Electrifying Democracy in Rural America

This is the sixth installment of Barn Raiser’s 2024 election coverage series “Charting a Path of Rural Progress,” which features interviews with rural policy experts and organizers who came together in Omaha, Nebraska, in 2023 to forge a rural policy platform on which candidates can run—and to which voters can hold their elected leaders accountable. The platform that grew out of that Omaha meeting, A Roadmap for Rural Progress: 2023 Rural Policy Action Report, released last October, details 27 legislative priorities for rural and small town America, based on legislation that has already been introduced in Congress.

Erik Hatlestad, 33, works on rural energy issues with the Minnesota nonprofit CURE (Clean Up the River Environment) as their Energy Democracy Program Director. Founded in 1992, CURE describes itself as a rural-focused environmental group “rooted in the movement for rural social justice.” The group’s 12 employees are scattered in small towns across the state.

Hatlestad is currently on a six-month stint with the U.S. Department of Agriculture’s Rural Utilities Service (RUS) as a Clean Energy Benefits Advisor, where he leads the Empowering Rural America (New ERA) program, a historic investment in rural electrification that is based, in part, on Hatlestad’s 2019 report, “Rural Electrification 2.0: The Transition to a Clean Energy Economy,” which outlines the role of rural electric cooperatives in the transition to clean energy in rural America.

Hatlestad, grew up with two brothers on a small family farm, growing corn and soybeans, about 10 miles from New London, Minnesota (population 1,252), in Kandiyohi County, where he now lives.

How did you get into rural political activism?

I grew up shortly after the farm crisis of the 1970s and 80s, which shaped the hollowing out of rural communities that we’re still seeing today. We saw the end of several of our local farm cooperatives in New London and western Minnesota, because all of the members had been driven out of business.

Fighting for rural communities to regain control over their own future—a future that has been taken from them by exploitative markets and large agribusiness—is personally important to me. And I like to continue that historic legacy of the agrarian movement from yesteryear.

I’m very, very committed to rural democracy and building democratic solutions for small towns. I’m involved with a number of community projects in New London I’ve helped run the community theater and cocktail bar, and just helped opened a food cooperative, which will be the first grocery store in our town for the last 15 years. I serve on a lot of different boards and am very involved with Farmers Union and was until recently on the board of the city council.

How does the Rural Policy Action Report address the challenges rural America faces?

The biggest problem is that rural America has faced underinvestment and disinvestment for so long.

In previous decades, we had strong rural social movements that fought for these big investments, like the original Rural Electrification Act and the New Deal, and all of these incredible programs that helped make rural America what it is—or what people like to think they remember it as. Those social movements and organizations were crushed during the 1980s farm crisis and as a part of deindustrialization, such as with NAFTA and the offshoring of manufacturing jobs, and the right-wing attack on organized labor. As a result, rural social movements haven’t had the political strength to put forward the alternative solutions that were historically offered to rural people to win new investments in their communities.

What the Rural Democracy Initiative—the group that sponsored the Omaha summit out of which came the Rural Policy Action Report—has done is bring momentum back to rural social movements by offering an alternative to the disinvestment and the race to the bottom and what has been the essential hollowing out of rural communities.

The Rural Policy Action Summit was held in Omaha, Nebraska, which is where the Populist Party held its first convention back in 1892. Is that ancient history?

For all of us who are involved in creating a progressive future for rural America, there isn’t a day that goes by where we don’t think about these historic social movements and what they were able to accomplish in the same communities we live in today.

For those of us in rural Minnesota and the Dakotas, we love to think about the Nonpartisan League and the Farmer-Labor Party and how they transformed the states by gaining political power—creating state grain elevators, and in North Dakota, creating the country’s only state-owned bank. And the incredible progress that was made by farmer labor governors in Minnesota.

There’s a common thread among all of them, starting back with National Grange of the Order of Patrons of Husbandry beginning in 1867 and flowing into movements that would become the Populist Party [People’s Party] and the Progressive Party. We look to them as inspiration for what we’re doing today.

The co-operative movement was really born in Minnesota. The congressman (Andrew Volstead) who co-wrote the Capper Volstead Act, which legalized co-ops in 1922, was from Granite Falls, Minnesota. Some people call it the Magna Carta of cooperatives in the U.S. The first electric co-op in the country was the Stony Run Light and Power Company, which was just south of Granite Falls, near CURE’s offices. It’s a history that is barely outside of living memory, but it’s certainly something that we think about on a daily basis.

How would a transition to clean energy affect rural communities and the rural electrical cooperatives of which 42 million Americans are members of?

A few years ago, I was one of the authors of a white paper called Rural Electrification 2.0, where we took a look at the historic and systemic barriers holding up the clean energy transition in electric cooperatives and we made some of the policy recommendations in that report.

Since then, we have been working to build support for an investment in rural electrification to clear the way for the clean energy transition, and part of that work has been through the Rural Policy Summit in Omaha and the resulting Rural Policy Action Report.

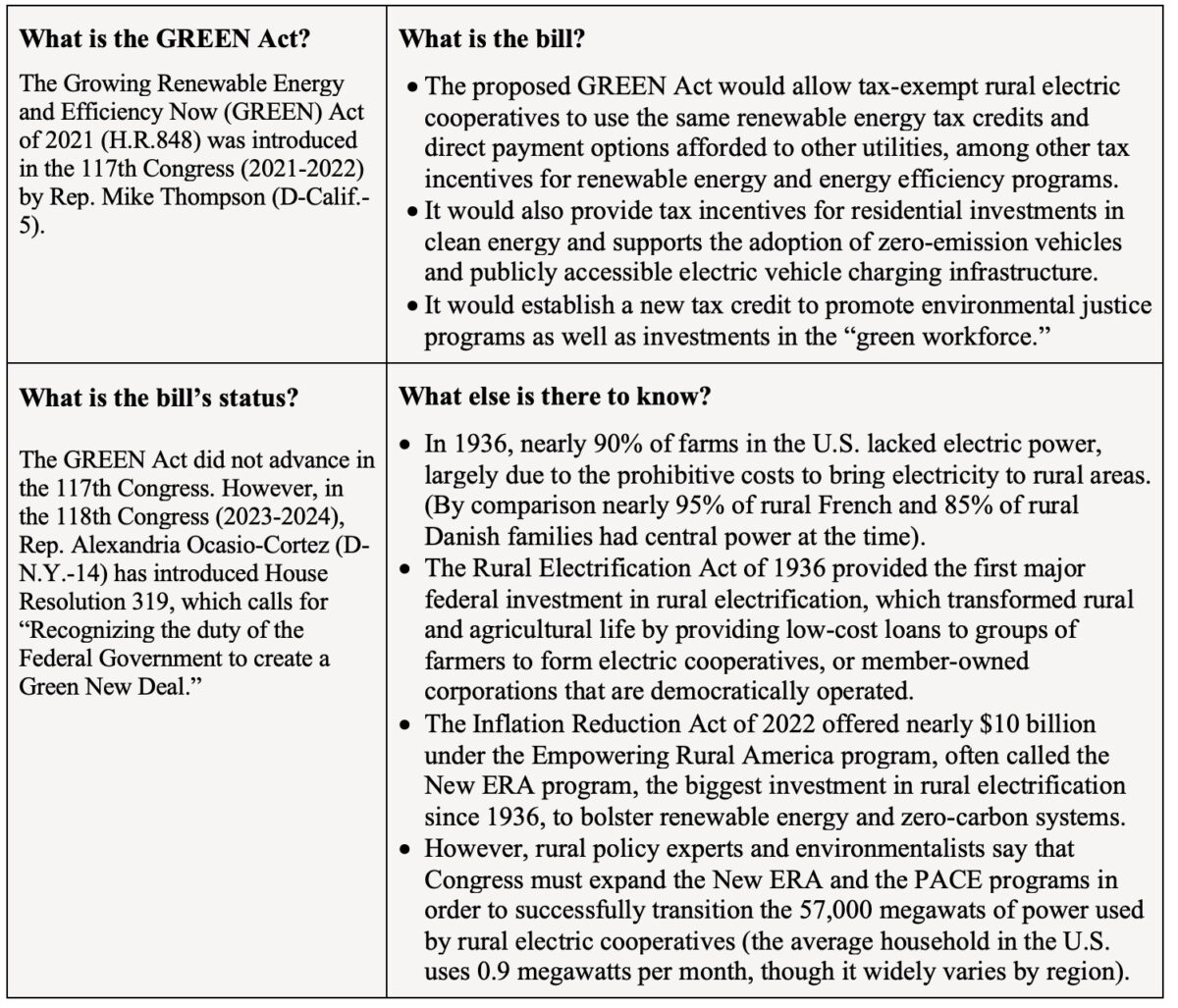

Many organizations, including National Farmers Union, Sierra Club and the National Rural Electric Cooperative Association themselves have all come around to the concepts that we put forth in Rural Electrification 2.0. Reinvestment in rural electric co-ops was one of the key programs that the Biden administration listed in their rural investments portfolio when they took office. Our programs made it through every single edition of Build Back Better and were eventually passed in the Inflation Reduction Act and the implementation process has begun over the past year. Those programs are now known as Empowering Rural America, or New ERA, and the Powering Affordable Clean Energy Program, or PACE.

How accessible is the program? I heard that the application process can be a daunting for individual rural electric cooperatives.

There is an urgent need to get the program money out the door before potential cuts could be made to the program by Congress. The U.S. hasn’t done a major investment in rural electrification like this since the 1930s. So co-op staff and board members and the communities themselves aren’t accustomed to thinking as big as they’ve been given the opportunity to now. It has been problematic for rural utilities and rural communities to pursue federal grants at the same level as communities that are better resourced.

Having spent some time in small town government on city council myself, I understand how staff are already overworked and underpaid. It’s tough to ask people in similar positions, whether it’s an electric co-op or a small town team, to take on a robust federal grant making process.

So there are some challenges. But the response that co-ops gave to these programs is overwhelming. The programs have received over 140 applications from the 40 states, and there are about 900 rural electric co-ops, and they are only active in 46 states. But a number of these applications represent coalitions of co-ops or generation transmission co-ops applying on behalf of their distribution members. So we can credibly say that half of all co-ops in the country showed interest in this program.

You dated the start of the rural decline back to the farm crisis of the 1970s and 80s. Why do you date it back to then? Some people say it begins back with Earl Butz in the early 1970s when he was secretary of agriculture under Nixon and told farmers to “get big or get out.”

I would generally agree that it started with Butz and agribusiness companies and the fertilizer industry essentially concluding that the best way to protect their own profitability was to make sure that farms got bigger and bigger and bigger. It’s a historic arc similar to the attack on organized labor that happened over the last half of the 20th century, which you could summarize that as being a coordinated attack on the New Deal coalition by business interests and their political allies.

It started with Butz and the encouragement of bigger and bigger farms and culminated in the 1970s and 80s with the farm crisis, and dealt one of the finishing blows to the agricultural system of family farming, which had been a solid political block organized around the co-operative principles of the cooperative movement. You see similar kind of tropes play out with the deindustrialization in the Rust Belt, the consolidation of bigger businesses and the promotion of free trade.

Did you did your county vote for Donald Trump?

Oh, yes.

How do you think about bridging political divides within your county and rural America in general?

You don’t bridge some of those divides, you provide an alternative. For too long, people who would not call themselves Republicans have not had the ability to articulate any kind of alternative. Democrats have spent too long trying to say, “We’re just the same, we’re just not so scary.” That is part of the problem we face here: no one has provided an alternative.

People in rural communities feel—and I would certainly count a lot of Trump supporters in this as well—totally ignored. If I’m accustomed to, as a rural community, being ignored and being disinvested from, and I don’t have the kind of political institutions that used to exist, well, I’m just going to do the thing that makes the people who I know are making my life worse as mad as possible: I’m going to vote for the most insane person. I’m not going to be heard anyway, so why should I seriously participate in the process?

We need to provide an alternative that we can articulate that resonates with people. Like the Ohio referendum on abortion on November 7, for instance. Strong progress was made in a lot of rural communities in Ohio, thanks in part to organizers who were putting an alternative out there and actively talking to people.

It’s about helping rural people feel comfortable expressing the views that they have, because so many people in these places feel isolated. There’s certainly a social aspect to that, too, but it’s also a product of decades of disinvestment and disenfranchisement. Attempts to rebuild those historic political institutions around progressive policy ideals are predicated on presenting such alternatives.

Why do you think the Democratic Party has for so many years failed in that?

A lot of people struggle with that question, and I do as well. There hasn’t been much political leadership in the party coming from rural parts of the country. In part, the party has been disconnected from these communities because the people who would participate in these movements have left rural areas. And part of it is the acquiescence of some Democratic Party leaders to mirror their opposition and buy into the ideas of so-called free trade, which has accelerated the decline and disinvestment in rural communities.

A summary answer would be: the Democratic Party’s loss of soul, the loss of its identity as an institution.

The post Electrifying Democracy in Rural America appeared first on Barn Raiser.