Aroostook power corridor faces opposition from rural landowners

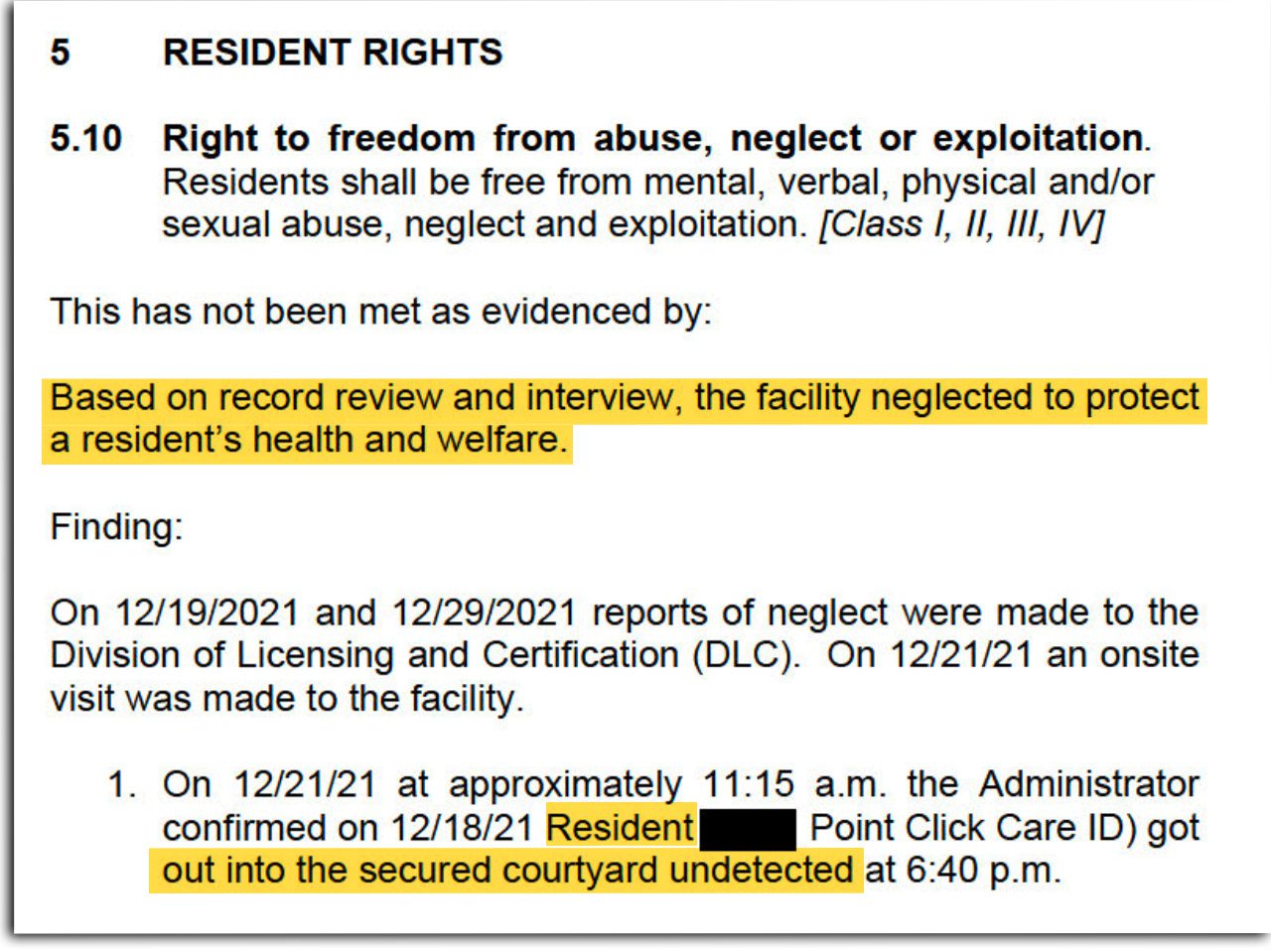

ALBION — Over 50 years, Eric and Rebecca Rolfson have created a rural oasis in this central Maine farming community. On 123 acres, they have hand-built a log cabin and renovated a 200- year-old family farmhouse.

They have created a maple syrup business, cultivated hayfields that serve local dairy farmers and cut a community trail system through their woods. This is where they plan to grow old, on land where Eric Rolfson’s parents are buried.

So they were shocked last July when they received a letter from LS Power, a New York City-based power and transmission system developer.

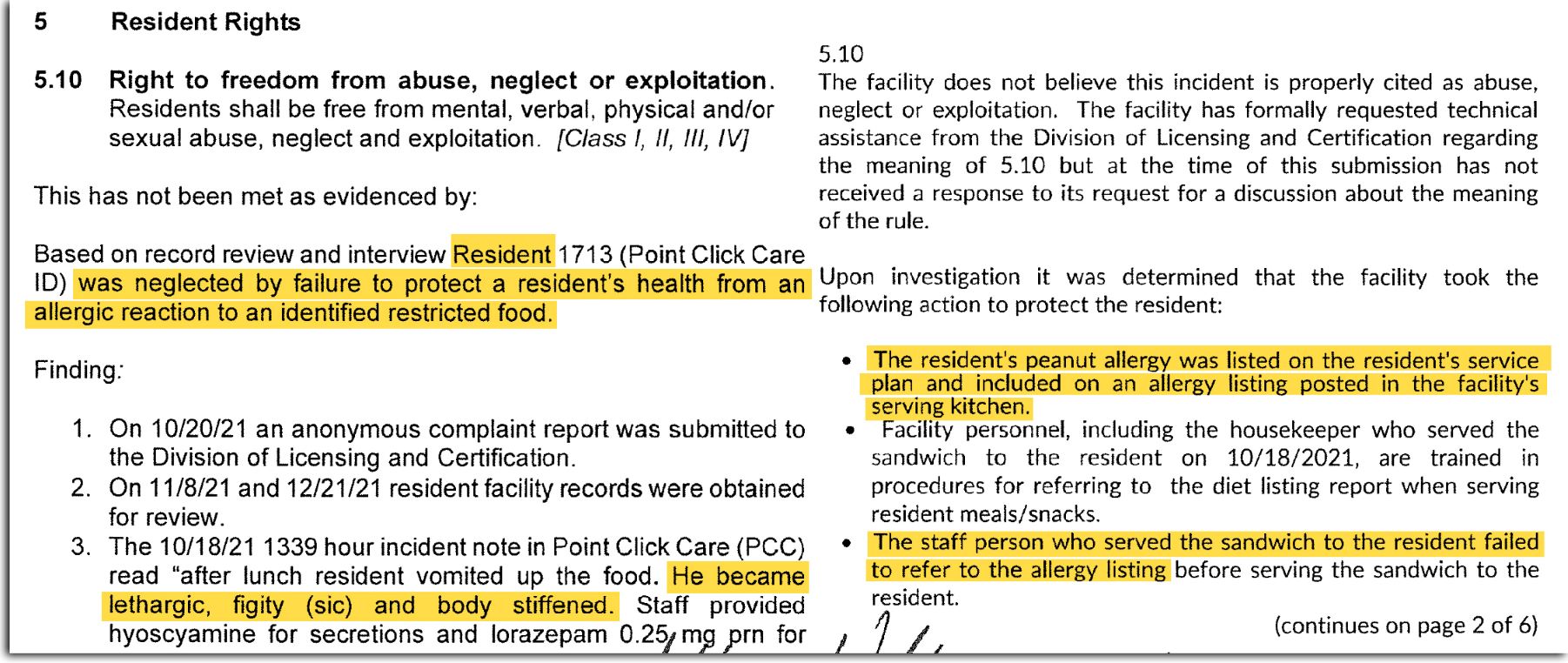

The Rolfsons learned they were among 3,500 or so landowners with property on the potential route of the Aroostook Renewable Gateway, a roughly 140-mile overhead transmission line that would connect the largest wind farm east of the Mississippi River with New England’s electric grid.

A map shows a potential 150-foot wide corridor slicing north-south through the Rolfson’s property.

Standing in the farmhouse’s yard in mid-November, looking up at the wooded ridge that could someday trace the path of transmission lines strung from 110-foot towers, Eric Rolfson expressed his frustration and fear after a lifetime of pouring his heart into the land.

“We love it here,” he said. “We can’t imagine looking up at those towers.”

When it was approved last June by lawmakers and signed by Gov. Janet Mills, the bipartisan legislation enabling the Aroostook Renewable Gateway was hailed as an achievement that would finally unlock northern Maine’s green energy potential while lowering electric rates.

But already the Aroostook line is beginning to feel reminiscent of another controversial corridor — the troubled New England Clean Energy Connect project, the six-year effort by Central Maine Power’s parent company to build an overhead transmission line from Quebec to Lewiston.

After years of court battles, a citizens referendum was overturned in April and work was allowed to resume. Crews are being reassembled to finish the now-estimated $1.5 billion project, the company said, with plans to energize the line in 2025.

Meanwhile the Rolfsons, and neighbors in Albion, Palermo, Freedom, Thorndike and Unity, are organizing in opposition to the Aroostook line.

They have held protest rallies. They set up a Facebook page with 1,000 members and created a citizen group, Preserve Rural Maine. They’ve hired a Portland attorney with experience fighting transmission lines, including NECEC.

Nearly a dozen towns have enacted temporary moratoriums.

This wasn’t supposed to happen.

The 2021 citizens’ initiative aimed at killing NECEC also contained unprecedented language that requires the legislature to approve any new “high-impact electric transmission lines.”

The idea was to provide a check on developers seeking to push projects through communities that opposed them. The Aroostook line was the first test of the new law and, based on the fight brewing here, it’s not working as planned.

Two problems are becoming obvious. First, rank-and-file lawmakers were asked by key legislative leaders to endorse the project before even knowing where the transmission corridor would run. Second, language in an initial 2021 transmission line bill encouraged new lines to be located in existing rights-of-way or corridors “whenever feasible.” But feasible is a broad term, leaving it to developers to assess what’s technically and financially doable.

The prospect of new transmission corridors going through resistive communities has led some lawmakers to take a step back.

Eleven relevant bills were proposed for the upcoming legislative session, ranging from study alternatives to preventing eminent domain takeovers to rescinding approval altogether. None got the initial go-ahead this month from the Legislative Council, the 10-member leadership body that controls the flow of legislation, although one was granted on appeal. The council includes two Aroostook County lawmakers who are key champions of the project: Senate President Troy Jackson, a Democrat, and Senate Minority Leader Trey Stewart, a Republican.

There’s wide agreement that Maine and the region will need more transmission lines to carry clean energy and phase out the fossil fuel generation linked to climate change. But the highly organized opposition against the Aroostook venture is raising a critical question about how Maine is pursuing its interconnection goals.

What lessons have politicians and policy makers learned from the NECEC debacle, or from Northern Pass in New Hampshire, the failed attempt to construct a 192-mile overhead line from Quebec that was killed in 2018 after stiff community opposition?

Northern Pass, NECEC and Aroostook Renewable Gateway have something in common. They were designed to carry high-voltage power over lines strung on tall towers running through wide swaths.

By contrast, a similar-size project now being built from Quebec to New York City, the Champlain Hudson Power Express, plans to run cables underground and underwater in narrow corridors. Another cross-border proposal, Twin States Clean Energy Link, would put some of the line under state roadways.

The Aroostook Gateway is the product of decades-long ambitions to connect Maine’s northernmost county with New England’s electric grid, and boost the local economy by building wind, solar and biomass power plants.

It remains in its early stages, planned to come on line in 2029. LS Power has yet to seek key permits from utility and environmental regulators.

As the process unfurls, two additional questions loom: Will Maine push ahead with an unpopular overhead transmission design that has snarled two similar high-profile projects? With an eye on lessons from Northern Pass and NECEC, is it still possible to bury cables underground?

For its part, LS Power stresses that no routes have been finalized.

The company met in July with residents along proposed route options to hear their concerns. It plans a second round of meetings in early 2024 and expects to adjust the route based on feedback.

The route is subject to change until all permits are in hand, the company said, no sooner than 2026.

The company even explored placing towers along sections of Interstate 95, but that idea was rejected by the Maine Department of Transportation.

One thing not likely to change, according to Doug Mulvey, the company’s vice president for project development, is the alternating current, overhead wires design. LS Power is familiar with underground projects, working on one in San Jose, Calif., Mulvey said.

But burying a high-voltage line that carries the required direct current from Aroostook County to central Maine would cost roughly five times more than the overhead option, he said. That would be a non-starter because a top reason the $2.9 billion project won a competitive bid process at the Public Utilities Commission is it promised to save electric customers money.

“Everyone in the state, everyone we talked to, is extremely concerned about rates,” Mulvey said.

Adding to the complexity, LS Power and the PUC are bogged down in negotiations over details of the power purchase and transmission service agreements. Mulvey told the Portland Press Herald that the impasse was putting the project at risk.

Renewable energy versus ratepayers

The Aroostook Renewable Gateway checks a lot of boxes on the wish list for Maine’s clean energy aspirations.

The line would connect to a 170-turbine wind farm in southern Aroostook County called King Pine, to be built by Boston-based Longroad Energy. The $2 billion project would have a capacity of 1,000 megawatts, producing enough electricity to power 450,000 homes. Other generators, such as solar or biomass, might someday also be able to use the line.

In approving King Pine and the power line last January, the PUC estimated that most Maine residential electricity customers would pay an extra $1 a month — or $1 billion in total — for a 60% share of the project. The rest would be paid by Massachusetts customers as part of that state’s clean energy acquisitions. The actual megawatt-hour cost of electricity hasn’t been made public.

When it was approved by the PUC, the project was hailed by Mills’ energy office as a way to combat the impact of volatile natural gas costs on electricity supply, while creating economic opportunities in northern Maine. Jackson said it would unlock affordable, homegrown renewable energy and create good jobs.

“With today’s vote,” Jackson said at the time, “we are the closest the state has ever been to making the northern Maine transmission line a reality, and unleashing the untapped economic potential and power of Aroostook County.”

All this seemed far away in Albion, roughly 130 miles south of the planned wind project. This is dairy farm country in a state where the industry has been shrinking for decades. But here, 10 dairy farms hang on, evident by the hayfields and pastureland spread across rolling hills.

Driving the country roads, what sticks out most isn’t the cows. It’s the signs. Election season is over but what looks like roadside campaign signs are everywhere. Black-and-white signs read: “Keep LS Power off our land.” Yellow signs with an outline of a transmission tower say, “Stop Gateway Grid,” with the weblink, PreserveRuralMaine.org.

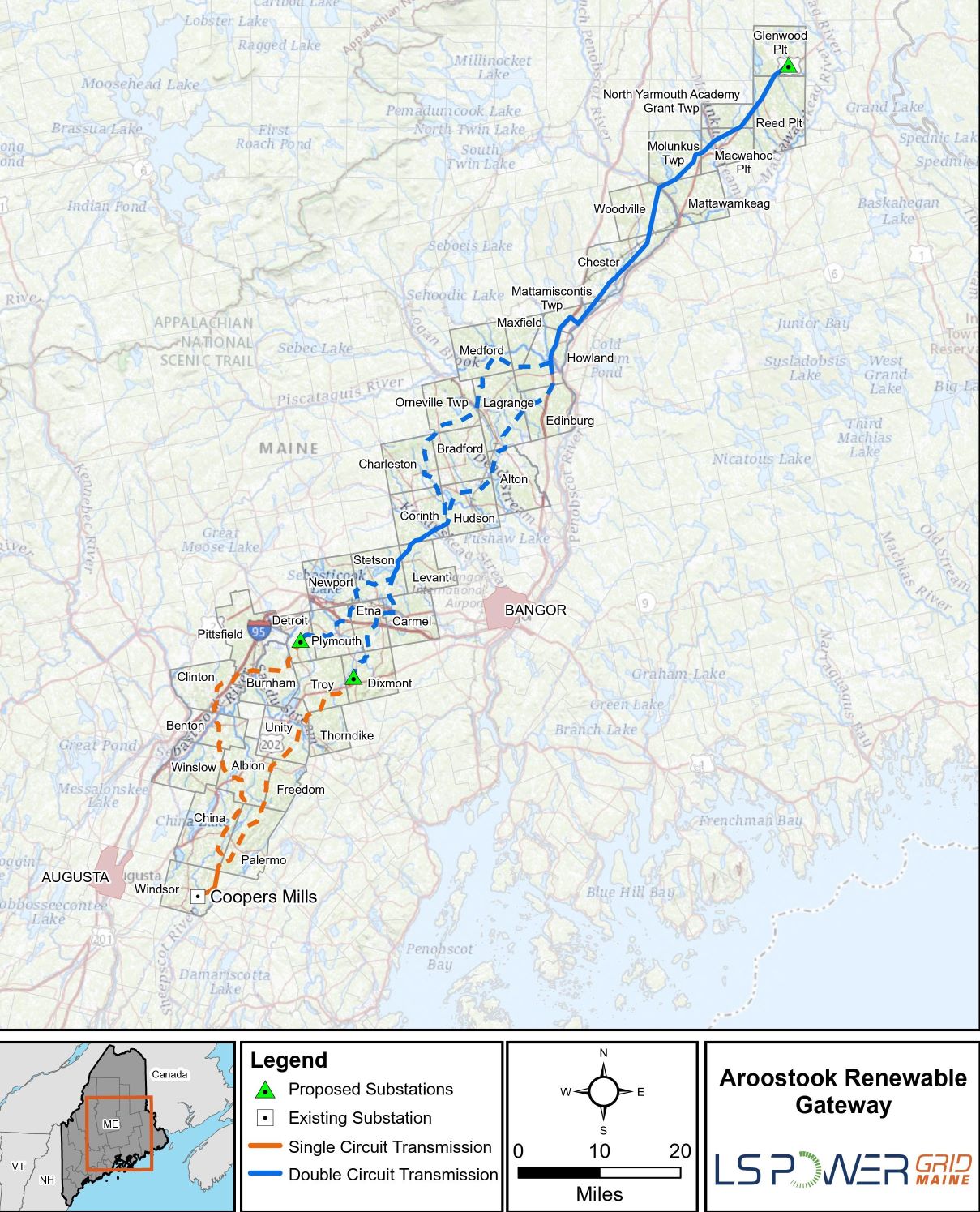

The signs are on the Noyes Family Farm, a third-generation dairy operation with 100 cows that grows corn and hay on 370 acres. Chuck Noyes and his daughter, Holly, were part of a protest at the Albion town office in late July. It was organized to call attention to concerns ranging from loss of farmland to electromagnetic radiation from overhead wires.

In mid-November, Holly Noyes came to the Rolfson farmhouse, with several residents who formed action committees in their communities, to talk about next steps. Over pancakes and the farm’s maple syrup, they discussed a path forward.

“What are our next steps if the legislature isn’t going to listen?” asked Josh Kercsmar of Unity, vice president of the Preserve Rural Maine group. “Where can we turn?”

‘No real input’

This is not what lawmakers had in mind in 2021 when they considered LD 1710. The bill created the Northern Maine Renewable Energy Development Program and directed the PUC to seek proposals for a transmission line that would ship power from green-energy generators in Aroostook County into the New England grid. Jackson, who represents a district in far northern Maine, was the lead sponsor.

But some interest groups that testified on the bill, such as the Maine Farmland Trust, urged lawmakers to remove the “wherever feasible” clause, to “ensure that there is a strong preference for proposals that are collocated with existing utility corridors and roads, and as such, avoid further impacts to important natural and working lands.” No changes were made.

And after the passage in June of LD 924, a follow-up, legislative resolve sponsored by Jackson, Stewart and others to signal specific approval for the Aroostook Gateway, some lawmakers felt the process was being rushed.

“My big concern,” said Rep. Steven Foster, R-Dexter, “is that we’re approving this line, it’s going through 41 communities, but there was no real input during the legislative process before the approval was made.”

Foster, who serves on the legislative committee that handles energy matters, represents towns through which the line could pass.

He proposed a bill for the upcoming session to reconsider the project’s PUC approval. It was rejected by leadership in early November, along with all but one of the proposed remedial measures — a bid from Sen. Chip Curry, D-Waldo, to prevent eminent domain from being used to build the line.

“I think (Senate) President Jackson and others are determined to get this project done,” Foster said. “And I’ll leave it at that.”

Jackson’s perspective, however, is that some lawmakers who oppose wind farms were “piling on” to create obstacles.

After meeting with the Albion-area organizers, Jackson said he’s sympathetic plight and wants LS Power to do its best to mitigate impacts. But he doesn’t see how the lines can be buried, based on the PUC’s bidding criteria.

“That’s not what the PUC asked for in its request for proposals,” Jackson told The Maine Monitor. “They would have to re-bid the whole thing. You’re going to have different costs and ratepayers are going to be impacted.”

But by selecting a project with overhead transmission lines, Maine is ignoring a lesson from both Northern Pass and NECEC, according to Beth Boepple, a Portland attorney who represented opponents in both cases. It’s technically feasible to run high-voltage cables underground along existing corridors or roadways, she said, and that’s what Maine should require.

“It’s one of the lessons we should have learned,” she said. “We don’t need to reinvent the wheel.”

One difference, Boepple said, is opponents have organized early. There’s still time to press the PUC and permitting agencies such as the Department of Environmental Protection to require underground cables. That could avoid long and costly legal battles, she said.

“We’re a long way from going to court,” she said. “There’s a lot that can be done through the permitting process.”

But even at this early stage, the process is fraught with competing tensions, according to Bill Harwood, Maine’s public advocate.

The developer requested and won some assurances before investing millions of dollars. But the legislature had to sign off on a major project without key information.

Customers statewide want lower-cost electricity. Local residents, though, don’t want giant towers and overhead wires on their land.

“Going forward,” Harwood said, “we need to think carefully about whether there’s a better way.”

The story Aroostook power corridor faces opposition from landowners appeared first on The Maine Monitor.