Sudden cut of ‘politicized’ FEMA grants leaves ND communities in the lurch

A sudden cancellation of Federal Emergency Management Agency grants supporting over $20 million worth of disaster mitigation infrastructure projects across the state has communities scrambling to figure out their next moves.

An April 4 press release from FEMA announcing the cuts characterized the Building Resilient Infrastructure and Communities (BRIC) program as “wasteful and ineffective” and “more concerned with political agendas than helping Americans affected by natural disasters.”

The statement said ending the program aligns with the Trump administration and Department of Homeland Security secretary Kristi Noem’s ideas on how to best support states and local communities in disaster response, planning and recovery.

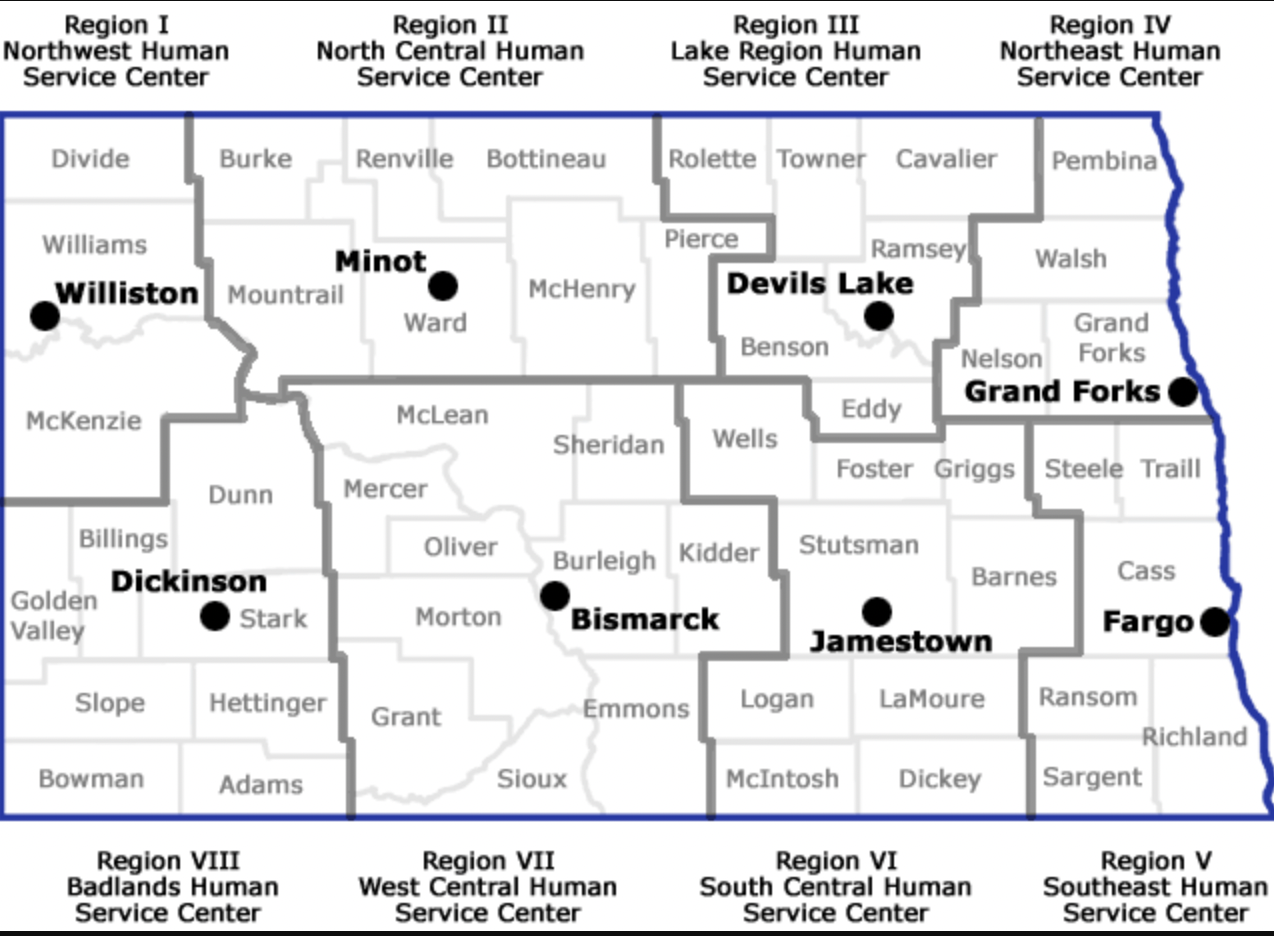

Washburn, Fessenden and Lincoln are three North Dakota communities that could be severely impacted. Planning on projects was years in the making. In some cases local funds were already spent for design, engineering, environmental reviews and legal work.

Keli Berglund, mayor of Lincoln just southeast of Bismarck, said cost estimates on the much-needed sewer wastewater regionalization project had doubled just in the past year from around $10 million to $20 million.

The FEMA grant would have helped cover $7.8 million in costs associated with the project, which has been in the planning phase since 2019, she said.

“Now what do we do?” Berglund asked. “We are, if not at capacity, we are near capacity,” to handle wastewater.

“One big flood and who knows?” she added.

Engineering costs already total over $200,000, she said. Adding in other legal fees and easement contracts brings the total much higher for what’s already been spent.

“We’re literally looking at hundreds of thousands of dollars,” Berglund said.

“I’m hopeful there’ll be a resolution either by FEMA releasing the funds or legislators stepping in,” she said.

Chelsey Brandt, city auditor in Washburn, said the $7.1 million in FEMA grant money was set to go toward a new water intake system that was “years in the making.”

Washburn hasn’t spent much on the project so far, she said, since most of the planning was being conducted by Garrison Diversion Conservancy District.

“I guess that just puts us back to the drawing board of trying to see if we are pursuing a new intake if that’s the way Washburn wants to go,” Brandt said.

In Fessenden, with just under 500 residents, a $1.9 million BRIC grant was meant to upgrade a wastewater lagoon that’s over 100 years old, making it the oldest in the U.S. along with a lagoon in San Antonio, Texas.

“Anything that’s 102 years old obviously needs some work,” said Tammy Roehrich, Wells County Emergency Manager.

The project would have involved dredging, stabilizing and wrapping the banks. Bids for work on the project were set to go out on May 1, Roehrich said. Fessenden had already spent around $165,000 in upfront planning costs.

Another BRIC grant in Wells County was meant to cover $366,000 in costs for a new generator at SMP Health-St. Aloisius Medical Center, but that’s been canceled as well.

Similarly, a $132,000 grant for a new generator for Carrington Medical Center in Foster County was also canceled.

Most of the remaining BRIC grants that were axed were for flood and flood risk reduction studies.

Another 19 projects that FEMA has already obligated to fund are now under review, so those are currently in limbo. Included in those are a grant for $262,000 for a downtown core area flood study and $278,000 for a sewer system lift study, both for West Fargo.

A study from the National Institute of Building Sciences in 2018 found that for every $1 spent on hazard mitigation resulted in an estimated $6 saved on recovery costs, and North Dakota surpasses the national average at around $6.54 saved per $1 spent.

The state estimates that mitigation investments in the state have already saved over $1.9 billion in recovery costs.

According to an April 8 statement issued by the Department of Emergency Services, Gov. Kelly Armstrong has directed state agencies to work with local communities to explore options and find other solutions for key infrastructure projects.

Darin Hanson, director of Homeland Security, a division within the Department of Emergency Services, said his department is working on trying to find alternative funding sources including state programs.

“They’re important projects, they really are,” Hanson said.

Asked if any of these projects fit the description of being wasteful, ineffective or politicized, Hanson didn’t agree.

“I think in North Dakota, we really try to keep the politics out of these public safety decisions. You know, we see that in the fires from last year. It’s neighbors helping neighbors, so I don’t think it’s as big of an issue in North Dakota,” Hanson said.

Hanson said North Dakota has been a national leader in mitigation projects like the ones impacted by a loss of federal funding.

“We want to keep trying to find ways to get these projects done because they’re important,” Hanson said. “If you look at where we’ve done projects in other parts of the state, it’s made a big difference.”

The North Dakota News Cooperative is a nonprofit news organization providing reliable and independent reporting on issues and events that impact the lives of North Dakotans. The organization increases the public’s access to quality journalism and advances news literacy across the state. For more information about NDNC or to make a charitable contribution, please visit newscoopnd.org. Send comments, suggestions or tips to michael@newscoopnd.org. Follow us on Twitter: https://twitter.com/NDNewsCoop.