Latino families in Nevada are a deciding factor this election cycle

This story was first published in The Fulcrum and republished with permission.

Although Nevada has a sitting U.S. senator who is Latina (Catherine Cortez-Masto), Latino political representation still lags. This could explain why some Latino voters feel discouraged or why — despite such high population numbers — Latino voter turnout is lower than that of other demographics in the state.

A study by the Pew Research Center found that 36.2 million Latinos will be eligible to vote in 2024, up 4 million from the 2020 election. This makes Latino voters one of the most critical voting blocs, leading both Democrats and Republicans to ramp up their efforts to tap into such potential support. In Nevada, Latinos are projected to be crucial in both the presidential race and the contest for the state’s other Senate seat, pitting incumbent Jacky Rosen (D) and against Republican Sam Brown. Ads from both parties populate platforms like YouTube — one of the three most used apps by Hispanics — trying to win over the Latino voter bloc.

What these ads, as well as the political machine, seem to miss is that Latinos are not a monolithic group. This can lead politicians to miss out on the many different factors that shape Latino identities. Voter tendencies can vary significantly between different Latino groups — and even within Latino families.

A multigenerational perspective

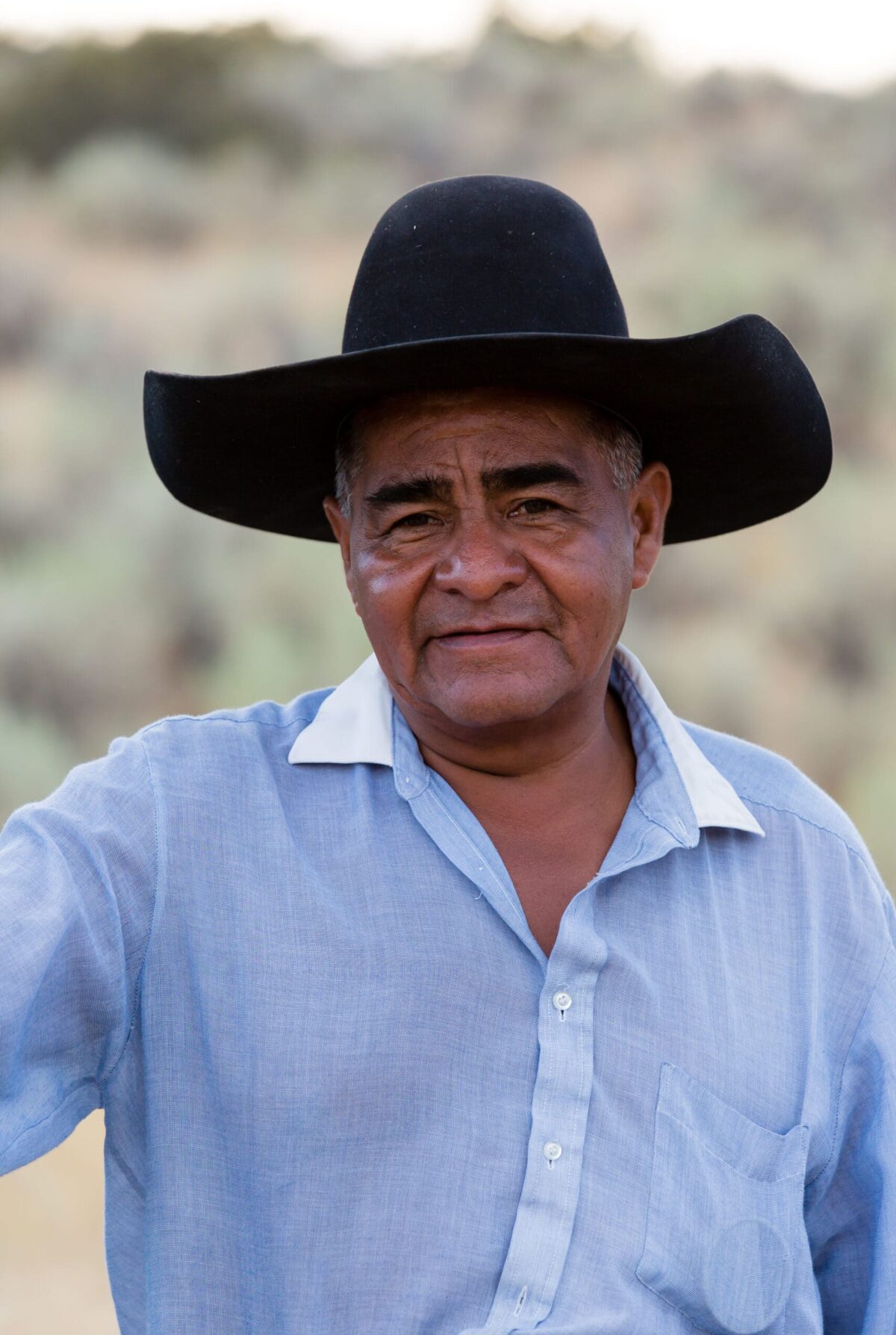

Rico Cortez is a Mexican American living in northern Nevada. He was raised by a single mother, Rebecca Guerrero, and his Latino roots, along with growing up with a strong matriarch, have shaped his political views. “Women’s rights are super important to me because women raised me. Women brought me into this world,” Cortez stated.

Latinos tend to put a larger emphasis on family than that of non-Hispanics. According to the Pew Research Center, 84 percent of Latinos believe that family members are more important than friends. Cortez moved back to northern Nevada five years ago to care for his aging mother because his connection to his family is so important.

Rebecca Guerrero was born in Verdi, Nev., in 1929, making her 95 years old. Despite her age, she is still civically engaged and has consistently voted throughout her lifetime. For her, it was important to pass on this civic duty to her children. Her political identity has shaped Cortez, and today, both Guerrero and Cortez represent a unique part of the Latino vote in Nevada.

As a young mother, Guerrero struggled with the cost of living in Nevada. “Well, it was no picnic. It was rough because the man that I was married to didn’t care too much. And we had to go on welfare to get my kids what they needed,” she remembers. Rising rent prices, inflation and increasing the minimum wage have become increasingly important to Guerrero and her family.

This falls in line with the priorities of other Latinos in Nevada. In the state with the largest Latino middle class, the cost of living is one of the most significant issues for many Latino voters. Eighty-four percent of Latinos in Nevada agree that it is difficult for middle-class families to prosper in the United States. Republicans — like GOP Gov. Joe Lombardo — have capitalized on this by touting their ability to do things like loosen requirements for business licenses in the state and tighten immigration laws to save jobs.

Immigration is another critical issue for Latinos in Nevada, and Guerrero has her own immigration story. At 10 years old, she had to leave her dying grandfather in Durango, Mexico, to travel to live with her aunts in California. Leaving him behind was hard for her. “I had to kneel and have my grandfather do the sign of the cross and bless me. Then I crossed, he stayed on that side, and I came to this side,” she said.

While some Republicans have used immigration as a selling point to Latino voters, the Trump campaign has pushed anti-immigration rhetoric and massive amounts of disinformation, leaving some voters, like Guerrero, upset; when asked about Trump, she stated, “If you don’t have a good president, well, everything goes to pot. If we get Trump, well, Trump is an asswipe.”

According to a Univision poll, Latino voters in Nevada favor Kamala Harris by 18 points. While both Guerrero and Cortez will be voting for Harris in November, 41 percent of Latino voters are undecided. Issues like abortion and border security are making some lean toward the former president.

Abortion is one of the most significant issues for Cortez in this election cycle. He sees reproductive rights as an essential part of supporting women. “I’ve just always been an advocate for women. I don’t want to see my little nieces having to fight for things that my mother already fought for.”

For Guerrero, abortion has been a bit of a gray area. She comes from a strong Catholic background. Catholic doctrine opposes abortion. And with Catholicism being the largest faith amongst Latinos, it can sway values and belief systems. While Guerrero is still very religious, time and conversations with her son eventually led her to support a woman’s right to choose. Cortez and Guerrero are among the 44 percent of Nevadan Latinos who say they will vote “yes” on a ballot measure that would establish the right to abortion in the Nevadan Constitution.

The issue of abortion reflects how Latino viewpoints can differ significantly depending on factors such as age, religion and party affiliation. While the Latino vote will be crucial in Nevada and across the nation in November, it is not monolithic, and many different cultures and life experiences shape the identities and values of Latinos in the Silver State.

Regardless of the differences, Cortez is proud to be Latino and is excited to see how important the Latino vote has become in Nevada. He celebrates the sense of community he feels being Mexican American.

“I love that sense of community. I think we have a strong sense of community, and we care for each other and look after each other.”

Latino families in Nevada are a deciding factor this election cycle was first published in The Fulcrum and republished with permission.

Introducing the Sierra Nevada Ally 2024 Elections Voter Guide

Election Day is fast approaching and there are several offices, candidates and ballot questions that are up for a vote of the people on Nov. 5. To help sift through it all, the Sierra Nevada Ally has created a voting guide with links to campaign sites, social media pages and more information on key dates, ballot questions and races that will affect the everyday lives of people living in the region.

This interactive guide includes information on candidates for federal, state and local offices, with links to campaign websites, social media profiles and more information. Simply scroll through the page to browse information or you can click into specific information and races.

Access the voter guide on your desktop computer, laptop, or mobile device by simply clicking “Voter Guide” on the main navigation on the Sierra Nevada Ally homepage.

This guide was made possible through technical support from GovPack, which is funded by a grant from the Knight Foundation.

What solar panels can tell us about investment in rural Nevada

At Scougal Rubber, a corporation in McCarran, Nev. east of Sparks, machines apply more than 1 million pounds of pressure at 280 degrees Fahrenheit to create giant bearing pads used in buildings and bridges to help transfer weight throughout the entire structure. The company is headquartered in Seattle, but has been at this location since 2011. It recently got a more than $700,000 grant grant from the U.S. Department of Agriculture to install solar panels on the property to cut energy costs and operate more sustainably.

Why here? Why is the federal government investing in this Seattle-based manufacturer? And what does it all have to do with rural development in northern Nevada?

Eva Price has lived in rural America most of her life.

“I am from rural Nevada. I live in Fernley, Nevada. Two years ago, 2021, or now three years now, we moved from California, and I used to live in a rural part of Oroville, California,” she said.

Now, she’s working as the controller at Scougal Rubber Corporation.

“I joined the company a year ago and one month, basically. One year and one month ago.”

In her job, Eva is head of the financial and HR departments.

“I oversee accounts receivable, accounts payable, payroll, HR. Um, I do the general ledger and financial statements with Rob [Scougal President Rob Anderson]. So I report directly to Rob, the president,” she said.

Rob Anderson brought around 11 people with him from Seattle to start Scougal Rubber in 2011. The company now employs about 90 people in northern Nevada. He thinks the grants USDA provides help to the economy of rural Nevada.

“Their ideas, it would be very valuable for this area,” he said. “Um, “Especially if they can get into the residential and multiple family housing and that sort of thing, to bring workers closer to the manufacturing environment.”

For Eva, a resident of rural Nevada, this sort of aid directly benefits employees like herself.

“A grant like this is really very helpful to manufacturing companies like ours, because we never thought we never thought that a grant will be available to us,” she said.

The grant she’s referring to comes from the U.S. Department of Agriculture, or USDA. The agency is giving Scougal Rubber nearly $730,000 to install solar panels to help with electricity costs and reduce the pollution that comes from using fossil fuels. It’s part of a push by the Biden/Harris administration to invest in more clean energy projects, like this one at Scougal Rubber or the large-scale Thacker Pass lithium mine in northern Nevada.

And it’s what brings Basil Gooden to northern Nevada. He’s the undersecretary for the USDA.

“I really enjoy getting out in these communities and seeing the partners, seeing the workforce in rural development, but seeing the people on the ground that actually benefit from our programs and hearing their stories,” Gooden said.

Gooden is fairly new in the job, being sworn in as undersecretary in February. But…

“This is my second stint with USDA Rural Development. I worked previously in the Obama Administration as a State Director,” he said.

To him, this is more than just a job, though.

“Rural is in my blood,” he said. “I went to Virginia Tech as an undergrad. My dad took me to college back in the 80s. When he dropped me off, he told me three things. He told me, ‘Hey, study hard, get good grades, stay out of trouble.’ But the third thing he told me was, ‘Don’t come back to the country because there are no opportunities in the country.’”

This idea has persisted through the 1980s to today. According to the Rural Policy Research Institute, rates of poverty are 3 percentage points higher in rural areas than in urban areas, which can lead many to leave the country for city life. It’s this kind of “rural brain drain” that is forcing Gooden and the Biden/Harris administration to rethink development in rural America.

“I am passionate about making sure that the opportunities are in the country, that we are making sure that rural kids can come back to their areas, because there are either jobs or housing,” Gooden said.

There have been some signs that the federal government is making rural investments a priority. The Bipartisan Infrastructure Bill is investing 3.5 billion in Nevada in 2024 for 275 specific projects, including expanding broadband in rural America.

In that bill, more than $117 million were earmarked for clean energy projects, like the one at Scougal Rubber. Gooden said his role with the USDA is about supporting these efforts.

“We have in rural development an awesome, awesome opportunity to really focus on rural energy,” he said. “This administration, the Biden/Harris administration, has really, really pushed a lot of funding in renewable energy, knowing that it will help reduce the cost of operations for rural businesses, for farmers, ranchers.”

Not everyone is on board, though. Some farmers and ranchers are concerned how these investments could uproot their way of life.

“It’s not as simple as people saying, ‘We don’t want this in our backyard. We don’t want this disturbing us.’ These communities in rural areas of Nevada and throughout the West have suffered immense impacts from historical mining in the area, from Superfund sites to mercury contamination, and they still are greatly impacted by those,” said Susan Frey, a third-generation rancher who lives in Orovada, Nevada.

Frey is the spokesperson for the Thacker Pass Working Group, a collection of residents dedicated to protecting their community against impacts from the Thacker Pass lithium mine that was approved for construction in 2021. Frey said she loves rural Nevada, but federal officials don’t always understand the full impact of rural development on life in these areas.

Take jobs for example. Frey said most people in her community are employed by local farms and ranches, so any new employees would be coming from neighboring cities.

“With that growth comes problems with infrastructure and housing and things like that, that communities have to deal with as these things are coming online,” Frey said.

That’s part of the reason Basil Gooden from the USDA visited northern Nevada. He says he wants to hear directly from rural residents and businesses about the challenges they face and how his agency can help make rural life more vibrant and sustainable.

“One of my favorite quotes comes from Vernon Johns, who is a civil rights leader back in the 1960s. He would always say, ‘If you see a good fight, get in it. If you see an area that is really trying to fight to either level the playing field or fighting for equity, get in it and help them,’” Gooden said.

For people like Eva Price, that means being able to work in the rural areas they grew up in, which is pretty unique.

“We have deer that are coming through our property as well, in the neighborhood where I live. Here, we see horses a lot. They have the right of way, so we have to stop when they cross the street,” Price said, laughing.

Rodeo riders of all ages and skill buck, bash and bust in Fallon

John Wayne once said, “Courage is being scared to death but saddling up anyway.” Courage was on full display at last month’s 10th annual De Golyer Bucking Horse & Bull Bash Rodeo in Fallon, Nev.

The affordable, family-friendly event happens every year on the last Saturday of June. If you didn’t get a chance to see all the action in person this year, the Sierra Nevada Ally has you covered.

For many participants in this year’s event, rodeo is more than just a sport; it’s a way of life.

Every year, Kristina and Cody de Golyer host the Bucking Horse & Bull Bash Rodeo at the Fallon Fairgrounds in Fallon, Nev. Rodeo goers got to enjoy Mutton Bustin’, Jr. Steer, Bull Riding and Barrel Racing events, among many others. This year, the rodeo had the honor in welcoming back the International Trick Riders.

This year’s event was not only a big milestone for the de Golyers, who were celebrating the tenth year of the rodeo. It was also 4-year-old Storm Jackson from the Shoshone Nation’s first attempt at Mutton Bustin’.

“It was fun!” he said, as he got some help putting his cowboy hat back on his head.

Another young participant who was excited to ride the Jr. Steers was Justin Sherman. The 13-year-old has been riding for a year-and-a-half, and had taken part in ten rodeos. He is inspired by his uncle who also participates in Professional Bull Riders (PBR) rodeos.

For 16-year-old Ray Valdez, it’s all about riding colts. He’s been riding for two years, thinking he would start riding bulls. But after his first rodeo, he instead got hooked on riding colts.

“I love the feeling being up there, when they jump, and I am up in the air. It’s a great feeling,” he said.

The annual de Golyer Bucking Horse and Bull Bash happens every June. So if you’re looking for a rodeo event without the large crowds found at the Reno Rodeo, this trip to Fallon might just be the way to go.

You’re at least guaranteed to see some courageous riders of all ages.

On the Chopping Block

Thundering equipment, pulverized terrain littered with the dismembered and dying. D-Day? Mariupol? Game of Thrones? No, it’s a sunny day in the American West, and a pair of Bureau of Land Management bulldozers are ripping pinyon and juniper trees out of the ground. To do this, they’re dragging a 20,000-pound Navy anchor chain across the forested landscape.

The Bureau of Land Management, or BLM, is the powerful Interior Department agency that administers 245 million publicly owned acres, or one-tenth of the nation’s land, as well as 700 million acres of subsurface mineral rights. It describes its mission as sustaining “the health, diversity and productivity of public lands for the use and enjoyment of present and future generations.”

In pursuit of this lofty goal, the BLM has obliterated pinyon-juniper forests since the 1950s, “chaining” millions of acres throughout the West. The agency’s fire program tells Barn Raiser that over just seven recent years—2017 through 2023—it removed more than 1.7 million acres’ worth of trees. In doing that, the agency spent just over $151 million in taxpayer money on chaining and on followup activities intended to encourage replacement plants. The BLM calls the latter “treatments,” a mild-sounding term that encompasses harrowing, plowing, mowing, fire, herbicides and more. Eventually, 38.5 million acres of pinyon-juniper forest will be on the chopping block, says the BLM.

Next up are 380,000 acres of eastern Nevada’s ecologically rich pinyon-juniper forest in South Spring and Hamlin Valleys, near Great Basin National Park. To save the forest, the Center for Biological Diversity and Western Watersheds Project have brought a federal lawsuit against the Bureau of Land Management as a whole, two of its local Nevada offices and its parent agency, the Department of the Interior. Nevada’s United States District Court is expected to hear arguments in the suit this fall.

Western Shoshone elder and systems engineer Rick Spilsbury, who joined the litigation, called the BLM’s plan “ecocide” and “a scorched earth attack on … the natural world that has supported my people for tens of thousands of years.” The Western Watersheds Project describes the BLM plan as “heavy-handed,” with “woefully inadequate” analysis to back it up. The high cost is no surprise, says Scott Lake, attorney for the environmental nonprofits. “The government is hiring contractors who are running heavy equipment for hours a day and weeks at a time.”

The BLM calls the suit the result of a “policy disagreement” rather than a matter of law. The agency has justified the practice of chaining with reasons that have morphed over the years, claiming, for example, that the ancient indigenous pinyon-juniper forests are “encroaching” into grasslands, thereby posing a wildfire hazard as well as a risk to the habitats of native species.

Others say that the BLM’s justifications are based on bad science and incomplete analysis. A 2019 review of more than 200 scientific studies by wildlife biologist Allison Jones and colleagues found that “what we see today in many cases is simply [pinyon and juniper trees] recolonizing places where they were dominant but then chained.” The recolonization “is mistaken for encroachment,” wrote Jones et al. The scientists concluded with a warning: “The pace of activity on the ground may be outstripping our understanding of the long-term effects of these treatments and our ability to plan better restoration projects.”

Checking what boxes?

The BLM must consult with tribal nations when projects affect their interests. The agency says it respects “the ties that native and traditional communities have to the land” and the way “strong communication is fundamental to a constructive relationship.” According to the agency, “This means going beyond just checking the box to say we talked to Tribal Nations when we take actions that may affect Native American communities.”

As an example of that “strong communication,” the BLM’s Environmental Assessment for the chaining project describes the agency mailing letters describing it to 5 out of 21 Nevada tribes, along with one in Utah. The document then reveals the agency has had no back-and-forth communication with any of them.

This anemic form of consultation “has been happening for years,” says Western Shoshone elder and healer Reggie Sope from Duck Valley Indian Reservation, which straddles Nevada and Idaho. “That’s the way they put it. ‘We sent them letters, that was our consultation.’ ” His tribe was among the 16 in Nevada that were not consulted, according to the list in the BLM’s Environmental Assessment.

Nor was the Te-Moak Tribe of Western Shoshone Indians, a four-Band consortium headquartered in Elko, Nevada. Putting a letter in the post is not consultation, says Julius Holley, a council member of both the Te-Moak Tribe and one of its constituents, the Battle Mountain Band. “In our opinion, consultation is a face-to-face meeting,” he says.

The Te-Moak Tribe gets some 40 letters a week from the BLM, Holley says. These may involve matters ranging from minor, such as a mining company’s discovery of an isolated flake (a chip knocked off a piece of stone while creating an arrowhead or other tool), to major, like chaining 380,000 acres. The council continually goes through the letters to determine the important ones, Holley says, then asks for tours and/or meetings concerning them. Citing the ongoing lawsuit, the BLM did not answer questions about how the contacted tribes were chosen and whether any actual interaction had taken place since the Environmental Assessment was written.

Ancient knowledge undercuts BLM claims

The BLM’s crusade against the pinyon-juniper forests recalls the decimation of the continent’s great buffalo herds and salmon runs, undertaken in the 1800s to cripple the tribes that relied on them. For millennia, the pinyon-juniper forests have been vital to tribal nations in Nevada and other Western states. They shelter myriad animal and plant species and are the source of pine nuts—a sweet, creamy, protein- and nutrient-rich staple that was once a mainstay of tribal diets and traditions.

When rabbitbrush in Nevada’s lower elevations turns yellow in the fall, tribal members know the nuts are ripe. It’s time to trek to the mountains and harvest them. While some use long poles to knock the pinecones off the trees, others engage in an age-old tribal fire-prevention practice: removing and chopping up fallen timber and brush that could act as tinder and feed a wildfire.

The cut wood is put to use roasting the cones and making meals for the group. The roasted pine nuts are removed from the cones and eaten out of hand or stored for future use. Ground up, cooked pine nuts are used in preparations ranging from bread to porridge to soup. They can be formed into patties with berries and ground meat—usually venison or elk, says Sope: “Like a quick snack but all natural. Very delicious and nutritious.”

When Sope was a boy, he says, he learned from his elders that long ago the Creator guided his people to a place where they would find all the food and medicine plants they’d need. “So here we remained,” Sope says. “We survived for a long time. They had ceremonies and blessings to honor the Root Nation and ensure it would be plentiful for generations to come.”

The BLM creates a serious challenge to that abundance. After its bulldozers have demolished South Spring and Hamlin Valleys, the agency plans to “treat” whatever’s left. This involves choosing among fire, herbicides and other alternatives. The agency calls this process “adaptive management,” which seems to imply benign creativity. The BLM’s court documents also instruct Nevada’s U.S. District Court to be “highly deferential” to this type of decision-making.

Not so fast, says Lake, the environmental groups’ attorney. He notes that federal courts have repeatedly directed agencies to provide site-specific, landscape-level analysis for immediate and indirect effects of such actions before moving forward. Broad guesswork and ongoing improvisation are not enough, federal courts have held. The National Environmental Protection Act specifically requires this, so it’s not just common sense, but a matter of law, argues Lake.

The BLM’s continually changing assortment of reasons for razing the trees started in the 1950s with the need to create additional grazing land for cattle. That reason has become less acceptable though, according to Lake. “The idea that we should be deforesting [to provide] cattle forage is not really that popular these days, so the rationales have been shifting.” Creating livestock range hasn’t stopped; it’s just no longer widely acknowledged.

Citing the ongoing lawsuit, the BLM did not respond to questions about its past and present goals of creating grazing land. The agency does, however, still support grazing; it offers livestock grazing permits at less than $1.50 per animal per month on 155 million of its managed public acres.

For the birds

One new BLM reason for deforestation that sounds ecologically benevolent is creating habitat for the sage-grouse, an increasingly scarce bird—and in the process demolishing the habitats of many more animal and plant species. “You have to look at the whole picture before you draw up a plan,” chides Sope.

Further, the shrubs in which the sage-grouse likes to breed, nest, forage and over-winter may take decades to establish themselves in devastated terrain. During that time, the BLM has to fend off competing weeds with fire, mowing, herbicides and other destructive methods.

One wonders how any birds will cope. The BLM’s Environmental Assessment assures us that leveling a forest is a “negligible” issue for migratory birds. While the chaining is underway, they simply fly away, the document says; when the noise is over and the forest is gone, the birds will “likely return.”

“To what?” asks Sope.

Meanwhile, tree-dwelling bats are on their own. Under the law, the BLM claims, it need only “consider” effects on them. In preparing the BLM’s court document, someone looked up “consider” in the dictionary and discovered it means “reflect on.” The BLM, according to the document, will contemplate the fate of the bats as it uproots trees, sets fires and applies herbicide.

Fire prevention is another BLM goal. We can all understand that eliminating a forest means it can’t catch fire. However, the extensive surface disturbance the bulldozers create while razing the trees has long encouraged vast swaths of highly flammable, fiercely invasive cheatgrass to spread throughout the West. Overgrazing, motorized recreation and mining have contributed to the spread of the invasive grass, unintentionally imported from Europe in the 1800s as a contaminant of straw packing material and other plant items, according to the US Geological Survey.

As a result, fires that historically occurred centuries apart in the pinyon-juniper forests, cared for by attentive tribal citizens, are now far more frequent. The BLM decries this frequency but does not acknowledge its own culpability for it. Nor does the agency appear to be pursuing multifaceted, systemic and continuously monitored remedies. Simply laying waste to the environment here and there is not supported by science, federal law or tradition.

“The Root Nation is in jeopardy,” warns Sope. “How long are we going to suffer? How long is the Earth Mother going to suffer?”

The post On the Chopping Block appeared first on Barn Raiser.

Colorado River Water Use in Three States Drops to 40-Year Low

Changes in Child Tax Credit Would Have Outsized Impact on Rural Children

This story was originally published in the Daily Yonder here.

The families of more than a quarter of all children living in rural America would benefit from a proposed expansion of the Child Tax Credit that has passed the U.S. House of Representatives and is now under consideration in the Senate.

The expansion would change the credit’s eligibility criteria to include low-income families who don’t get the full tax credit per child because they don’t pay enough taxes to qualify. The current credit phases in until family earnings reach a certain threshold. Most low-income families – usually ones who make under $40,000 annually – receive partial or no credit.

“Because of that structure, it particularly disadvantages children who live in rural areas largely because pay is typically lower in rural areas,” said Stephanie Hingtgen, research analyst at the Center on Budget and Policy Priorities. “Clearly this is upside down.”

Under the proposed legislation, more than 80% of the children who don’t get the full credit would see a boost in their family’s income from the credit, according to Hingtgen. The legislation would also increase the credit slightly, from $2,000 to $2,100 per child.

A study from a Harvard University research center found that when families are given a higher child tax credit – as they were in 2021 during the temporary Covid-19 pandemic relief effort – depression and anxiety rates among parents were lower, possibly because of reduced financial worries.

An estimated 27% of all rural children would benefit from the proposed expansion, compared to 22% in metropolitan areas, according to Center on Budget and Policy Priorities data.

The benefits could be even larger for rural families of color, who on average earn less than white families. In rural areas, 46% of Black children, 39% of Latino children, and 37% of American Indian and Alaskan Native children would receive more money under the Child Tax Credit expansion. For each demographic group, a significantly higher proportion of children from rural areas would benefit than children from urban areas, the analysis showed.

Last week, the House of Representatives passed the legislation in a rare bipartisan vote. Now the Child Tax Credit expansion is being considered by the Senate. If passed, the change would go into effect for the current tax filing season (2023) and continue for three years, ending after the 2025 filing season.

“This is Congress’ only shot this year to pass legislation that would substantially boost the incomes of millions of children and families with low incomes and substantially lower child poverty,” Hingtgen said.

This article first appeared on The Daily Yonder and is republished here under a Creative Commons license.![]()

A Native voting ecosystem in Nevada

Pauly Denetclaw

ICT

The Yamba Shoshone Tribe is located in rural Nevada, mostly dirt roads that make it challenging for some citizens to drop off their mail-in ballots. In 2022, the solution was unusual but it worked for the Yamba Shoshone.

“They’re not just in the middle of Nevada, but I mean it’s complete dirt roads to get there,” said Stacey Montooth, executive director for the Nevada Indian Commission.

Tribal representatives went on horseback to collect completed ballots and drive them an hour to the county seat in Austin, Nevada.

Since 2016, the Native American vote in Nevada has become stronger and stronger. Nonprofit organizations, state and tribal governments have worked together over nearly the last decade to increase the power of the Native vote. The solutions Nevada groups have found to increase civic engagement for rural and urban Native voters is direct engagement, meeting people where they’re at and ultimately, and multiple choices for how to cast a ballot.

There are 20 federally recognized tribal nations that predate the state of Nevada and still live within, what are now, the boundaries of the state. More than 62,000 Native Americans from over 200 different nations live in urban areas.

American Indian, Alaska Native, Native Hawaiian, and Pacific Islanders make up 5.1 percent of the state’s population, according to the U.S. Census. All together the number of Indigenous voters in the state is 158,322.

To put this into context, Nevada’s ninth most populous city, Sparks, has a population of 108,025. The state’s eight most populous area, Paradise, has a population of 191,238. Both are located next to either Las Vegas or Reno.

The journey to increase voter engagement started in 2016 when three Native American veterans and two tribes sued the state of Nevada for violating the Voting Rights Act of 1965.

Some citizens of Pyramid Lake Paiute Tribe and Walker River Paiute Tribe were forced to drive at most 96 miles round trip to access in-person voter registration and in-person early voting. On election day, Pyramid Lake Paiute citizens had to drive 32 miles round trip according to court documents. All this effort because there were no on-reservation polling locations or in-person voter registration.

“My elderly grandma who lived on the reservation all her life. She was having to drive 90 minutes to vote and as she got older, she had to find someone to help her get to the polling station,” Montooth said.

In comparison, some of the affluent residents of Lake Tahoe, on the Nevada side, could walk to their polling locations. On the east shore of Lake Tahoe, in Glenbrook, Nevada, the median sale price for homes, in 2021, was $2.17 million according to a Reno Gazette Journal article.

The court sided with the plaintiffs and required Washoe County to establish satellite polling locations on Pyramid Lake Paiute and Walker River Paiute lands ahead of the 2016 general election.

Since then, Native leaders and citizens have taken it upon themselves to increase voter engagement in innovative ways.

“The one solution for Indian Country is actually multiple choices because there isn’t one size fits all,” Montooth, Walker River Paiute Tribe, told ICT.

There are a number of things the state of Nevada has done to make voting easier, including same-day voter registration, and expanding the use of the Effective Absentee System for Elections, created to make voting easy for Nevada military personnel deployed overseas. Tribal citizens who live on their sovereign lands are now eligible to use this system and vote from the comfort of their homes.

The state also created an opt-out system instead of an opt-in system to get voting services on sovereign lands. Before they had to apply to request these services. Presently, every county is automatically required to work with tribal nations to establish voting services every election.

Tribal IDs can now be used to register to vote. If they meet the state requirements of a photo, issue, and expiration date.

Other solutions that tribes have implemented especially for elders, is utilizing community health representatives.

“They’re trusted voices. They go into these people’s houses on a regular basis, and so it just works perfectly,” Montooth said. “Folks complete their ballot, then you give it to the (community health representative) and (they) can drop it off in that conveniently located Dropbox as they’re heading back to the clinic.”

The Duckwater Shoshone Tribe has many Shoshone language speakers and they worked with the county and state to provide language interpreters for those casting their ballots.

In 2022, for the first time Nevada Indian Commissioner Tammy Tiger and executive director Montooth were invited to a post-election debrief hosted by the Secretary of State. County clerks and county registers from all 16 counties are invited to attend.

“We were representatives of Native America. We got invited and it was really historic, but on the other hand, it just seems so logical and simple. It’s crazy that it took all this time,” Montooth said.

Tiger represented urban Native voters and Montooth represented rural Native voters.

The wins in Nevada, while expedited over the last eight years, build upon the work of many generations of Native people who fought for their right to vote. One that was granted 100 years ago but that wasn’t really available until the passage of the Voting Rights Act. Up to the 60s, Native voters were being denied their right to vote on lands they’ve managed since before this country was even a thought.

“I don’t have words for it because I think about what a change it’s been in our community in just a couple of generations,” said Taylor Patterson, executive director for Native Voters Alliance Nevada. “I think about my grandparents and the spaces that they never had access to.”

Building civic engagement has led to monumental wins in the sagebrush state for Native people.

There is one Native American elected to the Nevada Assembly, Shea Backus, Cherokee. The state has passed legislation to codify the Indian Child Welfare Act and require local police to take reports of missing Indigenous people regardless of jurisdiction as well as upload that information to the National Crime Information Center and National Missing and Unidentified Persons databases.

“During the redistricting process, it was the first time that tribes really got a seat at that table and that we were able to lobby and ask, ‘Why is Walker River Paiute Tribe in two assembly districts and two state senate districts, and two congressional districts?” said Patterson, Bishop Paiute Tribe. “And also talk to Walker River about why that matters.”

Looking toward the future, there has also been a push to increase Native poll workers. Reno-Sparks Indian Colony has a volunteer election committee that runs the tribal elections. During state and federal elections, this committee goes as a group to train in Washoe County to be poll workers for their nation.

“It just makes such a big difference when you go to vote, to see someone that looks like you,” Montooth said. “Better yet, (someone) you know, it just improves the experience so much.”

Commissioner Tiger, Choctaw Nation and Muscogee Nation descendant, was a poll worker at the Moapa Band of Paiutes voting location during the primary election a couple weeks ago. She drove three hours roundtrip, waking up at 4 a.m., to get the polling location set up by 7 a.m. to welcome voters.

Tiger was borned and raised in the Las Vegas metropolitan area and describes herself as an urban Native.

“I know some urban Natives came from down in southern Nevada to work, I went to work the Moapa polls. Some folks went all the way up to Reno, and this is how we envision this statewide,” Tiger said. “How do we work together to support one another and make sure that all of our people have access to voting?”

One way to increase voter turnout would be to make election day a holiday, Montooth said.

Another resource needed for urban Native voters, especially in the Las Vegas metro, is a nonpartisan voter guide that just lays out the facts for each candidate.

“We’ve got 20 judges on a ballot, and so it’s like, what are these trusted sources that are really going through and doing candidate questionnaires and collecting information so you have a more informed vote?” Tiger asked.

For Patterson, it’s increasing the number of Indigenous people elected to city, county and state office. The state needs 61 elected Native American, Alaska Native or Native Hawaiian people elected to gain representative parity, according to Advance Native Political Leadership. They currently have one, Nevada Assembly member Shea Backus.

“We do not have the Native candidates that are representing us and so it was a really big deal to us to make sure that Shea got elected and we were really putting as much energy as we could behind her,” Patterson said.

Born in 1917, Flora Greene, Pyramid Lake Paiute, wasn’t considered a citizen of the United States. When she was 7 years old, the Indian Citizenship Act was passed that would theoretically allow her to vote at 18. She didn’t cast her first ballot until she was 99 years old.

“There had always been something that had come up,” Montooth said.

In 2016, after litigation made the county provide on-site voting for her nation, Greene cast her first ballot in the general election.

“When you think about 90-year-old people who couldn’t go in the front of restaurants in downtown Fallon, or couldn’t use certain public transportation, and they just… they’re so tenacious that Ms. Flora was able to let all that go. And on the one occasion where we’re all equal, I mean she had a little extra pep in her step because she was doing it on her land,” Montooth said.

That was the only presidential election Greene voted in before she passed away in 2018.

Our stories are worth telling. Our stories are worth sharing. Our stories are worth your support. Contribute $5 or $10 today to help ICT carry out its critical mission. Sign up for ICT’s free newsletter.

Tribes face uphill battle to defend sacred land against lithium mining

The coming electric battery revolution in America will require billions upon billions of gallons of water to mine lithium – and many of the new U.S. mines will be located in the drought-prone American West. An investigative report from the Howard Center at Arizona State University. Find more stories from the project here and here.

Noel Lyn Smith and Pacey Smith-Garcia

Howard Center for Investigative Journalism

OROVADA, Nev. – Myron Smart remembers stories told by his father and other tribal elders about the connection between Thacker Pass in Nevada, where a new lithium mine is under construction, and a tragic moment for the Fort McDermitt Paiute and Shoshone.

In Northern Nevada near the Oregon border, Thacker Pass was traditionally used by Smart’s ancestors to camp, hunt and gather, collect obsidian and medicine, and perform ceremonies. On Sept. 12, 1865, the 1st Nevada Cavalry raided a campsite and slaughtered at least 31 Paiutes.

“The cowboys came to kill everybody – woman, children, all the elders,” Smart said last September to a group gathered at Thacker Pass on the anniversary of the massacre. The deadly encounter was an episode in the Snake Wars, one of many skirmishes with Native Americans in the 19th century West, as white settlers came looking to mine for gold.

Now, Smart said, a new kind of mining threatens to wipe out culturally important sites related to the massacre, harming the tribes yet again. Lithium Nevada Corporation, a subsidiary of Canada-based Lithium Americas, will blast through rock and dirt in the area as the company builds a massive, open-pit lithium mine. The federal Bureau of Land Management issued a Record of Decision to greenlight the mine in January 2021. All court challenges to the decision have failed.

The Biden administration has set an ambitious goal for electric vehicles that has prompted a major push for U.S. supplies of lithium and other critical minerals. The Thacker Pass mine owners have courted support from the Energy Department, which is considering a record-breaking, billion dollar loan to the project, and from General Motors, which has pledged $650 million in capital investment, the largest ever by an automaker in battery raw materials. The mine is projected to supply enough lithium each year to produce batteries for one million GM electric vehicles.

Indigenous communities are on the frontlines of a push to create new, domestic sources for lithium. The U.S. has only one active lithium mine, at Silver Peak in Nevada. With a wave of new applicants, that will not remain the case for long. An analysis by the Howard Center for Investigative Journalism at Arizona State University found nine proposed lithium mines are within 10 miles of Native American reservations.

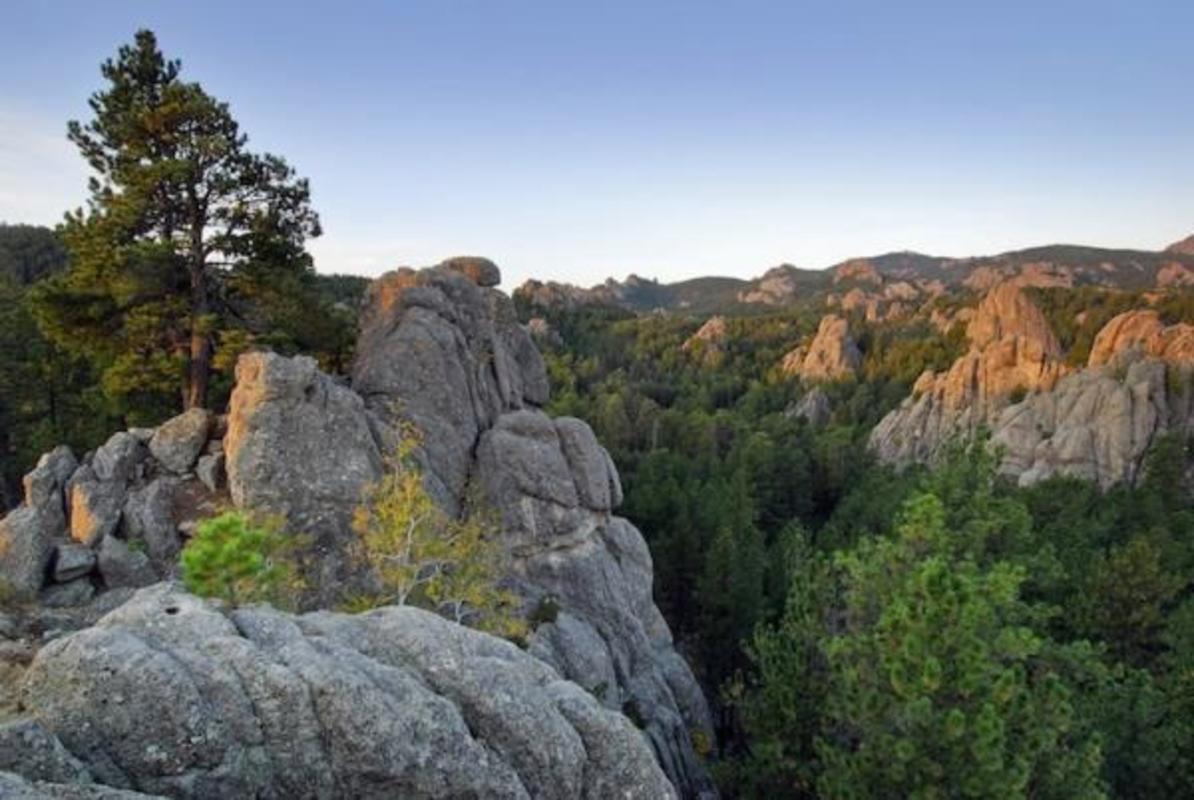

Besides Thacker Pass, lithium mines are also planned near the Black Hills in South Dakota – which the Lakota and nearly a dozen other tribes claim as their ancestral land. Exploration drilling for a mine in Arizona is occurring 700 feet from sacred springs used by the Hualapai people. In a months-long investigation, the Howard Center found lithium mines use vast amounts of water to extract the critical mineral needed for lithium-ion batteries.

Rules exist on paper that sound as if tribes have protections. Federal agencies are required to consult with tribal governments before making decisions that impact their communities, including on mining development projects. However, Valerie Grussing, Executive Director of the National Association of Tribal Historic Preservation Officers, calls tribal consultation a “check-box exercise.”

“Even if they’re able to document their tribal consultation efforts to anyone’s satisfaction,” Grussing said, the federal agency leaders “can still make whatever decision they want.”

Grussing’s claim was confirmed in Congressional testimony by a senior official with the Department of Interior. U.S. Rep. Betty McCollum (D-Minn.) asked the official at the May 2022 hearing if it were true that “BLM has few options under current law to deny a proposed mine – even if that mine was on land, say, sacred to Native American tribes.”

“Under the mining law, if there’s a discovery of a valuable mineral, there is a right to mine. So there can’t be a complete shutdown of a mining operation,” replied Steve Feldgus, who has since been promoted to run the Interior Department’s Land and Minerals Management program. There is no exception for land held sacred by Native American tribes.

Michon Eben, cultural resources manager for the Reno Sparks Indian Colony, agreed. Her tribe wasn’t consulted on the Thacker Pass lithium mine, even though its members consider Thacker Pass ancestral land. “The American government can allow mining corporations to destroy our lands out here, and especially our sacred sites, especially from the lands that were stolen.”

Lithium Nevada denied it will harm the massacre site, and BLM said the massacre site is on private land that isn’t under its jurisdiction.

Grussing said the experience of tribal communities at Thacker Pass is merely a continuation of harmful colonial processes.

“It’s retraumatizing that now this particular place of not just importance, but of massacre, is going to be lost.”

The process of greenlighting Thacker Pass

Federal records show that BLM attempted to consult with three tribes – Fort McDermitt Paiute and Shoshone Tribe, Summit Lake Paiute Tribe, and Winnemucca Indian Colony – all with reservations in the same county as the Thacker Pass mine. BLM said that these tribes were invited to consult “due to their proximity to the project area.”

None responded the following year, and in January 2021, BLM’s Winnemucca District Office issued its Record of Decision greenlighting Lithium Nevada to mine for lithium at Thacker Pass.

Randi Lone Eagle, chairwoman of Summit Lake, said in an email to the Howard Center that she has no record of receiving BLM’s tribal consultation invitation dated mid-December 2019, when tribal offices start to close for the holidays. A few weeks later, Lone Eagle said she came “under tremendous pressure to navigate the COVID-19 pandemic.”

“If government agencies are serious about fulfilling their trust responsibilities,” Lone Eagle wrote in the email, “they will do more than simply send letters; they will call us directly and visit us to speak face-to-face.”

“Sending a letter to a tribe and receiving no response does not constitute sufficient effort to initiate tribal consultation. And so that’s all they did,” said Eben, the tribal preservation officer for Reno Sparks Indian Colony. The federally recognized tribe in Washoe County has just over 1,100 members of Paiute, Shoshone and Washoe ancestry.

“Just because regional tribes have been isolated and forced on to [sic] reservations relatively far away from Thacker Pass does not mean these regional tribes do not possess cultural connections to the Pass,” said Eben of Reno Sparks.

She contended that BLM should have invited tribal consultation for Thacker Pass with all of the Paiute and Shoshone tribes, before issuing the mine’s permits. That includes Reno Sparks.

“They should have consulted with the Reno Sparks Indian Colony because we have members that descend from Paiute and Shoshone.”

Eben wrote a letter to BLM in June 2021 that identified a dozen tribes that have “powerful historical connections to Thacker Pass,” where “some of our ancestors were massacred.”

“The American government was engaged in a campaign to massacre us,” she said in an interview with the Howard Center. “They were sanctioned to massacre us over here because they saw this land and all the minerals that were here.”

She likened opening a mine here to “disturbing Pearl Harbor or Arlington National Cemetery,” noting U.S. memorials to lost soldiers are venerated by the public and not subject to desecration.

In response, after the mine was approved, BLM acknowledged the massacre took place and invited members of Reno Sparks in July 2022 to consult on “indirect areas of potential effects” near the mine. BLM agreed to review approximately 100 acres of BLM-managed land abutting the mine site that had previously not been surveyed. The National Historic Preservation Act’s tribal consultation guidelines allow for a post-review discovery process to ensure that federal agencies “make reasonable efforts to avoid, minimize or mitigate adverse effects.”

For Grussing, “mitigation means loss.”

“If avoidance is off the table by the time we’re at the table, the process is broken. And that so frequently what we see happening with these consultation processes,” said Grussing.

“There’s no consequences. That’s what it comes down to.”

Problems with tribal consultation

BLM issued its Record of Decision to approve Thacker Pass on January 15, 2021, in the last days of the Trump administration.

Eleven days later, Joe Biden, the newly elected president, issued a memorandum highlighting the importance of federal agencies engaging in meaningful consultation with tribes on projects that impact their communities.

The president issued a follow-up memorandum in November 2022, announcing his desire to develop a uniform process for federal agencies to follow for consultation with tribes. That process would require federal agencies to “strive for consensus with Tribes or a mutually desired outcome. Consultation should generally include both Federal and Tribal officials with decision-making authority regarding the proposed policy that has Tribal implications,” the memorandum said.

Yet Grussing, head of the National Association of Tribal Historic Preservation Officers (NATHPO), said she doesn’t think the administration is going to do anything different.

“They’re going on the record and they’re making an investment in various levels, prioritizing Indigenous knowledge in federal decision making and lots of things like that. But when the rubber meets the road, we’re not seeing it put into practice at places like Thacker Pass.”

Grussing said that one of the challenges is the lack of Indigenous knowledge and experience within federal agencies.

“There’s practically zero requirements or standards and even accountability,” Grussing said. Federal agencies retain full discretion over the content of their decisions and don’t need to meet a prescribed outcome, according to the National Historic Preservation Act.

NATHPO is a nonprofit membership association that advocates for protecting sites that perpetuate Native identity and culture. Its main advocacy priority is funding for tribal preservation officers, who serve as liaisons with federal agencies on the management of tribal historic properties.

Chairwoman Lone Eagle of the Summit Lake Paiute Tribe does double duty as the tribal preservation officer for her tribe.

“We get dozens of letters, by mail, from government agencies about proposed projects every month,” she said.

Reno Sparks’ tribal preservation officer, Michon Eben, echoed these concerns. “I’m getting projects from up all over and I’m one person. And so for me, I almost have to pick and choose,” she explained. “Tribes need help.”

She said she hopes that tribes can receive more federal funding to better tackle what is sent to them, “so that we are equipped and educated and have resources to help us to respond to all these letters.”

Grussing added that without more resources, tribal preservation officers will be unable to carry out their duties successfully.

Is Thacker Pass on sacred land?

One of the most contentious aspects of the Thacker Pass project has been the location of the 1865 massacre.

The BLM’s Record of Decision greenlighting the lithium mine at Thacker Pass did not mention the 1865 massacre. That omission, the tribes contend in their 2023 lawsuit, violates the National Historic Preservation Act, Federal Land Policy and Management Act, and National Environmental Protection Act.

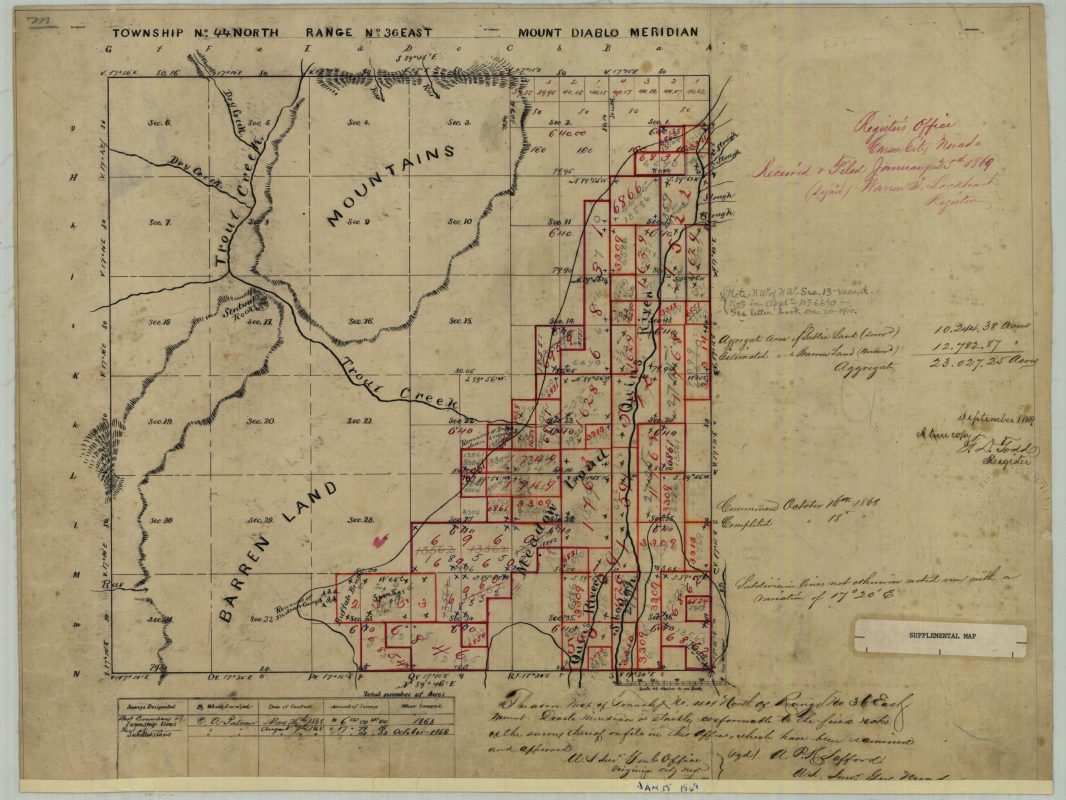

But the Howard Center found at least two records from the BLM’s own archives that show the site of the massacre – a map and a hand-written field journal, both prepared in 1868 by U.S. Deputy Surveyor General Abel Abed Palmer – which depict that the massacre occurred at the mine’s site.

Palmer’s field notes describe finding the “remains of an extensive Indian camp,” which he explains was the site of the 1865 massacre. He also lists seeing “many Indian skulls and remains.”

He notes within the map and his field journal the camp’s location between two specific sections of land near the Trout Creek, a waterway that also runs through the Thacker Pass lithium project site.

Comparing the 1868 map created by the BLM and the map from Lithium Nevada’s Environmental Impact Statement, the Howard Center found that the massacre site appears to fall within BLM jurisdiction and within the area of potential area of effect.

BLM maintains that the massacre site is in fact on private land outside of their jurisdiction. In an email from the BLM Winnemucca office to the Howard Center in December, Spokesperson Heather O’Hanlon wrote that “the location of this site is on Private ground and not within the project footprint.”

Lithium Nevada also backed up this claim. “Ten times this issue has come up in front of a judicial system and 10 times it’s been dismissed,” said Tim Crowley, vice president of government and community affairs. Crowley said lawsuits and attempts to win an injunction by ranchers, tribes and environmental groups have all failed.

In an interview with the Howard Center, Eben from Reno Sparks disagreed that the massacre site only includes the Paiute camp location documented by Palmer. “That’s where it began,” she said about the massacre, but people were killed for miles outside of the campsite.

“Our people did not come out of their huts and just die right there. They ran – because it lasted for several hours,” she said.

Even with the post-review consultation process underway, Eben feels like saving Thacker Pass is a lost cause.

“No matter how much I participate, how much I consult, how much I put in writing, how much I’m at the table – sometimes it’s just not enough. It’s not enough.”

Last ditch efforts

Reno Sparks, Burns Paiute and Summit Lake Paiute filed a lawsuit in February 2023 in the U.S. District Court of Nevada against local BLM officials and Secretary of the Interior Deb Haaland. Among the tribes’ allegations was that the BLM did not make a reasonable and good faith effort to identify historic properties in Thacker Pass or consult the appropriate tribes, as required by the National Historic Preservation Act.

While these efforts were pending, a federal judge said construction on the mine and supporting facilities at Thacker Pass could start in March 2023.

In December, the judge dismissed the lawsuit. In a virtual press conference held by Reno Sparks Indian Colony, former chairman Arlan Melendez said, “We lost the lawsuit because the law favors mining, especially in this state.”

Melendez also announced that they would not appeal the court’s decision to allow construction of the mine to continue. “By the time you would get through to appeal, they would have already desecrated all of the sacred sites. So there’s no sense trying to do that,” he said.

Reno Sparks attorney Will Falk also spoke at the press event on Zoom.

“We all have to make sacrifices to fight climate change,” said Falk about the national push to quit fossil fuels and transition to green energy at the December 2023 press conference. “What they mean is that Native peoples, again, have to sacrifice their culture, their ancestral homelands, so that someone can make a lot of money extracting lithium.”

Reno Sparks and Summit Lake Paiute tribes also asked Interior Secretary Haaland and the National Register coordinator to determine the eligibility of the 1865 massacre site and Thacker Pass for the National Register of Historic Places.

They submitted their request to BLM’s Humboldt Field Office and Winnemucca District Office, the Advisory Council on Historic Preservation and the Nevada State Historic Preservation Office. In a January 2024 email to the Howard Center, BLM said it is still in consultation with the tribes on these sites and has not yet forwarded a nomination to the National Park Service, where the official list of America’s historic places is kept.

Time for reform?

In September 2023 the Biden administration’s interagency working group on mining reform submitted a report with recommendations to revise the laws around mining on public lands.

The report found that the rules are clearer for consultation with tribes when minerals are developed on their present-day reservation lands. But it also noted that tribes have far fewer rights to land outside their present-day borders to which they may hold historical, cultural and spiritual ties.

The report said that it is of “utmost important [sic]” to make clear the procedures for conducting effective consultation and coordination with tribes. New rules must also be implemented to protect sacred, cultural or historical sites, so that some areas are considered off limits for hard rock mining. “Tribes should have more control over sacred lands,” the report said.

The report also proposed ways to create that control, such as developing stronger requirements for tribal consultation on mineral exploration and development projects, “including where the proposed action is within a Tribe’s ancestral homeland even if it is not proximate to the Tribe’s current reservation.”

The report also recommended that the federal government establish mandatory procedures and outcomes for tribal consultation, and tribes be given extra time and resources to participate meaningfully.

Tribal consultation should require federal authorities to meet and share information with potentially impacted tribes as early as possible. “Early engagement with and consideration of impacts on Indigenous Peoples is widely accepted to be an industry best practice,” the report explains.

In May, Rep. Raúl Grijalva (D-Ariz.) proposed legislation to reform U.S. mining law on public land that seeks to codify Pres. Biden’s recent memorandum on creating uniform standards for tribal consultation. He doubled down at the start of Native American Heritage month in November, proposing two more House bills that would strengthen tribal roles in managing public land and protect Native American cultural sites. As of late January, none of the bills has advanced to committees for further review and discussion.

Community benefits

The mining reform report recommended that mining companies negotiate community benefits agreements with impacted tribes.

One tribe impacted by the Thacker Pass mine did negotiate an agreement with Lithium Nevada.

The Fort McDermitt Paiute and Shoshone Tribe signed a Community Benefits Agreement with the company in October 2022. The Fort McDermitt reservation is approximately 26 miles northeast of Thacker Pass, near the state line of Nevada and Oregon.

Crowley said the agreement is the culmination of more than 10 years of dialogue with the tribe. The mining operation will provide employment opportunities for tribal members and people who live on lands that surround the mine, he said.

The agreement provides for job training and construction of an 8,000 square foot community center that will have a daycare, preschool, playground, cultural facility and greenhouse where plants can be grown for use in traditional medicine practices.

“It’s a very isolated area that has very limited opportunity for not just a job, but a job that pays twice the state salary average,” Crowley said.

“It’s an agreement that is the foundation for a really healthy relationship going forward.”

Lithium Nevada declined to provide a copy of the community agreement contract, citing that it is a private document.

In early December, the Biden administration issued a progress report on its work with Tribal Nations. The White House report said that 12 federal agencies are on track to updating their consultation policies. Nine agencies – including the Interior Department – had revised Tribal Consultation policies or developed trainings for federal staff who work with tribes or on policies with Tribal implications.

Grussing of the National Tribal Historic Preservation Officers association is skeptical. In 2007 the U.S. voted against the Declaration of the Rights of Indigenous Peoples in the UN General Assembly, which advanced the free, prior and informed consent (FPIC) standard. The standard upholds Indigenous Peoples’ rights to do more than consult on a project – FPIC ensures that tribes either give or withhold their consent on a project impacting their communities. In 2016 the U.S. ratified the declaration but called its support “aspirational” and “not legally binding.”

According to Grussing, until the U.S. adopts the FPIC standard, tribal consultation is “kind of meaningless. And I don’t see that happening,” Grussing said.

Emma Peterson and Caitlin Thompson contributed to this story. It was produced at the Howard Center for Investigative Journalism at Arizona State University’s Walter Cronkite School of Journalism and Mass Communication, an initiative of the Scripps Howard Fund in honor of the late news industry executive and pioneer Roy W. Howard. For more see https://azpbs.org/lithium. Contact us at howardcenter@asu.edu or on X @HowardCenterASU.