Healing a Dark Past: The Long Road to Reopening Hospitals in the Rural South

Bridging Access:

Across rural America, communities of color may be facing barriers to health care, but they’re also laying the groundwork for a more equitable future. Whether it’s hospitals reopening, a community’s holistic approach to maternal care, or the grassroots work to bring comprehensive services to immigrants, these stories offer a road map. This story is part of a collaborative reporting effort led by the Institute for Nonprofit News’ Rural News Network, with visual support from CatchLight. Photo credits: Ariel Cobbert and Aallyah Wright.

BROWNSVILLE, Tenn. — On a late evening in 1986, sharp pains hit Alma Jean Thomas-Carney’s stomach like lightning.

Days earlier, she’d just returned home to Brownsville, after dancing all weekend at her high school reunion hundreds of miles away in Illinois. Maybe that’s where the pain originated, she thought.

She cried profusely to her husband to take her to a hospital. But not the local Haywood Park Community Hospital, a 62-bed facility built in 1974.

“Please don’t take me up there. Don’t take me up there,” she pleaded. He rushed her to the car and drove to Jackson, Tennessee, nearly 40 miles away.

When she arrived at the hospital in Jackson, she underwent exploratory surgery. They found cysts on her ovaries, a diagnosis she says she wouldn’t have gotten at Haywood Park.

“I didn’t trust I would get the proper care or care that would help me to survive,” she told Capital B.

Years prior, she experienced an unwelcoming environment from white staffers, including doctors, at Haywood Park. Upon entry, she’d walk to the reception desk, only to be ignored or met with unpleasant looks.

“They acted like you were invisible,” she said. “Whether they were talking or drinking coffee, they kept doing whatever they were doing and didn’t pay attention to you.”

Haywood Park’s reputation deteriorated over the years. Some residents voluntarily drove elsewhere if they could, or went without critical care, which contributed to low patient volume. Many more reasons, such as financial instability, resulted in its ultimate demise.

The hospital closed in 2014, after a long, slow decline. But, the news saddened the community, including Thomas-Carney. “Despite my ill-feelings or experiences I had in that environment … you have indigent people living in Haywood County who need to get to the closest facility available.”

From 1990 to 2020, 334 rural hospitals have closed across 47 states, which disproportionately affect areas with higher populations of Black and Hispanic people. Since 2011, hospital closures have outnumbered new hospital openings. In Brownsville, they’ve been able to do the impossible: reopen a full-service hospital. They’re not the only ones.

Less than three hours away in the heart of the Mississippi Delta, leaders in Marks reopened their facility in 2021, after a five-year shutdown. In neighboring Georgia, county officials received millions in congressional funding to reopen their hospital in Cuthbert, which closed in 2020. Currently, they’re researching what model is feasible for their town.

When a rural hospital closes, there’s usually no turning back. Yet, Brownsville became an outlier two years ago and is part of a growing but short list of hospitals in rural counties that have been able to fully reopen. What’s happening in this 68% Black town of 9,700 people is quite uncommon, health experts say. Usually hospitals cut back or reduce services, such as obstetric departments, to keep their doors open. The most recent alternative to prevent closures include the Rural Emergency Hospital designation, a new model established in 2020 that eliminates in-patient beds but keeps an emergency department in order to receive a boost in federal support. At least 29 rural hospitals have converted to rural emergency hospitals, according to Becker’s Hospital Review.

While this is a fix for some, it may not be the most viable for others, experts say.

“Once you’ve seen one rural community, you’ve seen one rural community; they’re very different. We understand that not every rural hospital that is struggling will benefit or will want to convert to this rural emergency hospital,” said Shannon Wu, senior associate director of payment policy at the American Hospital Association. “We see this as a tool in a toolbox for those that fit their community needs.”

Why the distrust runs deep

Thomas-Carney lost faith in the local health system long before the establishment of Haywood Park 50 years ago.

As a kid, she witnessed her grandmother lying in a hospital bed in the basement of the Haywood County Memorial Hospital, a 30-bed facility built in 1930 during Jim Crow. Steel pipes followed the linings of the walls. The sounds of steam echoed in her ears.

“I just remember looking around, and it didn’t look like nothin’ that I had seen in a book about a hospital,” she explained.

Thomas-Carney’s grandmother’s experience was not uncommon, as most Southern, white-run hospitals refused to accept Black patients. The few that did placed them “on inferior Black wards, often in the basement, and usually with no separation by disease process,” writes historian Karen Kruse Thomas.

Kruse Thomas details how prior to World War II, hospitals in the South were racially separate and Black patients mostly went to all-Black hospitals, if they had one. Few and far between, Black hospitals were unaccredited, underequipped, and struggling to remain open.

In the 1940s, the federal government began to address hospital segregation through the Hospital Survey and Construction Act, known as the Hill-Burton Act. At the time, the South had the highest population of Black folks with the worst rates of morbidity and mortality. In 1938, the surgeon general called the South “the number one health problem in the nation.”

Today, the health disparities can be described the same.

Black people still experience higher rates of disease, chronic illnesses, and mortality in comparison to their urban counterparts. In Tennessee, Haywood County has higher percentages of adult diabetes, obesity, and overall poor health in comparison to the state and national averages.

Unfortunately, where you live dictates your health and the type of access you have.

Only recently did a study in the National Library of Medicine distinctly spell out that structural racism — in addition to poverty, education, and environmental conditions — is a major contributor to why such health disparities continue to persist.

“In rural areas, especially in the South, it is important to understand how institutional policies, such as the Jim Crow laws that segregated hospitals and neighborhoods, led to differences in resource allocation between white populations and nonwhite populations, which may impact healthcare access today,” the study’s authors noted.

Greta Sanders, a Brownsville resident, recalled how Eva Rawls, a Black registered nurse who worked at Haywood County hospital, was forced to work under the supervision of white women who were licensed practical nurses, even though she was the superior.

That hospital closed in 1974, the same year Haywood Park opened.

“When [the new owners] found out that a registered nurse was working underneath the LPNs, they were just blown away,” said Sanders, a retired lab technician who worked at Haywood Park. “When the white LPNs had to start working under her supervision … they did not like it.”

Advocacy for critical and preventive care isn’t enough

Many residents in Brownsville — the birthplace of the Queen of Rock ‘n’ Roll, Tina Turner — have received life-saving care at the local hospital.

One of those people: the wife of John Ashworth, a local civil rights activist and historian who co-runs the Dunbar Carver Museum with Thomas-Carney. Some time ago, Ashworth’s wife got stung by a bee. By the time she arrived at Haywood Park, her blood pressure was extremely high. They immediately admitted her and stabilized her.

“I have mixed emotions, but I really think it was a good hospital,” Ashworth said. “I am absolutely convinced that my wife would not be alive today if that hospital had not been there at the time.”

Ashworth believes some deaths could have been prevented had the hospital been open.

Fed up with the poor health outcomes in his community, William “Bill” Rawls Jr. ran for office. He became the first Black mayor in Brownsville in 2014. Before he could celebrate the win, the hospital closed its doors for good.

So, he thought.

Rawls set out on a mission to work with Michael Banks, a local attorney, and county officials to bring back the hospital. Like many small towns, the train tracks here still represent a divide, a symbol of racial segregation.

While Banks worked to find quality suitors for the hospital, Rawls started the Healthy Moves Initiative, a health education and preventive care effort. He hosted health fairs, quarterly free wellness screenings, built walking trails and a dog park, and created a farmer’s market. But, it didn’t create the impact he’d hoped for.

It’s still a work in progress, he says, but the challenge is getting more participation.

Two years after Brownsville lost its hospital, Marks, a small town in the Mississippi Delta, did, too. The closure of the only critical access hospital in Quitman County resulted in the loss of 100 jobs. Similar to Brownsville, limited health care access resulted in longer waits to receive emergency and medical assistance.

Six months later, the Black town of 1,600 people lost its only grocery store.

During this time, Velma Benson-Wilson returned to her hometown after 20 years in Jackson, Tennessee. It started as frequent trips to conduct research to write What’s In The Water?, a tribute to her mother. She stayed a bit longer to work as a consultant on cultural tourism for the county, particularly the construction of the Amtrak project and memorializing the history of the Mule Train, which kicked off the late Martin Luther King Jr.’s Poor People’s Campaign.

But, the health crisis and food desert in Marks motivated her to dig deeper.

Wilson became the Quitman county administrator, the first Black person and female to serve in the position. After she helped close the Amtrak deal in 2018, she turned her focus to the hospital and worked with the county supervisors to find a solution.

After working to save a hospital in Holly Springs, roughly 90 minutes from Marks, Quinten Whitwell, an attorney from Oxford, and Dr. Kenneth Williams, a Black physician, launched Progressive Health Group to keep rural hospitals from closure across the South.

Five years after the Marks hospital closed in 2016, its Certificate of Need was set to expire. The legal document was required to reopen, establish or construct a health facility.

Whitwell, in quarantine, worked with his team on a plan to get it approved by the state.

Manuel Killebrew, president of the Quitman County Board of Supervisors, said that state Democratic Sen. Robert Jackson passed legislation to help reopen the hospital. Soon after, in 2021, the county supervisors voted to reopen the hospital in partnership with nearby Panola Medical Center in Batesville, Mississippi. The county gave Whitwell’s group a loan, and Citizen Banks of Marks gave a $1 million donation to reopen the facility as Progressive Health of Marks, a critical access hospital. The same year, a local entrepreneur opened a new grocery store across the street from the hospital.

The hospital has a walk-in clinic, emergency room, radiology department, and several other services, such as telehealth, according to Mejilda Spearman, the administrator for the Quitman hospital. They currently have four in-patient beds and are currently renovating their senior care unit. They’ve hired fewer than 50 people. While they’ve seen a steady increase in patients since, they still struggle to get community support.

But, some residents still aren’t satisfied, Killebrew added.

“There’s still people who gripe, but the hospital here is the closest place to get medical treatment,” he said. “If one of their loved ones were shot or had a heart attack, they get here, and at least they’ll survive.”

A Georgia community gets a second chance

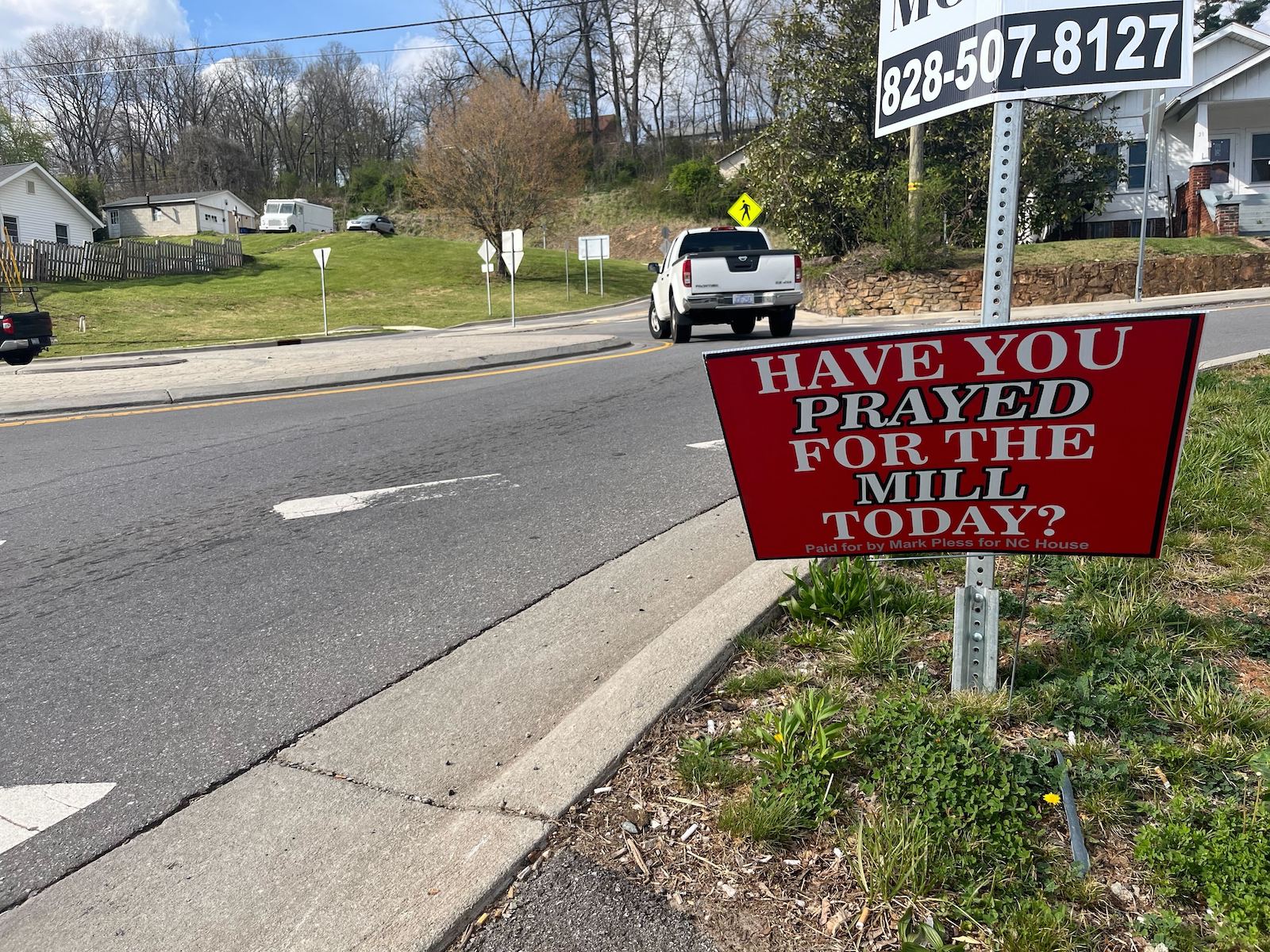

Despite low support in Marks and Brownsville for a hospital, residents in Cuthbert, Georgia, have prayed for more health care options in their predominantly Black community of fewer than 3,100 people.

The Southwest Georgia Regional Hospital in Cuthbert, the county’s only hospital, closed at the height of the COVID-19 pandemic due to increased costs from aging infrastructure and underinsured and uninsured patients. Officials added that the inaction of Medicaid expansion in Georgia also contributed to the closure in Randolph County, which is majority Black.

Before the hospital closed, some uninsured residents relied on the emergency room for primary care. Now for emergencies or other care, many travel 30 minutes to Eufaula, Alabama, or nearly an hour to Albany, Georgia, said Cuthbert Mayor Bobby Jenkins.

Minnie Lewis, a retired educator, travels to Albany and Columbus frequently for appointments and would love to eliminate the additional time it takes for roundtrips there.

“In fact, I just had a health scare, but I had to go to have a CT scan there. Then I had to go to Sylvester [Georgia] to a hospital there because they didn’t have enough space there for me for that particular thing,” she said. “I would have had that CT scan right here in Cuthbert, if it was open.”

When the hospital closed, the doctors left, too. Until about a year ago, the town had no doctors, despite Care Connect, an urgent care clinic, opening immediately after the hospital closed in 2020. Jenkins and residents hope the draw of a hospital will bring more jobs, affordable housing, and food options into the town, which is racially divided.

“With the white there and the Black here, you can’t get nothin’ done. We don’t go to church together, but at least we can have some common ground when it comes to the community and for the betterment of all the citizens,” said Cuthbert council member Sandra Willis.

The hospital is the only issue that they’re united on, she says. The majority Black county commissioners, all-Black city council, and Randolph County Housing Authority have worked together to figure out a solution.

They’ve been able to get the attention of their state and federal officials. After four years, they have a plan.

Earlier this year, U.S. Rep. Sanford Bishop and Sens. John Ossoff and Raphael Warnock requested congressional earmarks to develop and reopen Southwest Regional. They secured more $4 million from the USDA Community Facilities Program and more than $2 million from HUD for the Randolph County Hospital Authority to move forward, according to a spokesperson in Bishop’s office.

There’s no date for when a hospital, or some version of it, will be reopened in Cuthbert. Will critical access, rural emergency hospital, or freestanding emergency department work best? County officials contracted with a third-party to conduct a feasibility study to decide what route to go with the hospital.

“What we hope is to have an emergency room so we can get ‘em stabilized,” State Rep. Gerald Greene said in a phone call. “We’re hoping this is going to work, but we’ll have some [inpatient] rooms. That’s our plan.”

‘True systemic change is a grassroots effort’

In Brownsville, it took six years to find a solution. In attorney Banks’ eyes, it was all “pure luck.”

On a recent tour of the hospital, Banks — who is now CEO of Haywood County Community Hospital — pointed out a bed that displayed colorful LED lights with symbols, advanced technology that checks oxygen levels, weight, and heart rates.

“If a [patient] gets too close to the edge, the alarm goes off. So, the nurse at night – rather than waking someone up – they can come out and look at those lights.”

He credits Braden Health, the hospital management group that took over the hospital. As counsel for Haywood County, Banks would take prospective buyers on “a tour with a flashlight” because the building was boarded up. None of the deals panned out — until 2020 when they met Dr. Beau Braden, an emergency medicine specialist and co-founder of Braden Health. The county officials agreed that Braden Health could take if they improved the property and ran the facility as a full service hospital.

Two years later, they reopened Haywood Park Community Hospital, under a new name: Haywood County Community Hospital. They downsized to nine in-patient rooms and have a staff of 80 employees, all from Brownsville or neighboring communities.

In addition to an emergency room, they have an urgent care walk-in clinic, pharmacy, mammography, ultrasound, and radiology department. Despite the new infrastructure and quality, Banks averages about five patients a day, and about 25 patients in the ER. But, there have been times when they’ve had to send patients to other facilities because they are full, he said.

Residents stop by often for the handprint ceramic tile wall in the main entrance of the hospital. In the 1990s and early 2000s, kids in Brownsville painted these tiles. Many people come back to find their handprint. They built a conference room so local organizations can meet. They also eat at Annie Mae’s Cafe, a soul food restaurant in the hospital named after Tina Turner and run by two local cooks who lost their restaurant during the pandemic.

Banks, the mayor and residents, are optimistic about the hospital’s future. In fact, they’re planning to expand, adding things like a physical therapy section. They expect more traffic, especially with the opening of Ford’s Blue Oval mega facility.

“Ever since we opened the inpatient side, we’re breaking even. We’re profitable and growing more every month,” Banks said. “Even if Brownsville stayed the size it was, we’d be fine.”

Staying on top of the accounting, rural health-related policies and regulations, and making sure insurance providers pay is the key to being sustainable, Banks says.

Beyond federal dollars, there’s a need to expand Medicaid, increase Medicare payments, and incentivize health care professionals to work in rural areas, rural health experts say. They also advocate for health equity, specifically on better pay systems for rural hospitals and ensuring those investments focus on communities that have “faced historical and contemporary challenges of racism.”

Ultimately, everyone has to work together — government officials, local agencies and the residents.

“People are dying. Not because the hospital is there or not there. It’s because we’ve not taken control. We’re accepting a lesser quality of life and a shorter life expectancy,” Rawls said. “True systemic change is a grassroots effort, but you will need people from the top pushing legislation that’s going to allow rural hospitals to survive or reopen.”

The post Healing a Dark Past: The Long Road to Reopening Hospitals in the Rural South appeared first on Capital B News.