Back from the Dead: Shasta County Fountain Wind Project Could Be Approved Under New California Bill Designed To Fast Track Renewable Energy

In October 2021, Shasta County supervisors voted 4–1 against providing a permit for the Fountain Wind project, denying Houston-based corporation ConnectGen the right to erect forty-eight massive turbines up to 610 feet tall throughout the mountain ridges of Eastern Shasta County.

For the Pit River Tribe and a diverse coalition of Intermountain residents who mounted a strong resistance to the project, it was a stunning and momentous victory, the culmination of years of arduous organizing and researching. For ConnectGen, it represented the frustrating defeat of a project they argued was critical to reduce the impacts of climate change, which has already contributed to catastrophic fires and droughts throughout the state.

But the community coalition’s victory against the project, which some activists compared to David slaying Goliath in the Old Testament, proved to be short lived. This February, ConnectGen was able to file yet another Fountain Wind application, this time under a recently passed state law designed to ramp up the construction of new renewable energy sources.

State officials say that ConnecGen still needs to submit more required documents about the project before the new “opt-in” licensing process can begin. But assuming ConnectGen completes their application, Shasta County won’t have the power to veto the project the third time around.

That’s because under the recently passed AB 205, the Fountain Wind project won’t be evaluated by the county, but by state officials at the California Energy Commission (CEC), who have the power to override the county’s previous decisions. Fountain Wind is eligible for the AB 205 process because it would generate more than 50 megawatts of power (ConnectGen states it would produce about 216 megawatts, enough to power 86,000 California homes).

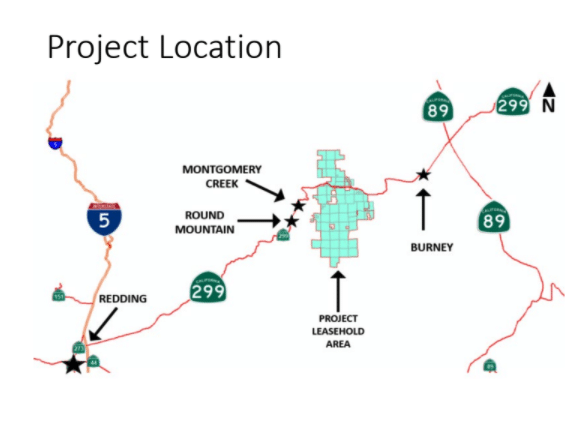

AB 205 also gives the state the authority to green light the project even if it breaks county law, as long as the CEC determines that the benefits outweigh the costs. That means ConnectGen could still build Fountain Wind even though the county has enacted a ban against giant wind turbines in the proposed project area, located about six miles west of Burney and just south of State Route 299.

Shasta County supervisors passed the new zoning amendment banning large-scale wind turbines in the unincorporated areas of Shasta County in December. It’s similar to measures other counties have implemented to restrict certain types of renewable energy development.

A significant reason Shasta County officials passed the ban was the testimonies from pilots and community researchers who argued that massive turbines impede aerial firefighting and can increase the threat of catastrophic wildfires to local communities.

Although ConnectGen’s new application for Fountain Wind is still incomplete, the studies they’ve submitted to the state so far suggest the latest version of the project would be about half the size of ConnectGen’s first proposal in Shasta County. In July 2021, Shasta County rejected that original project, which would have erected seventy-two turbines on 4,500 acres of leased land belonging to Shasta Cascade Timberlands, LLC in Eastern Shasta County. Just one month later, the County also rejected Fountain Wind’s second, much smaller, application, for a 48-turbine wind farm, similar to the size of the project now being proposed at the state level.

Shasta County rejected the two ConnectGen proposals only after many months of public meetings and environmental review. It was soundly opposed by the Pit River Tribe, who condemned the project because it would irrevocably damage sacred mountain ridges where the Tribe hold ceremonies, fasts, and gather plants for medicines and basketmaking.

In addition to expressing fears about increased fire risk, other Shasta County residents also told the County that building the turbines would imperil the natural springs they use for water. Many also expressed frustration that the North State’s natural resources already produce significant renewable energy that, like Fountain Wind, benefit corporations and other regions rather than locals.

Joseph Osa, a Montgomery Creek resident, was an organizer for the Stop Fountain Wind coalition. Speaking to Shasta Scout for this story, Osa said that he feels “disheartened” that the project has been resurrected by ConnectGen and could be constructed in Shasta County despite past denials.

In Shasta County, where concerns about disenfranchisement have contributed to dangerous public outrage and dysfunctional government meetings, Osa said the County’s previous decision to deny the Fountain Wind permit provided a rare and encouraging example of Shasta County government officials listening and responding to rural residents.

“If you attended those planning commission meetings, you saw (the officials) expressed concerns, asked questions based on their professional expertise and their knowledge of the local area. They really understood how this was going to impact us because they live here,” Osa said. “The (state isn’t) going to have those insights.”

Fountain Wind will be the very first energy project to be evaluated by the State under the new AB 205 process, making it a significant litmus test for how the CEC will flex its new muscle to authorize renewable energy infrastructure.

The law that gave the CEC its new powers to approve Fountain Wind emerged from growing tension between California’s drive to meet climate-friendly renewable energy goals and the often more locally-focused environmental, cultural and social priorities of the state’s small communities. Fountain Wind is one of several high-profile recent examples of communities rejecting or resisting large-scale renewable energy projects, including Humboldt County’s denial of the Terra-Gen wind farm in 2019.

California is likely to support a mega-project like Fountain Wind because it’s designed to alleviate the increasingly dire impacts of fossil fuel emissions on the world’s climate. Despite that, Tribes and local communities often resist them because their massive footprint can also cause damage to the local environment, endangered species, Tribal cultural sites, and property values.

Governor Gavin Newsom pushed for the passage of AB 205 in June in order to “streamline” the construction of green energy projects despite objections that it would usurp local decision-making power. According to the report, Newsom anticipates the bill will not only help California reach its clean energy goals, but also prevent the state’s recurring summer blackouts.

Newsom is not the first to focus on this issue. In 2018 Governor Jerry Brown signed SB 100 into law, committing California to generating 100 percent of its energy from renewable sources by 2045. “California is committed to doing whatever is necessary to meet the existential threat of climate change,” Brown said at the time.

While there is scientific consensus that it’s essential the world eliminate its reliance on fossil fuels, how to go about implementing that transition is a source of debate, especially since California’s energy appetite continues to grow. To reach its clean energy goals while satiating the state’s power hunger, one state analysis concluded that California will need to produce 6,000 megawatts of new renewable energy annually for several years, which would mean building the equivalent of 30 Fountain Wind projects each year.

While ConnectGen has not yet completed their state application, the CEC has already reached out to County officials for input about the plan, Paul Hellman, Director of the County Department of Resource Management, told Shasta Scout by email May 26. The County’s full response to the State is pending, Hellman said, but County officials have already told the CEC that they believe it would be “not appropriate” for the State to approve Fountain Wind under AB 205 for a variety of reasons, including the past rejections by local decision-makers.

He also noted that the ban against large wind turbines was a targeted regulation, and the county is interested in other proposals for renewable energy developments that are a fit for the unincorporated areas. Several small- and large-scale green energy facilities have been developed in Shasta County in recent years, he added.

If CEC approves the Fountain Wind energy project, it would contradict a local decision that was based on years of legally required environmental studies, public meetings, and consultations with the Pit River Tribe. Radley Davis, a Pit River Tribal Citizen who was also part of the coalition that opposed Fountain Wind, said the CEC shouldn’t even consider the Fountain Wind project because it was denied after such an extensive review.

Although he doesn’t speak for the Tribe’s government, Davis said he helped interview elders, review old ethnographic reports, and gather evidence of how the project would harm the Pit River people’s spiritual and cultural ways of life. Many other local residents with technical expertise also submitted extensively researched comments pointing out potential flaws with the project, Davis said.

“It’s like literally a do-over. It just doesn’t make any sense,” Davis said of the new application. “It’s incredible that the state can exercise such power; they don’t need permission from the Tribe or the County.”

CEC officials state they are closely examining the environmental studies and comments from the County’s review of the wind energy project. Because they’re aware of Pit River people’s concerns about the cultural impacts of the project, the agency has already begun consultations with the Tribe, far earlier than is required, wrote Louey, the CEC spokesperson.

Under AB 205, the CEC will conduct an entirely independent project review and then make a decision whether to license the project within 270 days, a timeframe that is relatively short considering the massive scale of the project. If ConnectGen completes their application, there will be some opportunities for public comments, according to Louey. These will include, at a minimum, a public meeting within thirty days of the application being accepted and a public meeting upon the release of the agency’s environmental impact statement on the project.

Ally Copple, a public relations consultant for ConnectGen, declined to respond to questions for this story, saying only that the corporation would not have any updates about Fountain Wind or comments about the AB 205 process until the public comment process begins. Copple did not respond to a follow-up question regarding whether ConnectGen intended to complete its application and when that might occur.

In 2021, ConnectGen officials were adamant that the County had made the wrong decision in denying the project. They told Shasta Scout while providing comments for previous stories that studies conducted during the environmental review indicated the project wouldn’t increase fire danger.

ConnectGen officials also argued that they modified the project significantly in response to community input and that the negative impacts of the Fountain Wind project are dwarfed by the dire need to transition away from fossil fuels and slow down climate change.

Despite the well-established need to transition from fossil fuels to cleaner energy, the CEC would have to provide significant justification in order to overturn the County’s previous decision on Fountain Wind, according to Hellman. The State would have to conclude that the Fountain Wind project would provide an overall positive economic benefit to the County, although it’s not clear what metrics they would use to do so. The CEC would also have to confirm that ConnectGen has cooperatively entered into legal agreements to provide benefits to community-based organizations or local Tribes.

In 2021, ConnectGen pledged to invest around $2 million into the local community impacted by Fountain Wind, including a $250,000 allocation for a Pit River Tribe jobs programs and $1 million for Round Mountain and Montgomery Creek community programs. However, the Pit River Tribe and several community members rejected the offer, stating the proposed benefits were paltry considering the potential damage and risk the $300 million Fountain Wind project could pose to the area.

Many also expressed frustration that ConnectGen’s engagement with the community seemed, in their eyes, like an attempt to pacify resistance rather than to truly work together to integrate renewable energy safely and respectfully into the area.

These perceptions of unfairness and disenfranchisement are common among local residents who resist or stop the construction of large renewable energy infrastructure in their communities, according to recent research. Scholars who have examined numerous case studies similar to Shasta County’s rejection of Fountain Wind contend communities may support renewable energy in general, but resist local projects because they aren’t designed with community knowledge, ways of life, or hopes for the future in mind.

These scholars suggest the development of renewable energy sources is not just a technological endeavor, but also a challenge to build new kinds of collaborative relationships among investors and state and local communities. One study recommends weaving community input and decision-making into the earliest stages of conception and design, working with residents to build renewable energy projects that fit their communities’ needs and landscapes.

It’s a new way of planning and development that appeals to Joseph Osa, the Montgomery Creek resident who helped organize the resistance to Fountain Wind.

“The energy projects should fit the local environment,” Osa said. “The state could help the counties zone areas for different types of energy projects to where they’re suited and encourage that development. Then the (environmental review) process might go much faster.”

Want to learn more? See the rest of our Fountain Wind coverage, here.

If you have a correction to this story you can submit it here. Have information to share? Email us: editor@shastascout.org