Toxic Nuclear Waste is Piling up in the U.S. Where’s the Deposit?

Decades on end and after spending billions, the U.S. still has no strategy to permanently deposit its highly radioactive nuclear waste.

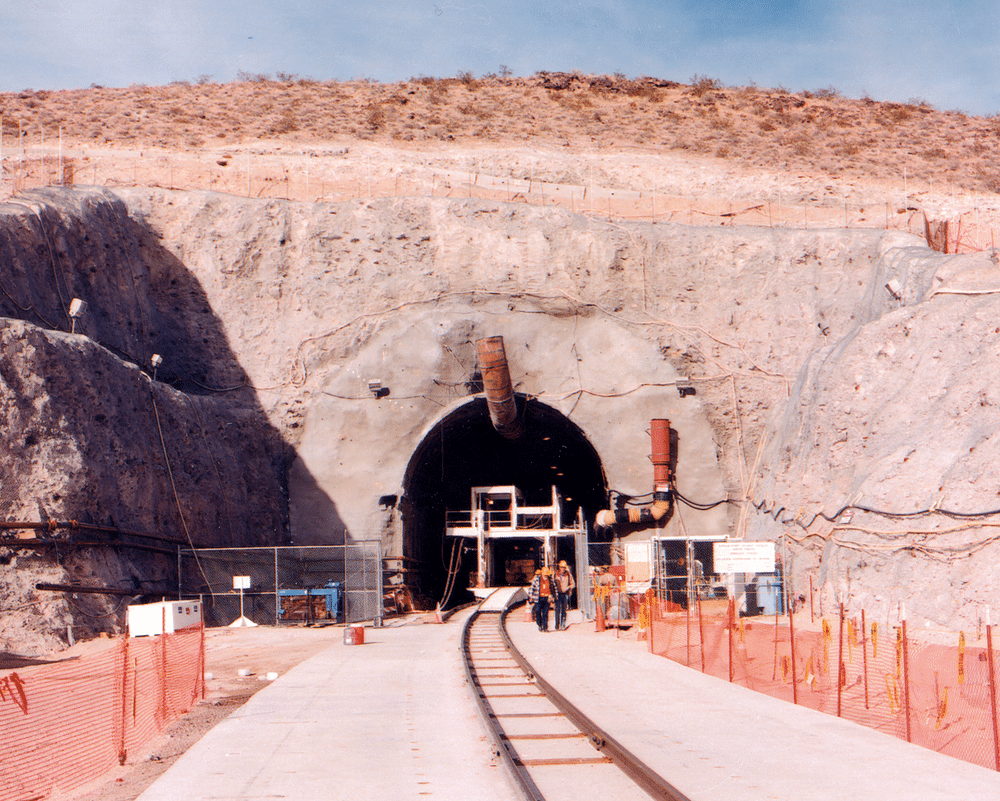

Some 90 miles northwest of Las Vegas, deep in Southern Nevada, lies a multibillion-dollar hole.

Twenty years ago, the George W. Bush government formally chose the dry, arid landscape to build a tunnel complex. The Yucca Mountain project would have been the place to deposit up to 70,000, or more than 75% of the 90,000-and-growing metric tons of highly radioactive spent nuclear fuel coming from commercial reactors in the country. Yet, almost from the onset, locals and politicians resisted the project because of what it would entail: a constant stream of nuclear waste coming into Nevada from where they are currently stored, hundreds of miles away. (Only one of the 75 sites with currently operating nuclear plants are even located within the Mountain States, an eight-state region including Nevada that spans nearly 900 thousand square miles across the Rockies.) And so, between 2009 and 2010, the Obama administration kept its campaign promise and stopped the project.

“I just didn’t like it. It was too much danger in nuclear radiation leaks. And, it just didn’t

make sense. Then, the safety aspects […] I don’t know quite how to put it, it just didn’t make sense to transport that kind of stuff through this area when the areas that were keeping it couldn’t just keep it in their own backyard.”

“I don’t know quite how to put it, it just didn’t make sense to transport that kind of stuff through this area when the areas that were keeping it couldn’t just keep it in their own backyard.”

Barbara and Ken Dugan lived near Crescent Valley, Nevada, back in 2011. The events of the Fukushima meltdown were fresh on everyone’s minds. They were speaking to Abby Johnson, then the Nuclear Waste Advisor for Eureka County who worked on collecting opinions from local communities after the Yucca Mountain project shut down.

Another decade on, the U.S. still has no solid solution for its nuclear waste. Nuclear power leaves a small carbon footprint compared to other types of energy. Still, the question of managing its waste is complicated. Nuclear waste can stay radioactive from a few hours to hundreds of thousands of years. Therefore, scientists and the industry agree that the best long-term solution is to bury the waste underground in large, heavily engineered repositories while it remains unsafe. But building these sites seems to be a difficult endeavour, and the U.S. isn’t the only country struggling to get it done.

Out of the 32 nations operating nuclear reactors today, only Finland is close to finishing a deposit. Countries like the U.K., where the first nuclear power station in the world to produce electricity for domestic use was built, are struggling with finding a site in the first place. According to a 2018 report, “Reset of America’s Nuclear Waste and Management”, prepared by the Stanford University Center for International Security and Cooperation (CISAC) and the George Washington University Elliott School of International Affairs, for 50 years, governments and committees worldwide have launched at least 24 campaigns to create underground repositories. Still, in only five of these, committees managed to choose a site to work with. And so, the question arises: how come nations capable of technological breakthroughs like sending humans to space can’t seem to find a place for their radioactive waste?

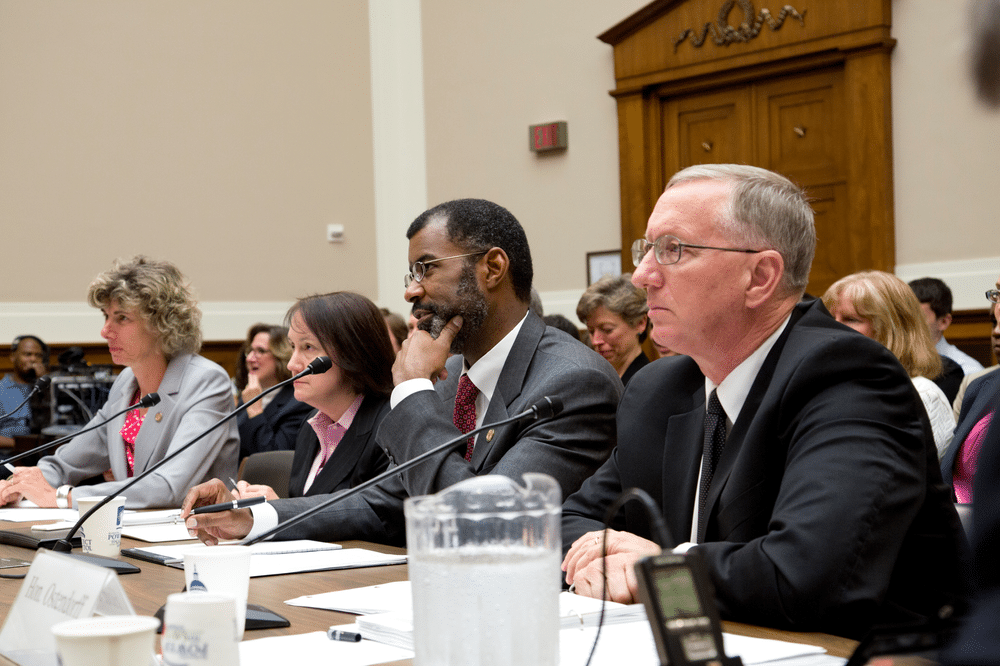

A lack of policymaking consistency hasn’t helped the nuclear waste cause on American soil; that’s what Rodney Ewing — co-director of CISAC and the former chairman of the U.S. Nuclear Waste Technical Review Board who reviewed the Department of Energy’s efforts to manage and dispose of nuclear waste during the Obama administration— thinks is part of the answer.

According to him, the Nuclear Waste Policy Act of 1982, which represented the path forward in managing nuclear waste in the U.S., kept changing throughout the 80s and 90s. For example, congressional amendments in 1987 specified Yucca Mountain as the sole candidate site instead of allowing for multiple candidate sites to be considered. More recently, the ongoing chaos of re-funding and re-defunding Yucca Mountain by the Trump administration made it challenging to convince anyone. “The more you keep changing direction, or changing the rules, the less trust you can count on from candidate communities. The lower the probability that you will be successful”, he adds.

“The more you keep changing direction, or changing the rules, the less trust you can count on from candidate communities. The lower the probability that you will be successful”

Ewing believes the country needs cohesiveness and an independent organization to move forward — perhaps in a manner similar to the Tennessee Valley Authority, as recommended by the Blue Ribbon Commission on America’s Nuclear Future in 2012, or a non-profit, nuclear utility-owned implementing corporation, as suggested in the 2018 CISAC report.“In the past, Yucca Mountain suffered from the fact that the Department of Energy wears many hats, everything from fossil fuels, solar, nuclear, nuclear weapons, and so on. Somehow, in that broad context, developing a geologic repository was low on the [priority] list.”

Another hurdle that has made this project an uphill battle in the U.S. is the bungling of public engagement. Unlike the NIMBY battles unfolding across the country that are snarling public transit, solar farms, or less-carbon-intensive forms of housing, Yucca Mountain falls on Western Shoshone territory, where Indigenous residents are still dealing with the consequences of resource extraction and nuclear testing by the federal government without their full consent, leading to their sustained opposition to the project. This is not to mention other local fears about the toxicity levels of a deposit, the permanence of the project (radiation levels were expected to be regulated for the next million years), and the impact it might have on property and land values. “The state of Nevada has not been willing to accept this possibility [of a nuclear waste deposit]. And so, the federal government has dealt with a state that doesn’t want the repository. That’s a social issue”, says Ewing.

To minimize public outcry, it’s key that a site is decided voluntarily: a community states they’d accept a nuclear waste site in their area, and only after initial conversations should projects start. This is one of the reasons Finland ended up being successful with their project when the local authority voted overwhelmingly in favour. Yet, according to Pasi Tuohimaa, the Communications Manager at Posiva — the company responsible for managing radioactive waste in Finland —there’s more to the whole process. Culture takes center stage when choosing a site. He told The Xylom that communities where nuclear power plants had been active for decades tend to be more accepting of hosting a nuclear waste site. “If you have a strong nuclear identity, if you have a site where there’s been a power plant for 40 years or 45 years, then people know […] a lot about radiation, they know about radiation safety”. He also mentions that Finns, in general, want to solve the issue of nuclear waste rapidly not to harm future generations. “The Finnish people believe that if our generation has created [nuclear waste], then it’s our generation’s duty to take care of the waste and not leave it for the solidarity of future generations”, he adds.

“The Finnish people believe that if our generation has created [nuclear waste], then it’s our generation’s duty to take care of the waste and not leave it for the solidarity of future generations”

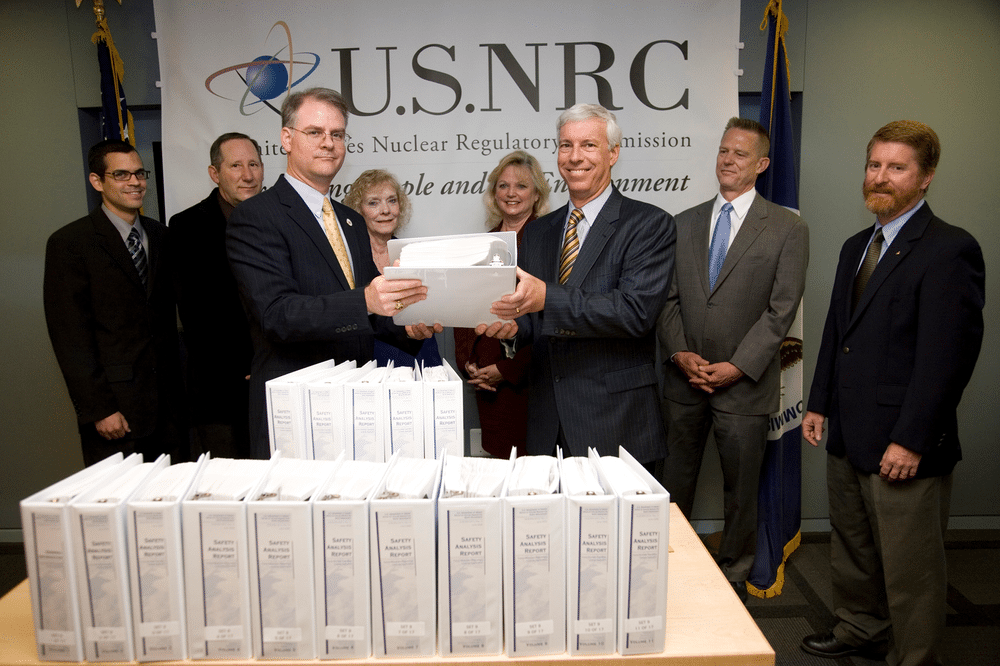

Other nations like Canada and the U.K. are now moving forward with strategies in which communities host deep geological repositories voluntarily. The Biden administration is also moving forward with a consent-based siting approach; however, the aim is to make storage sites, not geological repositories15,18. This means waste will be stored for some time but not in the long term: a permit issued by the Nuclear Regulatory Commission in May to build and operate one such facility in southeastern New Mexico is valid for only 40 years. Ewing is skeptical of such an approach.“I call it indefinite storage. And I would say indefinite surface storage of highly radioactive waste […] is not a very attractive solution. It’s not a solution.”

Building deep geological repositories is crucial to safely deposit nuclear waste despite being a tall task. As other western Nations inch closer to having their own sites, it remains to be seen whether the U.S. has the will to drive a much-needed site forward, or whether it is content with kicking the can down the road — until the country buckles under this mountain of a problem.