Native vote could prove critical in Montana U.S. Senate race

For help on Election Day, contact the Native American Rights Fund’s helpline at 866-OUR-VOTE (866-687-8683) for election protection volunteers who can assist voters in Indian Country. The organization can also be reached at vote.narf.org.

Kolby KickingWoman

ICT

MISSOULA, MT — One of the most crucial and hotly contested races outside of the presidency this election cycle has been taking place in Montana.

Incumbent Democratic Sen. Jon Tester is locked in a tight contest with Republican challenger Tim Sheehy in a race that could determine which party ultimately controls the U.S. Senate.

The Native voting bloc could prove to be critical this year in determining the outcome.

SUPPORT INDIGENOUS JOURNALISM. CONTRIBUTE TODAY.

There are 65,000 eligible Native voters in Montana, but more than 35,000 – more than half – were not registered to vote, according to Sami Walking Bear, Crow, who is the outreach and field director for Western Native Voice Votes, the sister organization to Western Native Voice.

Walking Bear hit the ground in February with a goal of registering 10,000 people, and by June had more than 30 community organizers across the state on the seven reservations and urban areas of Billings and Great Falls.

Along with traditional door-to-door canvassing and phone banking, she has organized small events like bingo nights to reach people.

“During the bingo games, we would put in a lot of information about voting in the upcoming election and just tips on how to register to vote, and that we offer assistance in any way we can to help you register to vote,” Walking Bear said. “So a lot of our organizing had a lot to do with events and trying to draw people to us.”

A lot of people were hesitant when she approached them “with a piece of paper from the government asking them to sign it.” She gave an example of someone who may have a warrant wondering if the cops would find them if they registered to vote.

“We worked really hard,” she told ICT. “We ended up getting about 3,300 registered voters. That was, we thought, pretty good, and now we’re hoping we have 70 percent turnout for elections.”

Nationally, there has been much focus on the issues of immigration and the economy, but issues to Native voters can be different, including protecting tribal sovereignty, conservation and healthcare.

The race between Tester and Sheehy drew increased attention from Native voters when Sheehy was caught in hot water in August after derogatory comments about the Crow Reservation were made public by the Char-Koosta News, the news publication of the Flathead Indian Reservation.

Sheehy has also drawn fire after claiming to have been wounded in military service despite telling a park ranger that the wound was self-inflicted.

Letting Native people ‘drive the bus’

Tester, 68, an organic farmer, has worked closely with tribal communities during his tenure in the U.S. Senate.

He was instrumental in the passage of water compacts for the Confederated Salish and Kootenai Tribes in 2020 and the Fort Belknap Indian Community in 2024. He voted for passage of Savanna’s Act, which improves coordination with tribes and enhances law enforcement’s ability to track and prevent crimes against Native Americans.

Democratic U.S. Sen. Jon Tester of Montana speaks during a hearing of the Senate Committee on Veterans’ Affairs on Capitol Hill in Washington, D.C. in this file photo taken on Sept. 26, 2018. Tester is facing a stiff challenge from Republican businessman Tim Sheehy in the Nov. 5, 2024, election. (AP Photo/Alex Brandon)

Tester has also served on the Senate Committee on Indian Affairs and the Veterans Affairs Committee. He is often quoted as saying, “We need to let the Native Americans drive the bus,” when it comes to issues facing tribal communities.

Tester worked two years as a music teacher starting in 1978 before returning to run the family farm and butcher shop near Big Sandy, Montana. After holding several local positions, he won election to the Montana Senate in 1998, and worked his way up to become the chief presiding officer.

Faced with term limits in the Montana Senate, he won election to the U.S. Senate in 2006. He is seeking his fourth term this year.

Jonas Rides At The Door, Blackfeet, is a Marine Corps combat veteran and Purple Heart recipient from Missoula who served in the Iraq War. He said Tester has been an ally with a good record with Native veterans.

Rides At The Door hopes there is big Native turnout on Election Day.

“We can be the change, get out and vote and change this election,” he said.

Controversial remarks

Sheehy, 38, a former Navy Seal, is a businessman who founded Bridger Aerospace, an aerial firefighting and wildfire management company that is based in Belgrade, Montana. He also co-founded a cattle company that produces Montana beef.

He has drawn sharp criticism over the remarks he made during public events that were recorded on audio.

In the clips, Sheehy is heard saying that as a rancher, he is involved on the Crow Reservation, and that roping and branding is “a great way to bond with all the Indians while they’re drunk at 8 a.m.”

Additionally, at a different event, he said that while participating in the Crow Fair parade, “They’ll let you know when they like you or not, if Coors Light cans flying by your head… They respect that.”

The comments were quickly condemned by tribal leaders throughout the state, who called for him to apologize. The Democratic members of the Montana American Indian Caucus expressed their disappointment with the comments as well, saying the remarks perpetuate racist stereotypes.

Republican businessman Tim Sheehy is challenging incumbent Democratic U.S. Sen. Jon Tester in the Nov. 5, 2024, election. Here, he addresses suppoters at a primary election night party in Gallatin Gateway, Montana, on June 4, 2024. (Thom Bridge/Independent Record via AP)

“The Montana American Indian Caucus cannot express how let down we are by your remarks, where we can hear you disparaging the Crow Nation,” the caucus said in a statement. “Your words perpetuate the damaging and racist stereotype of ‘the drunken Indian.’ This stereotype, and others like it, hurts our young people and contributes to limitations on their opportunity to succeed…Your words are wrong, derogatory, and hurtful to a racial population that is fighting for equality and to improve their homeland.”

During a debate between the two candidates, Tester called for an apology. Sheehy didn’t explicitly apologize but did take accountability for the comments.

“The reality is, yeah, insensitive,” Sheehy said. “I come from the military, as many of our tribal members do. You know we make insensitive jokes and probably off-color sometimes, and you know, I’m an adult, I’ll take accountability for that, but let’s not distract from the issues that our tribal communities are suffering.”

Sheehy has also drawn questions about a bullet wound in his arm, which he said came from a firefight while he was serving in Afghanistan. Glacier National Park Ranger Kim Peach, however, said Sheehy told hospital officials in 2015 that he had been injured by an accidental discharge of his weapon in the park.

The park ranger repeated the accusation in an advertisement from a pro-Tester political action committee, but acknowledged that the ad had been recorded before he spoke publicly about the allegations. Republicans said the ranger is not credible.

“He’s shifting his story left and right because he is a liar and a Democrat partisan,” said Mike Berg with the National Republican Senatorial Committee, according to The Associated Press.

Tester said Sheehy should release his medical records to clear up the dispute, adding: “Stolen valor is a huge problem.”

Follow the money

The race has drawn a major influx of campaign funding.

Democrats, fighting to keep the majority in the Senate, are on track to outspend Republicans by almost $50 million in the Montana race, according to Federal Election Commission filings and the media tracking firm AdImpact.

Total spending is expected to exceed $315 million, or about $487 for each of the state’s 648,000 active registered voters — a record for a congressional race on a per-voter basis, according to party officials.

The Associated Press reported that much of the money traces back to shadowy political committees with wealthy donors. The non-partisan Campaign Legal Center sued over alleged financial transparency violations by a pro-Tester group, Last Best Place PAC, that has amplified some of the claims against Sheehy. Another complaint says the advocacy group used a straw donor to conceal more than $2.5 million in contributions to political committees, including one supporting Sheehy.

A Sheehy victory could shift the balance of power to Republicans.

This story contains material from The Associated Press.

Like this story? Support our work with a $5 or $10 contribution today. Contribute to the nonprofit ICT. Sign up for ICT’s free newsletter.

Texto: Carlos Torres Bujanda

Texto: Carlos Torres Bujanda

Por Johani Carolina Ponce (colaboración especial para Conecta Arizona).

Por Johani Carolina Ponce (colaboración especial para Conecta Arizona). TIM WALZ, LIDER EN ENERGIA LIMPIA Y POLITICAS CLIMATICAS

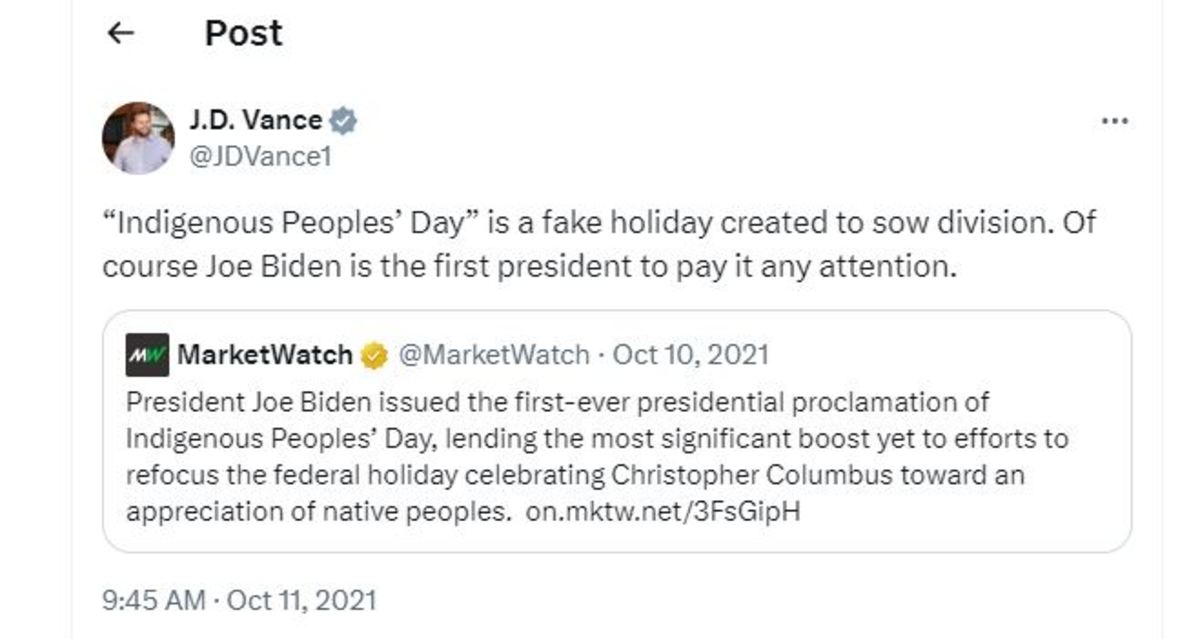

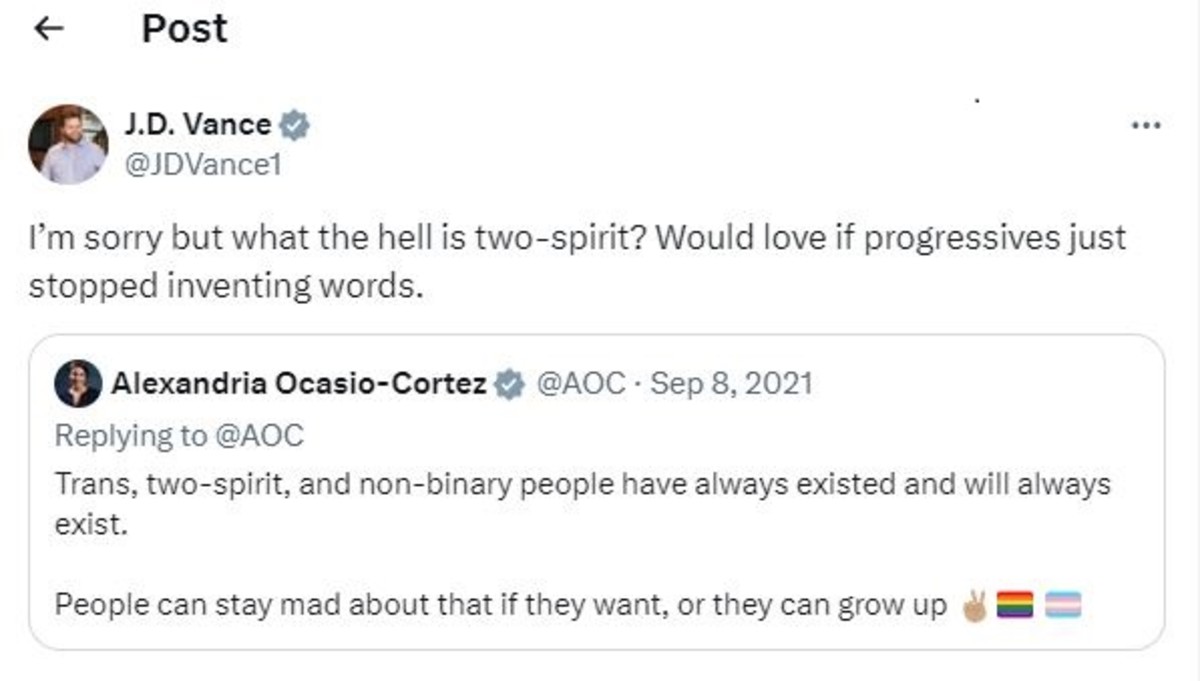

TIM WALZ, LIDER EN ENERGIA LIMPIA Y POLITICAS CLIMATICAS  TRANSFORMACIONES AMBIENTALES EN LA CANDIDATURA DE J.D. VANCE

TRANSFORMACIONES AMBIENTALES EN LA CANDIDATURA DE J.D. VANCE