This county is California’s harshest charging ‘desert’ for electric cars. Local activists want to change that

Lea esta historia en Español

Few places in California are as unforgiving for driving an electric car as the remote and sparsely populated Imperial Valley.

Only four fast-charging public stations are spread across the valley’s vast 4,500 square miles just north of the US-Mexico border, according to the U.S. Department of Energy. That means if you’re Greg Gelman — one of only about 1,200 Imperial County residents who own an electric car — traveling almost anywhere is a maddening logistical challenge.

“It’s been, I won’t say a nightmare, but it’s been very, very, very inconvenient,” Gelman said on a recent afternoon as he charged his all-electric Mercedes-Benz at a charging station in a Bank of America parking lot in El Centro. “Would I do it again? No.”

California’s electric charging “deserts” like the Imperial Valley pose one of the biggest obstacles to the state’s efforts to combat climate change and air pollution by electrifying cars and trucks.

Experts say the slow installation of chargers in California’s remote regions could jeopardize the state’s phaseout of new gas-powered cars. Under the state’s mandate, 35% of sales of 2026 models must be zero-emissions, ramping up to 68% in 2030 and 100% in 2035.

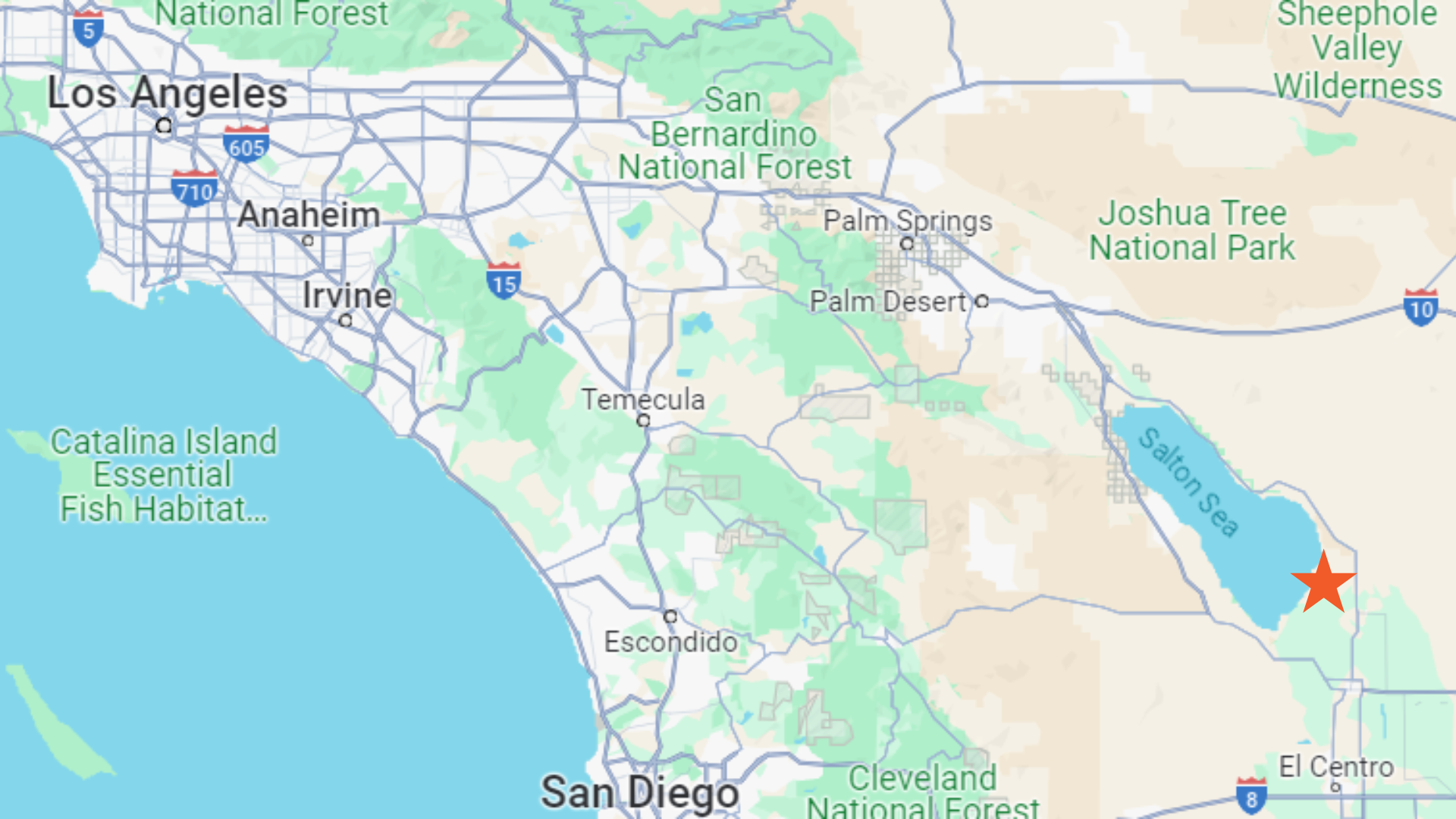

Nestled in the desert in California’s far southeast corner, Imperial County ranks dead last in electric car ownership among California counties with populations of 100,000 or more, according to a CalMatters analysis of 2023 data. Only 7 out of every 1,000 cars are battery-powered there, compared with 51 out of every 1,000 statewide.

High poverty and unemployment are a major factor in the region’s slow transition to electric cars, but its lack of public chargers are a big drawback, too.

People living in rural, low-income regions like the Imperial Valley have the least access to electric car chargers, according to a state Energy Commission analysis. More than two-thirds of California’s low-income residents are a 10-minute drive or longer from a publicly available fast charger.

Luis Olmedo, executive director of El Comite Civico del Valle, a nonprofit advocating for environmental justice, has battled for years against the Imperial Valley’s unhealthy air. Now he is making a bid to become its go-to supplier of charging stations for zero-emissions cars.

Olmedo isn’t waiting for businesses or the state to make chargers a reality in Imperial County. Instead, his group has embarked on a $5-million, high-stakes crusade to build a network of 40 fast chargers at various locations. It’s an open question whether his somewhat quixotic endeavor will succeed.

Electric car chargers “are an opportunity for us to be able to breathe cleaner air,” Olmedo said. “It’s about equity. It’s about justice. It’s about making sure that everybody has chargers.”

Esther Conrad, a researcher at Stanford University who focuses on environmental sustainability, said getting chargers in places like Imperial County is critical to California’s effort to transition to electric vehicles in an equitable way. Apartment dwellers and others who don’t have charging at home need nearby and reliable places to charge.

“When you have a rural community that’s low-income and distant from other locations, it’s incredibly important to enable people to get places where they need to go,” Conrad said.

Hours from urban centers

A car is essential for traversing Imperial County, which is the most sparsely populated county in Southern California.

Its neighborhoods are vast distances from urban centers that provide the services that residents need: El Centro — its biggest town, home to about 44,000 people — is much closer to Mexicali, Mexico, than it is to San Diego, which is about a two-hour drive away, or Riverside, nearly three hours. Its highways and roads cross boundless fields of lettuce and other crops that give way to strip malls, apartments and suburban tracts — and then even more crops and open desert.

If you drive an electric car the 109 miles from El Centro to Palm Springs, your route takes you through farmland, desert and around California’s largest lake, the Salton Sea, which is also one of its biggest environmental calamities.

The Salton Sea has been receding in recent years, causing toxic dust to blow into Imperial Valley towns. The region’s air quality is among the worst in the state, with dust storms and a brown haze emanating from agricultural burning and factories in the valley or from across the border in Mexicali, a city of a million people.

About 16% of Imperial County’s 179,000 residents have asthma, higher than the state average. The air violates national health standards for both fine particles, or soot, as well as ozone, the main ingredient of smog; both pollutants can trigger asthma attacks and other respiratory diseases.

More than 85% of Imperial County’s residents are Latino, and Spanish is widely spoken here. Agriculture is a major employer, and many businesses are dependent on cross-border trade and traffic from Mexico. The county’s median household income is $53,847, much lower than the statewide median, and 21% of people live in poverty.

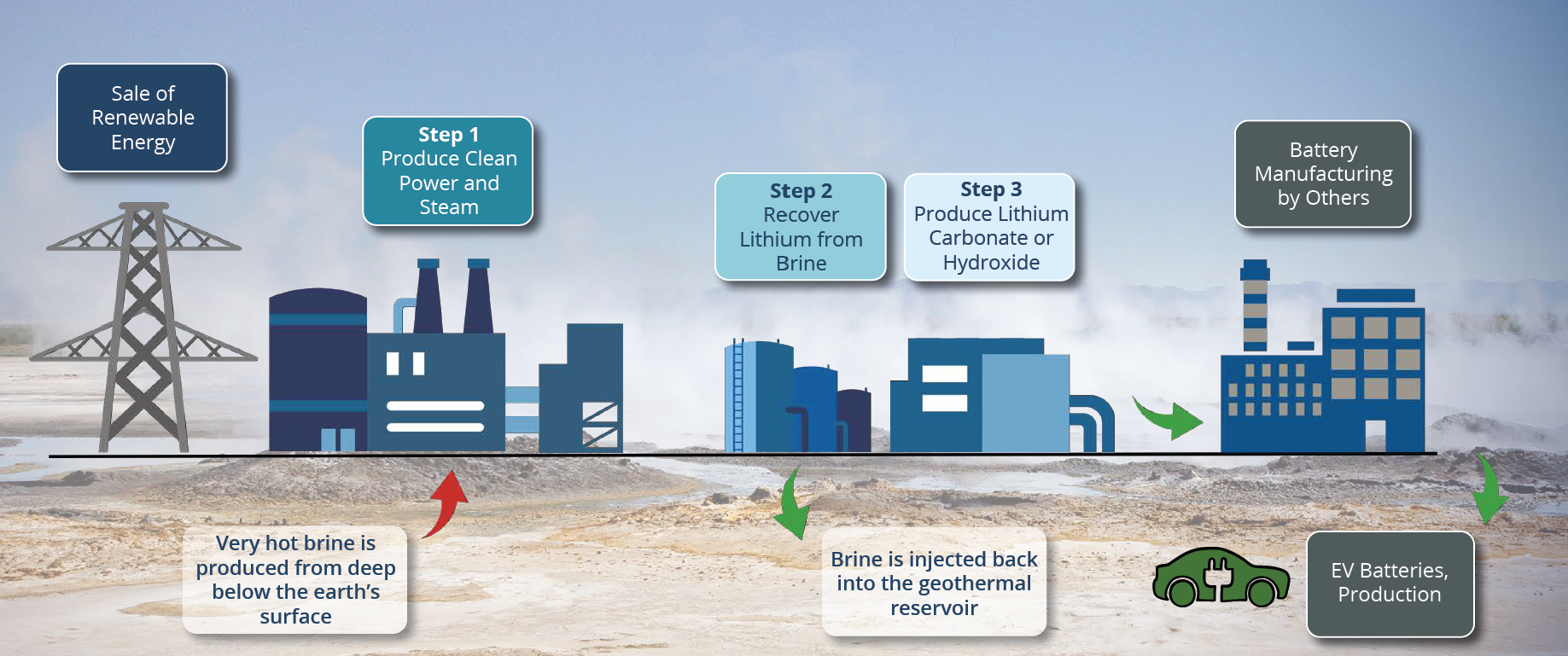

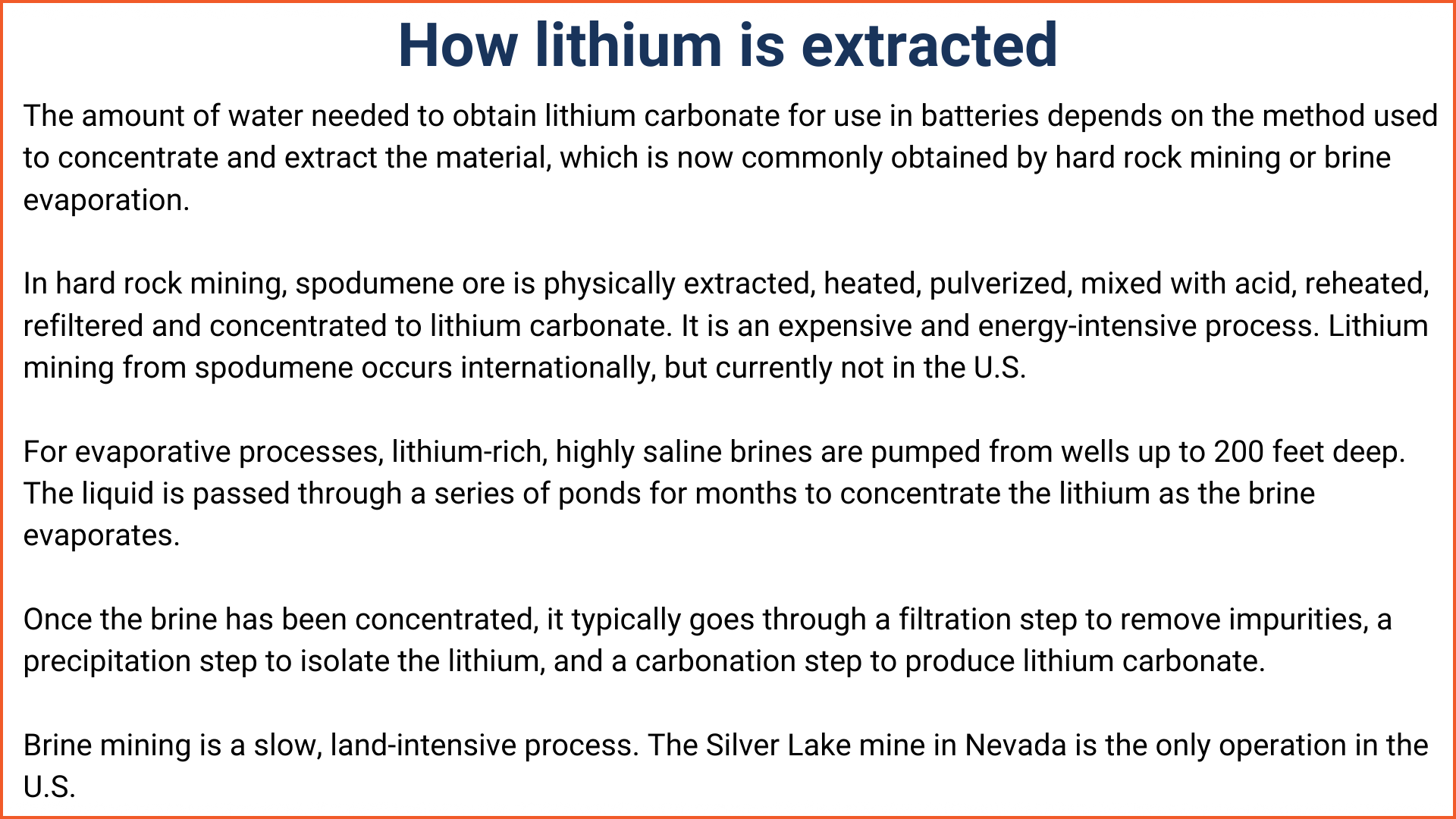

Now the discovery of lithium, used to manufacture EV batteries, at the Salton Sea has the potential to transform the region’s economy. State officials say the deposit could produce 600,000 tons a year, valued at $7.2 billion, and assist the U.S. as it tries to foster a domestic electric car industry that rivals China’s.

But Olmedo worries that when the mineral is removed from the valley, it won’t meaningfully change people’s livelihoods or their health. He points to examples in the developing world where local people have been left behind as extractive industries take what they need.

“We’re about to extract, perhaps, the world’s supply of lithium here, yet we don’t even have the simplest, the lowest of offerings, which is: Let’s build you chargers,” Olmedo said.

Chicken and egg: Too few EVs and too few chargers

Last year, electric cars were only 5% of all new cars sold in Imperial County, compared with 25% statewide. Getting chargers into low-income and rural places will become more and more important as California struggles to meet its ambitious climate targets.

The Energy Commission estimates that California will need 1.01 million chargers outside of private homes by 2030 and 2.11 million by 2035, when more than 15 million electric cars are expected on the roads. So far the state has only about 105,000 nonprivate chargers.

Nick Nigro, founder of Atlas Public Policy, which researches the electric car market, said charging companies won’t locate chargers in regions with few electric vehicles.

“You need revenue, and if the EVs aren’t there, then your customers aren’t necessarily there, so you do have a legitimate chicken and egg problem,” Nigro said. “We have to look to public policy to help that market failure.”

The Biden administration will invest $384 million in California’s electric car infrastructure over five years. And state officials are investing almost $2 billion in grants for funding zero-emission vehicle chargers over the next four years, including some special grants in rural, inland areas for up to $80,000 per charger. Olmedo says the funding has been insufficient so he’s had to turn to donations and other sources of funding.

Patty Monahan, one of five members of the California Energy Commission, said “it’s particularly important that we see chargers” in the Imperial Valley and other low-income counties with poor air quality.

Imperial Valley has only four fast-charging stations open for public use, where chargers are capable of juicing batteries up to 80% in under an hour, according to the U.S. Department of Energy. Three are in El Centro, with one exclusively for Teslas; another is in the border town of Calexico and was recently installed by El Comite. Six other stations offer only slower chargers.

Olmedo envisions a network of 40 publicly accessible chargers throughout the valley. El Comite is expecting funding from the California Energy Commission, and has received donations from Waverley Streets Foundation, the United Auto Workers and General Motors. The group is seeking more state funding.

Olmedo acknowledged that he is facing a slew of challenges with his project, including some local opposition and the high cost of installation and maintenance.

At a warehouse in the city of Imperial where El Comite stores the chargers, Jose Flores, project manager for the group’s charging initiative, said he and three colleagues spent four days in Santa Ana, about 200 miles north, at a facility managed by BTC, the company that makes the chargers that El Comite is installing.

They received training on installation and maintenance techniques, and discussed how not all chargers can be used by all electric vehicles. He learned about payment and cooling systems, and that the chargers might need more frequent maintenance because of Imperial Valley’s harsh desert conditions.

“We’re like a testing ground because we have poor air quality here due to the Salton Sea and being in a desert,” he said.

El Comite installed its first charger at its Brawley headquarters in 2022. Last December, El Civico pressed ahead with a more ambitious project: Four of their fast chargers are now operating in a park in the border town of Calexico.

Chris Aldaz, 35, a U.S. Postal Service worker who lives in Calexico, charges at home, but at times uses chargers at the group’s Brawley headquarters that people can use for free. It is a Level 2, which can take several hours to charge.

“The reason why I wanted to get an EV was that it was cheaper,” Aldaz told CalMatters. “I don’t want to be spending all this money on gas, and on maintenance, and it was better for the environment.”

Nevertheless, Olmedo’s electric car chargers have become a local political issue.

Maritza Hurtado, Calexico’s ex-mayor, and coordinator of a City Council recall campaign, said it was inappropriate for El Comite to have built four electric car chargers in a downtown park. The chargers were a distraction “from our police needs and our actual community infrastructure needs,” Hurtado said at a public hearing at the county’s utility, the Imperial Irrigation District, in January. She declined to speak to CalMatters.

“We had no idea they were going to take our parkland,” Hurtado said at the hearing. “It is very upsetting and disrespectful to our community for Comite Civico to come to Calexico and take our land.”

Olmedo hopes that the chargers ultimately will be something the county’s Latino community takes pride in.

“Put this in perspective: It’s a farmworker-founded organization, an environmental justice organization, that is building the infrastructure. It’s not the lithium industry. It’s us, building it for ourselves.”

Data journalist Erica Yee contributed to this report.

This county is California’s harshest charging ‘desert’ for electric cars. Local activists want to change that is an article from Energy News Network, a nonprofit news service covering the clean energy transition. If you would like to support us please make a donation.