Poll: Support for state’s abortion law weakens

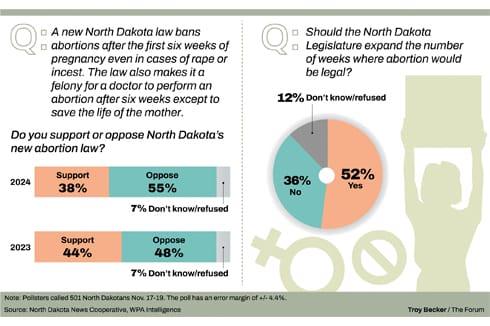

Republicans in North Dakota appear to be souring on the state’s 2023 law banning abortion, a new poll indicates. Only 54% of Republicans support the law now compared to 71% who supported it one year ago.

The poll, commissioned by the North Dakota News Cooperative, also shows overall support has slipped. Total support among adults in the state now stands at 38%. A majority are now opposed to the law at 55%.

In NDNC polling done last November, 44% supported the ban and 48% opposed.

The law, passed by the legislature and signed by Gov. Doug Burgum in April 2023, is currently in legal limbo and awaiting a ruling by the North Dakota Supreme Court. South Central Judicial District Court Judge Bruce Romanick struck down the law in September, arguing it infringed on medical freedoms and is unconstitutionally vague.

The ban had made abortion illegal in all cases, with exceptions for cases of rape or incest – but only when a pregnancy is under six weeks – or when a pregnancy posed a significant risk to a mother’s life.

Violations of the law by health professionals include potential penalties of up to five years in prison and a fine of up to $10,000.

On Nov. 21, North Dakota solicitor general Phil Axt called for the state’s Supreme Court to reinstate the law until the final determination is made.

There are currently no clinics providing abortions in North Dakota. Red River Women’s Clinic, previously based in Fargo, moved to Moorhead, Minn., in 2022 after Roe v. Wade was overturned by the U.S. Supreme Court.

In 2023, state legislators strongly supported the ban, with the Senate voting 42-5 and the House voting 76-14 in favor of the law banning abortion in the state.

The new poll also shows support for an expansion that would provide a number of weeks where abortion would be legal. A total of 52% believe the number of weeks should be expanded while 36% say it should not be.

Overall, only 28% of surveyed adults strongly support the state’s abortion law and 45% strongly oppose it, according to the poll.

The North Dakota Poll surveyed 500 adults between Nov. 17-19, and has a margin of error of +/- 4.4%. The poll surveyed roughly equal numbers of men and women, as well as equally from the eastern and western halves of the state.

The North Dakota News Cooperative is a nonprofit news organization providing reliable and independent reporting on issues and events that impact the lives of North Dakotans. The organization increases the public’s access to quality journalism and advances news literacy across the state. For more information about NDNC or to make a charitable contribution, please visit newscoopnd.org. Send comments, suggestions or tips to michael@newscoopnd.org. Follow us on Twitter: https://twitter.com/NDNewsCoop.

State looks to boost access for youth with severe mental health challenges

Throughout her 25 years as a school social worker, Michelle Vollan can’t recall a period when the number of acute youth mental health situations requiring hospitalization was as high as it was post-Covid.

Vollan has seen anxiety issues increasing, and along with that, attendance concerns and drops in grades for those affected. On the most severe end of the spectrum, thoughts of suicide and self harm have increased leading to cases of psychiatric hospitalization.

And while a spike two years ago which led to 25 psychiatric hospitalizations at the Bismarck middle school she works at has leveled off, she said, the overall situation remains a concern.

“I think, just from my experience, it’s drastically increased,” Vollan said, adding that hospitalizations have halved in the current school year. “However, I think there are as many kids that are suffering with anxiety, depression, that inability to cope … those numbers have not dropped.”

Schools were never meant to be the front line for addressing youth mental health challenges, but that’s what they’ve often become.

“North Dakota has a mental health crisis that we’re in the midst of, and our state is legally obligated to serve children that would have what they call serious emotional disorders or disturbance,” said Carlotta McCleary, executive director of the North Dakota Federation of Families for Children’s Mental Health.

McCleary said around 18,000 youth in the state are in need of treatment for severe mental health issues, but few are getting the full support they need with continuous ongoing services.

According to numbers her organization gathered through open records requests, only 73 youth were treated through the state’s human service centers two years ago. Those numbers jumped to 966 during the 2023-2024 fiscal year, but are still far away from really meeting the population’s needs.

“We’re serving so few kids,” McCleary said. “Where does that pressure go? It goes to our schools.”

McCleary also said the number of youth dealing with severe anxiety has increased, which leads to snowballing impacts with attendance and grades to more acute situations.

“We know that the kids who attend school do better. Their outcomes are better. If they can be at school, on time and attend and not have attendance issues, their outcomes are better,” McCleary said. “Kids with anxiety have a great deal of difficulty, sometimes going to school and getting to school on time because of the anxiety.”

Left untreated, some youth brush up against the juvenile justice system and later, the adult criminal justice system. According to the most recent figures from the Division of Juvenile Services, 74% of the youth coming through the system have issues with mental health.

System-wide approaches

Two programs currently being rolled out across the state could begin addressing gaps in access, however, McCleary said. This includes a $3 million federal grant for implementing a System of Care system for youth from birth to 21 years of age in two regions of the state as well as a program for transitioning all clinics in the state to become Certified Community Behavioral Health Clinics (CCBHCs).

“I do believe it’s going to make a difference,” Vollan said of the programs.

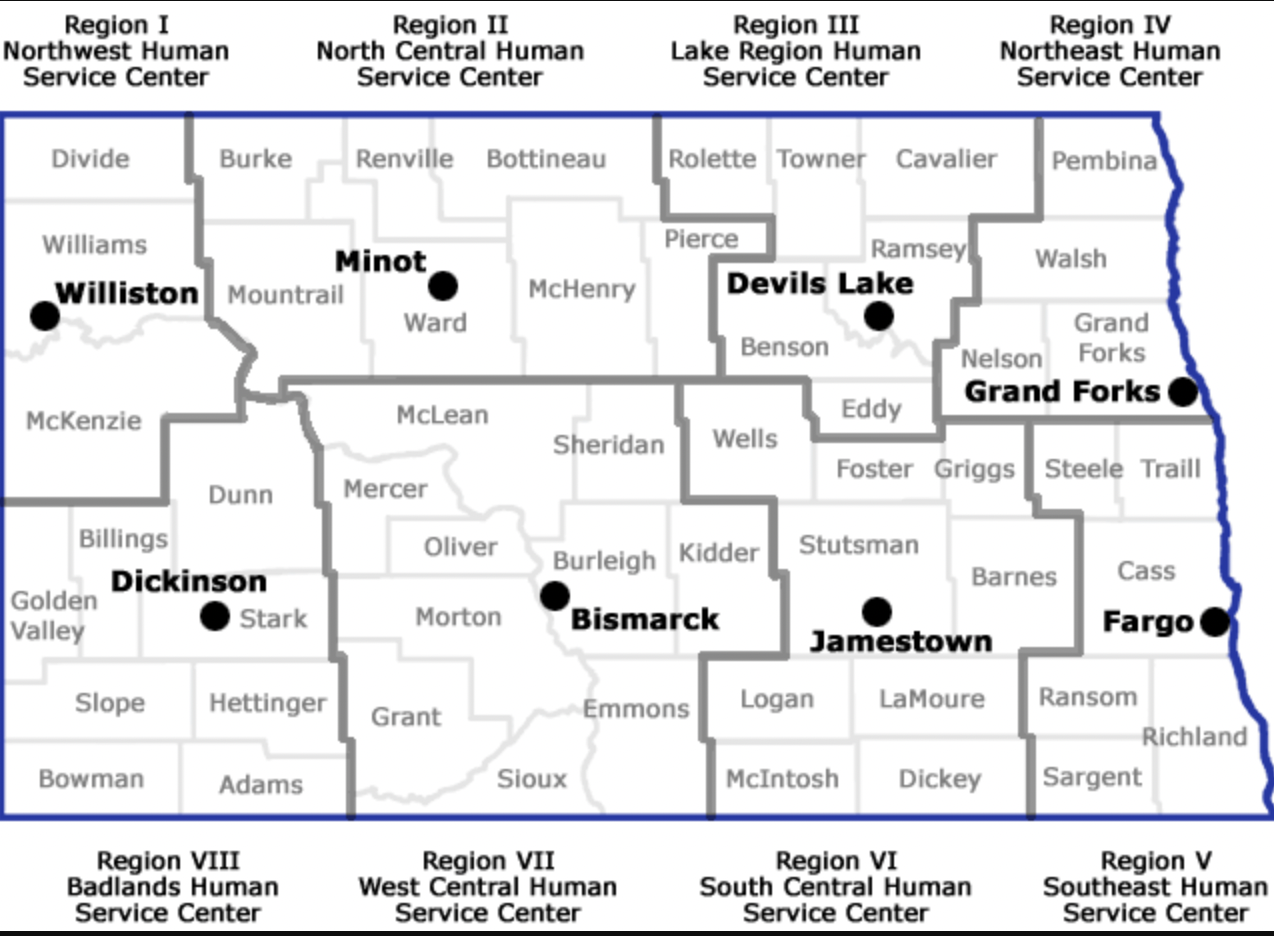

System of Care is being put into place in the Lake Region Human Service Center around Devils Lake, which includes both the Spirit Lake and Turtle Mountain reservations, and in the West Central Human Service Center centered on Bismarck and including the MHA Nation and parts of Standing Rock reservations.

Implementing this stems from a 2018 behavioral health study ordered by the legislature to research strengths and gaps in youth behavioral health services, said Katie Houle, clinical administrator in the behavioral health division at the Department of Health and Human Services (DHHS).

System of Care is a set of philosophies and values, said Houle, that streamline and coordinate care for individuals and families dealing with mental health challenges by breaking down barriers between services preventing adequate care.

Too often youth with a mental health crisis can feel like a “hot potato,” Houle said, “being sent to different places and spaces and not feeling they are getting the services they need.”

Schools, inpatient and outpatient therapists, the juvenile justice system all have their own ways of addressing and interacting with youth, so anchoring them all in a system wide approach that includes the wider family and community is essential to building a better service climate, she said.

“It’s really going to take strategic planning and partnerships across juvenile justice, child welfare, schools, both public and private behavioral health services, and most importantly, thinking about how we work with our family organizations and youth that have these issues,” Houle said.

The second program being developed, and part of a longer term process, has been to identify clinics to begin transitioning to CCBHCs in the state with a goal to eventually transition all eight regions to this certification, said Daniel Cramer, clinical director of behavioral health clinics at DHHS.

North Central Human Service Center in Minot was the first site identified to actively work towards CCBHC status, Cramer said. Northwest Human Service Center in Williston and Badlands Human Service Center in Dickinson are now additionally working towards becoming a CCBHC.

Cramer said this involves prioritizing care coordination and includes hiring behavioral health liaisons at each clinic to establish key relationships with community partners, as well as care coordinators to provide targeted care management.

Certified clinics would be required to have crisis services available 24/7, develop comprehensive services so individuals do not have to coordinate this themselves through a variety of providers, and to assist those in need in navigating the variety of care they need.

“That’s what we’re all moving towards,” Cramer said. “How we can open our door more broadly for those in need, and then assure that when the need is sought out and or identified, that we’re working with all of our partners to build up to meet that need.”

Bringing back wraparound

Vollan said the state system for addressing mental health issues had a broader framework called “wraparound” where it seemed easier to identify what needs and options were available not only for youth in a mental health crisis but also their wider family.

That approach fell away over time and treatments and options have become increasingly siloed.

“When we did wraparound, like back in the day, it truly was this is your team, how do we talk through what supports not only our kids needs, but our parents, the siblings, all of those other pieces that you look at,” Vollan said. “It just left a lot of our families with the question, what do we do? Where do we go when my child is having a crisis?”

Houle said the DHHS has developed a contract with the National Wraparound Implementation Center to assess where North Dakota’s system is at and how it could be reintroduced. This includes specific measures on engaging with families and developing cross system plans where one person is holding each member of the team – wrapping around a child – responsible.

“A lot of parents and caregivers of children with complex needs are burnt out, experiencing really severe caregiver stress, all of those types of things,” Houle said. This could include engaging mentors, faith communities, coaches and other relatives to provide an embrace of support.

“In an ideal system I feel like wraparound and other types of care coordination will work alongside clinical treatment services to make sure the right children are getting into the right place at the right time,” Houle said.

Other wider systems of support could also include meeting underlying issues of instability and stress including addressing poverty, lack of access to transportation, as well as food and housing insecurity, Houle said.

The North Dakota News Cooperative is a nonprofit news organization providing reliable and independent reporting on issues and events that impact the lives of North Dakotans. The organization increases the public’s access to quality journalism and advances news literacy across the state. For more information about NDNC or to make a charitable contribution, please visit newscoopnd.org. Send comments, suggestions or tips to michael@newscoopnd.org. Follow us on Twitter: https://twitter.com/NDNewsCoop.

Three Affiliated Tribes emergency responders combat 11,000-acre Bear Den Fire

Community support has been overwhelming as the Three Affiliated Tribes battle round-the-clock to contain wildfires raging across northwest North Dakota.

One of at least six outbreaks over the weekend, the Bear Den Fire near Mandaree remains 20% contained at time of publication. As of early afternoon more than 11,000 acres were actively burning, including significant portions of the Fort Berthold Indian Reservation.

The fire has burned more than 28,000 acres since it began early Saturday, according to the North Dakota Forest Service. They said a priority on Monday was controlling the fires with air support from the National Guard Black Hawk helicopters.

The Bear Den Fire destroyed two residences and multiple structures but caused no injuries, according to authorities. The Mandan, Hidatsa and Arikara Nation’s Emergency Operations Center lifted mandatory evacuation orders for residents of both Four Bears and West reservation segments by Sunday afternoon.

Authorities said a fire located near Ray killed one man, 26-year-old Johannes Nicolaas Van Eeden of South Africa, and left another in critical condition.

As crews continue battling blazes that began in the early morning hours on Saturday, community members are ensuring hot meals, toiletries and other supplies are available to those coming off long shifts or residents affected by the fires.

Rancher Howard Fettig was on fire watch near Bear Den Bay when he spoke to Buffalo’s Fire in the late morning on Monday. It’s been “neighbors helping neighbors, both on and off reservation,” he said.

“I think it’s an eye-opener.”

Howard Fettig, rancher helping create fire guards north of Mandaree

MHA Nation’s Emergency Operations Center in New Town is requesting donated snacks, coffee, toiletries, and bottled water. Community members at the Emergency Response building in Mandaree welcome donations of brown paper bags to make sack lunches, toilet paper, paper towels, hand soap, kitchen trash bags, coffee, bath towels, and laundry soap.

Lyda Spotted Bear told Buffalo’s Fire the support staff and fire fighters have been very thankful for the consistent supply of hot meals as they rotate through shifts. A steady flow of local volunteers is providing supplies and delivery, Spotted Bear said.

The fire’s path missed Fettig’s home by just half a mile, razing fences, trees and the pasture where he had planned to graze animals this fall.

The crisis was nowhere over, he said, as Monday’s southern winds were making flare-ups’ path unpredictable.

He was one of many farmers and ranchers standing by with tractors to create fire lines – stretches of tilled soil stopping the spread of flames.

“I think it’s an eye-opener,” Fettig said. He hopes people understand it will happen again and “we need to have a better understanding on how to protect people.” Western North Dakota is in moderate to severe drought with no relief of dry conditions in the near future.

The Bear Den Fire drew a coordinated response from the tribes, U.S. Bureau of Indian Affairs, North Dakota Forest Service, Department of Emergency Services, Army National Guard and Highway Patrol.

Dry conditions and high northwest winds – with gusts recorded over 75 miles per hour – pushed fires southeast on Saturday. The exact cause of the fires remains unknown.

Elkhorn Fire, which has burned more than 20,000 acres south of Watford City, was 20% contained Monday afternoon, with no reported injuries or destroyed residences.

By Sunday evening, emergency responders had almost entirely contained a fire near Arnegard and another by Charlson, the Garrison Fire near Emmet and two fires that merged between Ray and Tioga. Downed power lines have left more than 300 without electricity statewide.

The post Three Affiliated Tribes emergency responders combat 11,000-acre Bear Den Fire appeared first on Buffalo’s Fire.

We need more Native American restaurants

This article was produced in collaboration with Eater. It may not be reproduced without express permission from FERN. If you are interested in republishing or reposting this article, please contact info@thefern.org.

If you stop at a roadside restaurant anywhere between North Dakota and Oklahoma, you might not immediately get a sense of culinary diversity. Many menus in rural and small-town middle America consist of high-calorie burgers and processed Caesar salads, along with a few trending items like Buffalo cauliflower or flatbreads. Of course, the region does include diverse cuisines, but you have to seek them out, and even those restaurants often depend on ingredients from massive food suppliers such as Sysco that tend to homogenize flavors.

The middle of the country’s reputation for bland food completely ignores our Indigenous peoples. Within this core of America, dismissed by some as “flyover states,” lies a rich tapestry of culinary heritages. The states of Oklahoma, Nebraska, Kansas, Missouri, Arkansas, the Dakotas, and Iowa are home to 58 federally recognized tribes, each with unique food traditions, including the amazing agricultural heritage of the Mandan, Arikara, and Hidatsa; the bison-centered foodways of the Plains tribes like the Lakota and Cheyenne; and the many cuisines of tribes forced into modern-day Oklahoma after Andrew Jackson’s racist Indian Removal Act.

As a member of the Oglala Lakota from Pine Ridge, South Dakota, a chef, and a historian, I see the massive potential in harnessing, cultivating, and elevating the Indigenous culinary creativity that permeates this massive region. A broad, Native-led restaurant industry could become a huge driver of food-focused tourism. I imagine a world where we could travel across this terrain, stopping at Indigenous-focused restaurants representing the many tribes, and experiencing the true flavors of the area.

In Nebraska, travelers could taste heirloom hominy made with Ponca corn, sage grouse with wild onions, or venison with prickly pear. In the Dakotas and the Great Plains, they might find smoked venison with the rich Lakota chokecherry sauce called wojapi, or antelope with nopales and rosehips. In Oklahoma, Cherokee cooks could whip up grape dumpling soup with stewed rabbit and bergamot-fried onion with turkey eggs and plums for those passing through. These restaurants, with menus rooted in game dishes, heirloom seeds, and wild plants, would fit within a broader Native movement that acknowledges the contributions of Indigenous peoples, educates the public, transcends colonial borders, and promotes understanding about the biodiversity existing alongside cultures.

There’s a long way to go before this dream can become a reality. Many non-Native diners, if they think of Indigenous food at all, can only conjure up fry bread, a survival food taught to us by the U.S. military. Unfortunately, this food, made with commodity ingredients provided by the U.S. government such as white flour and lard, has also contributed to the high rates of diabetes and heart disease that our people have historically suffered. Though fry bread is now an inextricable chapter of our foodways, it should in no way be considered the full story. Other Indigenous culinary identities have been buried, just as Native stories and art are distorted through non-Native gift shops, galleries, and even museums.

Moreover, Native communities are largely economically cut out from other parts of the tourism industry, which brings in billions of dollars a year to each heartland state. This is especially true for national and state parks, lands that Native communities have stewarded for countless generations (despite some attempts at co-management and small economic programs to funnel money to tribes). In South Dakota, for instance, Black Hills National Forest and Mount Rushmore attracted 3.6 million tourists in 2021, but the poverty rate on the nearby Pine Ridge Reservation is 53 percent. Pine Ridge, like all reservations, is still segregated, with scarce economic opportunities. As Native residents struggle to find any kind of economic peace and survive in food deserts off government-supplied rations and junk food from gas stations, they also continue the fight for their ancestral spaces.

At the same time, the tourism industry could be a powerful tool for change — and this renaissance is already happening, if slowly. Native chefs and food entrepreneurs are working hard to showcase their cultures and reclaim their narratives, one dish at a time. Native-owned restaurants are proving that they’re not just relics of the past preserving traditional dishes, but living, evolving blueprints that continue to nourish and sustain their communities economically, as well as nutritionally, culturally, and environmentally.

Take, for instance, the work of chef Nico Albert Williams at Burning Cedar, a catering and education nonprofit project out of Tulsa, Oklahoma. At pop-up dinners, Williams offers menus with contemporary dishes like seed-crusted venison chops, smoky cedar-braised brown beans, venison and hominy stew, and Cherokee bean bread. It’s just one of several operations, including 2024 James Beard semifinalist Natv, that is making Oklahoma a hub for regional dining experiences.

At Owamni, my restaurant in Minneapolis, my team focuses on decolonizing our diet, removing ingredients like wheat flour, dairy, sugar, beef, pork, and chicken, all items introduced to the region not long ago. Through our cuisine, we are showcasing what’s possible, with dishes like slow-braised elk tacos with fresh tortillas from Potawatomi corn — made at our Indigenous Food Lab — finished with tangy maple-pickled onions, grilled sweet potatoes with maple and chiles; or slow-smoked bison short rib with bitter aronia berries, finished with pickled squash.

It is unfortunately still rare to find Indigenous food businesses like these. One barrier is trying to define Native American food in a country that has no idea what that means, especially breaking down the oversimplified category of “Native food” to reveal the immense diversity across foodways. Another barrier is financing; good luck finding any of the support required to start businesses on a reservation, without a rich uncle, outside investors, or even reliable access to a bank account. Racial inequalities are very much baked into the systems and institutions needed to launch a restaurant.

Dismantling these barriers would require a lot of work, but it could start in public spaces. State and city governments can purchase from Indigenous food producers, such as farmers, foragers, hunters, and fisheries, which would help strengthen and grow much-needed food economies. Indigenous offerings should be made available in schools and hospitals to help normalize these ingredients on menus. If we highlight foods and cultures so they are not only acknowledged but cherished, a future can develop where the richness of our collective heritage is a source of pride and inspiration for every American. We can learn to embrace our amazing diversity instead of fearing it.

Indigenous foodways are attainable models of sustainability, offering a proud connection to the land. They also provide a path to food sovereignty, enshrining the right for Native peoples to define themselves on their own terms. But even if those arguments aren’t acknowledged by those who have ignored Indigenous needs for so long, Native restaurants could begin to rewrite the reputation of “flyover country.” The heartland could become a more desirable tourist destination, not just for its natural beauty, but for its cultural and culinary heritage. With every plate of smoked venison, heirloom hominy, or stewed rabbit, we get a little closer.

You are on Native land, so let us celebrate the vibrant, varied tapestry that is the true heart of America.

Help us keep digging!

FERN is a nonprofit and relies on the generosity of our readers. Please consider making a donation to support our work.

Cancel monthly donations anytime.

Concerns grow about Christian nationalism in North Dakota

ND raw milk producers cautious as federal producers raise concerns

With advancements, EVs could make more sense for rural North Dakota

FBI sent several informants to Standing Rock protests, court documents show

Up to 10 informants managed by the FBI were embedded in anti-pipeline resistance camps near the Standing Rock Sioux Indian Reservation at the height of mass protests against the Dakota Access pipeline in 2016. The new details about federal law enforcement surveillance of an Indigenous environmental movement were released as part of a legal fight between North Dakota and the federal government over who should pay for policing the pipeline fight. Until now, the existence of only one other federal informant in the camps had been confirmed.

The FBI also regularly sent agents wearing civilian clothing into the camps, one former agent told Grist in an interview. Meanwhile, the Bureau of Indian Affairs, or BIA, operated undercover narcotics officers out of the reservation’s Prairie Knights Casino, where many pipeline opponents rented rooms, according to one of the depositions.

The operations were part of a wider surveillance strategy that included drones, social media monitoring, and radio eavesdropping by an array of state, local, and federal agencies, according to attorneys’ interviews with law enforcement. The FBI infiltration fits into a longer history in the region. In the 1970s, the FBI infiltrated the highest levels of the American Indian Movement, or AIM.

The Indigenous-led uprising against Energy Transfer Partners’ Dakota Access oil pipeline drew thousands of people seeking to protect water, the climate, and Indigenous sovereignty. For seven months, participants protested to stop construction of the pipeline and were met by militarized law enforcement, at times facing tear gas, rubber bullets, and water hoses in below-freezing weather.

After the pipeline was completed and demonstrators left, North Dakota sued the federal government for more than $38 million — the cost the state claims to have spent on police and other emergency responders, and for property and environmental damage. Central to North Dakota’s complaints are the existence of anti-pipeline camps on federal land managed by the Army Corps of Engineers. The state argues that by failing to enforce trespass laws on that land, the Army Corps allowed the camps to grow to up to 8,000 people and serve as a “safe haven” for those who participated in illegal activity during protests and caused property damage.

In an effort to prove that the federal government failed to provide sufficient support, attorneys deposed officials leading several law enforcement agencies during the protests. The depositions provide unusually detailed information about the way that federal security agencies intervene in climate and Indigenous movements.

Until the lawsuit, the existence of only one federal informant in the camps was known: Heath Harmon was working as an FBI informant when he entered into a romantic relationship with water protector Red Fawn Fallis. A judge eventually sentenced Fallis to nearly five years in prison after a gun went off when she was tackled by police during a protest. The gun belonged to Harmon.

Manape LaMere, a member of the Bdewakantowan Isanti and Ihanktowan bands, who is also Winnebago Ho-chunk and spent months in the camps, said he and others anticipated the presence of FBI agents, because of the agency’s history. Camp security kicked out several suspected infiltrators. “We were already cynical, because we’ve had our heart broke before by our own relatives,” he explained.

“The culture of paranoia and fear created around informants and infiltration is so deleterious to social movements, because these movements for Indigenous people are typically based on kinship networks and forms of relationality,” said Nick Estes, a historian and member of the Lower Brule Sioux Tribe who spent time at the Standing Rock resistance camps and has extensively researched the infiltration of the AIM movement by the FBI. Beyond his relationship with Fallis, Harmon had close familial ties with community leaders and had participated in important ceremonies. Infiltration, Estes said, “turns relatives against relatives.”

Less widely known than the FBI’s undercover operations are those of the BIA, which serves as the primary police force on Standing Rock and other reservations. During the NoDAPL movement, the BIA had “a couple” of narcotics officers operating undercover at the Prairie Knights Casino, according to the deposition of Darren Cruzan, a member of the Miami Tribe of Oklahoma who was the director of the BIA’s Office of Justice Services at the time.

It’s not unusual for the BIA to use undercover officers in its drug busts. However, the intelligence collected by the Standing Rock undercovers went beyond narcotics. “It was part of our effort to gather intel on, you know, what was happening within the boundaries of the reservation and if there were any plans to move camps or add camps or those sorts of things,” Cruzan said.

A spokesperson for Interior Secretary Deb Haaland, who oversees the BIA, also declined to comment.

According to the deposition of Jacob O’Connell, the FBI’s supervisor for the western half of North Dakota during the Standing Rock protests, the FBI was infiltrating the NoDAPL movement weeks before the protests gained international media attention and attracted thousands. By August 16, 2016, the FBI had tasked at least one “confidential human source” with gathering information. The FBI eventually had five to 10 informants in the protest camps — “probably closer to 10,” said Bob Perry, assistant special agent in charge of the FBI’s Minneapolis field office, which oversees operations in the Dakotas, in another deposition. The number of FBI informants at Standing Rock was first reported by the North Dakota Monitor.

According to Perry, FBI agents told recruits what to collect and what not to collect, saying, “We don’t want to know about constitutionally protected activity.” Perry added, “We would give them essentially a list: ‘Violence, potential violence, criminal activity.’ To some point it was health and safety as well, because, you know, we had an informant placed and in position where they could report on that.”

The deposition of U.S. Marshal Paul Ward said that the FBI also sent agents into the camps undercover. O’Connell denied the claim. “There were no undercover agents used at all, ever.” He confirmed, however, that he and other agents did visit the camps routinely. For the first couple months of the protests, O’Connell himself arrived at the camps soon after dawn most days, wearing outdoorsy clothing from REI or Dick’s Sporting Goods. “Being plainclothes, we could kind of slink around and, you know, do what we had to do,” he said. O’Connell would chat with whomever he ran into. Although he sometimes handed out his card, he didn’t always identify himself as FBI. “If people didn’t ask, I didn’t tell them,” he said.

He said two of the agents he worked with avoided confrontations with protesters, and Ward’s deposition indicates that the pair raised concerns with the U.S. marshal about the safety of entering the camps without local police knowing. Despite its efforts, the FBI uncovered no widespread criminal activity beyond personal drug use and “misdemeanor-type activity,” O’Connell said in his deposition.

The U.S. Marshals Service, as well as Ward, declined to comment, citing ongoing litigation. A spokesperson for the FBI said the press office does not comment on litigation.

Infiltration wasn’t the only activity carried out by federal law enforcement. Customs and Border Protection responded to the protests with its MQ-9 Reaper drone, a model best known for remote airstrikes in Iraq and Afghanistan, which was flying above the encampments by August 22, supplying video footage known as the “Bigpipe Feed.” The drone flew nearly 281 hours over six months, costing the agency $1.5 million. Customs and Border Protection declined a request for comment, citing the litigation.

The biggest beneficiary of federal law enforcement’s spending was Energy Transfer Partners. In fact, the company donated $15 million to North Dakota to help foot the bill for the state’s parallel efforts to quell the disruptions. During the protests, the company’s private security contractor, TigerSwan, coordinated with local law enforcement and passed along information collected by its own undercover and eavesdropping operations.

Energy Transfer Partners also sought to influence the FBI. It was the FBI, however, that initiated its relationship with the company. In his deposition, O’Connell said he showed up at Energy Transfer Partners’ office within a day or two of beginning to investigate the movement and was soon meeting and communicating with executive vice president Joey Mahmoud.

At one point, Mahmoud pointed the FBI toward Indigenous activist and actor Dallas Goldtooth, saying that “he’s the ring leader making this violent,” according to an email an attorney described.

Throughout the protests, federal law enforcement officials pushed to obtain more resources to police the anti-pipeline movement. Perry wanted drones that could zoom in on faces and license plates, and O’Connell thought the FBI should investigate crowd-sourced funding, which could have ties to North Korea, he claimed in his deposition. Both requests were denied.

O’Connell clarified that he was more concerned about China or Russia than North Korea, and it was not just state actors that worried him. “If somebody like George Soros or some of these other well-heeled activists are trying to disrupt things in my turf, I want to know what’s going on,” he explained, referring to the billionaire philanthropist, who conspiracists theorize controls progressive causes.

To the federal law enforcement officials working on the ground at Standing Rock, there was no reason they shouldn’t be able to use all the resources at the federal government’s disposal to confront this latest Indigenous uprising.

“That shit should have been crushed like immediately,” O’Connell said.

This story was originally published by Grist with the headline FBI sent several informants to Standing Rock protests, court documents show on Mar 15, 2024.