Trump directive creates chaos on the Colorado River

Daniel Herrera Carbajal

ICT

In March, Gila River took out 10,000 acre-feet of their allotted water from Lake Mead after the Trump administration’s Unleashing American Energy executive order froze money for any program related to the Inflation Reduction Act. The act, which Congress passed during the Biden Administration in 2022, allocated money for tribes and states in exchange for giving up some of their shares of Colorado River water.

The Trump administration later unfroze the Inflation Reduction Act funds that would be used for water conservation projects and to build canals. The act allocated around $4 billion to compensate tribes, states and other organizations to not take water out of the Colorado River to use to generate revenue like crops.

Gila River Governor Stephen Roe Lewis wrote a letter to the Interior Secretary Doug Burgum on Feb. 11 before removing Colorado River water from Lake Mead.

“We have given the department every opportunity to avoid what could be a calamitous break in our longstanding partnership, with terrible consequences for the entire basin,” he said.

If water levels continue dropping, hydroelectric dams on the Colorado River will not be able to generate electricity. But the compensation to not take water out of the river has been seen as a short-term solution by many experts, including Mark Squillace, a professor of law at the University of Colorado Boulder who specializes in natural resource law.

“My concern is that the Biden administration seemed to be focused on short-term buyouts of water consumption,” he said. “I just don’t think that kind of approach is sustainable. What we need on the Colorado River are permanent reductions in consumption, and so spending a lot of money to temporarily buy out the rights of people to use all of their water, right, is just not something that is going to solve the problem.”

Thirty tribes have rights to the Colorado River. The river is a resource, but for the Zuni Pueblo it is the source of life.

“For the Zuni people, the Colorado River is really important because the river and the Grand Canyon are our homeland. That’s where the Zunis emerged,” said Councilman of Zuni Pueblo Edward Wemytewa.

The Colorado River has important cultural significance to each tribe that has water rights to it, but the Colorado River compact that outlined how the river would be divided was not drafted in consultation with tribes.

“Laws were created by the US governments, by the US agencies, and during those times, the federal government, in the name of public interest, they started delineating territories. They start creating laws about water usage, water compacts,” said Wemytewa. “Well, in those earlier years, when the laws were being developed and implemented, the Zuni was not at the table. Many Native peoples weren’t at the table.

“Under federal law, those tribes have the right to take their water, usually in priority over everybody else, because the date of priority for Indian water rights is the date of their reservations, which is typically within the 19th century,” said Squillace. “So those water rights tended to date back before other non-Indian users.

“Those are legal rights that they are entitled to. And so one of the things I’ve suggested in my article is that maybe we should think about closing down the river to new appropriations. Why are we continuing to appropriate new water rights when we have this crisis and we have early water rights from Native American tribes that are currently legal but not being utilized for a number of different reasons?” he said.

The current compact being used was created in 1922, and it divided the river into two basins – upper and lower.

Each basin was allotted no more than 7.5 million acre-feet of water per year, equaling 15 million acre-feet of water each year. Mexico was also allocated 1.5 million acre-feet a year. The amount of water the river produces was vastly overestimated at the time of the compact’s creation.

“At the time that they negotiated the compact, it was thought that there was maybe 18 million acre feet of water on an annual basis in the river, which turned out not to be true,” said Squillace.

Currently, the Colorado River is producing about 12.5 million acre-feet a year. A vast over-allocation of water has led to states battling over water and how to use it.

Squillace proposed a new Colorado River compact. It proposes to update states’ water usage laws and to bring tribal nations into the conversation.

“I’ve suggested that maybe we could come up with a new compact, which would look very different from the current compact, but would basically be an agreement among the states to modernize their water laws,” he said. “Right now we have a number of principles in the various state water laws that I think allow for, I don’t want to call them wasteful, but at least inefficient uses. We could increase our efficiency in terms of the amount of water that we use if we sort of refined what we call beneficial use. There’s a principle in western water law that you only get as much water as can be beneficially used.”

For the Zuni Pueblo, a history of strong-handed negotiations and a lack of knowledge of a government system that is not their own led to signing deals that did not benefit them.

“When there were any land settlements or water settlements, tribes were never provided attorneys.Tribes were never given a heads up, They were never given funding to educate ourselves as Indigenous peoples,” Wemytewa said. “We are stewards of the water. We find the corn seed central. The corn seed is central. In fact, our abstract name is Children of Corn because we’re farmers, we’re agricultural people. What agricultural people would give up their water rights? What agricultural people would give up their watershed? We didn’t have much choice.”

Tribes have priority over everyone else when it comes to their water rights pertaining to the Colorado River, which means they must have a voice in the conversation.

“There are 30 Native American tribes with water rights along the Colorado River. And it may be impractical to basically have all 30 tribes represented during negotiations. We’ve got seven states, two countries, 30 tribes. That would be a very difficult kind of negotiation,” he said.

“But you could certainly have some representatives. The reason it’s tricky is that not all tribes agree on the best approach here. And so it’s important that we treat individual Native American tribes as people who can have their own views that might be different from other tribes. And so how do you ensure fair representation of all the tribal views without actually putting all those tribes at the table during negotiation?”

For Wemytewa, a new compact with tribes involved is necessary.

“Today, as a tribal leader, I submit comments to federal agencies, whether it’s the National Park Service or the Bureau of Land Management or (U.S. Geological Survey). We submit our comments trying to provide guidance to the federal agencies that you have to consider that you can’t continue to open up the lands. You cannot continue to give away water, because by doing so, you continue to remove Indigenous peoples from their aboriginal lands to make room for other people, other cultures.”

Our stories are worth telling. Our stories are worth sharing. Our stories are worth your support. Contribute $5 or $10 today to help ICT carry out its critical mission. Sign up for ICT’s free newsletter!

Feds planning nearly 25 miles of new border wall near Coronado National Forest

‘People would die’: As summer approaches, Trump is jeopardizing funding for AC

The summer of 2021 was brutal for residents of the Pacific Northwest. Cities across the region from Portland, Oregon to Quillayute, Washington broke temperature records by several degrees. In Washington, as the searing heat wave settled over the state, 125 people died from heat-related illnesses such as strokes and heart attacks, making it the deadliest weather event in the state’s history.

As officials recognized the heat wave’s disproportionate effect on low-income and unhoused people unable to access air conditioning, they made a crucial change to the state’s energy assistance program. Since the early 1980s, states, tribes, and territories have received funds each year to help low-income people pay their electricity bills and install energy efficiency upgrades through the Low Income Home Energy Assistance Program, or LIHEAP. Congress appropriates funds for the program, and the U.S. Department of Health and Human Services, or HHS, doles it out to states in late fall. Until the summer of 2021, the initiative primarily provided heating assistance during Washington’s cold winter months. But that year, officials expanded the program to cover cooling expenses.

Last year, Congress appropriated $4.1 billion for the effort, and HHS disbursed 90 percent of the funds. But the program is now in jeopardy.

Earlier this month, HHS, led by Secretary Robert F. Kennedy, Jr., laid off 10,000 employees, including the roughly dozen or so people tasked with running LIHEAP. The agency was supposed to send out an additional $378 million this year, but those funds are now stuck in federal coffers without the staff needed to move the money out.

LIHEAP helps roughly 6 million people survive freezing winters and blistering summers, many of whom face greater risks now that the year’s warm season has already brought unusually high temperatures. Residents of Phoenix are expected to have their first 100 degree high any day now.

“We’re seeing the warm-weather states really coming up short with the funding necessary to assist people in the summer with extreme heat,” said one of the HHS employees who worked on the LIHEAP program and was recently laid off. Losing the people that ran the program is “absolutely devastating,” they said, because agency staff helped states and tribes understand the flexibilities in the program to serve people effectively, assistance that became extremely important with increasingly erratic weather patterns across the country.

In typical years, once Congress appropriates LIHEAP funds, HHS distributes the money in the fall, in time for the colder months. States and other entities then make critical decisions about how much they spend during the winter and how much they save for the summer.

The need for LIHEAP funds has always been greater than what has been available. Only about one in five households that meet the program’s eligibility requirements receive funds. As a result, states often run out of money by the summer. At least a quarter of LIHEAP grant recipients run out of money at some point during the year, the former employee said.

“That remaining 10 percent would be really important to establish cooling assistance during the hot summer months, which is increasingly important,” said Katrina Metzler, executive director of the National Energy and Utility Affordability Coalition, a group of nonprofits and utilities that advances the needs of low-income people. “If LIHEAP were to disappear, people would die in their homes. That’s the most critical issue. It saves people.”

In addition to Washington, many other states have expanded their programs to provide both heating and cooling programs. Arizona, Texas, and Oregon now offer year-round cooling assistance.

HHS staff plays a crucial role in running LIHEAP. They assess how much each state, tribe, and territory will receive. They set rules for how the money could be used. They audit local programs to ensure funds are being spent as intended. All that may now be lost.

But, according to Metzler, there are some steps that HHS could take to ensure that the program continues to be administered as Congress intended. First, and most obvious, the agency could reinstate those who were fired. Short of that, the agency could move the program to another department within HHS or contract out the responsibilities.

But ultimately, Metzler continued, LIHEAP funds need to be distributed so those in need can access it. “Replacing the federal Low Income Home Energy Assistance Program is a nearly impossible task,” she said. States “can’t have enough bake sales to replace” it.

This story was originally published by Grist with the headline ‘People would die’: As summer approaches, Trump is jeopardizing funding for AC on Apr 11, 2025.

Comunidades nativas americanas se manifestaron ante el Capitolio de Arizona: “Las mujeres tenemos 10 veces más probabilidades de sufrir violencia”

Federal Funding Freeze Hurts Local Nonprofits

Borderlands Restoration Network, Tucson Bird Alliance and other local nonprofits are scrambling to understand the impact of the January federal funding freeze imposed by the Trump administration on their programs.

The post Federal Funding Freeze Hurts Local Nonprofits appeared first on Patagonia Regional Times.

‘Finally Free’: Leonard Peltier heads home to North Dakota

ICT Staff

Leonard Peltier is free at last.

The longtime American Indian Movement activist was released Tuesday from federal prison in Sumterville, Florida, after 49 years behind bars in what he has long maintained was a wrongful conviction in the deaths of two federal agents during a 1975 standoff at Pine Ridge.

“Today I am finally free!” Peltier said in a statement released by NDN Collective, which has led the recent effort to win his release from prison. “They have imprisoned me but they never took my spirit!”

SUPPORT INDIGENOUS JOURNALISM. CONTRIBUTE TODAY.

Peltier, 80, Turtle Mountain Band of Chippewa Indians, left in an SUV and did not stop to speak to nearly two dozen supporters gathered outside the prison gates, The Associated Press reported.

He was set to return to his tribal homelands in North Dakota, where a homecoming celebration and community feed were scheduled for Wednesday.

“Leonard Peltier is free!” Nick Tilsen, founder and chief executive at NDN Collective, said in the statement. “He never gave up fighting for his freedom so we never gave up fighting for him. Today our elder Leonard Peltier walks into the open arms of his people.”

Tilsen has called Peltier “the longest living Indigenous political prisoner in the history of the United States.”

Supporters of AIM activist Leonard Peltier await his release from of the Federal Correctional Complex Coleman in Sumterville, Florida, on Tuesday, Feb. 18, 2025. Shown are, from left, Mike McBride, Ray St. Clair, center, and Tracker Gina Marie Rangel Quinones. (AP Photo/Phelan M. Ebenhack)

In poor health and after years of fighting for his release, Peltier was finally granted clemency by then-President Joe Biden just minutes before Biden left office on Jan. 20. Biden’s order will allow Peltier to serve out the remainder of his sentence with home confinement on the reservation.

“This moment would not be happening without [then-Interior] Secretary Deb Haaland and President Biden responding to the calls for Peltier’s release that have echoed through generations of grassroots organizing,” said Holly Cook Macarro, who handles government affairs for NDN Collective. “Today is a testament to the many voices who fought tirelessly for Peltier’s freedom and justice.”

Peltier, who was an activist with the American Indian Movement during the 1975 standoff, has long maintained he was wrongfully convicted. He was convicted of murder in the deaths of FBI agents Jack Coler and Ronald Williams, but those convictions were overturned, leaving him with convictions for aiding and abetting in their deaths.

A woman who testified that she saw Peltier shoot the agents later recanted, saying she had been coerced into making the statements.

“He represents every person who’s been roughed up by a cop, profiled, had their children harassed at school,” said Nick Estes, a professor of American Indian Studies at the University of Minnesota and a member of the Lower Brule Sioux Tribe who advocated for Peltier’s release.

Supporters gathered outside the prison Tuesday, waving signs saying “Free Leonard Peltier.”

“We never thought he would get out,” said Ray St. Clair, a member of the White Earth Band of the Minnesota Chippewa Tribe who traveled to Florida to be there for Peltier’s release. “It shows you should never give up hope. We can take this repairing the damage that was done. This is a start.”

Not everyone cheered his release, however, Former FBI Director Christopher Wray, who resigned as the Donald Trump took office, called Peltier “a remorseless killer” in a private letter to Biden obtained by The Associated Press.

Peltier had long sought release from prison, and was most recently denied parole in July. He would not have been eligible again for consideration until 2026.

He thanked his supporters Tuesday in the written statement and looked ahead to the homecoming.

“Thank you to all my supporters throughout the world who fought for my freedom. I am finally going home. I look forward to seeing my friends, my family, and my community. It’s a good day today.”

This article contains material from The Associated Press.

Our stories are worth telling. Our stories are worth sharing. Our stories are worth your support. Contribute today to help ICT carry out its critical mission. Sign up for ICT’s free newsletter.

‘Losing our voice, losing our space’

Jourdan Bennett-Begaye and Kalle Benallie

ICT

WASHINGTON — The anger, resilience and ready-to-fight energy radiated from tribal college and university presidents and students as they packed into the conference room Tuesday, Feb. 4, for National Tribal College Week.

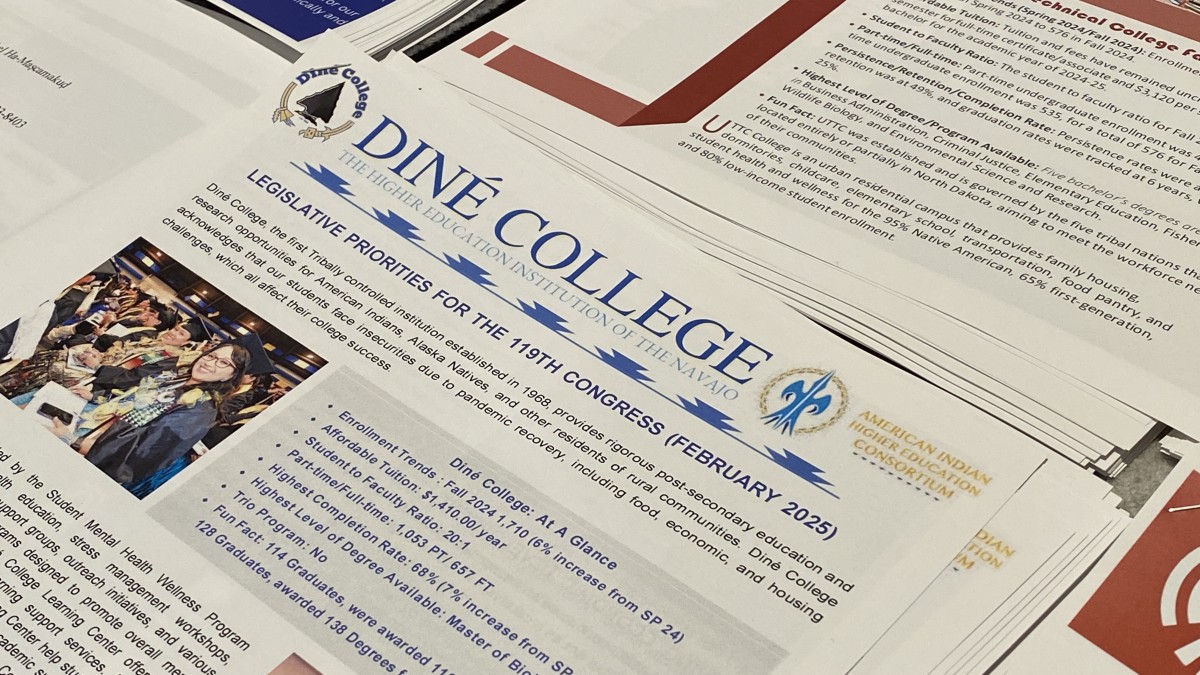

They arrived from as far away as Utqiaqvik, Alaska, for the annual tribal college and universities legislative summit hosted by the American Indian Higher Education Consortium, an organization that represents and supports all accredited tribal colleges and universities across the country. Of the 37 institutions in the country, 35 were represented at this year’s annual summit.

They already were bracing for what they would face in the coming year.

In just the first three weeks of his new administration, President Donald Trump had already signed an executive order on his first day in office that rescinded the White House Initiative for Advancing Educational Equity, Excellence, Economic Opportunity for Native Americans and Strengthening Tribal Colleges and Universities. The initiative had promoted the success and growth of Indigenous education in public schools, at home, or schools operated or funded by the Bureau of Indian Education, Department of the Interior, or postsecondary educational institutions, including tribal colleges and universities.

A week later came news of an abrupt decision to freeze federal grants and loans, which could affect more than $1 billion of federal funding for tribal nations in education, healthcare, climate initiatives, law enforcement, agriculture, and more.

Several lawsuits were filed immediately, and judges have placed a temporary block on the federal funding freeze, but administration officials indicated that “some kind of funding freeze is still planned as part of his blitz of executive orders,” The Associated Press reported.

A screenshot of the White House initiative floated around Native peoples’ and allies’ social media feeds of the action with comments expressing how upset they were with Trump’s order.

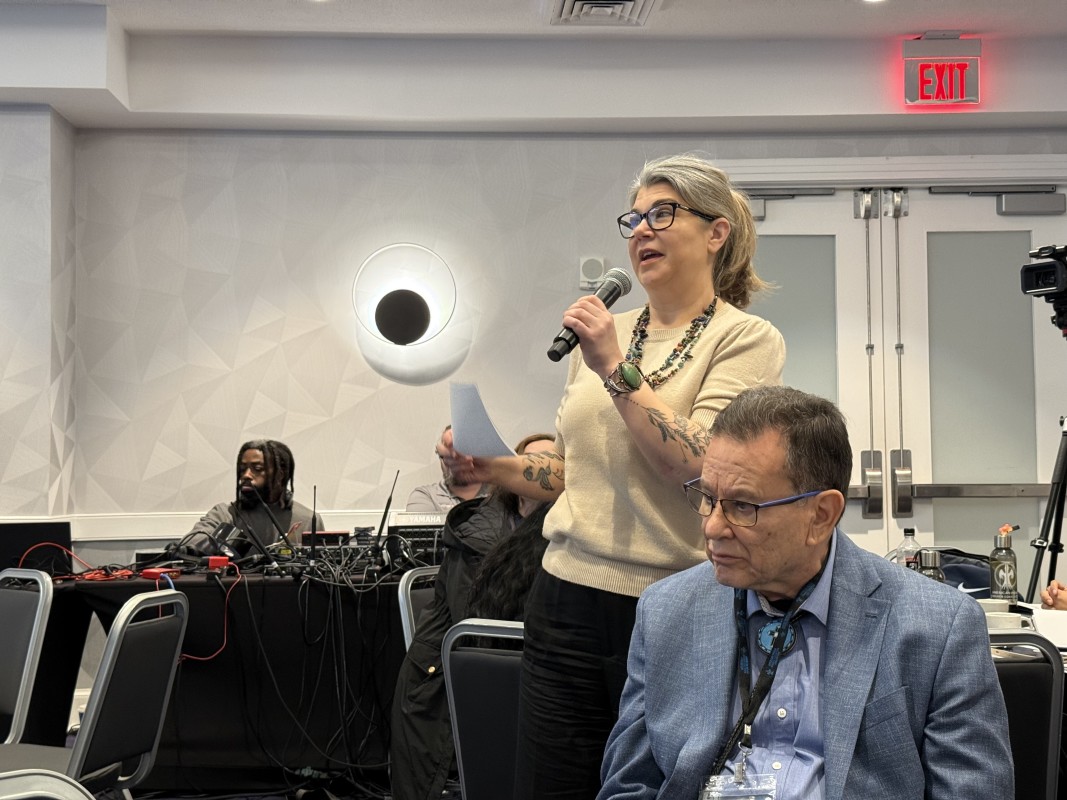

The consortium’s president and chief executive, Ahniwake Rose, a citizen of the Cherokee Nation and of Muscogee (Creek) descent, stood on the stage encouraging college presidents and students to share their stories with their representatives and explain how the decisions will impact their education, institutions, families, communities, and tribal nations.

She said even a “pause” in funding would affect them.

“That’s the important part —the pause in funding,” she told ICT. “Because while the freeze has been lifted, the pause might not be and while we’re settling and figuring out what the executive orders mean across the agencies, the real-life impact for our TCUs is going to be felt immediately.”

Austin Boots, left, is a first year student at Iḷisaġvik College in Utqiagvik, Alaska, who attended the 2025 American Indian Higher Education Consortium Legislative Summit on February 4, 2025 in Washington, D.C. (Jourdan Bennett-Begaye, ICT)

Ahniwake Rose, president and chief executive officer of the American Indian Higher Education Consortium, asked a question during the Farm Bill panel at the consortium’s annual legislative summit on February 4, 2025 in Washington, D.C. Rose is a citizen of the Cherokee Nation and of Muscogee (Creek) descent. (Jourdan Bennett-Begaye, ICT)

Facing a potential funding freeze

Rose, who previously served as the consortium’s vice president of congressional and federal relations, told ICT that when the organization found out about the funding freeze, officials immediately sent a survey to all the tribal colleges and universities asking how the move would affect the day-to-day operations and impact the institutions and their students.

Tribal colleges and universities receive 74 percent of their total revenue from federal funding. If the freeze continues, tribal colleges and universities could shut down, according to the impact sheets from the surveys that congressional leaders will receive this week.

More than 30,000 jobs are created across the local and regional economies. Most of these jobs are tied to federal funds and would affect faculty and staff positions, on and off campus.

Rose said many of the larger state institutions have alumni and endowments to draw from, but that doesn’t apply to all 37 tribal colleges and universities. Some of the TCUs don’t have six months of reserves, either.

“So a pause in funding that lasts six months means that we’re losing faculty,” she said. “A pause in funding for six months means that we’re closing courses. And if we close a course, if we lose (a) classroom, we’re losing students, then we’re losing revenue from our student enrollment.”

She continued, “So the ripple effect will be long-lasting. If this is not just a freeze, if this is just a pause, if it goes on much longer, then it will have a devastating impact on our TCUs. Some of our TCUs have noticed that, or have noted that, if it goes past six months, they might have to consider closing.”

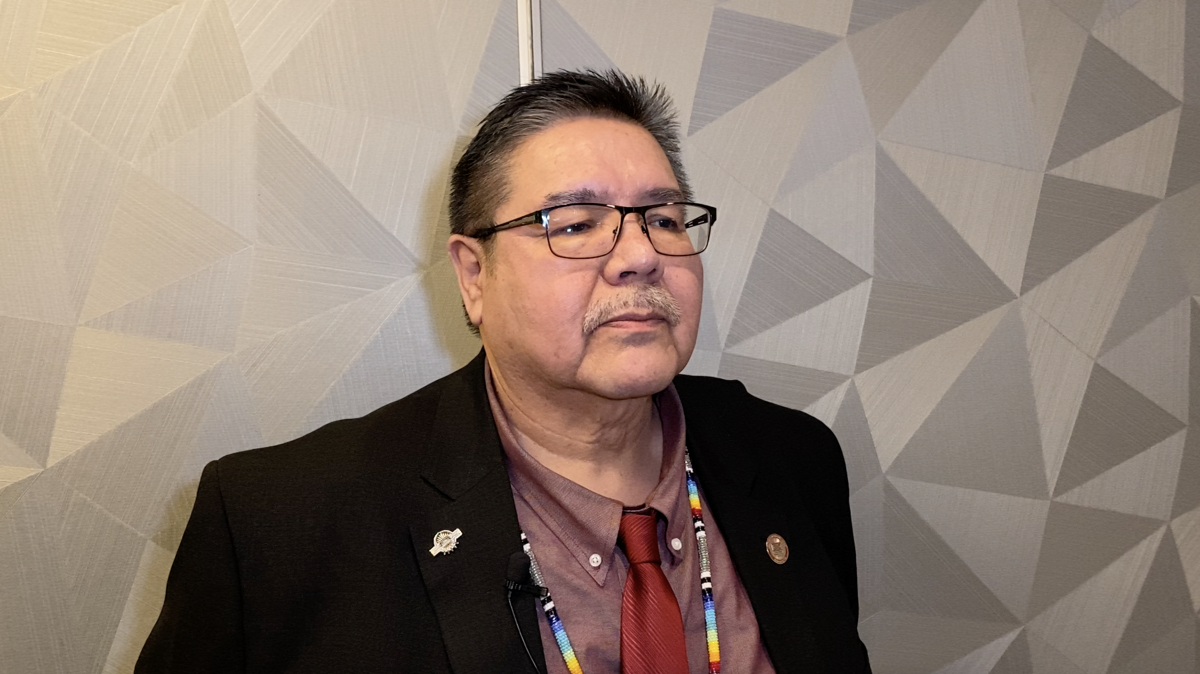

Leander R. McDonald, president of United Tribes Technical College in North Dakota, estimates that his college has six months of reserves. He is Ihanktowan, Sahnish, Hidatsa, and Hunkpapa, and serves on the consortium’s board as vice chair.

“After that we would have to discontinue operations,” he said. “So when we started hearing about these funding freezes, we started looking at our budgets a little bit more closely and saying … ‘Well, what do we need in order to get us to the end of the school year?’”

McDonald said about two-thirds of the college’s funding relies on federal funds, with one-third coming from endowment monies and foundations.

Each institution also has to worry about accreditation, officials said, since tribal colleges and universities are obligated to meet the standard for each area of study, he said. They have one of two choices: fulfill the educational commitment themselves or refer students to other educational institutions.

“We’re certainly in quite a predicament should that funding freeze happen, because we wouldn’t be able to complete the mission that we’re set out for,” he said. “We would need time in order to stop operations, and we’d be liable for that, and with the treaty and trust responsibility, just begs the question is that, do we file suit as a result of that, for the liability that we’re incurring as a result of a pullback of federal funds? And I think that’s where the majority of us as tribal colleges would fall in my mind.”

Twyla Baker said Nueta Hidatsa Sahnish College’s soft-funded projects are approximately 60 percent made up of federal funds. Soft-funded projects are grants, sponsored-programs, private donations, anything external to the tuition money they receive. Baker is the president of the North Dakota college and a citizen of the Three Affiliated Tribes.

The school has done a lot to build up its reserves and endowment but it’s nowhere near where they need it to be. It’s still in the “infancy” stages, she said.

“It’s not something that we would be able to tap into long term, and we haven’t even really tapped into it right now to start pulling the interest off of or anything like that, because we still wanted to build it up,” she said.

“We’ll probably be able to stay for the academic year if there are no pauses in federal funding. But beyond that, it starts to be a big question mark,” Baker said.

Closing the educational doors would have a “colossal impact” on her students, she said.

“We live in a very rural and remote area in Northwest North Dakota, and these students can easily drive up to an hour one way to come to school with us,” said Baker, who sits on the consortium board as the research chair.

“They receive all types of supports that we can possibly find for them, and a lot of them are tied to federal dollars, so it’s crucial that we are able to keep our relationship considered under treaty and trust, and that those dollars can continue to come to the tribal colleges, and that we be kept in that consideration,” she said.

The United Tribes Technical College and Nueta Hidatsa Sahnish College are two of five tribal colleges and universities in the state.

The consortium’s impact sheet from North Dakota, for example, offers a closer look at the impact a disruption in funding could cause. The impact sheet, summarized by the consortium, indicates the harm could be felt in five areas:

- Immediate impact: Reduced services, staff layoffs, tuition spikes, and campus program closures

- Financial consequences: Dependence on federal grants means institutional operations would be at serious risk. Tuition would increase drastically to offset loss of federal funding.

- Impact on students: Loss of educational opportunities for TCU students, increased dropout rates, financial insecurity, and loss of access to crucial financial aid.

- Impact on faculty/staff: Staff and faculty would face severe job losses, impacting institutional stability.

- Impact on research: Research activities would be disrupted, particularly those funded by federal agencies such as NASA and U.S. Department of Agriculture.

A Diné College information sheet at the 2025 American Indian Higher Education Consortium Legislative Summit on February 4, 2025, in Washington, D.C. (Jourdan Bennett-Begaye, ICT)

Extensions of sovereignty

Rose, McDonald, and Baker emphasized that tribal colleges and universities are chartered by federally recognized tribes, and are therefore extensions of tribal nations and sovereignty.

“We’ve ceded billions of acres of land to this country to and in exchange for that we have certain protections, and we have a relationship with the federal government that ensures that we have services in place,” Baker said. “We have education, health care … infrastructure, things in place to ensure the health and the well being of our peoples in perpetuity, because they bet they benefit from the land that was ceded.”

There’s also federal legislation in 1994 that designated more than a dozen tribal colleges and universities land-grant institutions. They are part of a land-grant university system that dates back to 1862. Most TCUs are now considered land-grant institutions.

The first tribal college was Diné College, known as Navajo Community College before 1997. Former Navajo Nation Chairman Raymond Nakai established the college as a step toward self-determination in 1968, which was 100 years after the Navajo Treaty of 1868.

While self-determination was part of the formula, McDonald said the tribal colleges were also created to address non-completion of tribal students at mainstream institutions. He’s seen its success. “We’re able to provide a higher education experience where they’re at home and they’re able to experience higher education and courses and programs of study that they receive and complete them (courses and programs) as a result of coming to school with us and at higher rates than they do with mainstream institutions,” he said.

Attendees at the annual American Indian Higher Education Consortium Legislative Summit in Washington, D.C., on February 4, 2025. (Jourdan Bennett-Begaye, ICT)

The annual American Indian Higher Education Consortium Legislative Summit took place in Washington, D.C., during the first full week of February 2025. (Jourdan Bennett-Begaye, ICT)

From associate degrees to doctorates

The number of tribal colleges and universities has grown since the start-ups decades ago.

According to the consortium numbers:

- Thirty-seven tribal colleges and universities operate at 90 sites in 16 states — Oklahoma, Kansas, Nebraska, Michigan Wisconsin, Minnesota, North Dakota, South Dakota, Montana, Washington, Idaho, Utah, Arizona, Alaska, California, and New Mexico

- TCUs serve 80 percent of Indian Country

- Approximately 160,000 Native students and community residents are served by TCUs

- 245-plus federally recognized tribes have students at these institutions.

Many of these schools offer degrees ranging from associate to doctoral degrees.

Perhaps the biggest misconception of tribal colleges and universities, however, is that they are for Native students only. Non-Native students, or non-enrolled, can also attend most TCUs. About 13 percent of the students enrolled at tribal colleges and universities are non-Native, according to the consortium.

For Baker’s college, that number hovers around 10 to 15 percent for their non-beneficionary, or non-Native, students.

“We are public institutions of higher education, so they can come to school with us and are held to the same standards as the rest of the other colleges, mainstream colleges in the state and in the country,” she said. “We are accredited by the same accrediting bodies, and they can get their education with us or get their start with us at a really good deal, because we are very cognizant of the students that we’ve worked with and their socioeconomic backgrounds. So we try to support them, and we understand how tough it can be for some of these students to access higher education if it weren’t for a TCU, and that includes non-enrolled students.”

McDonald and Baker both said that their alumni go on to work in their communities as entrepreneurs, scientists, artists, and more. They become part of the workforce and contribute to their families, communities, nations, and American society.

“I think it’s a great investment that needs to be continued by the U.S. government and recognizing our contributions here, not only for the cessation of land, but also our contributions too, for building this country,” McDonald said.

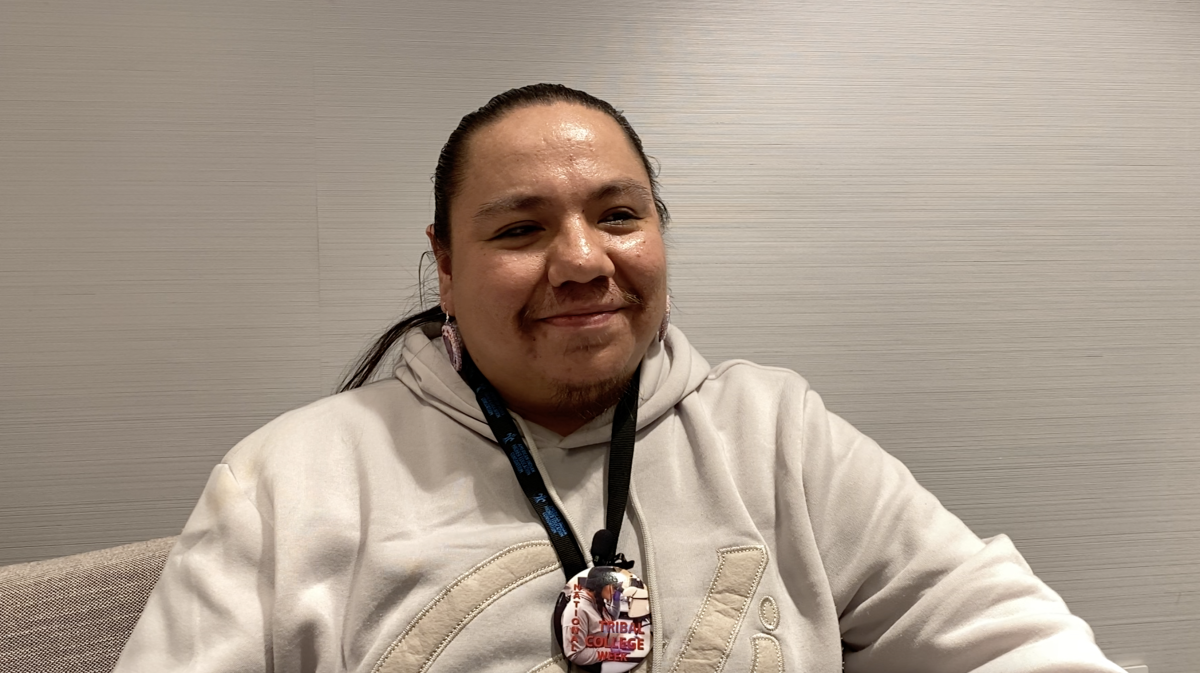

Leander R. McDonald is president of United Tribes Technical College in North Dakota. He is Ihanktowan, Sahnish, Hidatsa, and Hunkpapa. McDonald attended the 2025 American Indian Higher Education Consortium Legislative Summit in Washington, D.C. (Jourdan Bennett-Begaye, ICT)

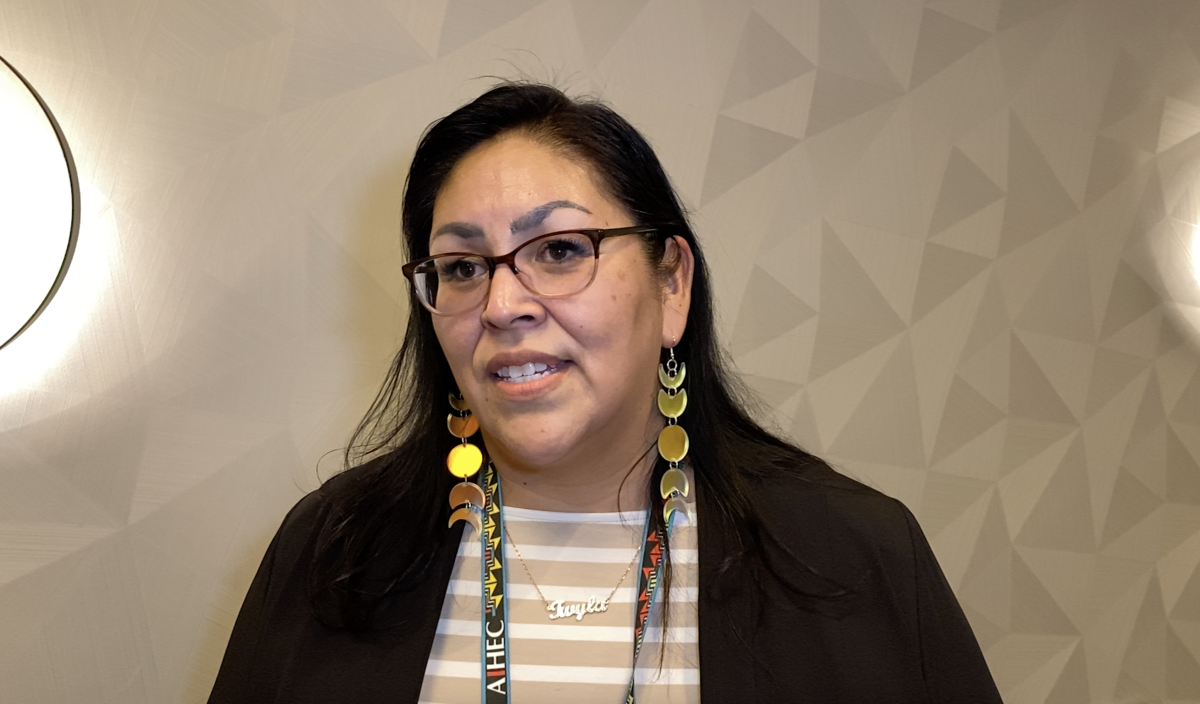

Twyla Baker is president of Nueta Hidatsa Sahnish College in North Dakota. She’s a citizen of the Three Affiliated Tribes and attended the 2025 American Indian Higher Education Consortium Legislative Summit in Washington, D.C. She serves as the consortium’s research chair. (Jourdan Bennett-Begaye, ICT)

Swept into DEI

Despite the broad impact tribal colleges and universities have had on their communities, Trump’s decision rescinding the White House initiative implemented under President Joe Biden startled much of Indian Country.

Tribal nations are not part of the anti-DEI (diversity, equity and inclusion) rhetoric because of political and legal obligations.

The executive order rescinded had “unwavering” support from both sides of the aisle, according to Rose. She hopes that the administration understands that tribal colleges and universities are nation builders that are connected to sovereignty.

The American Indian Higher Education Consortium, along with two dozen tribal organizations that represent tribal nations and communities, issued a letter to Trump on Feb. 2.

The coalition summarized in a statement, “Tribal Nations are not special interest groups—they are sovereign governments with a unique legal and political relationship with the United States and with their own Tribal communities. The trust and treaty obligations of the federal government are political and debt-based in nature. Tribal Nations’ sovereignty and the federal government’s delivery on its trust and treaty obligations must not become collateral damage in broader policy shifts.”

Trump’s executive order dissolved the initiative, which was housed in the Department of Education, and eliminated the executive director position.

“This was our political office, and so by losing the political appointee, we lose some direct access to the (education) secretary,” Rose said. “We lose the opportunity to directly impact policy, to have somebody that understands what it means to work at a tribal college and university, and to ensure that as policies and as regulations and as legislation is being implemented and put into place, that our students and our faculty and our communities are being specifically addressed and thought about.”

It was a surprise for the former executive director of the initiative, Naomi Miguel. She joined the initiative in February 2023.

“My shock was more or less on the fact that this was a day-one first executive order action,” said Miguel, T’ohono Odham citizen. “That was one of my first shocks. My second shock was the amount of work that we did in that initiative and knowing that work is not going to continue in this administration.”

She said the initiative also provided information to different agencies and outside stakeholders such as non-Native institutions that are specifically interested in recruiting Native students for their programs.

She added that during her work she made efforts to inform those in the federal workplace and non-Native organizations that the Native American and Alaska Native connection to education is political. Boarding schools were used as a tool to assimilate Indigenous children and federal funding is outlined in treaties.

“A lot of the work that I was doing was internally having those discussions. It was a lot of education about us and a lot of education on our status in this country that was fully backed by the Supreme Court for centuries. I think that type of work unfortunately isn’t going to continue,” Miguel said.

Native Hawaiians and Pacific Islanders will also be affected. Trump also rescinded the Executive Order 14031, Advancing Equity, Justice, and Opportunity for Asian Americans, Native Hawaiians, and Pacific Islanders.

Miguel said that she worked with the Department of Health and Human Services, which housed the initiative, repeatedly. They worked together with connecting Native Hawaiian education and helping develop the work they did, on the inter-agency level, with the Department of Interior for Native languages.

“Native Hawaiians and University of Hawai’i are kind of the road map for us in revitalizing and retaining our languages for Native languages,” Miguel said. “A lot of the work they were doing was starting to be connecting all of us together, really looking at a lot of our policy papers making sure we’re being inclusive of Native Hawaiians and Pacific Islanders.”

Miguel said that rescinding the initiatives will make it harder and slower for information to be easily shared about training and technical assistance, federal aid assistance, announcements from the Department of Education or general announcements about education.

“Our students will see the impact of that unfortunately,” Miguel said. “There were times when we had FAFSA grants available for schools to utilize to help their students fill out their FAFSAs or learn how to fill out their FAFSAs. That didn’t just apply to TCUs, it applied to other high schools that may have had high populations of Native students there. There are things like that that came up that is not explicitly named in that executive order.”

Miguel also encouraged the career staff who are still working in the Department of Education and other departments to take care of themselves from possible pushback from the Trump administration.

“We did a lot of work, and it is sad and it does break my heart a little to know that it’s gone, but we need each other,” she said.

Dakota Waupoose is a student at the College of Menominee Nation. This year, 2025, was his second time attending the annual American Indian Higher Education Consortium Legislative Summit in Washington, D.C. Waupoose is a Prairie Band Potawatomi citizen and is on the consortium’s Student Congress. (Jourdan Bennett-Begaye, ICT)

Stirring students to action

Executive orders are not in the U.S. Constitution but are accepted as part of a president’s executive powers to either amend, repeal or replace any previous executive order. Although Congress can’t easily overturn executive orders, federal courts can review, challenge or block the orders if they violate or contradict the Constitution, federal laws or fundamental rights.

That’s exactly what Dakota Waupoose is learning at the legislative summit. Waupoose is a student at the College of Menominee Nation. He will be advocating for TCUs on Capitol Hill all week.

“It’s just helping bring this information back from this legislative summit to our communities, so that they don’t have to worry as much, and understanding that when we come here, we’re representing them here on the Hill,” said the Prairie Band Potawatomi citizen who is part of the consortium’s Student Congress.

View the original article to see embedded media.

Our stories are worth telling. Our stories are worth sharing. Our stories are worth your support. Contribute $5 or $10 today to help ICT carry out its critical mission. Sign up for ICT’s free newsletter.

Interior Secretary nominee questioned about stance on Native issues

Daniel Herrera Carbajal

ICT

In his confirmation hearing Thursday before the Senate Committee on Energy and Natural Resources, President-elect Donald Trump’s nominee for Secretary of the Department of the Interior, former North Dakota Gov. Doug Burgum, responded to questions related to Native issues such as sovereignty and the epidemic of missing murdered Indigenous women.

If confirmed, Burgum will head a department that manages a half-billion acres of public lands, federal wildlife programs, and national parks and monuments. Burgum also would oversee many tribal functions, particularly the Bureau of Indian Affairs and Bureau of Indian Education.

He would replace Laguna Pueblo leader Deb Haaland, the first Native American to hold the position.

If confirmed, Burgum also would chair a new energy council charged with promoting oil and gas development. The council could play a key role in Trump’s effort to sell more oil and other energy sources to allies in Europe and around the globe.

During Thursday’s hearing, Washington Sen. Maria Cantwell (D) asked Burgum if he believed in tribal sovereignty and consultation.

“Tribal consultation to me as governor of North Dakota is spending time going to tribes, listening, sometimes listening for hours to really understand what the issues are,” Burgum said. “Working on things that are important.”

Burgum is an ultra-wealthy software industry entrepreneur who was born and raised in small-town North Dakota. He first took office as governor of the oil-rich state in 2016 and won re-election four years later. He endorsed Trump after ending his own 2024 presidential bid.

As the former governor of a state with five tribes, Burgum has a long history addressing Native issues. Not long after he took office, protests broke out near Cannon Ball, N.D., over the Keystone XL and Dakota Access pipelines. Fearing escalation, Burgum ordered all protesters leave the encampments by Feb. 22, 2017, saying he did not want protesters to be removed by force.

Burgum’s response to the protests raised alarms for tribes, and he and the Standing Rock Sioux Tribe continue to have opposing stances on the pipeline, but the two maintain a solid relationship and meet regularly. He is considered to have good relationships with other tribes in North Dakota as well and is credited with significantly improving dialogue between the state and its tribes.

Montana Sen. Steve Daines (R) emphasized Burgum’s reputation by presenting to the committee a letter from the Coalition of Large Tribes praising Burgum.

“It’s been incredible for COLT tribes to have such a close supporter nominated to the secretary’s office,” said Daines. “He was someone in whom we have deep trust and confidence.”

COLT is composed of more than 15 tribal nations, including the Navajo Nation, Blackfeet Nation and the Oglala Sioux Tribe.

Arizona Sen. Ruben Gallego (D) brought up the issue of missing and murdered Indigenous women, attributing the problem to a lack of tribal law enforcement.

Burgum agreed.

“One of the great tragedies is the lack of law enforcement on tribal lands, and the fact that we got organized crime preying on those gaps,” he said. “This is an unseen tragedy in America. The FBI list is now over 6,000 unsolved cases.

“We lost a college kid during spring break. It’s a Netflix series and the whole nation knows their name personally,” he said. “But we have the same individual tragedies happening over and over again in Indian Country and people aren’t even aware that it’s going on. We have to change our entire approach to this.”

Burgum talks about MMIW in clip below (2:16-4:23)

Trump’s ‘energy czar’

As Trump has dubbed Burgum his “energy czar,” he will be responsible for carrying out the President-elect’s plan of increased oil production. “Drill, baby, drill,” Trump has said.

“President Trump’s Energy Dominance vision will end wars abroad and make life more affordable for every family by driving down inflation,” said Burgum in his opening remarks. “President Trump will achieve these goals while championing clean air, clean water and our beautiful land.”

Hawaii Sen. Mazie Hirono (D) pushed back on this statement citing military leaders acknowledging climate change is a major issue.

“Were you aware that they testified before the Senate Armed Forces Committee a number of times that burning more fossil fuels is actually going to, in fact, not result in the end of wars but could very well exacerbate and cause wars?” Hirono said.

“Within fossil fuels, the concern has been about emissions, and within emissions we have the technology to do things like carbon capture to eliminate harmful emissions,” Burgum said.

Burgum attributed the need for more fossil fuel-powered electricity to America’s race with other global superpowers like China to develop powerful artificial intelligence technology that can have scientific, economic and military applications.

“We have a shortage of electricity and especially we have a shortage of baseload,” he said.

Baseload power is the minimum amount of electricity required over a period of time, and is generated by power plants that run continuously. Baseload power plants are a key part of an efficient electric grid.

“We know we have the technology to deliver clean coal,” Burgum said. “We’re doing that in North Dakota. This is critical to our national security. Without baseload we’re going to lose the AI arms race to China. And if we lose to China that has a direct impact on our national security.

“We need electricity for manufacturing and AI is manufacturing intelligence, and if we don’t manufacture more intelligence than our adversaries, it affects every job, every company, every industry,” Burgum said.

Utah Republican Sen. Mike Lee, chair of the Senate Committee on Energy and Natural Resources, questioned Burgum about the expansion of national monuments, including Bears Ears and Grand Staircase-Escalante in his home state, under the Antiquities Act.

The monuments – considered sacred to several tribes – were created over the objections of state officials. Burgum appeared to sympathize with Lee’s concerns. The nominee said the original intent of the 1906 law was for “Indiana Jones-type archaeological protections” of objects within the smallest possible area.

Burgum later touted the many potential uses for public lands, including recreation, logging and oil and gas production that can boost local economies.

“Not every acre of federal land is a national park or a wilderness area. Some of those areas we have to absolutely protect for their precious stuff, but the rest of it – this is America’s balance sheet,” he said.

What’s next

Former North Dakota Gov. Doug Burgum, President-elect Donald Trump’s choice to lead the the Interior Department as Secretary of the Interior, arrives to testify before the Senate Energy and Natural Resources Committee on Capitol Hill in Washington, Thursday, Jan. 16, 2025. (AP Photo/Jose Luis Magana)

Once the Committee on Energy and Natural Resources finishes its questioning of Burgum, it will send his nomination to the full Senate for a vote, either with its recommendation of Burgum or without it.

The Senate will then debate the nomination and vote on it, though no date for that debate has been set.

The Associated Press contributed to this report.

Our stories are worth telling. Our stories are worth sharing. Our stories are worth your support. Contribute $5 or $10 today to help ICT carry out its critical mission. Sign up for ICT’s free newsletter.