As Goes the Black Belt, So Goes Georgia

This is the second in a series of interviews, in which we will ask rural candidates, elected office holders, political consultants and organizers what lessons are to be learned from the 2024 General Election.

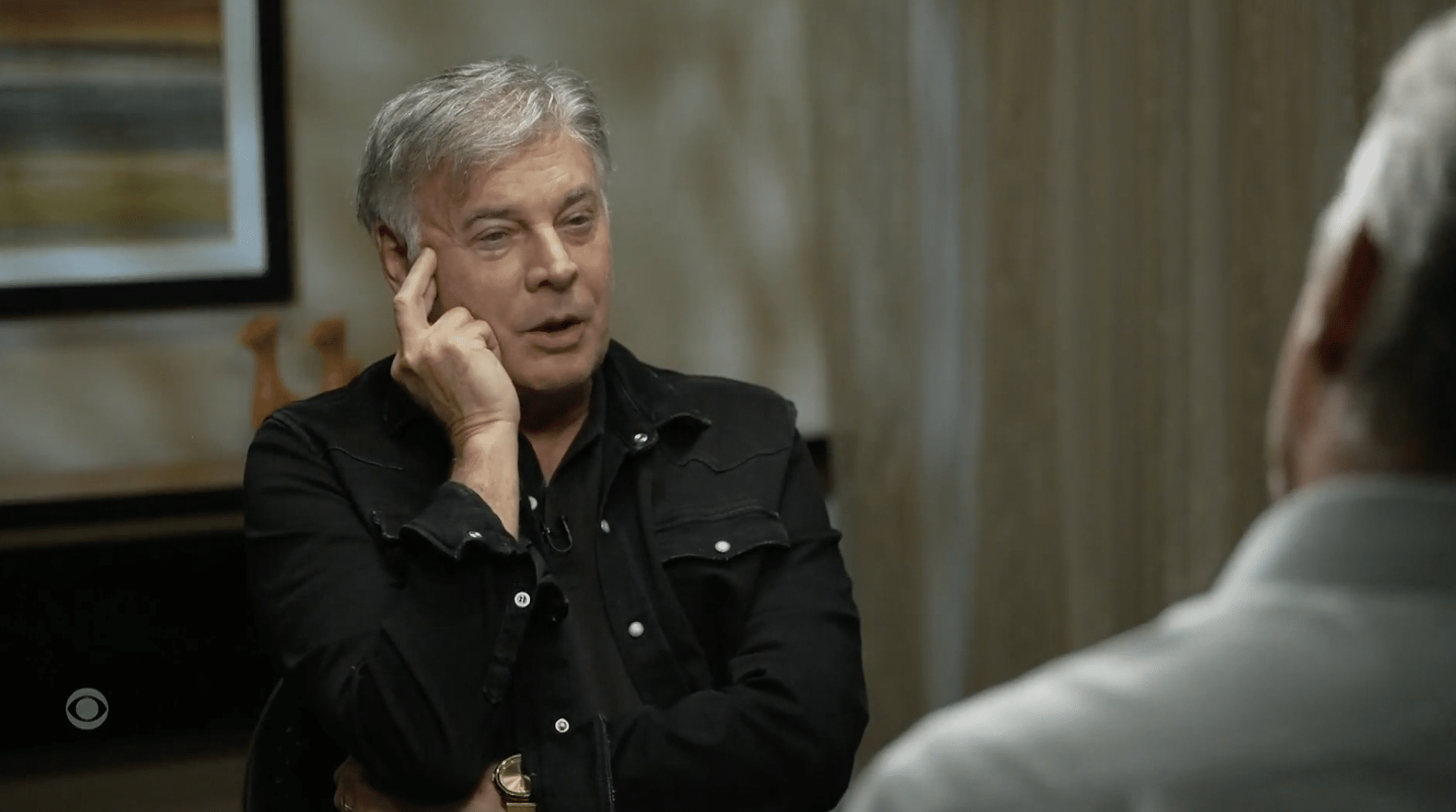

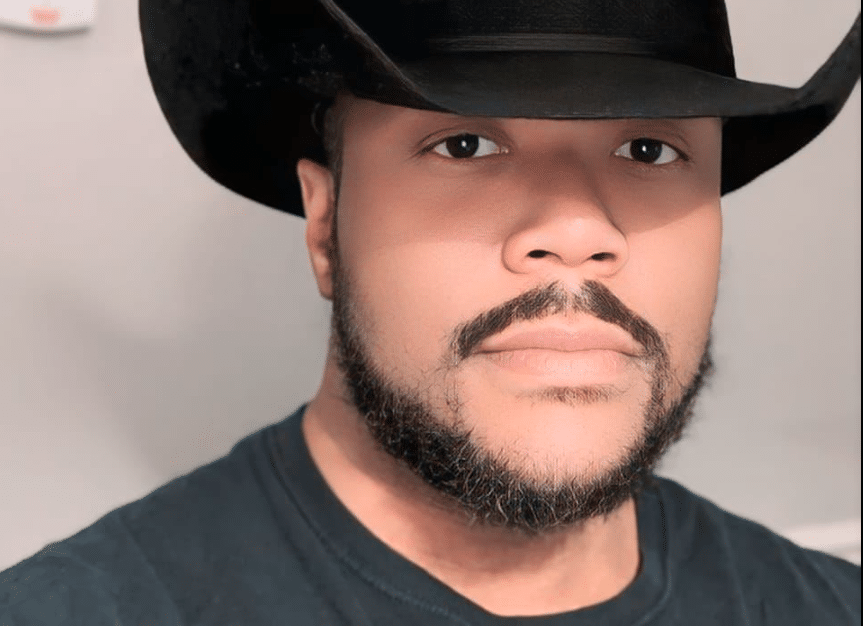

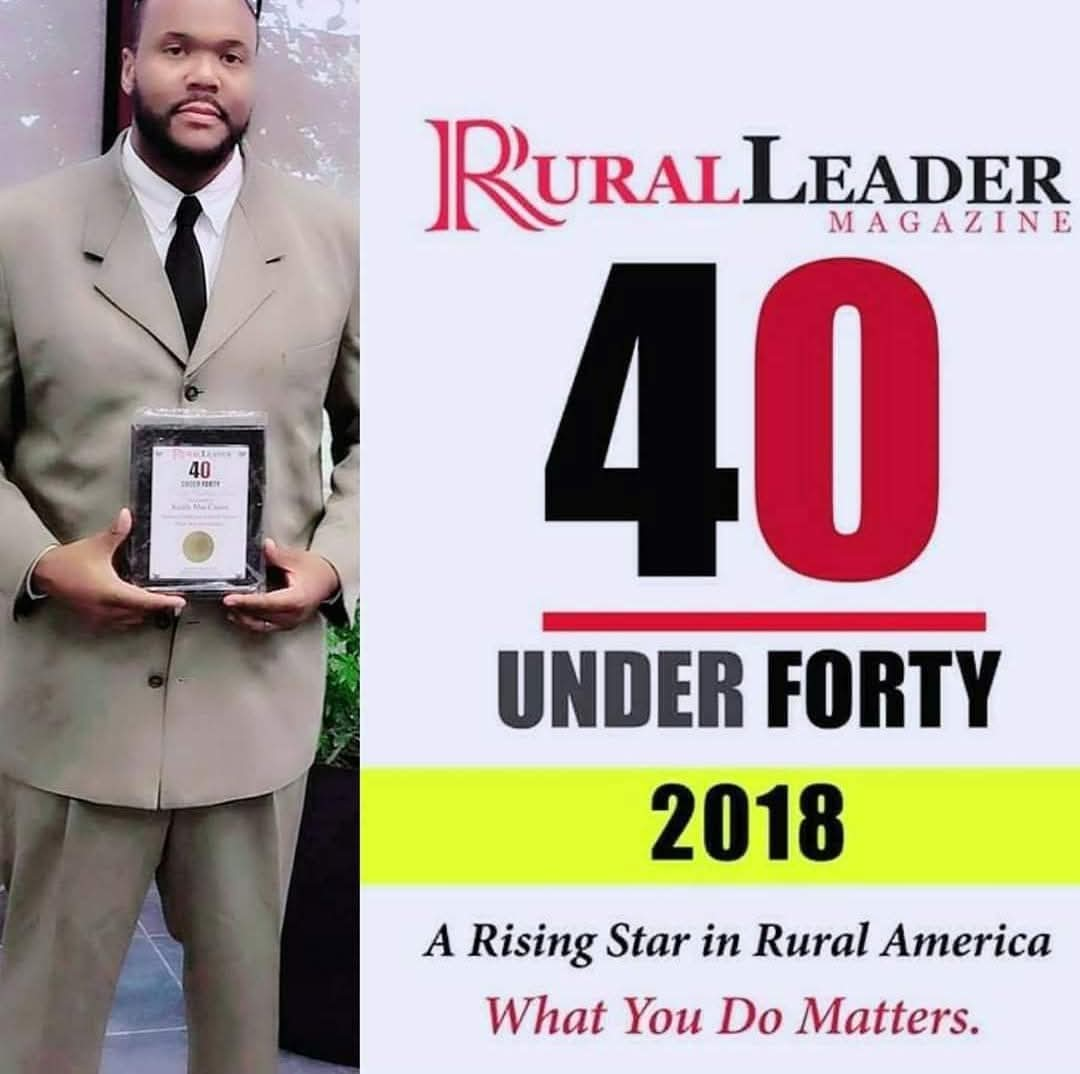

Keith McCants, 42, is the chair of the Democratic Party in Bryan County, Georgia. Located southwest of Savanah, this half-rural and half-suburban county is among the fastest growing in the state. On November 5, 68% of voters in Bryan County cast ballots for Donald Trump.

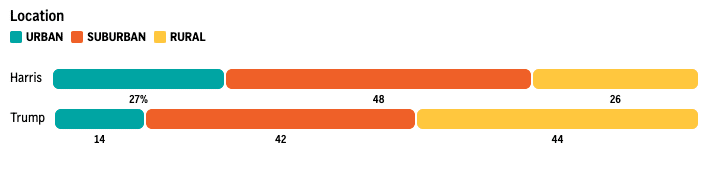

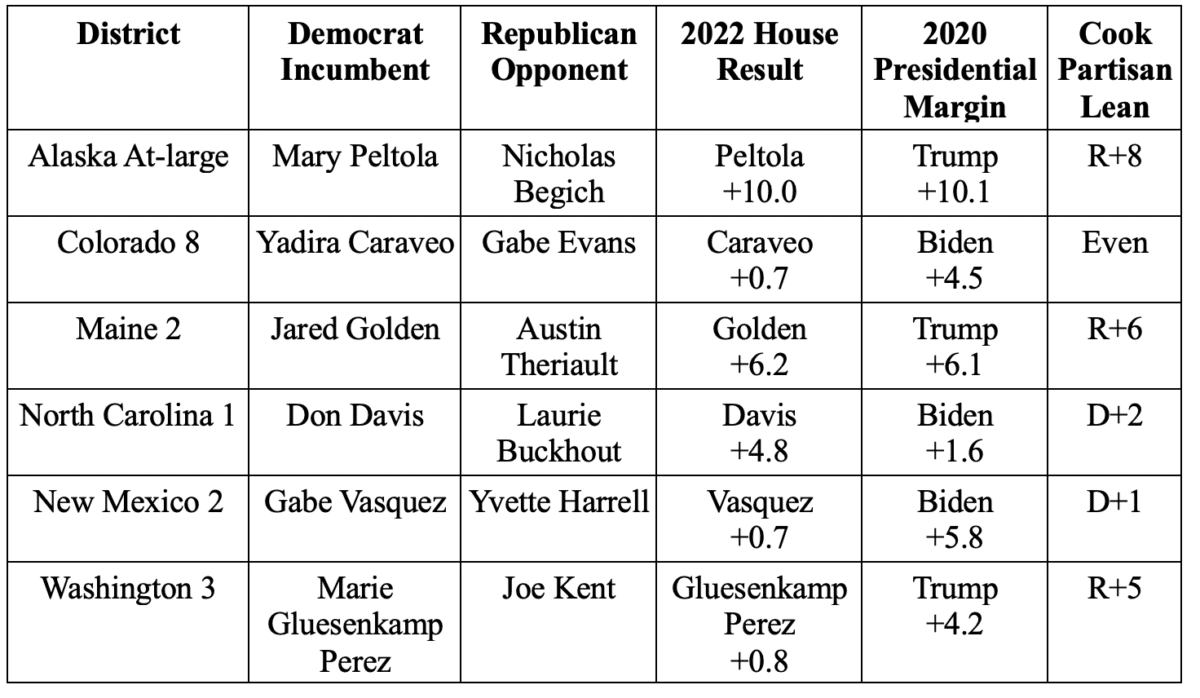

McCants describes himself as a “conservative Democrat” and identifies as a Blue Dog. The Blue Dog Coalition is a largely rural caucus of moderate Democrats in the House of Representatives. It is led by Reps. Marie Gluesenkamp Perez (Wash.-3), Jared Golden (Maine 2) and Mary Peltola (Alaska-at large), all three of whom represent House districts that Trump won. At its peak in 2009, the caucus boasted 54 members. It now has 11. Politico reports that the Blue Dog Caucus was “decimated in the 2010 election and has since drifted ideologically from pro-corporation centrists to pro-worker populists.”

A member of the United Steelworkers Local 795, McCants works at a local manufacturing plant. He is the father of three children, ages 21, 15 and 5, and lives with his wife in Richmond Hill, a suburb of 19,013 outside of Savannah that has doubled in population since 2010. McCants grew up in the Black Belt town of Oglethorpe, the county seat of Macon County, where he served on city council from 2013 to 2018.

McCants is critical of the way the Harris-Walz campaign was managed in Georgia and thinks that the Georgia Democratic Party, unable to see beyond the Atlanta metro area, has forsaken both Black and white rural voters. We asked him what might have been done differently.

How did you get into politics?

I was just watching CNN one day, back in 1998, and I saw Sam Nunn and Max Cleland, two former Georgia Democratic U.S. Senators, doing an interview, and I’m like, “What are they talking about?” I remember the day clearly.

That year, my junior year in high school, I volunteered for Sanford Bishop, the House member for Georgia’s 2nd district. It was something I did on a whim. I started liking it. I liked the retail politics, the hand shaking, the back slapping, the rallies.

Once I got out of high school, I worked on other campaigns until I first ran for office myself in 2013, for city council in my hometown of Oglethorpe, in Macon County, which is in the Black Belt.

No one recruited me. No one told me to do it. I just ran on my own because I saw a need for change in my hometown. It was the same cast of characters. I knew they were all good people, but they just didn’t do anything. I had been going all over the state doing this and that for other candidates and helping other people. So, I thought, why not come home and make a difference in my hometown.

I lost by four votes the first time. But the guy I ran against decided to step down and I was asked if I would take on his term, which I did. I served five years on the city council.

I really got known across rural Georgia because of my blog, Peanut Politics. I was the only Democrat who spoke to rural issues and for rural Democrats as a whole. I managed to build up a solid following. I developed trust among folks running for office and current and former elected officials, especially among Republicans. They’ve been trying to get me to switch over for the last 10 years.

As chair of the Bryan County Democrats, what’s your main takeaway from the election?

It was one of the most disappointing things that I’ve experienced in my 24 years of being an advocate for rural Georgia. It was a debacle.

I’m not surprised by the result. There was no ground game whatsoever from the Harris campaign. There was no get-out-the-vote efforts whatsoever. This was a billion-dollar campaign, and the question being asked right now is where did all that money go? Because it did not make it on the ground here in Georgia. A million dollars would have made the difference in her winning this state.

There’s a lot of anger towards the Harris campaign. There’s anger towards Biden. But a lot of us rural Democrats down here were not surprised by the result because we didn’t see any action from the Harris campaign whatsoever. It was all Atlanta, and Atlanta some more. Harris made one trip to Savannah in late August for a rally, but other than that, it was strictly metro Atlanta.

So what do you think should be done?

There’s an effort right now here in Georgia to remove the current Democratic Party state chairwoman Rep. Nikema Williams. It’s being led by Sen. Jon Ossoff and I understand Sen. Rafael Warnock is behind the effort as well.

But to me, it shouldn’t fall squarely on her shoulders because this is a problem that we’ve been having here for the last 15 years. It’s just different leadership with the same results. So you have calls for a total wipeout of the current leadership and installation of new people on top of the Georgia Democratic Party. But all that will not matter if they don’t get down into the rural areas because this is where the Democratic Party is hurting.

Did you all know that in the Black Belt region of this state President Trump carried four majority Black counties, Washington, Early, Jefferson and Dooly? When I saw that, I knew right then Harris had no shot to win Georgia.

For readers who aren’t familiar with Georgia’s Black Belt, could you explain its significance in state politics?

The Black Belt stretches from Augusta across central Georgia all the way down into the 2nd congressional district, in the southwest. Without support in the Black Belt counties no Democrat can win statewide.

It’s just a fact. The Black Belt was the primary reason why Senators Warnock and Ossoff won their elections in 2020 and 2021. They campaigned in these counties and invested large sums of money.

The Black Belt is largely poor. It’s heavily agricultural. It doesn’t have a lot of income. And it has underperforming school systems. There are a lot of disadvantages in the Black Belt.

But if you go and talk to the voters in these areas, they will show up. And this past Tuesday, they did not show up for Harris because they were not being courted. A lot of these voters just decided to stay home. They’re like, “Nobody’s talking to me. I got the mailer in my mailbox. Yes, Kamala is a black woman, but what is she offering me and my family?”

The thinking was that black voters would just turn out because Kamala is a Black woman. It doesn’t work like that. That was a major miscalculation. You have to work these areas, you have to cultivate these areas.

So where were the decisions made that led to this disconnect? Is it the national campaign? Is it the state party? Is it Atlanta based? Who do you see as being implicated?

It’s a little bit of everything. Ever since former Gov. Roy Barnes (D) lost in 2002, it’s been pretty much an Atlanta-focused state party. And following 2010, when Barnes tried to reclaim the governor’s mansion, there was a full acceleration to the left in the Democratic Party to try to mimic the Democratic National Committee, which was a detriment to us up until 2020 when we had Sens. Ossoff and Warnock win.

But the activists in the state party, the organizers, they are not comfortable around rural people. It’s just a fact. They don’t want to travel to middle Georgia or southern Georgia. They don’t want to spend the time here. They don’t want to invest here. They’ll drive through these areas to get to Savannah or Columbus or Albany, but they will not stop in Swainsboro. They won’t stop in Eastman. They won’t stop in Quitman.

There’s a discomfort amongst the Atlanta crowd with rural folks like myself. We do have rural progressives here. But for the most part, we’re mostly middle of the road or more independent-minded, even the Black Democrats in rural areas like myself. I’m a conservative Democrat. I’m an NRA member. I’m a small business owner. I’m a member of the local Chamber of Commerce down here.

They call Democrats like myself Republican-lites because we don’t adhere to what they believe in Midtown Atlanta. So they look at someone like me, and say, “You don’t believe in that. You’re a Republican, kid. You’re not one of us.” I’ve heard that for many years. But it’s voters like myself they continue to lose each election cycle. And they need voters like me to remain in the party, Black males in particular, because if we continue to leave the Democratic Party, the state party is going to be in trouble. I haven’t left the Democratic Party, but I’ve given some thought to becoming a full-fledged independent because of what happened.

I don’t care that the majority of the population is located in and around Atlanta. Georgia is not like Virginia, where if you carry northern Virginia and you pretty much win the state. It’s not Pennsylvania where you carry the eastern part of the state and Pittsburgh. You must have a winning coalition here in Georgia. You’ve got to get those rural Black Belt counties if you’re going to win statewide.

And right now, until they show a willingness to come down here to invest and to campaign and to talk to us, it’s going to be the same old song.

We don’t have tall buildings down here. We don’t have Starbucks. We don’t have the latest things that metros have. But we do matter. Rural voters do matter.

What did you think of Obama coming down to Atlanta to encourage black men to vote for Harris?

It really didn’t have any effect on Black men because down here the majority of Black men who did vote, the ones that I know, they voted for Trump.

They voted for Trump because he came across as strong and masculine.

The Democratic Party here in Georgia has to move away from being this very soft and sensitive-to-everything party that they’ve become, or they’re going to continue to bleed male voters. It’s a party that has been catering to female voters. Let a man be a man. White male voters left a long time ago. Black male voters are not leaving in droves, but a little bit by a little bit each cycle. They’re not necessarily going Republican, but they’re going independent.

I understand women out vote men, but everything you heard, especially in the Harris campaign, even out here in Georgia, it’s all geared towards women in the suburbs, Black women, who are the backbone of Democratic Party.

And then you’re focusing on voters who hardly vote. These are low-income, low-information voters who don’t bother to vote but are the main ones who complain about what’s being taken away and what’s being cut.

That’s been my frustration for a long time with the Democratic Party. We always try to care for the downtrodden and the less fortunate, and I understand that, but, I’m just being real with you all, those voters just don’t vote.

You can have barbecues all day long, and fish fries. You can bring celebrities in, like Harris did, and these people still don’t vote. So my thinking is, why waste all your time?

What did you think about the Harris campaign’s messaging around the economy?

She had a good message, but the messenger was the issue. She just wasn’t able to make the sale. She wasn’t able to convince voters that, yes, I’ll be better for your pocketbooks.

And then there was her inability, her unwillingness, to distance herself from President Biden. She could have come out and said, “I would have done this differently if I were president.” That cost her a lot.

Here in Richmond Hill, the Trump campaign had all these signs along Interstate I-95, “Trump low prices. Kamala high prices.” They resonated. It was simple.

If you were head of the Georgia Democratic Party what would your agenda be?

They need to get back to being the party of the working-class men and women in this state, and not worry so much about these cultural issues like transgender people playing sports and what bathroom they go into. Those are the issues that torpedoed the Democratic Party. That’s not to say they’re not important, but they put those issues first and foremost at the expense of families like myself, young families who work every day. We’re not concerned about that. If it was me, I would bring this party away from cultural-identity politics into a more bread-and-butter, kitchen-table issue related party. We used to be a party like that in the 1990s, in the early 2000s.

We’ve gone so far to the left, trying to appease the left flank because they have the money. They’re the ones who fund the candidates like Stacey Abrams. And I like Stacey Abrams, but a lot of her money came from groups like that and she came out here pushing issues that don’t appeal to mainstream Georgians. And if candidates don’t push those issues, then they’ll cut you off financially and you’re at a disadvantage against your Republican counterparts.

I would also stress better candidate recruitment because our recruitment here in Georgia has been abysmal for the last decade. We just had some of the worst candidates run for office.

What about the labor movement and support for union organizing? Is that something that would resonate in rural Georgia?

It doesn’t because outside of the cities, the unions are not that big of an influence here in Georgia. It doesn’t carry the same weight as up in Michigan or Pennsylvania. Although I’m a union member, the United Steel Workers, up in Savannah.

What about the role of the churches in Georgia? According to the exit polls White evangelicals comprised 29% of the Georgia electorate and 92%of them voted for Trump.

Religion plays a major role in the rural areas. I’m a Southern Baptist. The Democrats at one point used to be the party that paid attention to what I call the Christian vote or the value voter. The party has gotten away from that.

Again, it’s all about a comfort level. The left flank of the party doesn’t understand that faith plays a big part in life across rural Georgia. If you’re not willing to learn about why our faith is very important to us Democrats who believe in God—I don’t care what anybody says, we believe in our Lord and Savior—it’s sad me. That’s where we’ve come up short as a party.

What do you see as the strategy for rebuilding the trust of rural voters in Georgia?

First and foremost, we should install a new leader of the state Democratic Party. I have my pick. I like John Barrow, former congressman in the 12th district. He lost to Rick Allen in 2014.

Barrow is a rural Democrat, and he still has an apparatus in place from his statewide run in 2018 for Secretary of State and from his campaign for the Georgia Supreme Court this year. He would be able to rebrand the Democratic Party and turn the page from the old to the new. He understands rural Georgia, he understands our way of life. He understands our politics, what will work, what won’t work. And most importantly—I’m just going to say it—he’s white.

The Democratic Party has become too Black and too urban. A lot of white moderates have gone to the Republican Party as a result. They think, the Democratic Party is for Black people.

These are conversations that I have on a daily basis. They say, “The Democratic Party—and, Keith, I like you, and I’ll vote for you in a minute—but your party, they are only concerned about different identity groups, and we white voters don’t have a place unless we’re white and we’re liberal.”

That notion of Georgia Democratic Party being too Black, it’s true. If you look at our state legislature, for example, we only have one rural white Democrat left in the entire state. That’s Debbie Buckner over in Johnson County, who is in the State House. In the State Senate, we have zero.

So as much as the Democratic Party talks about diversity, if you don’t have any whites in the party, I don’t call that diverse.

The Democratic Party has an image problem, a branding problem, and it’s going to take someone who knows how to really shake off those connotations.

I’ve heard that Keisha Lance Bottoms, the former mayor of Atlanta, is someone that’s being pushed to take over the Democratic Party, and I like Keisha Lance Bottoms, but she’s not the right pick at this time. She’s still from Atlanta.

If she, or whoever, is willing to travel to these different counties and listen to concerns of Democrats who don’t live in the cities, then they’ll get a better understanding of what’s wrong, how to deal with it, and how to craft a message that appeals to all Georgians—not a message that just appeals to their friends in Atlanta or Gwinnett County, Cobb County or Clayton County, but to everybody: metro Atlanta, south Georgia, down around White Cross, around the swamps, around the Wild Grass region of south central Georgia, the peanut fields. But it’s not going to be fixed overnight. These problems have been here with us for a long time.

The Democratic Party has to listen to the people on the ground, the people who are at their kitchen tables every night and not the elites who are living the good life. Until they get back to being the party of Jefferson and Jackson, it’s going to be a tough row to hoe.

What advice would you give a young person in rural Georgia, who like you 26 years ago, wants to get involved in politics?

I would tell him or her, don’t wait for someone to tell you to do something. If it’s in your heart to do something like this, then go for it, step up. The rewards will outweigh the negative aspects of it.

But it takes work, it takes time, it takes commitment, it takes dedication. And, it took me over 20 years to get to this point, and it’s not easy.

Go with your gut and don’t worry about it. People are gonna talk about you regardless of what you do, whether it’s good or bad. I had a lot of that: “Kid, you don’t know what you’re doing. You don’t know what you’re talking about.”

If you feel that sense of urgency within you to make a difference in your community like I did, then you go for it. And chances are most times you will be successful.

The post As Goes the Black Belt, So Goes Georgia appeared first on Barn Raiser.