Maui Faces Millions In Lost Revenue From Property That May No Longer Exist

Property tax payments are due on Aug. 21 but county officials haven’t said what their plan is for residents and businesses whose property is gone.

Property tax payments are due on Aug. 21 but county officials haven’t said what their plan is for residents and businesses whose property is gone.

The Hawaii utility has acknowledged the growing danger of wildfires and made some changes. But lawsuits are already pointing to the live power lines as a cause in Maui.

Local leaders say they were caught by surprise because the scale of Tuesday’s fire was unprecedented. But the warning has been sounded for years.

Fire season is underway in Montana, with a number of active fires burning more than 1,000 acres.

Wildfire crews are battling several on the Flathead Indian Reservation; with three of the largest fires being the Niarada, Big Knife and Middle Ridge fires.

A community meeting is planned for Thursday, Aug. 10 at the Arlee Community Center regarding the Niarada, Big Knife fires and another fire, the Mill Pocket fire.

The largest fire in the state is the Niarada and is burning west of Elmo on the northern end of the reservation. It was ignited by lightning on July 30.

The forest in the area involved in the fire includes a mix of timber, including some that is downed and dead. The area also has brush and shorter grass near the valley bottom, according to Inciweb, an interagency all-risk incident information management system.

As of Wednesday morning, the fire had burned more than 20,000 acres and is 25 percent contained, according to MTfireinfo.org.

From the Aug. 9 fire update from Confederated Salish and Kootenai Tribes Division of Fire, four structure have been lost since the fire was initially ignited although it does not specify what type of structures.

Additionally, areas near the base of the mountains near the Big Knife fire have been placed in pre-evacuation status by the Lake County Sheriff’s Office. The same office downgraded areas near the Niarada from “evacuation” to “pre-evacuation warning.”

“A PRE-EVACUATION WARNING means you may return to your home. However, as there is still a potential threat from the Niarada Fire,” the press release states.

The Lake County Sheriff’s Office also asks people in the area to refrain from bring back evacuated livestock until the area has been downgraded to “ready.”

The Mill Pocket fire is burning to the west of the Niarada, far enough to keep both fires separated, Northern Rockies Team 3 public information officer Stefani Spencer told ICT.

“So the Mill Pocket is west, directly west of one portion of the Niarada and we have [fire] line around the Mill Pocket on the east side and the Niarada on the west side where they face each other,” Spencer said. “So we have good line around both of those fires.”

She added that the Mill Pocket is pretty well contained except for a portion on the west side near Mill Creek that is steep country and difficult to get crew to the area.

There are a number of types of personnel working the fires, including two interagency hotshot crews on the Niarada. Hotshot crews are specifically, highly trained firefighters that often take on some of the most difficult assignments.

Also, several types of aircraft have been assisting when needed. Helicopters have primarily been used to drop water but larger planes called “scoopers” and single engine planes have done the same.

Earlier this summer, fires in Canada led to air quality alerts in portions of the midwest and eastern United States. At one point, thirteen First Nations were had to be evacuated and more were on the frontlines.

The Associated Press reported erratic winds in Southern California made it difficult for firefighters to handle two major fires in the state.

On the island of Maui, six people were killed in a wildfire and injured at least two dozen others. The fire destroyed dozens of homes and businesses in Lahaina Town, a popular shopping and dining area, the AP reported.

Looking forward, weather is forecasted to be in the mid-to-high 80s with potential wind gusts up to 30 miles per hour. Spencer said they are keeping an eye on areas of the fires that will be most affected by the winds.

“Trying to get measures in place now while we have this break in the weather, and we got that rain, which really helped us out,” she said. “So we’re trying to take advantage of this break that we have in fire activity to really secure those areas that would be most affected by the wind that we’re expecting to come in.”

A stage 2 fire restriction is in place across the Flathead Indian Reservation. “No campfires are allowed, no smoking outside of vehicles, no operating combustible engines between 1PM-1PM, no operating vehicles off designated roads and trails,” a press release said.

The latest and daily information on the fires can be found on the Confederated Salish and Kootenai Tribes Division of Fire Facebook page.

The post Fires burn across Montana’s Flathead reservation appeared first on Buffalo’s Fire.

A panel of appellate judges has rejected a suite of claims brought by environmental advocates trying to halt a 220-square-mile gas field planned for a sagebrush expanse housing a famous pronghorn migration path and Wyoming’s largest-known sage grouse winter concentration area.

The developer, Jonah Energy, now has more clarity about whether to commence drilling 3,500 gas wells in the Normally Pressured Lance field, which was approved via a Bureau of Land Management environmental review seven years ago.

In its ruling, the 10th Circuit Court of Appeals affirmed what U.S. District Judge Scott Skavdahl decided a year ago: That the National Environmental Policy Act prohibits uninformed decisions, but allows for environmentally harmful decisions. In the 10th Circuit, judges Timothy Tymkovich, Nancy Moritz and Veronica Rossman quoted precedent from a 1989 U.S. Supreme Court ruling in their 31-page decision, writing that NEPA, “merely prohibits uninformed—rather than unwise—agency action.”

The statute, Tymkovich, Moritz and Rossman wrote, “does not even require agencies to promulgate environmentally friendly rules.”

That was the takeaway from a decision that denied all four claims brought by the plaintiffs: Western Watersheds Project, the Center for Biological Diversity and the Upper Green River Alliance.

“We’re disappointed in the ruling,” Western Watersheds Project Executive Director Erik Molvar said. “The judges ruled that the Bureau of Land Management was justified in not considering in great detail the impacts to the Path of the Pronghorn migration, the herd of pronghorn that summer in Grand Teton National Park. And [they ruled] it was perfectly permissible to consider impacts to pronghorn only at the broadest possible scale, the scale of the Sublette Herd.”

The dispute over pronghorn — which took center stage during oral arguments — comes at a time when the famous migration treading through the Green and Snake River basins is under siege from a host of pressures, ranging from a deadly winter that shrunk the herd by 75%, to housing developments infringing on the herd’s habitat.

The state of Wyoming recently offered a section of land in a bottleneck portion of the migration for oil and gas leasing, and it went to the high bidder, Kirkwood Oil and Gas, for $19 an acre — though that sale has been stalled. Meanwhile, the state has dragged its feet at designating the migration path, which could buffer the Path of the Pronghorn from intense drilling in places like the NPL field.

In their appeal, the environmental groups argued that the BLM violated federal environmental law by failing to take a “hard look” at how the gas field would impact the Path of the Pronghorn.

Tymkovich, Moritz and Rossman weren’t persuaded.

“The [g]roups misunderstand the regulations,” the appellate justices wrote. “They do not require the Bureau to pay special attention to special resources.”

The 10th Circuit panel found that analyzing the larger Sublette Herd was adequate. And the harm the gas field, which sits 25 miles south of Pindale, would cause was properly detailed, they wrote.

“The [environmental review] squarely confronted the ‘displacement’ and ‘disrupt[ion]’ of pronghorn ‘migration patterns’ and discussed the ‘[d]egradation’ of ‘migratory routes’ that ‘connect crucial winter range and other pronghorn habitats in the analysis area and the region,’” the opinion reads.

Other arguments brought by the plaintiffs concerned the phasing of development within the 140,000-acre gas field, and alleged NEPA violations for inadequate data gathered about impacts to Grand Teton National Park and sage grouse winter concentration areas.

The NPL gas field overlaps about half of a complex of sage grouse wintering ground that housed an estimated 2,000 birds in 2015. Highly protected sage grouse “core” habitat has also been kept out of the gas field — and it isn’t being added through an ongoing revision process, leaving birds in the project area vulnerable.

In denying the plaintiffs’ argument, the appellate judges found the BLM vetted grouse impacts adequately: “The Bureau clearly possessed enough information to anticipate how development would affect the sage grouse and [winter concentration areas] under the selected action.”

The agency’s proclamation that the gas field would cause sage grouse “various adverse effects” was enough, they wrote.

Likewise, the panel of judges didn’t buy the argument that the BLM failed to take a hard look at how the project would indirectly impact Grand Teton National Park by harming pronghorn. The judges faulted the plaintiffs for not raising those concerns when the environmental impact statement for the NPL field was being reviewed, and they pointed out the agency did acknowledge indirect interference with “recreation experiences outside the Project Area.”

Paul Ulrich, vice president of government and regulatory affairs for Jonah Energy, declined an interview for this story. It’s Jonah’s policy to not comment on litigation, he said, and there’s not a “clear picture” for the gas field moving forward.

Some activity, however, is underway — and road building and even some drilling was taking place while the project was tied up in the courts.

Records from the BLM’s Pinedale Field Office show that drilling was occurring within the project area as early as 1994. Although the agency’s record of decision for the 3,500-well project was approved in 2018 and litigated shortly thereafter, judges never put a stop to activity in the disputed field.

From the BLM, WyoFile obtained Jonah Energy’s application-to-drill documents for well pads within the field last winter. At that time, there had been 18 total submitted applications since the decision was published, 11 of which had been approved. Visits to coordinates of several of those approved pads show that, in places, the sagebrush has been scraped and ground leveled to accommodate Jonah Energy’s industrial operations.

“Where are we now with NPL?” BLM-Wyoming Deputy Director Brad Purdy said. “We are doing site-specific NEPA, which basically is going to be [applications to drill].”

Through that process, he said, stipulations are imposed that are intended to protect wildlife like sage grouse and big game and other natural resources.

If natural gas market conditions ripen, Jonah Energy has the latitude to greatly increase the pace. Wells can be constructed at a rate of up to 350 per year, with an average of 10 drill rigs working at any one time, according to the gas field’s final environmental impact statement. At the time of its approval, the gas field was expected to generate an estimated $17.8 billion over 40 years.

Although they’ve sustained successive losses in court, the project’s opponents haven’t abandoned the fight.

“There’s always the option to request an en banc review, which would involve additional judges and not just the three we happened to draw,” Western Watersheds Project’s Molvar said. “There are other options for appealing a 10th Circuit ruling, but that’s the one that I would think that would be most likely.”

Meantime, Upper Green River Alliance Director Linda Baker bemoaned what she sees as more blows to the “internationally significant gem” of the Path of the Pronghorn and the valley’s “iconic sage grouse.”

“It’s really sad,” Baker said. “And it’s tragic that the federal Bureau of Land Management and the state of Wyoming governor’s office fails to recognize what an incredibly priceless gem we have here.”

The post Court OKs 3,500 gas wells amid ‘Path of the Pronghorn,’ sage grouse winter habitat appeared first on WyoFile.

Thousands remain without power Wednesday as winds are expected to drop.

In mid-July in Phoenix, a man demonstrated to a local news station how to cook steak on the dashboard of his car. The city sweltered through a nearly monthlong streak of 110-degree temperatures this summer, while heat records are tumbling across the Southwest.

But despite the signs that this is the new normal, farmers in the region are planting the same thirsty crops on the same parched land in the desert, and watching them wither year after year. And why not? The American taxpayer is covering their losses.

Research released in June by the Environmental Working Group shows that, since 2001, heat linked to climate change has driven $1.33 billion in insurance payouts to farmers across the Southwest for crops that failed amid high temperatures. As the planet warms through the century, payments resulting from the impacts of climate change across the nation are likely to increase by as much as $3.7 billion.

Studies have repeatedly shown that federally subsidized crop insurance discourages farmers from updating their practices, tools, or strategies in ways that would help them adapt to climate change—but the federal government still subsidizes a whopping 62 percent of farmers’ insurance premiums. Until someone in Washington figures out a better way to spend our money, farmers in the Southwest are going to keep planting thirsty crops in the desert. They have little incentive not to.

Heat linked to climate change has driven $1.33 billion in insurance payouts to farmers across the Southwest for crops that failed amid high temperatures.

The Federal Crop Insurance Program (FCIP), the world’s largest crop insurance system, was established in the wake of the Dust Bowl to protect farmers from debilitating acts of God—decades before a growing body of scientific work firmly established the link between our fossil fuel use and rising temperatures. Although the government’s safety net for farmers includes an array of tools, this single program’s annual $10-billion price tag, which covers everything from drought in Arizona to flooding in Mississippi, accounts for a third of all public money spent on agriculture. Four-fifths of that are used to subsidize farmers’ costs.

Buoyed by ardent lobbying from large agricultural interests, the FCIP guarantees near-normal revenues in the face of losses that would cripple other businesses. It props up poorly managed operations while enabling risky decisions—like growing thirsty crops in a desert where millions of people vie for dwindling supplies of water.

In states like Arizona that depend on the stressed Colorado River, how and what farmers choose to grow has taken on new importance. Agriculture uses three-quarters of the region’s water to raise crops like cotton, which sucks up an average of 41 inches of irrigation annually, compared to wheat, which needs just 25 inches. Despite the arid conditions, there are plenty of reasons why farmers in the Southwest grow cotton, including the market, availability of financing, past experience, and the tools at hand. Subsidized insurance is a big one.

Although the program covers more than 100 different crops across the U.S., the vast majority of payouts go to corn, soybeans, wheat, and cotton, which are planted nationally on the most acres. Cotton is unique in the FCIP program in that it accounts for only 5 percent of the total acres enrolled in FCIP policies, but it has received a full 10 percent of claim payments over the past three decades—thanks in part to its intense water needs and the droughts that have roiled portions of the country in recent years. In central Arizona, where farmers experience the most acute impacts of Colorado River water shortages, a bale of cotton that sells for 65 cents actually costs 83 cents to raise. Still, cotton growers in Pinal County, south of Phoenix, continue planting with help from around $10 million in annual crop insurance payments—more than in any other county in the state.

Agricultural production is worth protecting; food and fiber are too important to subject to the increasingly cruel vagaries of the weather and global trade. But as it stands, the FCIP is maladapted to the challenges of our modern world, where places like Arizona are routinely smashing through heat records and water in the West is becoming increasingly scarce. While home insurers like State Farm are pulling out of California and Florida due to the mounting costs of climate disasters, the FCIP is doing the opposite: insulating farmers from the true cost of doing business.

The average return for home and auto policies is about $0.60 per dollar spent on premiums. Farmers receive an average of $2.22 for every dollar they put into crop insurance. As a result, between 2000 and 2016, farming businesses—mostly large ones—collectively pocketed $65 million more in claim payments than they paid in premiums. They were paid to plant crops that never came to market.

What is clear is that farmers’ participation in subsidized crop insurance programs is primarily driven by its availability.

Despite these failures, some of Washington’s most influential players say that the FCIP is working just fine. Collin Peterson, a 15-term Democratic Congressman from Minnesota who is now a lobbyist for the agriculture industry, said last year that the program is “the most successful thing we’ve done in agriculture.” Without federally subsidized crop insurance, he argues, farmers would be unable to compete with global markets or Mother Nature. But farmers saw prices and incomes strengthen during the years leading to 1980, before Congress expanded the program to subsidize premiums. Other supporters contend that consumers would suffer from skyrocketing prices. Yet economists have found no meaningful link between food and fiber prices and crop insurance.

What is clear is that farmers’ participation in subsidized crop insurance programs is primarily driven by its availability. When faced with paying the full cost of premiums themselves, farmers find other, cheaper means of managing risk, like conservation practices that save money in the long run, according to a recent analysis by The American Enterprise Institute.

The age of climate change demands better ways of managing risk. We need agriculture—even in Arizona. There’s good sun in the desert, and it makes sense to take advantage of that asset by planting well-suited crops. Some farmers are trying overlooked native food crops, including beans or experimental rubber plants, but these so far lack the market opportunity that the FCIP helps to maintain for cotton.

I’ve met farmers in Arizona who would gladly accept an alternative to cotton if it were economically viable. But there are other factors in play. Although the FCIP is government funded, its policies are sold and serviced by 14 private insurance companies that have gotten rich by keeping things exactly as they are.

Most of the program’s money not spent subsidizing premiums is used to reimburse these companies’ administrative costs. Ten of these are large, publicly traded corporations whose CEOs collectively take home almost $112 million a year, according to the EWG. And they all earn a 14.5 percent rate of return on their investments, compared to the 10 percent common to other insurance industries. This is thanks to the lobbying efforts of groups like the nonprofit American Farm Bureau Federation, which owns American Farm Bureau Insurance Services, Inc.—one of those 10 providers.

Lawmakers are currently negotiating a new farm bill—a once-every-five-years opportunity to set FCIP policy. Subsidies still make sense for many farmers, especially small ones, but a few updates to the program would go a long way. First, funds should be reserved for the growers most in need, not millionaire operations. Next, to adapt to climate change, forecasts for determining premiums should be based on the latest climate models, rather than historic trends. Painting a more accurate picture of the risk would inform more sustainable cropping decisions.

Most importantly, FCIP funds should be used to pay farmers to permanently retire acres that consistently fail to produce. This would allow farmers to focus their efforts and resources where they do the most good. The program should also limit its coverage of crops ill-suited to their regions, and instead invest in existing conservation programs and research into markets for desert-adapted products. A sober fix would be to reapportion some FCIP funds to existing programs that help farmers upgrade their irrigation systems, or that provide conservation and agricultural assistance—including those that help reduce on-farm greenhouse gas emissions.This is all politically difficult, but it’s not impossible—and the advancing water crisis in the West means that time is of the essence. In May, legislators celebrated the latest inadequate agreement for sharing what’s left of the Colorado River. Like the winter’s generous snowpack and spring’s encouraging rains, the deal will buy a little more time to find a sustainable solution to the region’s chronic water shortage. Meanwhile, technocrats float implausible fixes, like piping in water from the Mississippi River basin or desalting the Sea of Cortez. Congress has an opportunity to end some of this absurdity—to change the incentives to reflect the reality of a changing climate, and allow desert farmers to continue providing food and fiber while doing their share to help avoid a calamitous future.

This article was produced in collaboration with The New Republic. It may not be reproduced without express permission from FERN. If you are interested in republishing or reposting this article, please contact info@thefern.org.

A third Franklin County town signed on this week to a letter to Maine’s congressional delegation opposing a national wildlife refuge in the western Maine mountains, while a separate town abstained from a commitment.

The Wilton Board of Selectpersons unanimously approved the letter Tuesday and the Carrabassett Valley Select Board decided not to take a stance after a discussion with a federal official and an opposition member.

The two approaches — one town voicing objection, the other adopting a wait-and-see outlook — reflect broader trends by local officials, residents and recreationists in the area.

Those staunchly against the refuge have said state and local conservation efforts in the area are sufficient. They are wary of federal oversight, which they say could limit hunting and recreation access; others say it’s too soon to decide either way.

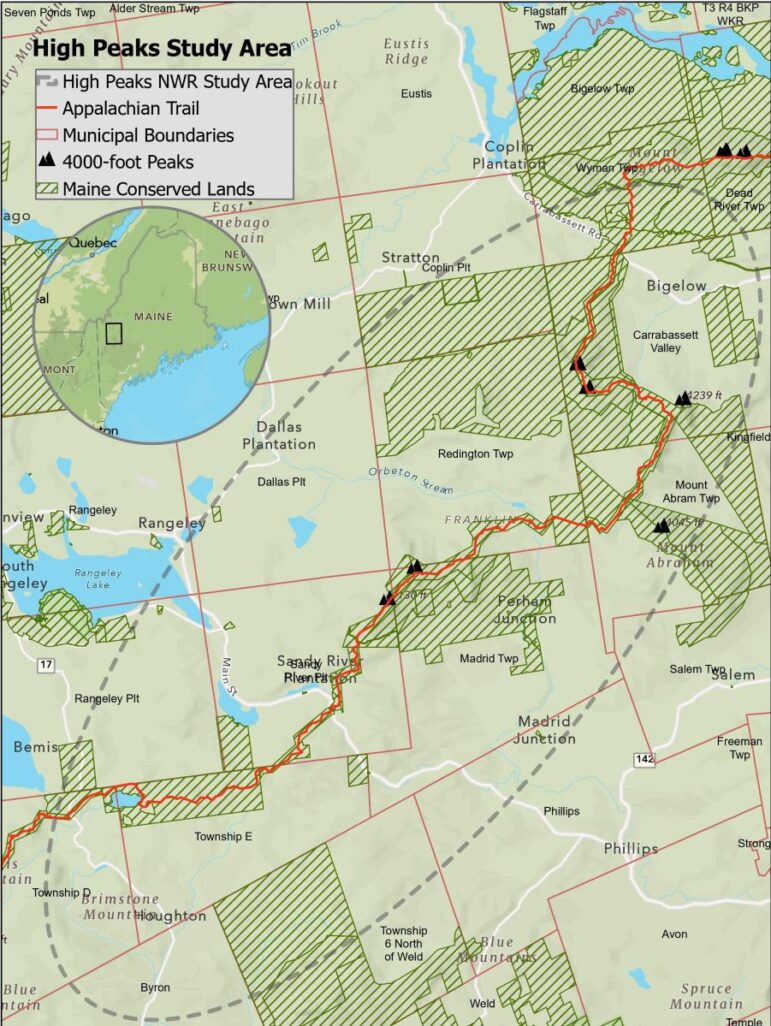

The U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service this spring began exploring the creation of a roughly 200,000-acre refuge straddling the Appalachian Trail in the High Peaks region.

Ultimately the area would likely be pared down to between 5,000 and 15,000 acres, according to Nancy Perlson, a local conservation consultant working with the Fish and Wildlife Service.

The High Peaks region encompasses some of the highest mountains in Maine and one of the state’s largest roadless expanses.

Paul Casey, a Fish and Wildlife official managing the process, has said the refuge would provide more opportunity for conservation and protection of local wildlife than the state currently offers.

Over the past few months, the agency has held a series of “scoping sessions” in Rangeley, Farmington and Carrabassett Valley to hear public input.

A formal proposal is expected by this fall and would be followed by a 45-day public comment period.

Along with Wilton, other Franklin County officials have begun voicing opposition to the proposal.

In May, the Eustis Select Board voted unanimously to oppose it and was followed in June by the Franklin County Commission, which voted 2-0-1 in opposition, with one abstention.

Both the town and county went on to sign the opposition letter, which Franklin County Commissioner Bob Carlton said was written by a coalition of citizens who oppose the refuge.

The town of Avon’s select board also signed the letter, a town official said Friday.

Carlton and Tom Saviello, a former state representative and Wilton selectperson, attended Wilton’s meeting Tuesday to lay out their arguments against the proposal and present the letter.

“We all want to protect the High Peaks, there’s no question about it,” Carlton said. “We want to keep what’s there, we want to keep it open for all the things we like to do,” like hunting, fishing, ATVing and snowmobiling.

Carlton said ATVs wouldn’t be allowed on the refuge, and certain hunting methods would be restricted — including bear hunting with bait and using lead ammunition on small birds and game.

“All of a sudden we have a piece of land … that we can do what we want and we follow the state of Maine laws and regulations,” Carlton said. “Now we’re saying, ‘Come here, but these are the rules you have to follow,’ so it’s restricted right off the bat.”

Saviello, who said he supported an earlier USFWS refuge proposal in 2013, emphasized that the current proposal would pull control from local residents and center it in Washington as opposed to Augusta.

“If there’s a problem in the refuge, with access and so forth, where do you have to go? Washington D.C.,” Saviello said. “If there’s a problem on public lands today, you go to Augusta, you go to your legislator, you have a voice that’s very strong if it’s managed by the state.”

Casey, the USFWS official managing the process, is based in New Hampshire, where he is the manager of the Umbagog National Wildlife Refuge, which includes parts of western Maine.

Selectperson Mike Wells agreed with Saviello, saying the refuge would dilute local input.

“The closer it is to home, the more of a voice we have,” Wells said.

The Carrabassett Valley Select Board took no action following a similar conversation with Carlton, as well as Casey and Perlson.

Though two select board members said they were apprehensive of the proposal, another expressed being uncomfortable with voting in opposition that night, adding that he thinks the community wants to know more, according to the Daily Bulldog.

That sentiment is reflected in a recent editorial by Will Lund, editor of The Maine Sportsman magazine.

Lund wrote in the August edition that fellow recreationists should hear out the USFWS and not jump to conclusions while the refuge proposal is in such early planning days.

“The easiest position to take on such proposals is an automatic ‘No,’ since many of us have a healthy distrust of the federal government in any form,” Lund wrote. “However, in our view it does not make sense to shut down the conversation.”

Lund went on to refute claims that the refuge would outlaw hunting, fishing, general public access and the rights of current private landowners.

In regard to snowmobile and ATV use, Lund wrote that the USFWS knows no proposal would be supported unless it called for continuation of snowmobile and other motorized travel.

He also asks outdoorspeople to consider whether private landowners will commit to public access in the future, rounding the editorial out with a contemplative approach to what the USFWS is proposing.

“To be clear, we are not supporting establishment of a refuge. How could we?” Lund wrote.

“There has been no written, detailed plan put forth that draws the boundary on a map, or that takes into consideration the input the Service has received,” and other questions need addressing, he added.

“However, it’s important to keep talking. It’s challenging to think in the long terms that are required to ensure access to land for our children and our children’s children. However, when land is developed, it’s gone forever. Let’s hear the feds out on this one.”

The story Third town opposes national wildlife refuge, another puts off a commitment appeared first on The Maine Monitor.