Inside the last-ditch effort to stop the Mountain Valley Pipeline

As day broke over the small mountain town of Elliston, Virginia one Monday in October, masked figures in thick coats emerged from the woods surrounding a construction site. Three of them approached three excavators and, one by one, locked themselves to the machines, bringing the day’s work to a halt. As they did so, several dozen of their fellow protesters gathered around them, unfurling banners and chanting amidst the groaning and beeping of construction equipment.

They made their way across the field, over patches of bare earth, around sections of rusty pipe meant for burial beneath the mountain. Eventually the metal tubes will form yet another section of the Mountain Valley Pipeline, which will soon carry 2 billion cubic feet of fracked methane from the shalefields of West Virginia to North Carolina each day. Their breath billowed in the crisp air. Beyond them stretched a bright blue sky, and mountains tinged with yellow. The past night’s rain pooled on the muddy and compacted soil beneath their feet.

Workers in highlighter-yellow vests and hard hats milled around, some looking amused, others frustrated. One or two engaged with the protesters, only to be told off by an irate site manager. A few miles away at the West Virginia state line, another three dozen or so activists did much the same atop Peters Mountain. One even managed to crawl under an excavator and lock herself in place, despite the cold. The others rallied around, enclosing her in a tight, protective circle.

Some might wonder why they bothered. After all, the project is, by the Mountain Valley Pipeline company’s estimate, 94 percent complete and will be wrapped up before summer. It stalled for several years amid legal fights over various permits, but Senator Joe Manchin, a moderate Democrat from West VIrginia, almost single-handedly revived it in 2022 in exchange for his support of key Democratic priorities. Since then, the Biden administration and the Supreme Court have all but assured its completion. With the approximately 303-mile pipeline approaching the final stretch after almost a decade’s work, it might seem hardly worth fighting at this point.

A large contingent of steadfast opposition begs to differ, and will enthusiastically explain why. The pipeline is six years behind schedule, about half a billion dollars over budget, and, despite promises that it would be done by the end of last year, delayed once again. The remaining construction is over rugged terrain, with hundreds of water crossings left to bridge. The company recently postponed, shortened, and rerouted its planned extension into North Carolina, a proposal long stymied by permitting problems with the main line. And, just last month, Equitrans, which owns the pipeline and many others across the country, was said to be considering selling itself. The road to the pipeline’s completion remains rocky, its opponents argue, with many opportunities to make finishing it as difficult as possible.

“We cannot let them destroy our land and water,” said a young woman named Ericka. Like many interviewed for this story, she gave only her first name out of fear of reprisal from Mountain Valley Pipeline LLC, which has begun suing protesters in a bid to silence them. She had brought her three children to occupy the land that day. “What are we going to drink? Where are we going to live? People have to come here and stop this.”

Killing the project is their ideal outcome. Barring that, those who have for almost a decade packed public hearings, spent weeks at sit-ins and even lived high in trees for 932 days want to make building pipelines so time consuming, so expensive, so plain annoying, that fossil fuel companies and the politicians who support them think twice about greenlighting any more.

Even as pipeline crews continue steadily boring under rivers and felling trees, activists say each day they can delay construction is another day humanity delays the worst impacts of climate change. The increasingly grave personal and legal risks they face are, they say, worth it, if only for that.

“For five f****** years, we’ve fought you without fear,” sang the masked figures on Peters Mountain, and “we’ll fight you for five f****** more.”

Morning ripened over the ridge, and the fog rolled in, then out. The pipeline workers retreated, mostly without complaint — followed by the protestors’ calls of “Paid time off! Paid time off!” Some of those gathered began to sing: John Prine songs about beautiful landscapes stripped for coal, union songs, and striking miners’ ballads that reverberated through the same ridges long ago. When their voices grew weary, someone blared dance music through a loudspeaker as police cars rumbled up the gravel access road. They tried not to be afraid as the sirens grew louder, knowing the risk they had taken in coming here and knowing, as many said, that the time of act is now.

As the nation’s fracking boom reached coal country about a decade ago, pipelines carrying methane began to snake across the landscape. The Mountain Valley Pipeline, or MVP, met instant fury when Mountain Valley LLC proposed it in 2014. Opposition to the project drew a wide range of people, from farmers in West Virginia to Indigenous tribes in North Carolina, together in a united front. Some were alarmed by what it would mean for their land: Razed trees, disturbed landscapes, water running brown from the tap, and, in the end, a frightening risk of leaks and explosions. A pipeline in Pennsylvania run by one of the companies involved in MVP blew up late last year; a couple and their child suffered severe burns and barely escaped with their lives. Then there’s the longer term, irreversible danger of the 90 million metric tons of carbon dioxide that will come from producing, transporting, and burning all that methane over the 40 to 50 years the pipeline is expected to operate.

Residents along the project’s path joined academics, local organizations, and environmental nonprofits in filing lawsuits, seeking injunctions, and packing hearings. As they worked the legal system, other activists staged equipment lockdowns, organized rallies, and took to the trees for months-long sit-ins. The efforts led to some wins. Opponents repeatedly delayed construction, got various permits thrown out, and leveled allegations of water quality violations and illegal work on national forest land. In late 2018, the 4th U.S. Circuit Court of Appeals issued a series of rulings annulling the pipeline’s access to federal land and striking down a key permit. The next year, the Federal Energy Regulatory Commission ordered an end to almost all construction.

The project languished until the summer of 2022, when Manchin, a key Democratic senate vote who often challenges his party, made his support of Biden’s climate agenda contingent upon the pipeline’s completion. Last summer, he included a provision in the debt ceiling deal that effectively cleared away any remaining hurdles. A short time later, the Supreme Court lifted a stay on construction through a 3.5-mile stretch through Jefferson National Forest. Crews returned to work with renewed vigor.

So too did the protestors. Morning after morning, week after week, pipeline workers clocked in only to find their work impeded. Grannies locked to rocking chairs in the pipeline path, teenagers glued to construction equipment, worksites crowded by 20 to 30 people intent on stopping the day’s progress, more often than not, successfully. The campaign drew college students from nearby Roanoke, neighbors from across the mountains, seasoned organizers and newer activists with little experience, all part of a near decade-long coalition, all activated by the pipeline’s anticipated completion, and many ready to face legal consequences for opposing it.

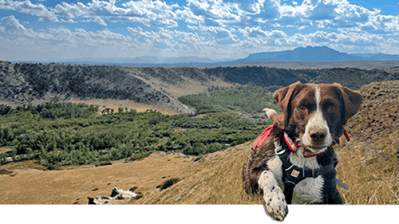

Photo by Katie Myers / Grist

Jammie Hale is a bespectacled and bearded 51-year-old from Giles County, Virginia. Before he joined the campaign to stop the pipeline five and a half years ago, he was depressed and struggling with addiction. It didn’t help that the ruckus of construction invaded his waking and sleeping hours as it got closer and closer to his home, which lies within the 500-foot blast zone that could level his house in an explosion. “After a while, you hear all that, it kind of gets under your skin,” he said with a gentle intensity. “You build these angers up inside you, and how do you release these angers? Through self harm?” He became sleepless, consumed with visions of his family, and the land he plans to deed to his children, going up in flames.

When people began to organize, he and others in the community joined in. He found a will to live in the work. “I’m five years sober because of this project,” Hale said. “Because, you know, I wanted to be useful.”

Hale attended permit hearings, tested water, and, when people started sitting in trees, hiked up the mountain to support them. He brought home-cooked meals, blankets, and supplies, and rallied on the forest floor to boost their morale. “I instantly fell in love with these people because they were just so badass,” Hale said. He and his neighbors began to take more concerted action, filming and peacefully confronting pipeline company surveyors who came unannounced to survey their land for construction. Eventually, he found himself engaging in civil disobedience, fully aware of the risks he faces.

Hale is among a growing number of protesters the Mountain Valley Pipeline company has targeted with injunctions, a potentially costly legal hassle that could lead to jail time for anyone found on a construction site. Local authorities are taking an increasingly dim view of folks like Hale and show little hesitation in pursuing them for even minor infractions as the company continues to seize their land through eminent domain. These days, Hale supports protestors from afar by making signs and sharing food, among other things. There’s still some risk, he says, but if he lands in a cell or a courtroom, so be it.

“I’m not scared,” he said. “It’s kind of strange that they’re trying to get people for trespassing when they are the ones that have been trespassing.”

Another longtime pipeline fighter who goes by Larkin is no stranger to arrests, or to supporting people whose civil disobedience has landed them in court time and again. A soft-spoken health care worker from nearby Blacksburg, Virginia, Larkin, who is in her late 30s, has been fighting resource extraction in Appalachia since she was a teenager. She spent the better part of a decade marching onto dusty strip mines, locking herself to equipment, and demanding a federal ban on mountaintop removal coal mining. Ten years ago, that energy shifted toward the region’s multiplying pipelines. The Atlantic Coast Pipeline was proposed alongside the MVP; it met with similarly vehement opposition, and eventually died amid mounting legal costs and project delays. In short, protest worked, Larkin said.

With the Supreme Court greenlighting the MVP, it seems to Larkin and others that there’s only one thing left to do. That is, throw their bodies upon the gears, in hopes of at least slowing things down for one more day, every day, for as long as possible, by force if nothing else.

“We knew from the get-go that a chapter of the fight requiring an escalated level of resistance is going to come if folks have any hope in pushing back,” Larkin said.

Despite the risks, Larkin, and many others, feel they are taking ownership of their future and their dignity. When we fight, they say, we win, and it’s better that fossil fuel companies know their encroachments won’t go unchallenged. Larkin also feels it will deter future projects like the MVP. Without organized opposition, she feels the whole regulatory system will continue to rubber-stamp permits until the ocean overtakes Washington.

“Old men with no thought to the future are ruining things for all of us,” Larkin said. “It really is down to us to just be mad. And do it with our bodies and be in the way.”

She knows she’s never far from becoming a target of the Mountain Valley Pipeline company’s ire. Over the years, she’s seen friends locked up and beaten down at various protests, and sometimes it makes her feel old. After so long in the fight, her knees and back ache, and she can’t spend hours sitting on the floor painting banners like she used to. When she began this work, she burned herself out quickly, believing that the world would end if she didn’t give everything she had.

“When it’s so obvious that the world is on fire, it does feel like you have to put it out on the table all at once,” she said. “Just like, why think about the future, we have no future, kind of thing. And here we are, eight years later in this fight.”

Yet there are moments, even now, when the pipeline seems inevitable, when she feels the joy of having taken a stand, of having made lifelong friends, of having done the right thing.

“I freaking love to have daybreak on a new blockade that has gone up in the night,” Larkin said, smiling. “And I think the other thing that I love is that I have really met and built real relationships of trust and solidarity with neighbors, people in my community who I wouldn’t have otherwise known.”

The pace is fast and the emotions run hot right now, but the stakes have felt high for a long time, Larkin said. She’s watched friends get sick, both from burnout and from the environmental risks of living near extraction, and watched some die of environmental illnesses and illnesses of stress and poverty. When trying to pinpoint exactly how the fight has lasted so long, Larkin points to the constant influx of new activists, particularly energized young people from nearby towns and colleges, and from other, similar campaigns.

One activist who goes by Gator had only just turned 18 and drifted north after a working-class childhood on the Gulf Coast of Louisiana. He felt disconnected and adrift at a military high school, beset by a gnawing sense of climate apocalypse and a bleak future. “My home is disappearing,” he said bluntly.

Gator found his way to the Weelaunee “Stop Cop City” occupation in Atlanta last summer. The connections he made there led him to the woods of Virginia and West Virginia, where he camped in the pipeline’s path and met people who shared his feelings of desperation and urgency.

He felt himself cross a Rubicon of sorts during a stint in jail after his arrest at another demonstration. He spent several days locked up, not knowing how much time had passed and listening to guards mock the people around him. As he sat there on the cold concrete bed, he knew there was no return to regular life, to regular expectations for himself.

“It used to be that you’d be like, ‘I want to keep my nose clean, because I have a chance of having a career and having, at least for me, and the people I love, a comfortable life,’” Gator said. “But even that is disappearing.”

Photo by Katie Myers / Grist

The atmosphere in Elliston was, like the movement itself, at once nervous and defiant. Like environmental justice advocates most everywhere, those standing up to the Mountain Valley Pipeline are facing ever greater restrictions on their protests and increasingly harsh punishment for their actions.

In September, Mountain Valley Pipeline LLC filed a lawsuit against more than 40 individuals and two organizations — Appalachians Against Pipelines and Rising Tide North America. The suit seeks more than $4 million in damages and a ruling prohibiting the defendants from accessing construction sites, planning demonstrations, or raising funds for protest activities. The company said it decided to sue because protestors endanger themselves and workers, and because they’re breaking the law.

“If opponents were truly interested in environmental protection,” said MVP spokeswoman Natalie Cox, “they would have engaged with us to address their concerns through honest, open dialogue, which we respectfully offered on numerous occasions, rather than wasting agency resources and burdening the courts to support their myopic agendas.” Cox also blamed protesters for disrupting landowners and limiting the region’s economic opportunities.

Such lawsuits — which activists and their attorneys often call a strategic action against public participation — are usually filed by corporate or government entities against people who speak out on a matter of public concern. Those fighting the pipeline say the suit is intended to chill protest and intimidate them. Mountain Valley Pipeline LLC has been regularly adding defendants to the suit, often after identifying them near protests or reading their names in the news. Many protesters have been charged with felonies in recent months, all for blocking construction.

Despite a relative lack of trouble at the Peters Mountain lockdown – authorities arrested two people and quickly released them – the arraignment later that week proved more contentious. The two young activists were unexpectedly re-arrested and prosecutors slapped each of them with a felony kidnapping charge – presumably, protesters say, for asking construction workers to leave their vehicles – and held without bond.

According to Appalachians Against Pipelines, another protester, who goes by Pine, turned themself in on a felony warrant; they were charged with kidnapping and theft for holding up a work vehicle. A judge set bail at $25,000. Another protester was sentenced to six months, with three of them suspended, for similar charges. They are free pending an appeal.

“This system is seeking to doom us to a future that will not even exist,” Pine said in a statement. “However, there is solidarity everywhere … these ridiculous charges that I received do not make me afraid, since I know I do not stand alone.”

Fear of arrest and imprisonment remains a restless undercurrent for many activists, said a young organizer who gave only her first name, Coral. She stepped away from fighting pipelines on tribal land to answer a call for support in central Appalachia..

Photo courtesy Appalachians Against Pipelines

“I’ve been grappling with the repression piece a lot because it is working,” said Coral, who identifies as Indigenous but would not state her affiliation for fear that it might help identify her. For her, and many of those fighting alongside her, the effort to stop the pipeline is a commitment to protecting unceded Indigenous land, and to building a world free from old, colonial, and extractive social structures. That obligation weighs heavily on her, though. The killing of an environmental activist at an ongoing forest blockade in Atlanta and the ceaseless violence against Native land defenders worldwide is never far from her mind. “Our people were persecuted and killed for fighting for our land,” she said.

And yet, despite it all, the pace of protest has increased since construction resumed. Few weeks go by without people locking themselves to equipment, blocking the pipeline route, or picketing banks that support the project and the company building it. Despite several frightening incidents, including one in which crews reportedly felled trees dangerously close to an activist, the blockades and lockdowns continue. The hope, many activists said, is to draw a critical mass of supporters to the region. The fight, they said, is far from over, and they hope to bring the same kind of energy sparked by the massive Dakota Access Pipeline protests.

In Elliston, as the crisp October day warmed, the crowd was as energized and raucous as ever, echoing demands that have evolved over decades of environmental organizing in central Appalachia. Many hands unfurled colorful banners connecting the fight against climate change to movements opposing war, genocide, incarceration, and the theft of Indigenous land. Before long, though, several police cars slowly rolled up the road from the main highway, blocking the group’s exit. As officers stepped from their cars and made their way up the hill, some protesters with children in tow began to worry about their safety but remained for the moment.

As the police amassed, a young person of about 20, bundled in warm clothing and locked to an excavator, called down to the crowd. Their face couldn’t be seen, but their voice sounded small and very young. “I’m here because…these mountains are beautiful,” they called, laughing. “Appalachia is beautiful. This planet is beautiful!” Some in the crowd, though anxious, smiled at the voice speaking for them. The crowd held one another and swayed in the breeze as the drums started up again.

“The judge has had it up to here with y’all,” one exasperated police officer remarked as some in the group talked him down from arresting everyone in sight, mothers and children and all. Other officers took photos of license plates and threatened to increase their retaliation if they saw any of the cars at another protest.

When the group moved on to a neighboring plot owned by someone sympathetic to their cause, the police followed them, threatening to cite anyone who stuck around. Everyone knew that probably meant being added to MVP’s lawsuit. They decided to move along, but vowed to return another day.

This story was originally published by Grist with the headline Inside the last-ditch effort to stop the Mountain Valley Pipeline on Jan 16, 2024.