Human killings of wolves are on the rise in Washington

The wolf population is in decline for the first time since the species returned to the state. In southwestern Washington they’ve been wiped out

Exposed position: The status of wolves in Washington, like these juvenile gray wolves in Mount Rainier National Park, is anything but secure. File photo: Ron Reznick/VWPics via AP Images

By Dawn Stover. May 1, 2025. This year’s report on gray wolves from the Washington Department of Fish and Wildlife had bad news for the species—and for efforts to relax wolf protections.

The number of wolves counted in Washington dropped for the first time since wolves returned to the state in 2008.

The count of successful breeding pairs also declined significantly, despite a slight increase in the number of wolf packs.

Human-caused wolf mortalities have risen significantly over the past several years.

Southwest Washington once again has no known wolves. Three of the four wolves that the wildlife department documented in the region in recent years have been killed illegally, and the fourth wolf has not been seen in more than a year.

Two of those wolves had formed a pair that did not have time to produce any pups before they were killed.

The poachings have cast doubt on the state’s strategy for species recovery, which anticipated that wolves would disperse naturally to the southwestern third of the state and successfully reproduce there.

Since 2008, when the first resident pack was documented in northeast Washington, the number of wolves and wolf packs in the state grew by an average of 20% every year. Until last year.

As of Dec. 31, 2024, the state wildlife agency and the Tribes that manage wolves on tribal lands in the eastern third of Washington counted 230 wolves in 43 packs—of which 18 packs had successful breeding pairs. That total includes an estimate for lone and dispersing wolves that are difficult to count.

The previous year’s count, after correcting for an error in counting wolves on the Confederated Tribes of the Colville Reservation, was 254 wolves in 42 packs and 24 breeding pairs.

The bottom line: Washington’s wolf count dropped by 9% last year, and the number of wolf packs with successful breeding pairs dropped by 25%.

Precarious population

Wildlife populations can fluctuate naturally from year to year. However, wolf advocates point to rising human-caused mortalities as the most likely explanation for the 2024 falloff.

The new count “vindicates the concerns that we’ve voiced about the wolf population and the levels of human-caused mortality,” said Fran Santiago-Ávila, science and conservation director at Washington Wildlife First, a nonprofit group critical of the state’s management of fish and wildlife.

After being shot, one wolf died after dragging itself to a water source without the use of its back legs.

“We’re dealing with a very small and precarious population,” said Santiago-Ávila. “Two hundred and thirty animals isn’t really that much.”

The Washington Department of Fish and Wildlife (WDFW) documented 37 wolf mortalities last year—35 of them were caused by humans.

More than half of those mortalities were wolves legally harvested by tribal hunters from the Colville Reservation in northeastern Washington.

A step backward for species recovery

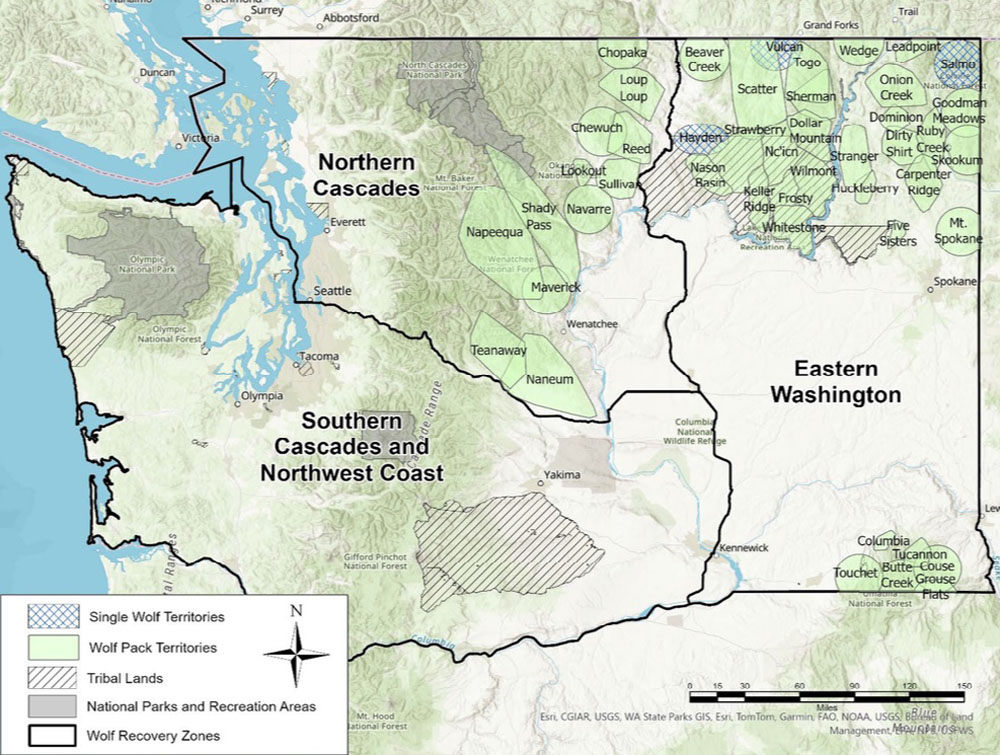

Washington is divided into three wolf recovery regions.

To meet the state’s minimum goals for species recovery, each region needs at least four successful breeding pairs.

Known wolf packs and single wolf territories in Washington as of Dec. 31, 2024, not including unconfirmed or suspected packs or border packs from other states and provinces. Map: WDFW

Wolves from established packs in the state’s eastern and northern regions began dispersing into the southwestern region, known as the Southern Cascades and Northwest Coast, a few years ago. That region’s first resident wolf pack was confirmed two years ago—a male and female that traveled together through the winter and were dubbed the Big Muddy Pack.

However, the female went missing before the pair could start a family. She was not wearing one of the radio collars that wildlife officials use to track wolf movements.

By last fall, her collared partner, as well as two other collared male wolves that dispersed into the region in the past two years, had all been illegally killed.

One of the three collared wolves was found dead in the fall of 2023 in a federally protected wildlife area.

A second wolf was killed near Goldendale, Wash., in late September or early October 2024. According to a press release from the U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service the wolf “died from a gunshot wound that led to its starvation over the course of days or possibly weeks after it dragged itself to a water source without the use of its back legs.”

The third male died northeast of Trout Lake, Wash., in December 2024. That wolf was the only remaining member of the Big Muddy Pack.

All three of the illegal killings occurred in Klickitat County, where Sheriff Bob Songer has stoked anti-wolf sentiment.

The killings left the southwest region of the state without any wolves by the end of 2024.

Rewards but no prosecutions

The U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service and WDFW are investigating the deaths.

In both 2024 cases, the federal government has offered a $10,000 reward for information that leads to an arrest, criminal conviction or civil penalty assessment. The nonprofit organizations Washington Wildlife First, Conservation Northwest and the Center for Biological Diversity have offered an additional $30,000 in reward money.

Rewards rarely lead to convictions, though. In Oregon, cash rewards of more than $130,000 have gone unclaimed.

Oregon’s wolf count rose 14% in 2024. However, as in Washington, poaching and other human-caused mortalities are rising in Oregon.

In Washington, humans were responsible for the deaths of 128 wolves reported in the past four years, compared with 58 in the prior four years. Much of that increase is attributable to legal harvesting by Colville tribal hunters.

Before 2020, the Colville Tribes typically harvested six to eight wolves per year. Since then, the Tribes have allowed more wolf hunting and trapping, taking an average of 19 wolves per year.

Path to delisting

About one in every six of Washington’s wolves lives within the Colville Reservation.

Wildlife advocates are concerned that increased hunting on the reservation, coupled with rising mortality from other human causes including WDFW removals in response to wolf-livestock conflict, is creating vacancies for wolves that would otherwise migrate out of the area.

“With more and more wolves being killed in eastern Washington, this results in fewer wolves available to disperse from their packs and head further west,” according to a Center for Biological Diversity press release about the drop in Washington’s wolf population.

Frozen movement: Depletion of wolf populations in Washington mean fewer wolves migrating to other areas, like this gray wolf captured on a remote camera in Wallowa County, Ore. Photo: WDFW

The state’s recovery plan for gray wolves relies on dispersal to colonize southwest Washington.

But reduced pressure to disperse, and illegal killings of wolves that do disperse, may thwart that plan.

That’s bad news for efforts to remove wolves from the state’s endangered species list.

Last year, WDFW proposed reclassifying wolves throughout the state from “endangered” to “sensitive” status. After the Washington Fish and Wildlife Commission decided to retain the endangered status, state legislators proposed HB 1311, a bill that would require WDFW to manage wolves as a sensitive species.

That bill did not make it out of the House Agriculture and Natural Resources Committee. However, President Donald Trump removed gray wolves from the federal endangered species list during the final months of his first term—a decision that was reversed by a court ruling two years later. It seems likely that he will try again.

If wolves were to be federally delisted, the state of Washington could follow suit.

The post Human killings of wolves are on the rise in Washington appeared first on Columbia Insight.

.jpg?format=1000w)