Lanai Ferry Seeks Higher Ticket Fare For The First Time In 15 Years

The public can weigh in next month on whether state regulators should approve the proposed 37% increase.

The public can weigh in next month on whether state regulators should approve the proposed 37% increase.

The community college system is falling short of one of its most important benchmarks: the number of students who transfer to a four-year college or university. It remains well below the system’s own goal, and lawmakers have taken notice.

“Although most students intend to transfer to a four-year university, few do,” wrote a group of state legislators this year as they asked the state to audit community college performance.

Set in 2017, the goal was to increase the annual number of community college students who transfer to the University of California and California State University from nearly 89,000 to more than 120,000 by 2022. In the 2020-21 academic year, the most recent data available, nearly 99,000 community college students transferred to a UC or Cal State.

The Community College Chancellor’s Office responded to questions regarding the transfer goal by forwarding a letter that former interim Chancellor Daisy Gonzales wrote to legislators in March as part of an internal negotiation regarding the audit. In it, she wrote that the goal “has not been fully achieved.”

She wrote that the UC and Cal State system rejected nearly 30,000 eligible community college applicants in fall 2020 — more than enough transfers to meet the community colleges system’s goal. She wrote there was “insufficient capacity” at the UC and Cal State campuses and asked the auditors to include equal scrutiny of those systems, since everyone is mutually responsible for coordinating successful transfers.

However, there are many ways to measure transfer. To get a clearer picture, CalMatters looked beyond the chancellor’s office goal and analyzed the raw number of students who transferred every year, which includes but is not limited to those who transfer to a UC or Cal State. Those numbers are reported by four-year institutions across the country and analyzed by the California Community College Chancellor’s Office. Undocumented students are not counted because they lack a Social Security number. It’s the methodology that most closely aligns with the state’s funding formula, which pegs the transfer numbers to the amount of money a college receives.

CalMatters then compared those numbers to the total number of students who, upon starting community college, said they eventually wanted to get an associate degree or transfer.

Of the students enrolled in a community college in California who said they wanted to transfer to a four-year university, an average of 9.9% went on to enroll at a four-year institution in 2021, the most recent data available.

There are many reasons why students never transfer. The state’s roughly 1.8 million community college students are predominantly low-income, first-generation students of color. Many students, especially older students, must juggle work, children, and for some, even homelessness while attending school.

But certain populations and colleges have a harder time with transfer than others. CalMatters found:

Lassen College has one of the lowest transfer rates in the state — 4.5% in 2021. It’s more than 10 percentage points below the highest performer, Irvine Valley College.

The reason is easy to see, said Roxanna Hayes, the vice president of student services at Lassen College in Susanville: The nearest four-year institution is over 80 miles away at the University of Nevada in Reno.

“It feels like we’re 2 hours from anything…when you come up to Susanville and you look around, there’s no other educational institution besides us.”

“We don’t have the sort of income that other counties have,” Hayes said. “It’s not just getting accepted to school: I’ve also got to live there and afford it.”

Among the community colleges with the lowest transfer rates, 60 percent are rural, and some are hours away from the nearest four-year institution.

Because of its proximity to numerous four-year institutions like UC Irvine and Cal State Fullerton, students at Irvine Valley College come to school already familiar with their transfer options, and most students don’t have to move if they want to pursue a bachelor’s degree, said Loris Fagioli, the director of research at Irvine Valley College.

The rural-urban divide is part of the problem, but it can’t explain everything, said Darla Cooper, the executive director of the Research and Planning Group of the California Community Colleges, a separate nonprofit organization that is funded in part by the chancellor’s office. The income of the student body, the focus and “culture” of the school, and even the economics of the surrounding town or city impact the transfer rate at any community college.

In the 2014-15 academic year, Los Angeles community colleges had some of the lowest transfer rates in the state, but that’s because many of its students were coming to community college unprepared, said Maury Peal, the community college district’s associate vice chancellor for institutional effectiveness.

The colleges enrolled those students in remedial courses, which can take years to complete and can reduce the likelihood of graduation. Backed by research that shows remedial classes to be ineffective, a law passed in 2017 and another in 2022 asked colleges to start placing students directly in college-level courses. Pearl said these reforms, plus other efforts like special degrees that guarantee a transfer to a Cal State or UC, have led to an uptick in transfer rates across the L.A. colleges.

West Los Angeles College, for instance, had a 5.4% transfer rate in 2015, among the lowest in the state. But by 2021, it was up to 12.3%, well above the statewide average.

“The fact that it’s improved is something we’re proud of, but it’s still not where we want to get to,” said Jeff Archibald, vice president of academic affairs for West Los Angeles College.

Unlike four-year institutions, which are often singularly focused on bachelor’s degrees for young adults, community colleges offer a range of educational opportunities depending on the demographics in the surrounding towns or cities, which can make it hard to compare one community college to another.

Located in Blythe, a rural town near the Arizona border, Palo Verde College has consistently had the lowest transfer rate of any community college. In 2021, just 1.1% of Palo Verde College students who indicated they wanted to transfer succeeded in doing so — but roughly half of the college’s students are in prison. Other rural colleges with low transfer rates, including Lassen College and Feather River College, also enroll a high percentage of incarcerated students relative to other schools.

Rural areas also come with different job opportunities, especially compared to the state’s highly educated coastal cities, Cooper said.

“Do the jobs where you’re located require a bachelor’s degree?” she said. “Because if they don’t, you’re probably not going to have a lot of transfer.”

In dense urban areas like Los Angeles, students tend to take classes at multiple community colleges, creating a “swirl” in the data that can mask some long-term outcomes, Archibald said.

But disparities still persist, even within the same city. Los Angeles Pierce College and Los Angeles Valley College, which are located in the San Fernando Valley, consistently outperform other Los Angeles community colleges.

Pearl said Pierce and Valley College have developed a reputation for preparing students for four-year colleges or universities. He pointed to other Los Angeles community colleges, such as Los Angeles Trade-Technical College, which are geared towards career and technical training.

A 2008 Research and Planning Group report found that a “transfer-oriented culture” was a recurring reason why certain community colleges had higher-than-expected transfer rates. The report also said those colleges had close relationships with local high schools and four-year institutions, along with support services for students.

Although the report was done 15 years ago, the transfer rate patterns have persisted. Many of those schools profiled by the Research and Planning Group in 2008, such as Irvine Valley College, continue to outperform their peers today, according to the CalMatters analysis of recent data.

Community colleges in wealthy areas or those with high-performing high schools have higher transfer rates, too. “We know this with almost all educational outcomes, there is an economic or socio-economic driver behind it,” Faglioli said.

Pearl said Los Angeles Pierce and Valley colleges benefit from “high-performing” charter schools nearby, which can boost transfer rates if community college students start school better prepared.

To encourage colleges to meet the system’s goal of increasing transfers to a UC and Cal State, community college officials put forward a new formula that pegged a portion of a community college’s funding to its outcomes. One of those outcomes is the number of people who transfer to a four-year institution.

But Lizette Navarette, interim deputy chancellor of the community college system, said that community colleges with low transfer rates are not getting penalized.

That’s because the new funding formula also takes into account the percentage of low-income students who meet certain benchmarks for success and the number of students who complete career-oriented programs. Navarette said rural colleges and other schools with low transfer rates have the opportunity to make up any potential gaps in state funding.

Lassen College, for example, received nearly $3 million more dollars last year than it would have under the previous funding formula, despite having some of the lowest transfer rates in the system.

However, the greatest impact of low transfer rates is not on the community college but on the student, Cooper said.

“For most people of color, most people who are low-income, community college is their only way into higher ed,” she said. “Even if what they want to pursue requires a bachelor’s degree, not everyone can go straight to a university.”

Four-year colleges and universities are selective and can be expensive, she said. While some community college students can earn more with a certificate or an associate degree than those with a bachelor’s degree, she said those students are the exception, not the norm.

“Everybody wants to bring out Bill Gates,” Cooper said. “He didn’t graduate college….If you can be that, awesome, great, fantastic. But for most people, it’s beneficial for life.”

In the internal letter to the state auditors, former interim Chancellor Gonzales pointed to areas where the community college system has seen significant gains toward its 2017 goals. More students are completing their courses and gaining degrees, for instance.

In general, more students are transferring to a four-year college, according to the CalMatters analysis, which includes upticks in the number of students transferring to a UC or Cal State. But the progress remains less than third of the goal that the chancellor’s office set out to accomplish by 2022.

A spokesperson for the Community College Chancellor’s Office said the system will deliver a new transfer goal “in the coming weeks.”

Data reporter Jeremia Kimelman contributed to the reporting for this story.

Adam Echelman covers California’s community colleges in partnership with Open Campus, a nonprofit newsroom focused on higher education.

Kristin Atwood, the town clerk and treasurer in Barton, spent most of her waking hours last week subbing in as part of the town’s road crew.

This week, she’s leading the municipal outreach to affected residents, trying to persuade neighbors she’s known since childhood to accept help recovering from the worst flooding to hit this small Orleans County town in living memory.

As the only full-time town employee who’s not able to operate heavy machinery, Atwood took on the tasks of driving all the back roads to find washed-out sections and place orange cones around them, so that others could get to work fixing them, she said in an interview on Wednesday.

That’s why, when representatives from the Federal Emergency Management Agency arrived at her office without warning the previous Saturday morning to visit residences damaged in last week’s historic flooding, the homes she knew of to show them were those of people who had posted pictures on social media, she said.

“I only got a call when people were outside my door,” Atwood said. “I didn’t have time to organize a list.”

With new Vermont counties added to the major disaster declaration Friday morning, Atwood hopes the federal assessors will come back to Barton.

Going door to door on Monday and Tuesday, she’s found a lot for them to see — dozens of residences that were severely flooded in town, both on both the north and south side of Barton Village and in downtown Orleans Village.

In Barton, and other small towns across the state impacted by flooding, municipal officials and nonprofit groups are realizing that the people who may need the most help are often the least willing or able to reach out and request it. You have to talk to them, and even then they may not reveal the full extent of what they are facing. To know that, you have to visit and see for yourself.

In Glover, another Orleans County town, the new town administrator, Theresa Perron, coordinated with Glover Rescue volunteers and other townspeople late last week, trying to reach every affected household. At least 10 and likely “well over” suffered damage she called “extensive” to their living space, some of which she was able to show FEMA representatives.

In addition to the door-knocking, Atwood has asked the owner and clerks at the nearby C&C Supermarket to try to engage anyone buying large amounts of cleanup supplies, such as garbage bags and bleach, to find out where they live.

In Greensboro Bend — a village in the Orleans County town of Greensboro between Glover and Hardwick — Jen Thompson, who co-owns Smith’s Grocery with her husband, Brendan, is taking on that role.

The store is up and running, although it took on water in the basement. Thompson is coordinating with another small business owner in Stannard who is trying to visit and check on every home.

“A lot of people, particularly in these areas, do not have internet and social media,” Thompson said on Thursday. “I feel like the damage is out there and I feel like it is a lot more than we know. It’s just trying to figure out who they are.”

For town leaders and social service organizations, finding those most impacted by the flooding is only the first challenge. The second is getting them to agree to accept assistance from people outside of their immediate family and friends.

“People don’t like to ask for help. They think their issue is nothing compared to somebody else’s,” said Thompson.

Atwood echoed that sentiment. “Asking for help is hard, especially for a lot of Vermonters. It’s an independent group,” she said in an interview on Wednesday.

When she visited, people smiled and shrugged and told her, “We made out fine” and “What can you do?” when she asked them how they were doing, she said.

At that point, the people she spoke with hadn’t called 2-1-1, Vermont’s flood damage hotline, but they promised to do so once she explained that reporting damage could help their neighbors access federal funds.

“Many of these houses are just over that line of acceptable” for safely living in, Atwood said. “A lot of the folks are older people used to doing for themselves and they are plugging away.”

Over the course of those two days, she gave out four dehumidifiers and 22 industrial-strength fans — everything that had been delivered the previous week to the town hall by the Vermont National Guard.

She wasn’t sure on Wednesday morning how many would actually stop by the “Multi Agency Resource Center,” a gathering of state and regional resources that was going to be set up the following day beneath the town offices on Barton’s village square. If people heard about it, some would need to get a ride — many personal vehicles were damaged by flooding.

On Thursday afternoon, a modest but steady stream of visitors was passing through the MARC, as it’s called by Vermont Emergency Management, in the basement of the Barton Memorial Building, which was flanked by large vehicles showing the logos of the Salvation Army and Red Cross. The pop-up center is scheduled to remain until 5 p.m. Saturday.

Outside, most of the people were gathering to pick up cases of water and a bucket of cleaning supplies from the Salvation Army, and a hot meal of sauerkraut and kielbasa from the Red Cross. Nearby, staff from the Vermont Food Bank and Northeast Kingdom Community Action, or NEKCA, answered questions and distributed food boxes, diapers and flashlights.

The Vermont Department of Health also had a table there, with free water-testing kits available for those with household springs and wells, as well as informational flyers that outlined the risk and potential health impacts of mold growth and how to safely clean out your home following a flood.

But several people had also made it inside to consult with the state Agency of Human Services about the loss of items purchased through the Three Squares food assistance program, said regional field representative Chris Mitchell. Nearby staff from the Department of Labor said they also had assisted a few people with information about unemployment insurance.

Momentum seemed to be building throughout the day as people in and around Barton told each other about what was there, Mitchell said. He knows they need to do more than simply tell town officials and state representatives, and announce the pop-up center on social media.

“We’re hoping word of mouth works,” Mitchell said. “We’re trying to spread the word.”

NEKCA is also aware that personal outreach is essential, said Casey Winterson, the group’s director of economic and community services. That’s one reason the nonprofit purchased two mobile units of their own, so they could provide direct services outside their offices in Newport and St. Johnsbury.

On Wednesday, his staff were in Groton, where they made contact with one family with young children who were without shelter and no longer able to stay in a campground that had been closed due to flooding, he said.

Consistent engagement is needed to reach many of the residents of the Northeast Kingdom and other rural regions who need the most help to recover after the flooding, said town officials.

These are households headed by elderly or disabled people, and those that have taken in extended families impacted by substance abuse, many including young children. Many could use a hand in clearing out the water and cleaning up what was left behind.

There were a few homes in Glover where cleanup appeared to be challenging the residents’ resources, whether financially, physically or emotionally, said Perron, the town administrator. “Some were overwhelmed with how to do it and what to do, or can’t do it. Some people do not have the capacity to make that happen,” she said.

Atwood estimated that in Barton there are at least 15 homes in town where there still is a significant amount of basic cleanup work to do, removing water-damaged items and housing materials. But for some, she said, “the help that is being accepted is the help that just shows up.”

That was the primary reason David “Opie” Upson, the town manager in Hardwick, declined the state’s offer to put the regional pop-up resource center in Hardwick. After visiting 50 affected households himself earlier in the week, he did not see how the center could help the dozen that still had significant damage they are unable to address, let alone the roughly seven that are not salvageable, he said.

“These are folks that aren’t going to show up at a crisis center. These folks won’t go to a multi-agency anything,” he said. “We need to go to them.”

He had asked his contact at the Agency of Human Services to provide direct individual assistance to those households. “This is a major construction project for these families,” Upson said. Meanwhile, “where they live is not getting any drier.”

Across the Northeast Kingdom and the state, family, friends and neighbors are showing up to help each other and their local business community recover. But in every community, there are people who have lost connections to both formal and informal resources.

In Orleans County, like elsewhere, two relatively new nonprofit groups have stepped in to try to bridge the gap.

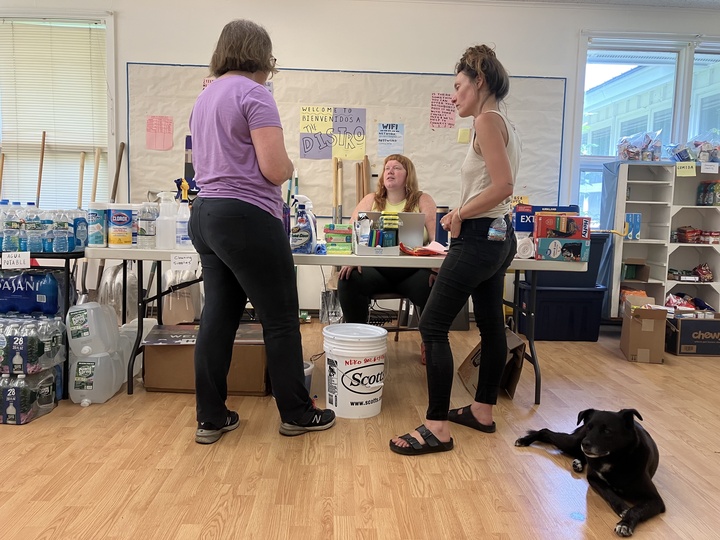

“The opioid epidemic has destroyed a lot of familial connections,” said Meghan Wayland on Monday afternoon while organizing donated food and cleaning supplies at the NEKO Depot, located in the back rooms of the Orleans Federated Church in Orleans Village. That’s where Northeast Kingdom Organizing set up its own resource center and communication hub within days of the flooding.

NEKO was born out of a collaboration among regional churches, the Caledonia Grange and the Center for Agricultural Economy in Hardwick, starting in 2017. The Orleans church was not one of the original organizations, but supporting the mutual aid group’s mission by opening up its space is an outgrowth of faith, said minister Alyssa May.

The group has been building relationships with people in the most affected communities for more than four years, said Ally Howell, who works for the agricultural nonprofit and is part of the NEKO leadership team.

“We were positioned really well to respond quickly in Barton and Glover and Orleans,” Howell said.

They began checking in with the families they knew as soon as roads were passable, and are trying to be in continuous touch and to understand their goals and needs, said Wayland, who is NEKO’s lead organizer and its primary eyes and ears on the ground.

“It may not look devastating. The pictures are not catastrophic,” they said on Thursday afternoon. “But we live in a region where people have already been on a tightrope. These people are living in low-lying areas and they have been clobbered by this thing.”

In Hardwick, the leaders of The Civic Standard, a nonprofit operating out of the former Hardwick Gazette building in the village, have been doing similar things. They mobilized volunteers to staff an emergency shelter that opened afternoon June 10, the first night of flooding there.

They also say the work is made possible by the presence The Civic Standard has been building in town for over a year. The group’s purpose, as described by co-founder Tara Reese, is simple but profound: “for people to be seen, to no longer be invisible to each other because of their differences,” she said.

A resource center, set up by The Civic Standard and the Hardwick Neighbor to Neighbor group, opened on the following Monday at the Hardwick Senior Center. By Wednesday morning, it had already given out all its dehumidifiers and more than 30 fans, and provided other kinds of support to 20 families, said volunteer Sarah Behrsing, who was staffing it then.

“It’s something we’ve been building on all the time anyway,” said co-founder Rose Friedman. The organization wasn’t founded to respond to a disaster, but it is able to fill that role because of connections it has made. Supporting a community is varied. “Sometimes that looks like disaster relief and sometimes it looks like trivia (night),” she said.

Other, older nonprofits are also playing a role. Thompson, the Greensboro Bend shopkeeper, said the Greensboro Association has provided funds for immediate assistance to local families. One family might need nights in a hotel; another one, help with material disposal.

“Going to the garbage is not cheap,” she said. “It’s definitely heartbreaking to see families who don’t have the means and resources.”

Having Wayland and other NEKO staff on the ground in affected communities has been invaluable in helping the state and regional groups understand community needs, said NEKCA’s Winterson. “They have been huge in that regard,” he said.

Mitchell said that, because of Wayland’s work, he is trying to coordinate deliveries to specific households by the Salvation Army’s van while it is in Barton.

NEKO is currently trying to bring materials and volunteers, while respecting residents’ wishes, to seven locations — and more are being added as they are found, Wayland said. The greatest need right now for the group are people in the trades and restoration professions who can help residents evaluate what is salvageable and what is not, they said.

“We need people who have done this before. We can’t order the dumpsters and leave people to coordinate the volunteers,” Wayland said. “We have a relationship; we don’t have the expertise.”

The Civic Standard group is working at three locations currently and matching volunteers at a few other locations, said Friedman on Thursday. It already has sufficient volunteers connected currently, and the work is not about ripping and tearing.

“People are still living in these houses and have a life in them and a lot of attachment to the things in them,” Reese said. At the Gazette building, they are also providing a quiet place where people can come to sit and talk.

Both NEKO and The Civic Standard know that they cannot solve every problem many of these households face. They can’t even make sure this doesn’t happen again.

“We can’t lift these houses out of a floodplain,” said Hardwick resident Helen Sherr, a summer fellow with The Civic Standard.

But people active in those organizations, as well as town officials, hope this long-term and difficult work —- which Friedman calls a “delicate dance” — will allow information and assistance to come more easily next time.

“I love these people. I grew up here. I want to help them look to the future,” Barton’s Atwood said. “I’m not naive enough to think this is the only time we are going to see this kind of water.”

Read the story on VTDigger here: In rural Vermont, reaching residents with flood damage takes a village.

IF CLAY BOLT WENT LOOKING for a rusty patched bumblebee, he would head to a city. The wildlife photographer said his best bet would be Minneapolis or Madison, Wisconsin, in a botanical garden or even someone’s backyard — as long as it was far away from crop fields and neonicotinoid pesticides.

“It’s kind of ironic. Cities have become a refuge for some of these most endangered pollinators,” said Bolt, manager of pollinator conservation for the World Wildlife Fund. “Thousands of acres of monocultural row crops leave little to no room for most pollinators.”

The rusty patched bumblebee has seen populations plummet with the rise of industrial agriculture and was given Endangered Species Act protections in 2017. The species, once broadly distributed throughout the eastern United States, is now largely found in small populations in parts of the Midwest.

Today, the bumblebee is among more than 200 endangered species whose existence is threatened by the nation’s most widely used insecticides (one classification of pesticides), according to a recent analysis by the U.S. Environmental Protection Agency. The endangered species range from Attwater’s greater prairie chicken to the Alabama cave shrimp, from the American burying beetle to the slackwater darter. And the star cactus and four-petal pawpaw are among the 160-plus at-risk plants.

The three neonicotinoids — thiamethoxam, clothianidin and imidacloprid — are applied as seed coatings on some 150 million acres of crops each year, including corn, soybeans and other major crops. Neonicotinoids are a group of neurotoxic insecticides similar to nicotine and used widely on farms and in urban landscapes. They are absorbed by plants and can be present in pollen and nectar, and have been blamed for killing bees or changing their behaviors.

Pesticide manufacturers say that studies support the safe use of these chemicals, which in addition to seed coatings, are also sprayed on more than 4 million acres of crops across the United States, including cotton, soybeans, grains, fruits, vegetables, and nuts. But conservation groups said that the EPA’s analysis has “gaping holes” and downplays the harm to endangered species.

“These are likely the most ecologically destructive pesticides we’ve seen since DDT,” said Dan Raichel, acting director of the Pollinator Initiative at the Natural Resources Defense Council, an environmental advocacy group that works to “safeguard the earth – its people, its plants and animals, and the natural systems on which all life depends.”

The chemicals “jeopardize the continued existence of” more than 1 in 10 endangered fish, insects, crustaceans, plants, and birds across the United States, according to the analysis by the environmental fate and effects division in the EPA’s Office of Pesticide Programs.

In 1972, the EPA banned DDT, an ecologically destructive insecticide that had gained widespread attention because of Rachel Carson’s book “Silent Spring,” which chronicled DDT’s role in harming the environment and driving species like the bald eagle toward extinction.

The EPA — which originally approved the three neonicotinoids in 1991, 1999 and 2003 — has been forced by a 2017 court settlement to assess the impact of the chemicals on endangered species.

The EPA has released the analysis with the hope of soon putting into place mitigations of the harm being caused, said Jan Matuszko, director of the environmental fates and effects division in the EPA’s Office of Pesticide Programs, in an interview with Investigate Midwest. An EPA spokeswoman said the EPA is planning to announce a proposed interim decision to re-register the neonicotinoids in September.

However, experts claim the way the agency analyzed the neonicotinoids’ predominant use — as seed coatings on crop seeds before they are planted — underestimates the amount the pesticides move off where it is applied and into species’ habitat.

Use of neonicotinoids skyrocketed in the late 2000s and has continued to rise, despite concerns about effects on pollinators and human health. In 2018, the European Union banned neonicotinoids because of concerns about harm to pollinators. On June 9, the New York state legislature passed a first-in-the-nation bill that would ban neonic-treated corn, soybean and wheat seeds; the bill is awaiting the governor’s signature.

In addition to environmental harm, scientists have expressed concerns about neonicotinoids’ effects on human health. In 2020, NRDC filed a petition asking the EPA to ban use of the chemicals on food because of risks to human health, including neurotoxicity and neurodevelopmental issues for children.

A 2022 study from researchers at 16 institutions across the United States found the chemicals in the urine of 95% of pregnant women in California, Georgia, Illinois, New Hampshire, and New York. A 2023 study by the U.S. Geological Survey found neonics in more than half of wells in eastern Iowa, as well as in the urine of 100% of farmers it tested.

“It’s way worse than what we’re able to pay attention to,” Bolt said.

The chemicals are manufactured by some of the largest agribusiness companies in the world. German chemical company BASF is the lead registrant on clothianidin; German multinational corporation Bayer is the lead registrant on imidacloprid; and Swiss company Syngenta, owned by ChemChina, is the lead registrant on thiamethoxam.

“It’s way worse than what we’re able to pay attention to.”

— Clay Bolt, manager of pollinator conservation for the World Wildlife Fund

Bayer spokeswoman Susan Luke said Bayer is committed to working with the EPA to “help ensure any new measures proposed by EPA are fully informed and based on sound science.”

“Bayer remains committed to the safe use of imidacloprid under label instructions; safe use that, along with other neonicotinoids, has been reconfirmed by regulators after diligent review worldwide,” Luke said in an emailed statement to Investigate Midwest.

Syngenta spokeswoman Kathy Eichlin said in an emailed statement that more than 1,600 studies have been conducted that support the safe use of thiamethoxam.

“Without neonics, growers would be forced to rely on a few older classes of chemistry that are less effective at targeting pests and require more frequent applications,” Eichlin said.

BASF spokesman Chip Shilling said in an emailed statement that clothianidin presents “minimal risk to humans and the environment including pollinators.” He said these products “undergo many years of extensive and stringent testing to ensure that there are minimal adverse effects to the environment, including threatened and endangered species, when used according to label directions.”

“We will continue to engage in extensive training and other stewardship activities to ensure that clothianidin seed treatment products are handled and applied safely,” Shilling said.

“THIS IS, AS FAR as we know, unprecedented. I’ve never seen a determination that was this large in scope,” NRDC’s Raichel said of the EPA’s analysis, adding, “EPA violated the Endangered Species Act when it approved these pesticides.”

Though the EPA was founded at the height of the environmental movement ignited by “Silent Spring,” the EPA has never assessed the impact of pesticides, which includes herbicides, insecticides, fungicides and rodenticides, on endangered species since the Endangered Species Act was signed into law by former President Richard Nixon in 1973.

However, the EPA has consistently lost Endangered Species Act lawsuits for decades. In April 2022, the Biden administration pledged to take action and released an Endangered Species Work Plan for pesticides.

Under the Endangered Species Act, the federal government cannot take any action that will “jeopardize the continued existence” of a protected species. In other words, the federal government cannot drive a species toward extinction.

If the government’s action is found to do so, it is called a “jeopardy” finding — which is rare. A 2015 review of seven years of consultations found only two jeopardy calls of more than 88,000 actions taken by the federal government during that time period. Jake Li, a co-author of that review prior to joining the EPA, is now deputy assistant administrator for pesticide programs at the EPA, overseeing the pesticide office.

Any federal agency that believes an action may harm an endangered species must consult with the U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service or National Marine Fisheries Service (depending on the species at risk) to see if that harm rises to the level of jeopardy — which means the species is less likely to survive because of the action.

In the case of these three neonicotinoids, the EPA released a biological evaluation in 2022 finding that these specific insecticides are likely to adversely affect — or harm — between 1,225 to 1,445 listed species, depending on the active ingredient. This is between two-thirds and three-fourths of all protected species in the U.S.

The U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service or National Marine Fisheries Service are then supposed to weigh whether that harm would rise to the level of extinction. In this instance, however, the EPA did its own analysis because the two agencies are backlogged in their analyses on pesticides, Matuszko said.

“This is, as far as we know, unprecedented. I’ve never seen a determination that was this large in scope. EPA violated the Endangered Species Act when it approved these pesticides.”

— Dan Raichel, manager of pollinator conservation for the World Wildlife FundDan Raichel

“It’s going to be awhile before (the services’ analyses) comes out,” Matuszko said. “The reason we’re doing this is to get mitigations in place for listed species much earlier. We want to be able to protect those species before we go through the entire consultation process.”

A spokeswoman for the U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service — which oversees implementation of the ESA for terrestrial species and freshwater species — declined to answer questions, instead referring questions to the EPA.

Genevieve O’Sullivan, a spokeswoman for CropLife America, said the trade organization that represents pesticide manufacturers appreciates EPA’s work on the analysis to get mitigations in place for protected species.

“The new report provides better data for industry and growers to work with the relevant federal agencies as they determine additional mitigations for the continued responsible use of pesticides,” O’Sullivan said in an emailed statement.

THE EPA’S ANALYSIS, THOUGH, found that the largest use of neonicotinoid insecticides — as seed coatings – will not cause species to go extinct. Researchers who study the environmental impacts of neonicotinoids say the EPA’s analysis downplays the risks.

Justin Housenger, a branch chief in the environmental fates and effects division of the EPA’s Office of Pesticide Programs, said in an interview that in the EPA’s analysis, they found seed treatments to be safer than other uses of the chemicals because seed treatments have “no offsite transport,” meaning they don’t run off into water or drift into the air.

However, it is “widely accepted” by researchers that seed treatments do move off of where they are applied, said Christian Krupke, a professor of entomology at Purdue University, who has published extensively about the environmental impacts of neonicotinoid seed treatments.

Research by Krupke and others shows that treated seeds lose up to 95% of the pesticide to the environment. This happens through seed abrasion and drift during the planting process or loss to soil or waterways through erosion. Birds can also eat treated seeds that are not properly buried.

“There is no doubt that there are important non-target effects (of seed treatments),” Krupke said.

Housenger said because the seeds are precision planted in fields, they likely don’t move off of where they are planted. He also said that the EPA’s analysis recognized “dust off” of pesticides during planting could happen, but doesn’t “quantitatively assess it further.”

Housenger added that seeds are physically too big for many endangered birds to eat. Further, the EPA’s analysis found that unless a species’ habitat was the treated agricultural field and its diet was primarily seeds, it would not face a jeopardy call, Housenger said.

“Unlike with foliar and soil applications, there’s no offsite transport,” Housenger said. “When you stack all these lines of evidence together, that’s why you’ve got this relatively low number, even though seed treatment considerations and uses were considered.”

The EPA’s assessment disregards well-established research in the field, said Maggie Douglas, assistant professor of environmental science at Dickinson College.

“I don’t know where that disconnect is coming from, but it does seem to exist,” Douglas said. “At this point, there’s quite a lot of evidence that this (movement) is happening. Seed treatments are not just staying in the field.”

In recent years, the U.S. Geological Survey has found neonics in rivers across the United States, tributaries to the Great Lakes, and well water and groundwater in Iowa.

“Treated seeds are no question in my mind why we’re finding this,” said Dana Kolpin, a research hydrologist with the U.S. Geological Survey, who has been an author on many of those studies.

A 2021 study by Kolpin and others found that clothianidin was in 68% of groundwater in northern Iowa and southern Minnesota. Clothianidin is used heavily as seed treatments in corn, but rarely used otherwise in those states.

That these chemicals are used on half of all cultivated cropland shows how widespread the pollution could be, said Bill Freese, science director at the nonprofit Center for Food Safety.

“It’s a huge issue. We’re talking the biggest crops in America,” Freese said. “Yet EPA is convinced these seed treatments don’t jeopardize species. I think that’s the most glaring evidence of how bad their assessments are.”

NO ONE KNOWS THE EXACT acreage planted with neonicotinoid treated seeds, but it is by far the largest-scale use of the chemicals, said Douglas, who has published extensively on tracking how, where and to what extent neonics are used.

As of 2012, about 150 million acres of crops were planted with neonicotinoid-treated seeds each year; the coatings are applied to the seed prior to planting. Neonicotinoids are considered systemic, which means that plants absorb the chemicals and spread them through their circulatory system. This makes flowers, leaves, nectar, and pollen harmful to both pests and non-target insects.

The neonicotinoids can often be taken up by non-target plants, including wildflowers and other native plants on the edges of fields. A paper by Krupke found that more than 42% of the land in Indiana is exposed to neonic pesticides during corn planting, impacting the habitat of more than 94% of the bees in the state.

“This is an avoidable problem. In most cases, it’s not helping crops, yields or farmers.”

— Christian Krupke, professor of entomology at Purdue University

The U.S. Geological Survey, which tracks overall pesticide use by purchasing data from a third-party contractor that gathers the information via farmer surveys, stopped tracking seed treatments in 2015 because the data was too complex and full of uncertainties, according to the USGS website. Many farmers also do not know which seed coatings they are planting, making accurate information difficult to get, Douglas said.

After the USGS stopped tracking seed treatments, recorded use of the chemicals — through applications by growers, such as spraying — fell significantly. Imidacloprid usage immediately dropped in half, while thiamethoxam use has dropped about seven-fold, and clothianidin usage has dropped more than 35-fold, USGS data shows.

Housenger said the EPA also does not know exactly how many acres currently are treated with neonic-coated seeds. An EPA spokeswoman, though, said the agency estimates that between 70% and 80% of all corn, soybean and cotton acres are planted with neonicotinoid-treated seeds. In 2023, that would range from 135.3 million to 154.64 million acres. This does not include treated seeds of other crops, including fruits and vegetables.

THE ENDANGERED SPECIES ACT is the sole way to mitigate environmental harm from treated seeds, because of a loophole in how these seeds are regulated.

The EPA regulates all pesticides through the Federal Insecticide, Fungicide and Rodenticide Act, or FIFRA. Using that standard, the EPA must weigh whether a pesticide causes “unreasonable adverse effects on the environment.” But unlike the Endangered Species Act, the EPA has the discretion under FIFRA to make a determination of whether environmental harms outweigh the benefits caused by the use of pesticides.

Seed coatings, however, aren’t regulated by FIFRA.

The EPA exempts seed coatings because of a loophole called the treated article exemption. Originally designed so the EPA didn’t have to evaluate the safety of lumber treated with chemicals for preservation, the EPA has since expanded that definition.

On May 31, the Center for Food Safety, a nonprofit that promotes environmentally safe and healthy food systems, filed a lawsuit against the EPA arguing that the agency cannot exempt coated seeds under FIFRA because they, unlike other “treated articles,” have widespread devastating impacts that EPA does not properly assess.

RELATED STORY: Bees, plants among the more than 200 species in jeopardy, due to neonicotinoid use

Krupke said there is little research that supports the effectiveness of seed coating to protect corn and soybeans under typical field growing conditions. A 2014 analysis by the EPA found that soybean neonicotinoid coatings “provide negligible overall benefits to soybean production in most situations.”

“We don’t need to be using nearly as much of these as we’re using,” Krupke said. “This is an avoidable problem. In most cases, it’s not helping crops, yields or farmers.”

The post Three widely used pesticides driving hundreds of endangered species toward extinction, according to EPA appeared first on Investigate Midwest.

NEWBERN, Ala. — There’s a power struggle in Newbern, Alabama, and the rural town’s first Black mayor is at war with the previous administration who he says locked him out of Town Hall. After years of racist harassment and intimidation, Patrick Braxton is fed up, and in a federal civil rights lawsuit he is accusing […]

The post A Black Man Was Elected Mayor in Rural Alabama, but the White Town Leaders Won’t Let Him Serve appeared first on Capital B.

Dozens of rural Fresno County residents spoke out Wednesday, urging California leaders to address the “urgent need for investment” in local broadband internet access.

“We want, and we need broadband of the highest quality,” said Martha Sanchez, a resident of Selma. “It’s not a luxury anymore; it’s become a necessity.”

Sanchez and others gathered at Washington Union High School in Easton as part of a “digital access conference.” The event included Assemblymember Dr. Joaquin Arambula, the Children’s Movement of Fresno, and All Children Thrive.

Broadband internet access in communities like Easton remains slow and expensive.

Speakers at the events said connectivity issues hamper students, teachers, and business owners.

Funding remains one of the largest roadblocks to achieving digital equity.

Some fear the state’s forthcoming Digital Equity Plan won’t reflect the challenges in Fresno County.

In fact, Mike Espinoza, the executive director of The Children’s Movement of Fresno, said funding issues could get worse.

Espinoza said the California Department of Technology relies on maps from the Federal Communications Commission that are “flawed” and “incomplete.”

“We know that the State’s Digital Equity Plan will outline its planned investments by county,” Espinoza said. “Though we fear that the state’s overreliance on the incomplete FCC/CPUC data will motivate them to avoid investing in Fresno’s digital infrastructure.”

Additionally, Wednesday’s gathering came just a day before the Fresno City Council is expected to vote on a resolution to “foster equality for Fresno residents and bolster resources for upward mobility.”

Arambula promised to stand by the affected communities and push for a solution at the state capitol.

“For us to build a stronger future, we need to be listening to residents to address those digital divides and inequities head on,” Arambula. “We need to make sure that every one of our residents feels that ability to connect to internet that’s high speed and that works to address the issues that our economy demands.”

The post ‘Not a luxury.’ Fresno County residents call for major investments in broadband internet access appeared first on Fresnoland.

A national cannabis products manufacturer is preparing to open a new production facility in Alleghany County to help supply Virginia’s medical marijuana market.

Chicago-based Green Thumb Industries’ products include botanical cannabis — the basic flower form of cannabis — as well as cannabis-based items such as muscle rubs, tinctures and edibles. It already operates a manufacturing facility in Abingdon and RISE Dispensary medical marijuana locations in Abingdon, Bristol, Christiansburg, Danville, Lynchburg and Salem.

In Alleghany County, GTI is in the final stages of construction work at a recently purchased 300,000-square-foot building. The company declined to say how much it has invested in its new facility.

The company anticipates launching its manufacturing operation there “within the next month or so,” said Jack Page, GTI’s market leader in Virginia.

“It is a rather large building and we are technically only going to be occupying a portion of the building to start with,” Page said. “Market demand will really determine how much of the facility is actually used. This is in response to needing additional space outside of our Abingdon facility.”

The Alleghany site will be used to cultivate cannabis, with different rooms for growing, maturing and drying the plants, as well as places to store nutrients. Material will then be sent to the company’s Abingdon site to be processed into products.

The company plans to start with about 40 employees at the new site. They’ll work in a variety of jobs including “plant-touching roles” such as flower technicians, but also in custodial, maintenance and human resources roles, Page said.

Those jobs will provide attractive new opportunities for Alleghany County residents who might not have previously considered manufacturing employment, said John Hull, executive director of the Roanoke Regional Partnership, an economic development organization that helped connect GTI with resources related to workforce recruitment and training as the company considered the location.

“It’s a great career ladder type of opportunity as well,” Hull said. “For instance, young workers can take a role there, learn the manufacturing type of skills, be introduced to that type of environment and then be available for growth in that company but also other opportunities in the larger region.”

Green Thumb Industries has more than 4,000 employees across the company. The Alleghany site will be its 19th manufacturing facility, and it has more than 80 dispensaries across more than a dozen U.S. markets. It entered the Virginia market in 2021 with the purchase of Dharma Pharmaceuticals, of which Page was a co-founder.

In May, the publicly traded company reported a first-quarter net income of $9.1 million, or 4 cents per share, on $248.5 million in revenue. In an earnings news release, the company noted its revenue was up 2% year over year and said it holds a $185 million cash balance to invest in further expanding its business. It next reports quarterly earnings on Aug. 8.

While GTI has a national presence, all of the products made at the Alleghany facility will serve the Virginia market, Page said.

“Because of the way the federal government still views cannabis, nothing can cross state lines,” he said. “Anything sold in the Virginia medical program is grown and processed and fully sourced in Virginia. And nothing that is made in Virginia is going out of state to another facility.”

Despite state legislation passed in 2021 that allows adults in Virginia to possess small amounts of marijuana for personal recreational use, as well as grow up to four marijuana plants at their own homes, there currently is no licensing or regulatory framework to allow retail sales in the commonwealth.

That means medical dispensaries remain the legal way for Virginians to purchase marijuana, Page said. Qualifying medical patients need a certification from a doctor, physician assistant or nurse practitioner, plus a valid government ID, to buy cannabis at a medical dispensary.

“The RISE Dispensaries and our counterparts in other parts of the state are the safe way for Virginians to access cannabis,” Page said. “Absent the retail market, there are some dispensaries out there that are providing access to cannabis but not necessarily in a safe manner. That’s an important distinction that I think needs to be made.”

GTI is regulated by the state Board of Pharmacy and, beginning Jan. 1, the Virginia Cannabis Control Authority. The company’s facilities are inspected for compliance with procedures such as those related to inventory and record-keeping, and third-party labs check for the presence of pesticides and heavy metals in products, Page said.

GTI’s location in the Alleghany Regional Commerce Center — a business park between the city of Covington and the town of Clifton Forge, just off Interstate 64 — makes it a good location for distributing products statewide, said Alleghany County Administrator Reid Walters.

If the federal government were to legalize marijuana, GTI would also be well-positioned to ship products into the Midwest, Walters said.

“Legalization is something that’s going to create jobs in Alleghany County and put food on people’s table, and they’re well-paying jobs,” Walters said.

Page said the possibilities for business expansion — whether that’s due to higher demand in Virginia’s medical market or due to potential legalization of recreational sales — “definitely factored into the decision to purchase the Alleghany facility.”

Still, the path to increased legalization, both at the state and federal level, remains unclear.

President Joe Biden last year pardoned all federal offenders convicted of simple marijuana possession and urged state governors to do the same. He also instructed federal officials to review how marijuana is classified under federal law.

But the president has stopped short of formally backing federal marijuana legalization, and pot remains a Schedule I controlled substance at the federal level.

In Virginia, a member of Gov. Glenn Youngkin’s administration said earlier this month the governor is “not interested in any further moves towards legalization of adult recreational use marijuana,” according to The (Charlottesville) Daily Progress.

Nonetheless, Green Thumb Industries is looking ahead to the debut of its Alleghany County facility, which, along with the launch of its newest RISE Dispensary in late June in Danville, will further boost the company’s ability to supply the commonwealth with medical cannabis.

Hull, of the Roanoke Regional Partnership, called the new facility a “truly exciting” opportunity for the Alleghany Highlands.

“It further diversifies their industrial base, and combine that with the career-building opportunities there for young workers in the area, we think that it truly is an impactful opportunity,” he said.

The post Cannabis manufacturer to open growing facility in Alleghany County appeared first on Cardinal News.

A 100-foot-wide dam break at Archusa Creek Water Park unleashed a deluge in Quitman, Miss., on Sunday evening.

The post Dam Break At Archusa Creek Water Park Unleashes Flood in Quitman appeared first on Mississippi Free Press.