Big Island Police Tackle Cockfights But The Real Catch Is On The Sidelines

Hawaii County Police Chief Ben Moszkowicz says officers target cockfights where the stakes are highest.

Hawaii County Police Chief Ben Moszkowicz says officers target cockfights where the stakes are highest.

For the past seven years, the City of Phoenix has recognized Indigenous Peoples’ Day instead of Columbus Day every second Monday of October, but it was never an official city holiday.

But now that’s changed. With a vote of 7-1, the Phoenix City Council made it official, and Indigenous Peoples’ Day has been designated a city holiday.

“This is really exciting,” said Democrat Councilwoman Laura Pastor, of District 4, during a city council meeting on April 19.

Pastor said she’s been working with Indigenous communities to declare this resolution and to introduce one involving land acknowledgment, which is the acknowledgment that the city rests on the ancestral homelands of Indigenous people.

The Phoenix City Council on April 19 approved the resolution to declare the second Monday in October of each year as a designated city holiday known as Indigenous Peoples’ Day.

“This is an exciting item that has been many years in the making,” Phoenix Mayor Katie Gallego said during the council meeting. She talked about how Indigenous Peoples’ Day was originally only recognized as a day, but this vote makes it a full city holiday.

“Phoenix is proud to recognize the roots on which our city was founded,” Gallego tweeted after the resolution passed.

During the council meeting, only one city council member questioned the resolution: Republican Councilman Jim Waring, of District 2.

Waring voiced his concern about the cost of the city holiday and questioned exactly how much it would be for the city to create an additional holiday.

Assistant City Manager Lori Bays answered his question, saying that an additional city holiday would cost the city approximately $1.5 million from the general fund and approximately $2 million from all funds.

Waring questioned whether the city planned to take away an additional holiday because it would be revenue neutral if one holiday was swapped for another.

Bays said no other city holiday would be taken away. If so, that decision would be up to the Phoenix City Council to make in the future, because the resolution proposal was to add Indigenous Peoples’ Day as a holiday without removing any other holiday.

By declaring Indigenous Peoples’ Day a city holiday, Waring said the city was asking taxpayers not to have the city open for another day and to pay $2 million for the privilege.

The resolution passed 7-1, and Waring was the only one to vote against it.

This means that Phoenix City Offices will be closed, and it will be a paid holiday for full-time city employees. It will be added to the 12 other recognized city holidays.

The State of Arizona does not recognize Indigenous Peoples’ Day as an official holiday. In the past, state officials have introduced resolutions to officially recognize the day across Arizona, but those have never passed through the legislature.

When Laura Medina heard the City of Phoenix will officially recognize Indigenous Peoples’ Day as a city holiday, she commended the decision by saying it was “amazing and awesome.”

“It’s great that there are these movements going on,” Medina said.

Medina is an organizer with the nonprofit Matriarch Ways, which was originally called Indigenous Peoples Arizona. The group has been hosting celebrations of Indigenous Peoples Day since 2015.

But, Medina wondered if the city holiday will go beyond being performative. Medina said she can’t help but ask if this is really abolishing Columbus Day.

“Is that really abolishing the idea of what this individual represented?” Medina asked. “I do know that there is a lot that needs to happen.”

She is hopeful that the City of Phoenix’s move to make Indigenous Peoples’ Day an official city holiday will spread and that people will get the day off to reflect on the land that they live on.

Medina hopes that people don’t treat the day as if it’s just another vacation day but rather use it as an opportunity to connect and acknowledge the Indigenous communities within their community and understand that they are living on stolen land.

“Pay respect to the original people who call this place home,” Medina said.

She hopes people take the time to understand the struggles that Indigenous communities are actively facing, from the militarization of the border to the disrespect and destruction of their sacred sites.

Matriarch Ways hosts an Indigenous Peoples’ Day celebration every October and other workshops or events geared toward Indigenous communities. For more information about their work, visit their website.

The post Phoenix designates Indigenous Peoples’ Day a city holiday appeared first on Buffalo’s Fire.

He calls it the “tin can.” Its heater is broken. The cold creeps through its thin walls. Wind rattles the wooden cabinets. But it’s all he could afford.

A year ago, two runaway fires set by the U.S. Forest Service converged to become the Hermits Peak-Calf Canyon wildfire. It rode 74 mph wind gusts, engulfing dozens of homes in a single day as it tore through canyons and over mountains.

The blaze became the biggest wildfire in the continental United States in 2022 and the biggest in New Mexico history. And it was the federal government’s fault: An ill-prepared and understaffed crew didn’t properly account for dry conditions and high winds when it ignited prescribed burns meant to limit the fuel for a potential wildfire.

By the time the blaze was fully contained in August, it had destroyed about 430 homes, according to the Forest Service. Monsoons helped extinguish the fire, but they spurred floods that caused more damage.

FEMA stepped in to help, offering cash for short-term expenses and, after the state requested it, temporary housing to 140 households. But the federal government has acted so slowly and maintained such strict rules that only about a tenth of them have moved in, an investigation by Source New Mexico and ProPublica has found.

A year after the fire began, FEMA says most of the 140 households it deemed eligible for travel trailers or mobile homes — essentially, people whose uninsured primary residences sustained severe damage — have found “another housing resource.”

What the agency doesn’t say: For some, that resource is a vehicle, a tent or a rickety camper. It’s a friend or relative’s couch, sometimes far from home. It’s a mobile home paid for with retirement funds or meager savings.

The fire upended a constellation of largely Hispanic, rural communities that have cultivated their land and culture in the shadows of the Sangre de Cristo Mountains for hundreds of years. Many residents can find their family names on land grants issued by Mexican governors in the 1830s.

Now they’re dispersed across the region, even out of state. Source New Mexico and ProPublica obtained records from local officials and volunteer groups and eventually interviewed more than 50 people who between them lost 45 homes.

Many of them said FEMA’s trailers were offered too late, cost too much to get hooked up or came with too many strings attached. Several said they went through multiple inspections, only to learn weeks later that one rule or another made it impossible to get a trailer on their land. In some cases, FEMA officials told people that their only option was a commercial mobile home park, miles down winding, damaged mountain roads from the homes they were trying to rebuild.

People who between them lost 17 homes said they withdrew from the housing program because of those problems.

As of April 19, just 13 of the 140 eligible households had received FEMA housing. Only two of them are on their own land.

Martinez said he got a call from FEMA in mid-October, seemingly out of the blue. By then, he had been living in the tin can for a couple of months. As temperatures dropped, he had started sleeping on the couch, closer to the space heater.

A FEMA representative asked if he needed a trailer to live in.

“I told them it was too late,” he said. “Way too late.”

FEMA said terrain and weather, among other factors, presented challenges in providing housing to survivors. But the agency said it made an exception to its rules by providing trailers and mobile homes in the first place — normally such programs are reserved for disasters that displace a large number of residents.

The agency said it tries to place temporary housing on people’s property, but couldn’t in many cases because of federal laws and its own requirement that trailers be hooked up to utilities. State and local officials have asked the agency to loosen its rules, but it hasn’t.

FEMA knows it has a problem with its response to wildfires. A 2019 Government Accountability Office report said FEMA’s housing programs are better suited to help those displaced by hurricanes and floods because some victims can remain in their damaged homes, there’s often more rental housing in those areas and there’s more space for large mobile home parks than there is in the rugged mountains scorched by wildfires.

FEMA agreed with the findings and said it would explore providing housing funding to states because they’re better positioned to guide recovery. That didn’t happen after the Hermits Peak-Calf Canyon fire.

Last month, Martinez woke up on the couch in severe pain from a swollen bladder. Now he needs frequent medical appointments to check his catheter and figure out what’s causing the pain. His sister has been trying to get him a FEMA trailer in a commercial park closer to a clinic in the town of Mora. It’s just 8 miles away, but it can take 45 minutes to drive there.

What neither of them knew when he bought that old trailer last summer is that doing so made him ineligible for a FEMA trailer.

Martinez wants to stay on his property if he can. His great-grandfather once owned the land where he built that cabin. He raised his hands to show his stiff, swollen fingers. “They ain’t worth shit now,” he said. “But a man builds his own castle, right?”

By mid-June, firefighters had finally started to get the blaze under control, and people were being allowed back into communities in the area known as the burn scar. New Mexico officials turned their attention to those who had nothing to return to.

Kelly Hamilton, deputy secretary for the state Department of Homeland Security and Emergency Management, told FEMA in a letter that people were living in their cars, at work and in churches, in campers and even in tents.

He asked FEMA to provide travel trailers or mobile homes. “If the housing situation is not immediately addressed, the survival of each community is bleak,” he wrote.

“If the housing situation is not immediately addressed, the survival of each community is bleak.”

He cited an analysis showing there was just one rental apartment available in Mora and San Miguel counties, the two hardest hit by the fire. He noted that roughly 20% of residents in those counties were below the poverty line and that one-third of Mora County residents were disabled, according to U.S. Census Bureau figures.

It took FEMA a month to approve Hamilton’s request and about two weeks more to tell the public. On Aug. 2, the agency announced it would launch a small housing program, which “will likely entail placing a manufactured home on the resident’s property for the length of time it takes to rebuild.”

But there were strict rules for where those trailers could go. Recipients would need to have electrical service, septic tanks and drinking water close to the housing site. The agency’s draft contract for the housing program specified details down to the width of straps that were required to secure trailers against wind.

Local and state officials and disaster survivors told Source and ProPublica that the utility requirements were unreasonable, especially in this area. It’s common for homes to be heated with wood stoves fed with timber harvested from the surrounding land. Some people didn’t have running water or septic tanks even before the fire. Electrical outages were common in remote areas.

Martinez’s cabin never had running water; he got it from his neighbor’s well. So even if FEMA had offered him a trailer earlier, he would have had to pay thousands of dollars to build a well — if he could’ve found someone to do it.

FEMA is “very efficient in deeming people ineligible.”

“I’m trying to put this diplomatically,” said David Lienemann, spokesperson for New Mexico’s emergency management department. FEMA is “very efficient in deeming people ineligible.”

The effect of those rules is clear. As of April 19, FEMA said 140 households were eligible for trailers, as determined by the agency’s own inspections and policies. Of those, 123 had “voluntarily withdrawn.”

People dropped out because they “opted to live in their damaged homes, located another housing resource or declined all Direct Housing options,” said FEMA spokesperson Angela Byrd in an email. “However, those households remain eligible for the program should their situation change.”

FEMA wouldn’t allow Vicki Garland to connect a trailer to her solar panels, which weren’t touched by the flames. Instead, the agency insisted that she connect to the power grid, which would’ve cost her about $20,000. She’s now moving to the outskirts of Albuquerque, about 140 miles away.

Six individuals and families said they left the program because it would’ve cost too much to hook a trailer up to electricity, restore their wells or meet other utility rules.

Emilio Aragon was living in his office when he was told he was third on the list for a FEMA trailer. After waiting six months, he gave up and spent his retirement savings on a mobile home. He was among six individuals and families who said they were offered housing too late or faced delays that forced them to find housing on their own.

In response to those accounts, FEMA said in a written statement that it must ensure housing is safe and secure. “Generally, this is not a fast process because it requires us to be so thorough and meticulous. Working during the monsoon season meant it took additional time to make sure these sites were safe.”

FEMA has had a hard time getting people into temporary housing quickly after disasters. After Hurricane Ida struck Louisiana in 2021, FEMA said its housing program “is not an immediate solution for a survivor’s interim and longer-term housing needs” because it takes months to get sites ready. The agency praised Louisiana’s decision to launch its own federally funded housing program alongside FEMA’s.

A few months after the storm, The New York Times reported, the state’s program had housed around 1,200 people in about the same time it had taken for FEMA’s program to house 126.

Because FEMA’s housing programs end 18 months after a disaster declaration, every delay runs down the clock. Unless the Hermits Peak housing program is extended, it will expire in November, when the next winter is approaching.

FEMA declined to say whether it would extend the program, saying it would work with the state to meet survivors’ needs.

Wesley Bennett and his wife, JoDean Williams Cooper, said they went through three inspections to see where a trailer could be placed on their property. No spot was suitable, and they were instead offered a site at a mobile home park. Five other individuals and families said they pulled out of the housing program because of the red tape.

FEMA has noted that nine households declined to live in a mobile home park. Several of the trailers it has installed at those sites stand empty.

Some survivors, including Bennett and Cooper, said it wasn’t feasible to live in a trailer park an hour away from the homes they were rebuilding, especially with so many roads washed out by the flooding that followed the fire. They needed to stay on their land to take care of crops and deter theft.

“People who have largely lived in a rural setting are not going to be as comfortable in a trailer park. It’s just their whole way of life,” said Antonia Roybal-Mack, a lawyer who’s from the area and is assisting hundreds of victims in filing administrative claims for damage with the federal government.

Erika Larsen and her partner, Tyler White, were living in a camper van after losing their home in the village of San Ignacio when they learned FEMA was offering temporary housing.

Their livelihoods depended on being on their land, they said. Larsen is an herbalist who before the fire made tinctures and elixirs with ambrosia, hops and nettle she grew in gardens dotting the property. White works in construction and gets a lot of her work from neighbors who know where to find her.

Early on, White was feeling optimistic. She posted to a private Facebook group of disaster survivors on Aug. 23, a day after a FEMA inspection.

“Amazingly enough, yesterday we were approved for a trailer to live in. There is only one place to put anything on our property because of flooding. Our well and septic are shot because of fire and floods so we didn’t think we’d qualify. But we did. We should get it in a couple months,” she wrote.

“All this is to say as much as it stinks dealing with FEMA,” she wrote, “as hard of a fight as it can be, you might just get something out of it.”

Two days later, she added something.

Their case manager had “asked us if we wanted to live in a FEMA trailer park. We told him we’d been approved for a trailer at home and he said there was no record of that. Here’s hoping it’s a paperwork issue!”

She and Larsen waited for word while living nearby in their camper van. By late August, afternoon storm clouds often formed over the mountains, bringing monsoons that seeped through the roof and flooded their land. They worried about further damage to their property while they were away.

Two weeks after her first post, White offered another update. FEMA said the proposed site was in a floodplain, so the couple wasn’t allowed to put a trailer there.

“Our case manager said lots of people have been saying they were told they were approved for a trailer just to be declined,” she wrote. “So the moral of my story is: If a bunch of FEMA people come and tell you you are getting a trailer, you still might not be eligible.”

“If a bunch of FEMA people come and tell you you are getting a trailer, you still might not be eligible.”

They appealed the decision, but more inspections over the next two months determined that other sites on their property were too far from a septic tank, well or electricity hookup.

The agency also apparently made an error in its denial: Inspection records provided by Larsen showed the proposed trailer site isn’t actually in the floodplain on the map that FEMA says it uses for such decisions.

FEMA officials declined to comment on particular cases without written permission from the people who’d filed the claims.

By early November, as temperatures dropped and a long winter loomed, they’d had enough and decided to move into a dilapidated mobile home on a neighbor’s property. The landowner used it for storage, but at least it had a wood stove.

Larsen likened dealing with FEMA to an abusive relationship. “It really has been the worst part of this whole experience for me,” she said. “I feel capable of doing the work of processing this trauma. But having to keep talking to these people that are just fucking with my mind is pretty intense.”

It wasn’t just residents who saw that the program wasn’t working. State and local officials asked FEMA to relax its requirements or make accommodations, but the agency didn’t budge.

After FEMA announced in early August that it would provide trailers, officials met with Amanda Salas, the planning and zoning director for San Miguel County, and told her inspections and approvals could take 10 weeks.

Across the burn scar, survivors were arranging inspections with caravans of contractors and FEMA employees who poked around their properties to evaluate possible sites.

In late-September, Salas cleared her desk, expecting a flood of building permit requests from residents seeking permission to place FEMA trailers on their land.

Getting people back was “number one,” she said in an interview. “I need them to be in a warm place, you know?”

The flood of permit requests never came. About 35 people expressed interest in FEMA’s housing program when she told them about it after they showed up in her office to ask questions about cleanup and rebuilding. Most withdrew due to bureaucratic hurdles and delays, she said. Her counterpart in Mora County said he observed the same thing.

FEMA spokesperson Aissha Flores Cruz said in an email that the agency respects survivors’ decisions not to apply.

In mid-October, Salas attended a meeting of local and federal officials. It was her first opportunity to talk to high-ranking FEMA officials in person, and she spoke up.

She told them it didn’t make sense to require electricity, wells or septic systems in a rugged area where people didn’t rely on those services before the fire. She asked FEMA to provide gas generators.

“It seemed like they heard us,” Salas said of the meeting. “But they didn’t do anything about it.”

“It seemed like they heard us, but they didn’t do anything about it.”

Meanwhile, state officials sought waivers for the utility requirements and urged FEMA to outfit homes with portable water tanks or composting toilets. The state wanted “to at least get people back in a safe, warm home, on their property,” said Lienemann, the state emergency department spokesperson.

On Dec. 19, as temperatures dropped to single digits in parts of the burn scar, the state had not heard back from FEMA about its request. Ali Rye, an official with the state Department of Homeland Security and Emergency Management, asked for a response and again requested that FEMA approve waivers for high-need cases.

Lienemann said FEMA told the state that it would make decisions on waiving rules on a case-by-case basis. The agency never made any exceptions.

FEMA said federal law doesn’t allow it to waive the rules for its housing programs. And Flores Cruz said FEMA funds cannot pay to reconnect or rebuild utilities because that would be “permanent work” funded through a program intended to be temporary.

Payment for permanent repairs falls to a special FEMA claims office created in January, but it hasn’t cut any checks to survivors yet. Congress set aside about $4 billion in compensation funds in acknowledgement of the federal government’s role in starting the fire.

Daniel Encinias is one of the two people who got trailers on their own land. Each month, a FEMA representative stops by and asks for proof that he’s trying to find permanent housing — one of the conditions of living in the agency’s trailers.

He tells them he’s waiting for a check from the $4 billion compensation fund. “The minute FEMA releases the money and gives me enough money to build my home back,” he said, “that’s when things are gonna get done.”

The claims office will handle such requests. It was supposed to start sending out money in early 2023, but the agency is behind schedule.

“I have to tell you, opening an office is hard,” claims office Director Angela Gladwell told a packed lecture hall of frustrated fire survivors at Mora High School on April 19.

FEMA said it now expects to open three field offices to the public this month and it is trying to make partial payments while it finalizes its rules. Case navigators — who are locals who know the communities, the agency pointed out — are reaching out to those who have filed claims for damages.

The throngs of FEMA employees who swarmed into the area last summer to offer short-term aid have moved on. Some survivors are in limbo, running low on disaster aid and lacking the money to rebuild.

For Rex “Buzzard” Haver, a disabled veteran, the first disaster has split into a tangle of smaller ones. After his home burned in May, his family spent nearly $64,000 on a mobile home — more than the roughly $48,000 he’s gotten from FEMA so far. He doesn’t have the money to install a wheelchair ramp.

The company that delivered his replacement home broke its windows, tore the siding and ripped off lights during delivery. But they won’t come and fix it until the county repairs the road to his house. Haver has no washer or dryer, and for months, his satellite TV provider kept calling to collect a dish that had melted into black goo.

Haver didn’t learn that FEMA was offering trailers until several months after his new mobile home arrived in July, according to his daughter, Brandy Brogan. Now he’s in hospice, and he’s struggling.

“He doesn’t feel that he has a purpose anymore,” Brogan said. “There’s nothing for him to do. There’s nowhere for him to go.”

On a recent snowy afternoon, just down the road from Haver, strong winds rushed past blackened trees and through gaps in David Martinez’s trailer. He raised his voice to be heard over the wind.

“I’ve never been a sick man,” he said, wincing. “Till lately.”

Martinez can hardly walk due to his medical problems. The once-avid outdoorsman spends most days sitting in the kitchenette, the space heater on full blast, watching hunting shows on a 16-inch television. He ultimately got $34,000 from FEMA in short-term aid, but he’s down to a few grand.

On a recent afternoon, his sister, Bercy Martinez, and her grand-nephew drove up the washed-out driveway to deliver groceries and bottled water, which she does a few times a week. She loaded her brother’s fridge. “This is very good,” she said in Spanish of the meatloaf she bought. “It’s not too spicy.”

She’d been asking FEMA for weeks about getting her brother a spot in a mobile home park so he doesn’t have to navigate the bumpy road that makes drives to the clinic so painful.

Two weeks ago, she reached a FEMA employee on the phone and asked if the housing program that had arrived too late for her brother could help him now. The answer, she said, was no. He’s no longer eligible because he has a place to live.

Patrick Lohmann is a reporter for Source New Mexico and a recipient of ProPublica’s Local Reporting Network grant. He reports from Las Vegas, New Mexico. We welcome reader letters. Email High Country News at editor@hcn.org or submit a letter to the editor. See our letters to the editor policy.

This story is the first in Fresnoland’s ongoing series taking a deep dive into how local governments have spent pandemic relief dollars from the federal American Rescue Plan program.

In 2020, the COVID-19 pandemic handed the Clovis Rodeo Association its first annual loss in a decade when it had to cancel its flagship event. After bringing the Clovis Rodeo back in-person with limited crowd capacity the following year, the association ended up with an even bigger annual loss.

Despite two years of deficits, the Clovis Horse Show and Festival Association, the nonprofit organization behind the rodeo, wasn’t at the brink of collapse — mostly because it had more than $1 million in cash heading into the pandemic.

But that didn’t stop the rodeo from applying to be a subrecipient of federal pandemic relief dollars through Fresno County. In June 2022, the Fresno County Board of Supervisors approved reimbursing the rodeo for 2022 expenses at the sum of $200,000, using federal relief funds.

“It’s going back to the next rodeo — the livestock, the security, the supplies,” said Ron Dunbar, the rodeo’s president. “Without that fund, we wouldn’t be able to do what we like doing, what we’re used to.”

While the county is allowed to use federal relief funds to address the negative economic impact of the pandemic on local businesses, it brings into question Fresno County’s process in awarding organizations funds through the American Rescue Plan Act (ARPA), a federal program which gave $350 billion to local governments across the country to rebuild their economies.

Fresno County officials did not assess whether organizations that applied for funding actually needed federal relief dollars in order to stay afloat, county staff told Fresnoland. County officials also did not develop a metric to evaluate organizations’ equity aims in order to evaluate their impact on underserved communities or to compare applicants with each other.

Over the last two years, the county got $194 million in ARPA dollars from the federal government. Eligible uses of the federal funds include revenue replacement for government agencies, premium pay for essential workers, upgrading water, sewer, and broadband infrastructure, and financial assistance to businesses dealing with the negative economic impacts of COVID-19. Local governments that receive funding can either use the funds themselves or disburse the funds to subrecipients — both of which Fresno County has done since last year.

The unprecedented infusion of cash for local governments had great potential to bridge equity gaps, considering it didn’t have the typical constraints of annual government budgets. Last year, President Joe Biden even put out a 301-page report on how the ARPA program was his first opportunity to advance equity through major legislation.

Fresno County received 47 applications from organizations seeking funding from its ARPA subrecipient program. In May 2022, four county staff members evaluated whether applications met eligibility requirements from the federal government, said county spokesperson Sonja Dosti. She added that the five county supervisors’ chief staffers also weighed in on the process, evaluating whether applications aligned with county guiding principles on how to spend federal relief dollars.

They forwarded a recommended list of organizations that should get funding to the county’s Ad-Hoc Committee on ARPA, which was composed of two people: supervisors Nathan Magsig and Steve Brandau.

The two county officials approved and sent a priority list of organizations to the Board of Supervisors, which they subsequently approved in June 2022. The Clovis Rodeo was one of the 22 organizations accepted into the program. It was also one of three event-centered subrecipients — including the Big Fresno Fair and the Turkey Testicle Festival.

Among the 25 programs that didn’t get funding, one sought to increase education on voting, digital literacy and broadband infrastructure for underserved communities. Another program sought to boost enrollment in public programs — like CalWORKs, Medi-Cal and CalFresh — for residents in geographically isolated parts of Fresno County.

After two consecutive years in deficit — losing about $265,000 over 2020 and 2021 — the Clovis Horse Show and Festival Association still had more than $930,000 in cash. That’s largely because over the five years prior to the pandemic, the rodeo earned an average of $1.56 million in annual revenue and took home an average of about $277,165 in annual profits, which it used every year to either plump its cash accounts or acquire more land or property, according to the rodeo’s tax documents obtained by Fresnoland.

Alfreda Sebasto, a spokesperson for the rodeo, emailed a statement to Fresnoland, explaining that the rodeo’s annual cash totals are not cash reserves, since they aren’t entirely retained throughout the year and are used for operational expenses required to put on the rodeo every year. Sebasto did not respond to a request for the rodeo's 2022 gross revenue and total expenses.

Fresno County’s selection process for ARPA subrecipient funding did not include comparing organizations to each other in terms of their current resources and whether that tied into their overall need for federal relief money, said George Uc, an ARPA analyst at Fresno County. Instead, the county’s process was mainly focused on assessing applications for whether they met guiding principles and priorities set by Fresno County officials, which include addressing negative outcomes exacerbated by the pandemic and its immediate impacts.

"It's not that one application is better than the other,” Uc told Fresnoland. “It was more of identifying those that wouldn't duplicate funding sources and achieve the board's principles."

Every organization that applied for funding had to explain how it would “promote strong, equitable growth, and racial equity among impacted communities in Fresno County.” In response to that equity question, the Clovis Rodeo stated it does not discriminate against anyone, strives to be a family-friendly event and has affordable tickets between $20 and $35, according to its application for subrecipient funding, which Fresnoland obtained through a California Public Records Act Request.

In its application, the rodeo did not highlight a specific community or underserved group that its programming would specifically benefit, but did note how doing “outreach to underserved audiences, local schools and all interested is a part of the Association's core mission.”

Uc said that equity was assessed across all 47 applications for ARPA funding, however, the county did not develop a metric to compare the rigor of each organization’s equity aims with each other. He added that equity was assessed by understanding how each organization would have a lasting, transformational impact if given federal relief dollars.

County staff understood the rodeo’s equity aims as generating $15 million in revenue for the region, which helps businesses that depend on the event to make profit. He also said the rodeo is a boon for hotels, since it brings people from all over — including Merced, Bakersfield and Los Angeles — to Clovis.

"I think looking at (the Clovis Rodeo) from travel, hospitality sectors — what it does — that's the equitable part of it,” Uc said.

Fresno County’s approach to equity with ARPA dollars has been strongly criticized in the past. The California Pan-Ethnic Health Network, a statewide health advocacy organization, researched and analyzed how 12 of California’s largest counties spent ARPA funds in 2021. It gave Fresno County the lowest score, an “F,” since the county hadn’t even acknowledged racial inequities or underserved communities in its 2021 ARPA recovery plan report.

“The Board of Supervisors came up with these broad principles of how they want to use ARPA funding on their website and there's no mention of equity at all in the broad principles,” said Weiyu Zhang, an associate policy director at the California Pan-Ethnic Health Network.

Since then, Fresno County seems to have improved its approach somewhat, Zhang told Fresnoland, because its 2022 ARPA recovery report is much more detailed in terms of highlighting racial groups in Fresno County and social vulnerability statistics. However, she added that nothing actually keeps counties in check for using ARPA dollars to address equity issues.

"There's really just the power of communities collectively calling out their elected officials to apply public pressure," Zhang said.

That’s not to say none of Fresno County’s ARPA dollars have been used to address equity gaps. The county earmarked about $5 million for improvements to water infrastructure in Mendota and Malaga.

Furthermore, in 2022, county officials earmarked $150,000 to improve a park in El Porvenir and earmarked another $1.6 million to improve the community center in Lanare — both of which impact two rural unincorporated communities in the county.

“It's thanks to persistence and the community being involved in this decision-making process that I believe this was able to happen,” said Mariana Alvarenga, a policy advocate with the Leadership Counsel for Justice and Accountability. “So really just applauding the community and thanking the county for really listening — but also encouraging them to be more critical in thinking about what more can be done in the county.”

Alvarenga said that includes addressing broadband issues and further unmet infrastructure needs impacting unincorporated communities. But by now, $170.9 million in ARPA dollars have already been allocated by the county's board of supervisors, leaving about $23 million up for grabs.

"It's frustrating to think about ARPA funding things like the Clovis Rodeo,” Alvarenga said. “We believe that there are more pressing needs that impact people's day to day lives that should be addressed with these funds.”

The post Why did Fresno County give the Clovis Rodeo pandemic relief funds? appeared first on Fresnoland.

The Montana House of Representatives voted on party lines Wednesday to discipline transgender Democratic Rep. Zooey Zephyr by barring her from the chamber’s floor, anteroom and gallery for the remainder of the 68th Montana Legislature, which is scheduled to end no later than May 5.

House Majority Leader Sue Vinton, R-Billings, who brought the motion to bar Zephyr, said the Missoula representative will be allowed to vote remotely but will not be allowed to speak during floor debates. Zephyr’s punishment will not apply to her work in committees, which will continue unrestricted, though most legislative action occurs on the floor at this point in the session.

The disciplinary action follows a protest of House Speaker Matt Regier’s decision to not recognize Zephyr during floor debates that erupted in the House gallery Monday. During the disruption, when protesters chanted “let her speak” and police began handcuffing people and removing them from the gallery, Zephyr remained on the floor, holding her microphone in the air.

“Monday, this body witnessed one of its members participating in conduct that disrupted and disturbed the orderly proceedings of the body,” Vinton said in support of her motion. “This member did not accede to the order of the speaker to come to order and finally to clear the floor and instead encouraged the continuation of the disruption of this body, placing legislators, staff and even our pages at risk of harm.”

Montana Highway Patrol officers arrested seven protesters on misdemeanor trespassing charges as they cleared out the galley on Wednesday. A joint force of riot police from the city of Helena and the Lewis and Clark County Sheriff’s Office was also present. Police citations state the protesters were removed from the gallery and charged with trespassing for disrupting legislative proceedings, but document no violence or property damage.

Almost a week before the protest, Zephyr told lawmakers they would have blood on their hands for supporting Senate Bill 99, legislation that restricts gender-affirming care for transgender youth — a reference, she’s said, to increased suicide risks for people who don’t have access to such medical treatments. Zephyr is the first openly trans woman elected to the Montana Legislature, and Republicans have brought multiple bills this session restricting and criminalizing transgender health care and expression.

Her remarks generated an immediate objection from Vinton and, later, a call from the hard-right Montana Freedom Caucus for Zephyr to be censured. In a Wednesday press release, the Freedom Caucus noted that it was the first to advocate consequences for Zephyr.

For several days after her remarks, Zephyr attempted to register to speak about bills before the House and Regier refused to recognize her, which is the speaker’s prerogative under House rules. Regier suggested he might recognize her again if she apologized, but Zephyr made it clear that wouldn’t happen.

“I have lost friends to suicide this year,” she said last week. “I field the calls from multiple families who dealt with suicide attempts, with trans youth who have fled the state, people who have been attacked on the side of the road, because of legislation like this. I spoke with clarity and precision about the harm these bills do. And they say they want an apology, but what they really want is silence as they take away the rights of trans and queer Montanans.”

The conflict came to a head on Monday, with protesters’ chants drowning out Regier’s attempts to bring the House to order after a vote to affirm his ruling. Republican justifications of the motion to censure Zephyr Wednesday have focused mostly on Monday’s events, rather than her remarks last week.

Zephyr, whom the speaker allowed an opportunity to speak on the floor Wednesday under the procedure for disciplining a member, defended Monday’s protest as an expression of disenfranchisement by her 11,0000 constituents.

“And when I continued to not be recognized, what my constituents and my community did is they came here and said, ‘That is our voice in this body. Let her speak,’” Zephyr said on the floor. “And when the speaker gaveled down the people demanding that democracy work, demanding that their representative be heard, what he was doing was driving a nail in the coffin of democracy. But you cannot kill democracy that easily, and that is why they kept chanting ‘let her speak,’ and why I raised my microphone to amplify their voices.”

Republicans on Wednesday pursued the motion to censure Zephyr under a combination of legislative rules and the Montana Constitution, which says a chamber of the Legislature can “expel or punish a member for good cause shown with the concurrence of two-thirds of all its members.”

Rep. Casey Knudsen, R-Malta, who chairs the House Rules Committee, said on the floor Wednesday that Zephyr “violated the collective rights and safety of 99 other members of this body, our staff, our pages and the public,” which he identified as “good cause” for punishment.

Other lawmakers from either side of the aisle also rose to explain their votes Wednesday.

Rep. Jonathan Windy Boy, D-Box Elder, said his uncle always told him to keep one thing in mind: “No matter who we are, that we are all equal under the eyes of almighty. And always remember, when you point your finger at somebody, look how many are pointing back.”

Windy Boy, whose first term in the Legislature was in 2003, said he’s seen lawmakers nearly come to blows on the floor with no consequence. He recalled an incident in 2013 when then-Senate President Jeff Essmann, R-Billings, refused to recognize Senate Minority Leader Jon Sesso, D-Butte. Democrats pounded their desks with coffee cups and other items in protest.

“We got up and we hit the desks, we almost got charged for messing up the state’s property,” Windy Boy said. “Why weren’t we disciplined at that time? We should have. I would have went to jail, and I would have been found guilty. We’re picking one person in this body for something she believes is right.”

Two Republicans who spoke — Knudsen and Hamilton Rep. David Bedey — had previously voted against upholding Regier’s decision not to recognize Zephyr, but showed an apparent change of heart following Monday’s protest.

“The behavior of [Zephyr] has been in the news for over a week,” Bedey said. “And I must admit [that] opinions concerning her prior utterances vary, even within my caucus. But today we’re not here to pass judgment on what might have been said or done before this past Monday, but rather to consider the specific actions that were taken on a specific day.”

Zephyr, he said, could have chosen to leave the floor with other lawmakers or attempted to “calm the crowd.”

A small gathering of protesters assembled outside the Capitol Wednesday. Legislative leadership preemptively closed both the House and Senate galleries, which the public is usually free to access to observe legislative proceedings.

The discipline imposed by the House Wednesday is likely unprecedented in the state’s modern history. In 1975, then-majority Democrats could not get adequate support for a motion to censure three Republican lawmakers regarding an alleged campaign practices violation. Before the ratification of the state’s 1972 Constitution — a time in Montana history when corruption was a fixture of the state’s political culture — there appear to have been several efforts to expel lawmakers, some successful. The first dates to 1897, when lawmakers voted to expel Martin Buckley of Jefferson County.

Regier, in a press conference following the House’s vote Wednesday, said restricting Zephyr from the floor is necessary to ensure the safety of the body and to maintain decorum.

“We’ve had multiple breaches of decorum,” Regier said. “We do every session, we have people from both sides of the aisle … that breach decorum” and they usually apologize and say they’ll stay within the rules moving forward. “We’re not going to treat one representative differently from the other 99,” he added.

Wednesday marked the second consecutive day in which the House did not vote on any legislation on second reading — the main hurdle bills face in each chamber. On Tuesday, Regier canceled the House floor session with no explanation. On Wednesday, the House adjourned shortly after the motion to punish Zephyr passed.

House Minority Leader Kim Abbott, D-Helena, on Wednesday defended Zephyr and criticized the “opportunity cost” of the motion to restrict Zephyr’s participation with so few days left in the session. The Montana Constitution caps the length of regular legislative sessions at 90 legislative days.

“We don’t have a state budget,” Abbott said on the floor. “We don’t have a plan for housing. We don’t have a plan for childcare. We don’t have a plan for permanent property tax relief. We don’t have a plan for mental health. We don’t have a plan for provider rates. And today we’re on this floor debating this motion and hopefully we can get back to work. I sure hope so.”

She described her vote against the motion as a vote supporting constitutional principles.

“You know what, I agree that you absolutely can do this — by rule, by the Constitution, by Mason’s [Manual of Legislative Procedure],” Abbott said on the floor. “But just because you can do it does not mean that’s the right choice.”

Mara Silvers contributed reporting.

The post House Republicans bar Democratic Rep. Zooey Zephyr for breaching decorum appeared first on Montana Free Press.

Wyoming Attorney General Bridget Hill and Gov. Mark Gordon oppose the secretary of state’s request to join their defense of the state’s abortion ban in an ongoing lawsuit.

Gordon and Hill, both defendants in the case challenging the ban, claim in a brief filed Tuesday that Chuck Gray doesn’t have legal standing, and that joining the case “in his official capacity” as secretary of state is contrary to Wyoming statutes.

“Public officers such as the Secretary of State ‘have and can exercise only such powers as are conferred to them by law,’” the filing states, citing the case McDougall v. Board of Land Commissioners of Wyoming.

“In Wyoming, the powers and duties of the Secretary of State are prescribed by the Wyoming Legislature,” the filing continues. “In his official capacity, Secretary of State Gray cannot intervene in this case unless a Wyoming statute authorizes him to do so.”

While Gray has argued he has standing given his role as successor to the governor and public records custodian, the defendants state neither give him authority to intervene or even participate in the trial.

Plaintiffs fighting for abortion access noted that potential intervenors could request to file amicus briefs in the case if denied the right to intervene. That option would allow them to share their perspective and evidence.

“In his official capacity, Secretary of State Gray cannot intervene in this case unless a Wyoming statute authorizes him to do so.”

AG/Governor filing in abortion ban case

Gordon and Hill, however, argue that Gray should not be allowed participation of any kind.

Ninth District Court Judge Melissa Owens has scheduled a hearing for May 24 at 1 p.m. to consider arguments from all sides for and against admitting the potential intervenors. Other defendants in the case have until May 1 to file a response to the intervenors’ request, and the intervenors have until May 19 to reply.

The governor and attorney general don’t oppose Right to Life of Wyoming or Reps. Rachel Rodriguez-Williams (R-Cody) or Chip Neiman’s (R-Hulett) requests to intervene in the case. The defendants do, however, “disagree with the intervenors’ apparent belief that this Court should hold an evidentiary hearing or a formal trial in this case and do oppose this Court granting them intervention based on the premise that such a hearing or trial is necessary.”

The case only involves “questions of law,” the filing states, which precludes the need for such a hearing or trial. That suggests the judge should only consider whether the new abortion bans are constitutional on their face, excluding information or evidence that goes beyond what’s needed to make that narrow determination.

Instead, defendants argue, the judge should issue a “summary judgment,” which would limit expenses for all parties.

The potential intervenors — excluding Gray — tried to intervene in the case over the state’s previous ban last year, but were denied. They appealed that decision to the Wyoming Supreme Court, but asked it to be dismissed in light of the 2023 ban that replaced the one from 2022.

Observers expect the case to ultimately be decided by the Wyoming Supreme Court, regardless of the outcome in district court, where it currently sits.

The post Gov., AG oppose secretary of state’s request to join abortion ban defense appeared first on WyoFile.

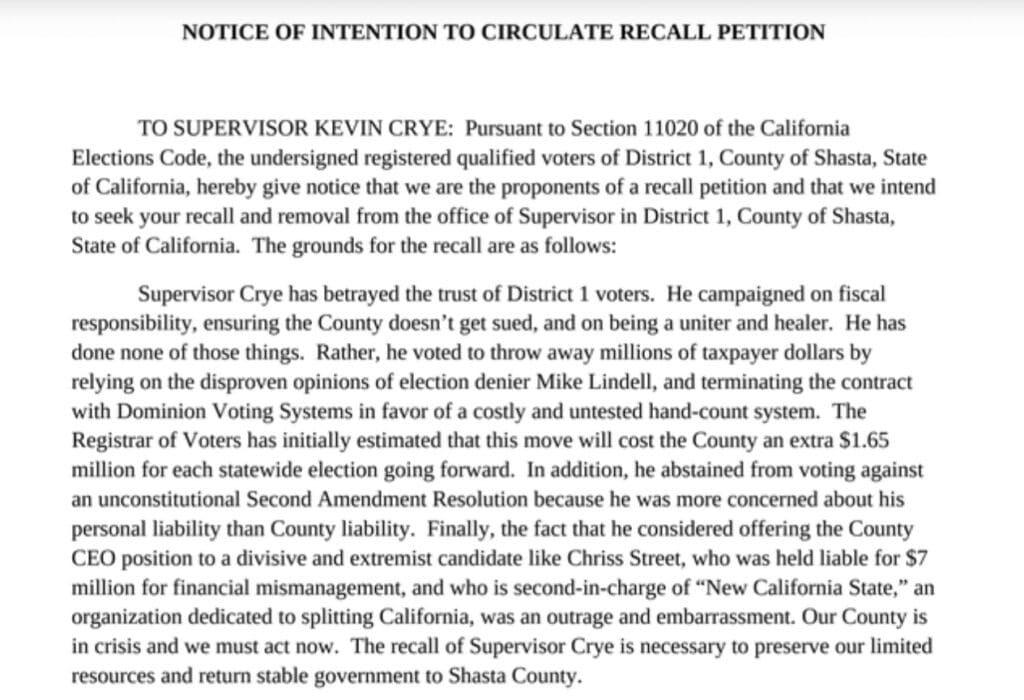

In 2022, prompted by the political shifts in Shasta County over the last few years, Kevin Crye ran for Shasta County Supervisor as a political newcomer, beating out his well-connected political adversary, Erin Resner, by only ninety votes.

Now, after only a few months in office, he’s facing a potential recall by community members who say his decisions have embarrassed and destabilized the County.

During the Tuesday, April 25 County Board meeting, community member Jeff Gorder presented a Notice of Intent to Recall Crye on behalf of the recently formed informal organization, Shasta County Citizens for Stable Government.

The attempted recall is primarily based on Crye’s support for changes to County election systems, decisions he’s made in tandem with two others on the five-member Board, Chris Kelstrom and Patrick Jones.

Recalling any of the three would change the Board’s majority, likely tilting future decisions in a different direction. But Crye may be the easiest target for a recall because of the narrow margin of votes with which he won office.

He represents the voters of District 1, the County’s geographically smallest and least rural District. During his campaign, he said he hoped his time in office would allow more voices to be heard and help heal a “hurting, fractured” County.

But his decisions to cancel the County’s contract for Dominion voting machines and move towards an unprecedented plan to hand count all future election votes seem to have worsened the County’s political divides.

As one of two new supervisors seated in January, Crye helped form a Board majority with a stated interest in reshaping the County around new priorities that included increasing trust in the elections process, rooting out government corruption, and reducing County staffing and costs.

The Board’s decisions since then have infuriated some community members, including those who’ve banded together as part of Shasta County Citizens for Stable Government.

Gorder says the group formed a few months ago when members of the community began meeting to discuss community concerns with recent Board decisions and actions that could be taken to address those concerns.

In a press release issued Tuesday, the group wrote that Crye’s political actions have gambled with their votes, wasted their money, and destabilized their home.

They’re concerned that Shasta County voters might be disenfranchised if plans to develop a new election system are not in place in time for the next election or don’t yield vote totals in time to comply with State law.

Some also worry about how County spending to fund that new election system will impact other County services. County Staff estimates that Supervisors’ plans to hand count votes will increase election costs by over $3 million just through the end of 2025. And that money will come from the General Fund, which means it will impact other budgeted programs and services.

Recall proponents are also angry that a majority of the Board voted to offer the County’s CEO position to Chriss Street, a controversial applicant best known as Vice President of New California, an organization which hopes to split the state in two.

The Board later rescinded that offer of employment after reviewing the results of Street’s background check. Street’s background includes being ordered by a federal judge to pay $7 million for mismanaging a trust fund.

When it comes to Crye specifically, recall proponents say his decision to consult on County election processes with MyPillow CEO Mike Lindell, who has been an outspoken proponent of claims of fraud in the 2020 election, further indicates his lack of qualification for County leadership. A few months ago, Crye traveled to speak with Lindell. He has confirmed that he’s billed his expenses for that trip to the County.

Gorder, speaking on behalf of the recall group, said while the reasons to recall Crye also apply to Kelstrom and Jones, community members have decided to focus on Crye in order to focus resources on the recall most likely to be successful.

“The positive response of District 1 voters to our informal polling and outreach efforts has been significant,” Gorder said.

“Our current effort is focused on changing the balance of power on the BOS. If we can shift one vote towards the “true conservatives,” i.e., the fiscally responsible, fact-based, commonsensical Republicans Rickert and Garman, we can bring back stable government to Shasta County.”

In a statement sent to Shasta Scout, Crye said the recall is “backed by liberal democrats” who have been planning it since before he was elected.

“As your Shasta County District 1 Supervisor,” Crye wrote, “I am proud of the work we have accomplished and will continue to serve the people of Shasta County.”

A statement by the Committee to Recall Kevin Crye, a subset of Shasta County Citizens for Stable Government, states that the group is made up of everyday citizens from a diversity of backgrounds, opinions, political affiliations, cultures and interests.

“The common purpose that unites us all,” the group wrote, “is that our elected officials follow the law, behave ethically and with common sense, and act responsibly as the stewards of our tax dollars.”

The Notice of Intent to Recall served on Crye this week is only the first step towards a recall election. Proponents will now attempt to gather the signatures of 20% (or 4,151) of Shasta County’s 20,757 District 1 voters. Should they succeed, an election to decide whether Crye is recalled would be held in November 2023 along with two other special elections.

According to Shasta County Clerk of Elections Cathy Darling Allen, if Crye’s recall is successful, his replacement will initially be appointed by California Governor Gavin Newsom, then later filled by County election, likely in November 2024.

Local businesswoman and former Redding City Council member Erin Resner, who narrowly lost to Crye in 2022, declined to comment on whether she would run for the position if Crye is recalled.

During his campaign, Crye referred to himself as a political outsider committed to fairness, truth, and honesty and determined to be a champion of the people’s voices.

Speaking to Shasta Scout before his election, Crye said he’s not an extremist and shouldn’t be lumped with other candidates just because he shares a similar platform or supporters. Crye’s campaign was indirectly supported by a political action committee funded by former County resident, Reverge Anselmo, who has also supported the campaigns of Jones and Kelstrom, among others.

See Shasta Scout’s campaign interview with Kevin Crye here.

If you have a correction to this story you can submit it here. Have information to share? Email us: editor@shastascout.org

This transcript has been edited for length and clarity.

California and Arizona are currently fighting each other over water from the Colorado River. But this isn’t new — it’s actually been going on for over 100 years. At one point, the states literally went to war about it. The problem comes down to some really bad math from 1922.

To some extent, the crisis can be blamed on climate change. The West is in the middle of a once-in-a-millennium drought. As temperatures rise, the snow pack that feeds the river has gotten much thinner, and the river’s main reservoirs have all but dried up.

But that’s only part of the story: The United States has also been overusing the Colorado for more than a century thanks to a byzantine set of flawed laws and lawsuits known as the “Law of the River.” This legal tangle not only has been over-allocating the river, it also has been driving conflict in the region, especially between the two biggest users, California and Arizona, which are both trying to secure as much water as they can. And now, as a massive drought grips the region, the law of the river has reached a breaking point.

The Colorado River begins in the Rocky Mountains and winds its way southwest, twisting through the Grand Canyon and entering the Pacific at Baja California. In the late 19th century, as white settlers arrived in the West, they started diverting water from the mighty river to irrigate their crops, funneling it through dirt canals. For a little while, this worked really well. The canals made an industrial farming mecca out of desert that early colonial settlers viewed as “worthless.”

Even back then, the biggest water users were Arizona and California, which took so much water that they started to drain the river farther upstream, literally drying it out. According to American legal precedent, whoever uses a body of water first usually has the strongest rights to it. But other states soon cried foul: California was growing much faster than they were, and they believed it wasn’t fair that the Golden State should suck up all the water before they got a chance to develop.

In 1922, the states came to a solution — kind of. At the suggestion of a newly appointed cabinet secretary named Herbert Hoover, the states agreed to split the river into two sections, drawing an arbitrary line halfway along its length at a spot called Lee Ferry. The states on the “upper” part of the river — Colorado, Utah, Wyoming, and New Mexico — agreed to send the states on the “lower” end of the river — Arizona, California, and Nevada — what they thought was half the river’s overall flow, 7.5 million acre-feet of water each year. (An acre-foot is enough to cover an acre of land in a foot of water, about enough to supply two homes for a year.)

This agreement was supposed to prevent any one state from drying up the river before the other states could use it. The Upper Basin states got half and the Lower Basin states got half. Simple.

But there were some serious flaws to this plan.

First, the Law of the River overestimated how much water flowed through the river in the first place. The states’ numbers were based on primitive data from stream gauges placed at arbitrary points on the waterway, and they took samples during an unusually wet decade, leading to a very optimistic estimate of the river’s size. The river would only average about 14 million acre-feet annually, but the agreement handed out 15 million to the seven states.

While the states weren’t able to immediately use all this water, it set in motion the underlying problem today: The states have the legal right to use more water than actually exists in the river.

And you’ll notice that the Colorado River doesn’t end in the U.S. — It ends in Mexico. Initially, the Law of the River just straight-up ignored that fact. Decades later, Mexico was squeezed into the agreement and promised 1.5 million acre-feet, further straining the already over-allocated river.

On top of all of this, Indigenous tribes that had depended on the river for centuries were now forced to compete with states for their share of water, leading to these drawn-out lawsuits that took decades to resolve.

But in the short-term, Arizona and California struck it rich — they were promised the largest share of Colorado River water and should have been primed for growth. For Arizona, though, there was a catch: The state couldn’t put their water to use.

The state’s biggest population centers in Phoenix and Tucson were hundreds of miles away from the river itself, and it would take a 300-mile canal to bring the water across the desert — something the state couldn’t afford to build on its own. Larger and wealthier California was able to build all the canals and pumps it needed to divert river water to farms and cities. This allowed it to gulp up both its share and the extra Lower Basin water that Arizona couldn’t access. California’s powerful congressional delegation lobbied to stop Congress from approving Arizona’s canal project, as the state wanted to keep the Colorado River to itself.

Arizona was furious. And so, in 1934, Arizona and California went to war — literally. Arizona tried to block California from building new dams to take more water from the river, using “military” force when necessary.

Arizona sent troops from its National Guard to stop California from building the Parker Dam. It delayed construction, but not for very long because their boat got tangled up in some electrical wire and had to be rescued.

For the next 30 years, Arizona and California fought about whether Arizona should be able to build that canal. They also sued each other before the Supreme Court no fewer than 10 times, including one 1963 case that set the record for the longest oral arguments in the history of the modern court, taking 16 hours over four days and involving 106 witnesses.

That 1963 case also made some pretty big assumptions: Even though the states now knew that the initial estimates were too high, the court-appointed expert said he was “morally certain that neither in my lifetime, nor in your lifetime, nor the lifetime of your children and great-grandchildren will there be an inadequate supply of water” from the river for California’s cities.

A few years after that court case, in 1968, Arizona finally struck a fateful bargain to ensure it could claim its share of the river. California gave up its anti-canal campaign and the federal government agreed to pay for the construction of the 300-mile project that would bring Colorado River water across the desert to Phoenix. This move helped save Arizona’s cotton-farming industry and enabled Phoenix to eventually grow into the fifth-largest city in the country. It seemed like a success — Arizona was flourishing!

But in exchange for the canal, the state made a fateful concession: If the reservoirs at Lake Powell and Lake Mead were to run low, Arizona, and not California, would be the first state to make cuts. It was a decision the state’s leaders would come to regret.

In the early 2000s, as a massive drought gripped the Southwest, water levels in the river’s two key reservoirs dropped. Now that both Arizona and California were fully using their shares of the river, combined with the other states’ usage, there suddenly wasn’t enough melting snow to fill the reservoirs back up. A shrinking Colorado River couldn’t keep up with a century of rising demand.

Today, more than 20 years into the drought, Arizona has had to bear the biggest burden. Thanks to its earlier compromise decades earlier, the state had “junior water rights,” meaning it took the first cuts as part of the drought plan. In 2021, those cuts officially went into effect, drying out cotton and alfalfa fields across the central part of the state until much of the landscape turned brown. Still, those cuts haven’t been enough.

This century, the river is only averaging around 12.4 million acre-feet. The Upper Basin states technically have the rights to 7.5 million acre-feet, but they only use about half of that. In the Lower Basin, meanwhile, Arizona and California are gobbling up around three and four million acre-feet respectively. In total, this overdraft has caused reservoir levels to fall. It’s going to take a lot more than a few rainy seasons to fix this problem.

So, for the first time since the Law of the River was written, the federal government has had to step in, ordering the states to reduce total water usage on the river, this time by nearly a third. That’s a jaw-dropping demand!

These new cuts will extend to Arizona, California, and beyond, drying up thousands more acres of farmland, not to mention cities around Phoenix and Los Angeles that rely on the Colorado River. These new restrictions will also put increased pressure on the many tribes that have used the Colorado River for centuries: Tribes that have water rights will be pressured to sell or lease them to other water users, and tribes without recognized water rights will face increased opposition as they try to secure their share.

And Arizona and California are still fighting over who should bear the biggest burden of these new cuts. California has insisted that the Law of the River requires Arizona to shoulder the pain, and from a legal standpoint they may be right. But Arizona says further cuts would be disastrous for the state’s economy, and the other five river states are taking its side.

Either way, the painful cuts have to come from somewhere, because the Law of the River was built on math that doesn’t add up.

This story was originally published by Grist with the headline The very bad math behind the Colorado River crisis on Apr 26, 2023.