazewell County], if there’s any way to get the money, they’re going to get it for us.”

As with the relief fund for those hit by flooding in August 2021 in the town of Hurley in Buchanan County, the money will go through the Virginia Department of Housing and Community Development, which is hosting the community sessions. The meetings are open to the public and no registration is required, Morefield said.

The meetings will include information about the application process, eligibility requirements and program guidelines to assist residents in applying for the disaster relief program, according to DHCD.

The relief program will offer a grant of 175% of the local assessed value for property that is classified a total loss or had major damage. For properties that can be repaired, eligible applicants can receive assistance to make repairs or be reimbursed for work that has already been done.

The devastating flash flooding hit parts of eastern Buchanan County and western Tazewell County on the night of July 12, when about 6 inches of rain fell over just a few hours. The resulting flooding damaged roads and bridges, destroyed homes and caused power and water outages. There were no reported deaths or injuries.

According to an online dashboard maintained by United Way of Southwest Virginia, a lead agency in the recovery effort, 21 homes were destroyed; as of Aug. 31, six had been built to replace them. Another 25 had major damage of $10,000 or more, and 18 had been repaired. Twenty-five more homes saw damage of $10,000 or less.

So far, United Way has spent $574,441 on the repairs and construction and $225,049 remains, the dashboard states. All of the money came from donations.

Less than a year earlier, a similar storm occurred in the Guesses Fork area of Hurley, a community about 30 miles away. It also resulted in major flooding, the destruction or damage to dozens of homes and the death of one woman.

Following both storms, the Federal Emergency Management Agency denied financial help to individual homeowners, saying that the damage wasn’t significant enough to warrant aid. Most of the homeowners did not carry flood insurance.

FEMA’s response to the Hurley disaster prompted Morefield to propose a statewide flood recovery fund that would pay for property losses that weren’t covered by insurance or federal aid. There was a budget earmark of $11.4 million for Hurley relief.

Initially, Morefield had sought $11 million in relief money for the areas hit by the July 2022 flooding, but he increased the amount to $18 million when local damage estimates increased.

Those in Hurley also had to wait for state relief money due to a budget stalemate, although it had been ironed out by June 2022. The first state funds went to Hurley residents in December 2022 — 16 months after the flooding.

It’s been 15 months since the Whitewood flooding.

Local and state officials have said the Hurley flood left them better prepared for the Whitewood disaster, and they decided that the framework developed for the Hurley relief money will be used for Whitewood.

As with the Hurley flooding, those who want to be reimbursed for work that’s already been done must provide receipts, Morefield said.That requirement slowed down the process in Hurley, as did a shortage of contractors to do the work.

Applicants in Buchanan County can apply at the Buchanan County Department of Social Services in Grundy, while those in Tazewell County can apply at the Tazewell County Administration Office on Main Street in Tazewell.

“We are excited to start taking applications and get the much-needed assistance to the flood victims,” Morefield said. “The program is unlike any flood relief program in the United States and the governor referred to it as a model program. Our region is grateful the General Assembly and the governor offered their support for our request during a time of crisis. I have been extremely impressed with the Department of Housing and Community Development and all of the local partners for their commitment to help.”

The post 15 months after a flash flood devastated parts of Southwest Virginia, state aid is on the way appeared first on Cardinal News.

In Puerto Rico, residents wait for accountability, cleanup of toxic coal ash ‘caminos blancos’

The nearly 14 million people of color who live in rural America face unique challenges that run the gamut — from industry land grabs to struggles with broadband and a lack of representation in business and in government that makes it near impossible for many to cultivate generational wealth. This six-part series from the Rural News Network, with support from the Walton Family Foundation, elevates the issues these communities are facing and what some are doing to change their fates.

SALINAS, Puerto Rico — After Sol Piñeiro retired from bilingual special education in New Jersey public schools, she bought a dream house in Salinas on Puerto Rico’s south coast, near the town where she was born.

She and her husband built a traditional Puerto Rican casita beside the main home and filled the sprawling yard with orchids, cacti and colorful artifacts, including a bright red vintage pickup truck.

Only after setting up her slice of paradise here did she learn the road running alongside it contained toxic waste from a nearby power plant.

Salinas is one of 14 municipalities around the island that between 2004 and 2011 used coal ash as a cheap material to construct roads and fill land. The material is a byproduct of burning coal and is known to contain a long list of toxic and radioactive chemicals. But the U.S. Environmental Protection Agency did not specifically regulate coal ash until 2015, and those regulations don’t cover the coal ash used in roads like that in Salinas.

Any community with a coal-burning power plant likely has tons of toxic coal ash stored somewhere nearby, in pits, ponds or piles. In 2015, the EPA announced new rules requiring groundwater testing and safer storage and disposal methods, but the rules exempt power companies from responsibility for ash dispersed for use in road building and other projects.

Scant or nonexistent recordkeeping makes comprehensively mapping this scattered coal ash impossible, but environmental and public health advocates suspect the material is likely contaminating groundwater and causing toxic dust across the United States.

Perhaps nowhere is the problem as prominent as on Puerto Rico’s south coast, a rural, economically struggling region far from the capital of San Juan and major tourist destinations. Here, coal ash — or “cenizas” in Spanish — has become a symbol of the environmental injustice that has long plagued the U.S. colony.

The ash originated from a coal-fired power plant owned by global energy company AES in the nearby town of Guayama. After the Dominican Republic began refusing imports of the waste, the company promoted the material to Puerto Rican municipalities and contractors as a construction fill product. In all, more than 1.5 million tons of coal ash were deposited in Salinas and Guayama, according to a 2012 letter by the company’s vice president that was obtained by the Puerto Rico-based Centro de Periodismo Investigativo, or Center for Investigative Journalism.

In July 2022, a decade after community pressure forced the company to stop marketing ash for such use, EPA Administrator Michael Regan visited Guayama and Salinas to meet with residents about coal ash and other environmental issues as part of his “Journey to Justice” tour. The tour also included the agency’s first Environmental Justice Advisory Council meeting in Puerto Rico. Piñeiro and others are glad for the attention, but given the U.S. government’s long history of broken promises and neglect in Puerto Rico, they are impatient for meaningful action.

Energy injustice

Piñeiro learned the backstory of the powdery gray road material when she connected with José Cora Collazo, who lives in a mint-green home perched on a hillside nearby, with sweeping views of the south coast. Piñeiro has since joined Cora in leading the organization Acción Social y Protección Ambiental, raising awareness about coal ash and demanding change from local and U.S. officials.

While the majority of Puerto Rico’s population lives on the north coast, including the San Juan area, the bulk of the island’s power is generated on the south coast, including at the AES coal plant as well as a nearby power plant that burns oil. That means the residents of Guayama, Salinas and other nearby communities could be subject to a myriad of public health risks, experts and activists say, while the mangrove ecosystem of Jobos Bay National Estuarine Research Reserve and area fisheries could also be threatened.

During frequent heavy rains, Piñeiro and Cora see the gray coal ash streaming down crumbling roads and into the tangled brush and creeks that traverse the hillsides. As Piñeiro’s picturesque homestead is on a slope below the road Calle Luis Llorens Torres, the coal ash runs down onto her property.

Local residents draw drinking water from their own private wells or a network of municipal wells, and they worry that coal ash is polluting the groundwater. In 2021, chemist Osvaldo Rosario spearheaded testing of tap water in area homes and found disturbing signs of contamination with toxic metals known to be in coal ash. In August, Rosario and colleagues retested the same homes and are awaiting results.

Rosario’s testing and ongoing activism by locals spurred the U.S. EPA to do its own groundwater testing this spring. EPA spokesperson Robert Daguillard previously told the Energy News Network the agency anticipated presenting the results in late September; EPA did not respond to a recent query about the status of the results.

“EPA’s focus on CCR [coal combustion residuals] in Puerto Rico follows the commitment made by Administrator Regan during his Journey to Justice visit with communities concerned with the management of CCR in Puerto Rico,” Daguillard said in response to the Energy News Network’s questions.

Broken promises, problematic offers

When AES built the coal plant, it promised the resulting ash would be shipped off the island. An investigation by Centro de Periodismo Investigativo revealed that in its first two years of operation, more than 100 million tons of coal ash from the plant were sent to the Dominican Republic, dumped in and around the town of Arroyo Barril and several ports. Soon residents noticed a spike in birth defects, miscarriages and other ailments, which experts attributed to the coal ash pollution.

The country barred coal ash imports. In U.S. court, AES agreed to pay $6 million to remove the coal ash. Meanwhile, AES began marketing the byproduct in Puerto Rico as a construction fill under the brand name Agremax. The ash was used in the wealthy San Juan-area town of Dorado and the university town of Mayaguez on the west coast, but use was heaviest on the south coast.

“They began dumping the ash in many areas of Puerto Rico as the base for many roads, many trails, unpaved trails of pure ash,” Rosario said. “They would fill in flood-prone areas so there could be construction. There was illegal dumping in many open areas. They literally gave the ash away; they paid for the transportation. A contractor would say, ‘I need 20 tons of coal ash to fill in this area,’ and they would bring the coal ash.”

A 2023 report by the environmental organization Earthjustice noted that the toxic ash still lies unused and uncovered at sites where it poses health risks to people in nearby homes, parks, a school and a hospital. “At numerous sites, the coal ash was left uncovered or covered only with a thin layer of dirt, which quickly eroded,” the report said. “Fugitive dust from these uncovered piles and roads is common.”

Rosario said that the use of coal ash was done “under the permissive oversight of government agencies.”

“You put a couple inches of topsoil over it, then when that topsoil gets eroded away or you dig to plant a tree, you reach this gray material which is the ash,” he said. “The water level is not far below that. This was done behind the backs of the people. They got mortgages for houses built on toxic material.”

Unencapsulated ash

In 2012, Vanderbilt University tested Agremax at the behest of the U.S. EPA. It found that the material — a mix of fly ash and bottom ash — leached high concentrations of arsenic, boron, chloride, chromium, fluoride, lithium and molybdenum.

Coal ash is commonly used as a component in concrete, and it is widely considered safe when it is encapsulated in such material.

But unencapsulated use of coal ash, while legal, is opposed by environmental groups who fear that the dangerous heavy metals known to leach into groundwater can spread and potentially expose people to carcinogens and neurotoxins through drinking water, soil and air.

Advocates have long argued for stricter regulation of unencapsulated use of coal ash. As the Energy News Network explored in a 2022 investigation, throughout the U.S. developers can use up to 12,400 tons of unencapsulated coal ash without notifying the public.

There are about a billion tons of coal ash stored in impoundments and landfills around the U.S., and testing required under 2015 federal rules shows that almost all of it is contaminating groundwater, as Earthjustice, Environmental Integrity Project and other organizations have shown based on the companies’ own groundwater monitoring data. This summer, the EPA expanded what types of coal ash storage are subject to the rules, including ash at repositories that were closed before 2015.

Environmental groups filed a lawsuit last year demanding that the expanded rules also address ash used as structural fill in places like Salinas and Guayama.

But the agency did not mention such ash in its revision to the rules, with the draft released in May. In June, Cora traveled to Chicago to testify before the EPA. Unless they are changed, the rules leave his neighbors and others across Puerto Rico with few legal avenues to fight for accountability and remediation.

“The coal ash industry has their laboratories; they know what they are doing,” Rosario said. “I go back to the word ‘avarice’ — they know all of this, just like the tobacco industry.”

AES, which is headquartered in Arlington County, Virginia, did not respond to questions from the Energy News Network. A regional AES representative instead provided a statement saying: “For more than 20 years, AES Puerto Rico has been bringing safe, affordable, and reliable energy to the island and supplying up to 25% of the island’s energy needs. We remain committed to accelerating the responsible transition to renewable energy for the island and the people of Puerto Rico.”

A history of struggle

Cora was aware of environmental issues from childhood. His father, José Juan Cora Rosa, was a prominent activist who fought against the U.S. Navy’s bombing exercises on the Puerto Rican island of Vieques, among other iconic struggles.

The elder Cora explained that in the late 1990s, local resistance halted plans to build a coal plant in Mayaguez, the town on Puerto Rico’s west coast home to a prominent technical university. The coal plant was instead opened in 2002 in Guayama, despite opposition from the elder Cora and other residents. He said the company likely knew they’d face less pushback since Guayama’s population is smaller and economically struggling.

For years now, residents of Guayama and Salinas have complained of health effects — from tumors to skin disease — that they think are caused by the coal plant. A 2016 study by the University of Puerto Rico’s School of Public Health showed a disproportionately high incidence of respiratory disease, cardiovascular disease, asthma, hives and spontaneous abortions in Guayama. Other studies have found high cancer rates in the area, according to reporting by the Centro de Periodismo Investigativo.

Salinas resident Victor Alvarado Guzmán has seen such health issues firsthand. His wife is a cancer survivor, and he notes that on two blocks in the Miramar community of Guayama, 18 people have had cancer, some fatal cases.

“That’s not normal,” he said.

Alvarado is trained as a psychologist but has been an environmental activist for a quarter-century, fighting unsuccessfully against the coal plant and successfully to block a proposed landfill and chicken processing plant from the area. He’s co-founder of the grassroots environmental group Diálogo Ambiental, and he’s run for public office.

Sitting in a restaurant in Salinas built on a foundation of coal ash, Alvarado said he wants to see historic ash removed from the community, and he wants the government to pay for soil and water testing plus blood testing for residents to see how heavy metals from coal ash may be affecting them.

Under a gazebo in Guayama on a stifling hot August afternoon, local environmental activists gathered to discuss the risk from coal ash, and the plant’s air emissions.

“Every time we have a meeting, we hear about someone else who is sick,” noted Miriam Gallardo, a teacher who used to work at a school near the plant, seeing coal ash-laden trucks go by.

Aldwin Colón, founder of community group Comunidad Guayama Unidos Por Tu Salud — Guayama Community United for Your Health — said that on his block, people in four out of the nine homes have cancer. He said he blames the coal plant and the public officials who have not done more to protect residents. He noted that Puerto Rico Gov. Pedro Pierluisi was previously a lobbyist representing AES.

He lamented that the company chose to build the plant in a lower-income community with little tourism.

“In poor communities, we don’t have the resources to fight back,” Colón said, in Spanish. “These are criminal companies that use corrupt politics for their own means. This is racism and classism — the same old story, the slaves sacrificed for the patron.”

Colón, Piñeiro and Cora drove around the area with other activists from Guayama to show the Energy News Network multiple sites where coal ash is visible. They pulled over along a major road, Dulces Sueños — Sweet Dreams — built in recent years. One man dug a shovel into the embankment next to the road. After turning over a few inches of soil and foliage, his shovel filled with gray powder.

Continuing through Salinas and Guayama, Piñeiro pointed out the strip malls and fast food stores that were built on top of coal ash, among 36 specific locations documented by the Centro de Periodismo Investigativo.

Cora and Piñeiro noted the coal ash-laden “caminos blancos” — white roads, as they are commonly known — traversing the countryside, known as hot destinations for mountain bikers.

At a small store in Guayama, older men passed the sweltering afternoon sitting on plastic chairs sipping Medalla beers. The owner of the store, Jacob Soto Lopez, recounted how he used to jog on dirt roads in the nearby town of Arroyo — until he learned the dust he was kicking up was toxic coal ash. Now he frets about how it may be contaminating the drinking water.

“We sell bottled water here, but a lot of people can’t afford it,” he said. “They should stop producing the ashes and take away what they’ve thrown on our island.”

A revolt

On the mainland, many Americans are unaware of the threat posed by coal ash, or even its existence, since it is often stored on coal plant sites, in roads and berms, and in quarries, ravines, or old mines. The federal rules regulating coal ash that took effect in 2015 were barely enforced until 2022, when the EPA began issuing decisions related to the rules.

But in communities on Puerto Rico’s south coast, the term “cenizas” — ashes in Spanish — is often recognized as a signifier of injustice and popular struggle.

When AES offloaded Agremax for use in construction and fill starting in 2004, it’s possible local officials and others did not understand the risks. But concerns soon grew and multiple municipalities passed ordinances banning the storage of coal ash.

In 2016, residents of Peñuelas — 40 miles west of the plant — revolted over AES’ plan to truck ash to a landfill in their community, despite a municipal ordinance banning coal ash. Hundreds of people occupied the street, blocking trucks from entering the landfill, and dozens of arrests were made over several days in November 2016. AES stopped sending ash to Peñuelas.

Manuel “Nolo” Díaz, a leader of that movement, noted that locals were ready to snap into action since they had previously worked together to oppose a plan to build a gas pipeline through the area.

“We took over the street to enforce the law,” Díaz said, in Spanish. “It’s so beautiful when people come together to defend their rights. But the fight is not over until they remove the ashes from the 14 towns, and decontaminate the water they’ve contaminated.”

In 2017, the island’s government passed a law banning the storage of coal ash on the island. Since then, AES has shipped coal ash from the island to U.S. ports including Jacksonville, Florida, for storage in landfills in Georgia and elsewhere, the Energy News Network has reported.

While coal ash is no longer permanently stored in Puerto Rico, a mound of coal ash multiple stories high is visible at AES’ site, where it is allowed to be stored temporarily before transport. And coal ash still makes up the street above Piñeiro’s home and many others, creating milky gray rivulets running down the hills and likely percolating into drinking water sources.

A conundrum

The law against storing coal ash on the island could complicate efforts to remove it from roads and fill sites, since it would need to be transported and stored somewhere.

The Federal Emergency Management Agency allocated about $8 million for Salinas to repair roads in the wake of 2017’s Hurricane Maria. Cora, Piñeiro and others have demanded that the money be used to remove coal ash from roads and rebuild them.

Last year, Salinas Mayor Karilyn Bonilla Colón requested an exception to the law banning the disposal of coal ash on the island, so that coal ash could be extracted from the roads in Salinas and deposited in landfills in Ponce, Humacao or Peñuelas. She told local media that exporting the ash off the island would be too expensive.

Organizations in Peñuelas and beyond opposed the move, calling it disrespectful to their communities. In January, the natural resources department denied the mayor’s request.

Piñeiro and Cora are frustrated Bonilla has not found another way to remove and dispose of the ash. On Sept. 5, activists painted on the street in Salinas with large letters calling the mayor “asesina ambiental” — an environmental assassin.

A spokesperson for Bonilla said she is no longer doing interviews about coal ash, and referred the Energy News Network to local news coverage of the controversy.

Cora and other activists are now appealing to Manuel A. Laboy Rivera, the executive director of the Central Office for Recovery, Reconstruction and Resiliency which oversees FEMA fund distribution in Puerto Rico, since he recently warned that 80 municipalities, government agencies and organizations in Puerto Rico will have to return the emergency funds if they can’t prove they’ve been used.

Cora and Piñeiro note that many of their neighbors are elderly, and don’t feel urgency around coal ash after having survived two hurricanes and a major earthquake in the past six years, not to mention the island’s ongoing economic crisis.

“But what about future generations?” Piñeiro asked.

“If the aquifer is contaminated and we don’t have potable water in Salinas, how can people live here?” added Cora, in Spanish. “What can we do?”

Cora, Piñeiro and their allies want the coal plant to close and be replaced by clean energy, and indeed Puerto Rico has passed a law calling for a transition to 100% renewable energy by 2050. But they don’t want the clean energy transition to replicate the injustices of the fossil fuel economy, and they feel plans for massive solar farms on the south coast — developed in part by AES — could do just that.

While solar farms are emissions-free, they continue the problem of reliance on a fragile centralized grid and put the island’s energy burden on the south coast.

Opponents say the proposed massive arrays of solar panels cause flooding and erosion — by compacting land and causing run-off — while also displacing agricultural land. Attorney Ruth Santiago, who has lived most of her life in Salinas, is representing environmental groups that recently filed a lawsuit against the Puerto Rico government over 18 planned solar farms, including by AES.

On Aug. 7, Alvarado led activists from island-wide environmental groups in delivering a letter to Puerto Rico’s natural resources department in San Juan, making demands around coal ash, solar farms and other issues.

“Under the theme of an energy transition that is just and clean, how are they going to deal with the deposit of toxic ashes across the country?” said Vanessa Uriarte, executive director of the group Amigxs del Mar, in Spanish, outside the department’s office. “The department needs to tell us what their plan of action is to deal with this problem. And now the same company that has contaminated our community with coal ash is taking our agricultural lands for solar panels.”

Energy justice leaders instead want decentralized small solar and microgrids that are resilient during disasters and cause minimal environmental impacts so that future generations are not left with more injustices like coal ash.