The Wired, Wired West: The Collapse of Public Internet in Easthampton and the Struggle to Connect Massachusetts’s Overlooked Communities

When Easthampton voters cast their ballots in 2019, there was only one contested race for city office.

But it wasn’t any of those unopposed candidates for mayor, City Council or School Committee that received the most total votes in the election. Instead, it was a ballot question asking voters to establish “a city-owned company that can provide utilities services including telecommunications systems and internet to households.” Of the 4,195 residents who voted in the election, 79% agreed they wanted Easthampton to create a municipally owned utility, which officials had begun exploring to bring city-owned broadband internet to town.

But after some five years of work toward establishing a municipal network of faster fiber optic cables to deliver broadband — including the passage of the ballot initiative, a detailed feasibility study and $150,742 in taxpayer money spent on design work for the project — Easthampton’s path toward a public utility came to an abrupt end earlier this year.

City residents are still getting fiber internet. But instead of a publicly owned utility rendering that service, a private equity-owned company called GoNetSpeed will be providing it. On May 25, the mayor’s office and GoNetSpeed announced a “partnership” to install fiber optic cables, which use light signals to transfer information more quickly and reliably than other platforms, across the city. GoNetSpeed said that it was fully funding the $3.6 million it would take to build the network citywide and may begin service as early as the start of 2024.

For some, the arrival of GoNetSpeed was a long-awaited development in a city where telecom giant Charter Communications is the only internet service provider. An advisory committee concluded in 2021 that there was “general dissatisfaction” in Easthampton with the quality and price of current internet services — issues that GoNetSpeed has promised to improve with its fiber optic cables and by providing competition to Charter.

“Through this partnership, we are able to ensure that internet connectivity is broadly available in a time when it is a necessity for our daily lives,” Easthampton Mayor Nicole LaChapelle said in that May announcement.

But for others who dreamed that a city-owned broadband utility would serve residents better than a for-profit company, the mayor’s decision to work with GoNetSpeed represents a “missed opportunity.” Several of those involved in the campaign for a public internet network in Easthampton expressed disappointment in the development, pointing to cheap and reliable municipal broadband services in neighboring communities like Westfield, South Hadley and Leverett as examples of what the city could have had.

Paul St. Pierre chaired the Easthampton Telecommunications Advisory Committee, which between 2019 and 2021 studied broadband infrastructure, market conditions in the region and what the city could do to ensure affordable and effective internet service for all. The group’s report recommended the city move forward with municipal broadband, concluding Easthampton could do so without raising property taxes.

As many as 7% of Americans don’t have adequate broadband service, according to federal estimates. In Massachusetts, census data show that 10% of the state doesn’t have access to a broadband subscription, a “digital divide” that exists in both rural and urban communities and separates those who have access to affordable, high-speed internet and those who don’t. In the Connecticut River Valley, the divide is even more pronounced; data that the state-run Massachusetts Broadband Institute recently presented at a listening session show that 28% of the 281,000 households in the region have no broadband internet subscriptions and 52% of municipalities have “little to no competition in the broadband market.”

In Easthampton, the Telecommunications Advisory Committee looked toward public ownership of city broadband as a way to address those inequities in their own community.

“It was about creating a municipal utility and kind of viewing internet service as a utility and no longer a luxury,” St. Pierre told The Shoestring. “Seeing that the private company is coming in, in a way it kind of validates what we were saying: that this is an economically feasible thing that we could have done.”

***

Nearly eight years ago, ambitious plans were moving forward to bring publicly owned broadband to some of the least-connected municipalities of western Massachusetts. But then, the project came to a screeching halt.

At the time, 40 rural towns were preparing to build out their own fiber optic network as a regionally owned cooperative, WiredWest. Then the Massachusetts Broadband Institute, under newly elected Republican Gov. Charlie Baker, suddenly pulled support from the project in favor of partnering with for-profit companies. The initiative “crashed and burned,” Berkshire Eagle investigative reporter Larry Parnass wrote in 2017, over MBI’s concerns with WiredWest’s business model — worries that the cooperative’s backers said were overstated. WiredWest still exists, but now provides services to only six member towns.

The demise of WiredWest’s initial plans, however, was far from the end of public broadband initiatives in the region, some of which have flourished in the time since. For example, western Massachusetts communities with established municipal electric utilities — known as municipal light plants — have built out their own fiber networks in recent years and worked with other municipalities to help them do the same.

Leading that charge in Hampden County is Westfield Gas & Electric’s municipal internet service Whip City Fiber, which serves some 20 municipalities across the region, from West Springfield to Wendell and including the remaining WiredWest towns.

In Hampshire County, the South Hadley Electric Light Department, or SHELD, has steadily built out its fiber network to 95% of the town and has helped both Shutesbury and Leverett build their own networks. SHELD General Manager Sean Fitzgerald told The Shoestring that although a municipal utility has to make a certain degree of revenue, it doesn’t have to operate with profits in mind like an investor-backed company. That means that public utilities’ rates tend to be lower and more stable, and their customer support more responsive, he said.

“There’s really kind of a renaissance going on with internet service providers in the United States,” Fitzgerald said. “In our region, what you’re seeing is a lot of towns, dozens of them, voting to become their own municipal light plant … The reason that’s happening is that the larger corporations aren’t investing in fiber optics in western Massachusetts.”

That is particularly true in rural communities where smaller populations are spread out across a wider geographic area, making private companies hesitant to invest because of the high costs of installation and lower customer base to recoup those costs.

Some rural communities elsewhere in New England have decided to band together to build broadband infrastructure. In Vermont, for example, 213 municipalities — representing 76% of the state’s population — had joined a “communications union district” that can issue revenue bonds to finance broadband networks as of November 2022. Maine has also witnessed the creation of two regional broadband utility districts, and last year state lawmakers there passed a bill that supports municipal broadband infrastructure.

Other municipalities in Massachusetts have considered a hybrid approach through public-private partnerships.

Last month, Northampton released a market and feasibility study of municipal broadband that it hired the firm Design Nine to conduct. (In 2021, Northampton residents voted 91.3% in favor of creating a municipal light plant.) That report suggested the city could play a key role in providing broadband infrastructure by, for example, building the fiber network and leasing it out or partnering with a private internet service provider by financing the buildout in return for guarantees the company would service all neighborhoods. The report recommended that the city not become its own internet service provider.

Elsewhere in the state, a group of 26 towns — mostly in eastern Massachusetts but including East Longmeadow, Hampden and Wilbraham — formed the Massachusetts Broadband Coalition, which has been exploring similar public-private partnerships, according to reporting from the community development-focused national nonprofit Institute for Local Self-Reliance.

Sean Gonsalves, the associate director for communications at the Institute for Local Self-Reliance’s Community Broadband Networks Initiative, told The Shoestring that efforts to build public internet infrastructure picked up momentum when the pandemic began in 2020. Many people started attending school and working from home, and some communities realized that they should be treating the internet as a fundamental municipal service, he said.

“You’re looking at it as civil infrastructure much like roads and water systems, and when a municipality bonds to build these networks … you don’t need to make a lot of money and you have a longer time to pay off those bonds,” Gonsalves said.

As part of the $1 trillion infrastructure bill that Congress passed in 2021, the federal government is now pouring $42 billion into high-speed internet infrastructure, including $147 million in Massachusetts. Later this year, the Massachusetts Broadband Institute is expected to release a plan for spending that money, which must be used first to bring broadband to entirely unserved, largely rural communities. Only after that are states allowed to spend money on communities designated as “underserved” based on the availability of higher-speed internet — money that Gonsalves said could be used to connect, for example, low-income apartment buildings.

The Massachusetts Broadband Institute has been on an “Internet for All” listening tour of the state as it puts together that plan for spending those dollars. It remains to be seen whether the bulk of those Broadband Equity, Access, and Deployment funds, as they’re known, will go to fostering publicly owned operations or private companies in Massachusetts.

Given the parameters of the program, though, BEAD money is less likely to arrive in municipalities like Easthampton and Northampton, leaving those communities looking for other ways to bring fiber to homes.

In a municipal broadband community meeting last month introducing the Northampton report, Mayor Gina-Louise Sciarra told those gathered that federal and state lawmakers have said Northampton likely would not qualify for BEAD funds. Design Nine consultant Andrew Cohill said that those challenges Northampton is facing mirror those of many other municipalities.

“It’s really unfortunate the way, particularly the federal funding, has been exclusively for unserved and in some cases underserved areas,” Cohill said. “There’s a lot of municipalities in the country that do not have adequate high-speed broadband and that is also affordable. And so the financing is a big challenge.”

***

When the COVID-19 pandemic hit, schools and businesses shuttered their doors. For Easthampton resident Jason Miranda, that meant he and his family had two parents working and two children learning at home, straining their internet connection to the brink. Others had it even worse, he said.

“People who didn’t have access to a reliable internet connection were having to go sit in their cars and sit in the parking lot of the schools to do their homework,” said Miranda, who also sat on the Easthampton Telecommunications Advisory Committee.

Miranda said that he tends to favor public ownership and control of vital services, and that the committee found that many other city residents were excited about that prospect when it came to municipal broadband. The project could have started in one neighborhood, using the revenues from that to expand the network out to cover the whole city.

As Easthampton began down the path of exploring municipal broadband, the city initially contracted with SHELD, South Hadley’s public utility, to build out its broadband network. But after SHELD finished the first phase of that work conducting a utility-pole survey and drawing up a complete city-wide design for the project, LaChapelle decided to move in a different direction.

This summer, shortly after GoNetSpeed and the mayor’s office announced that the company was coming to town, the City Council signed off on paying SHELD $150,742 out of the city’s reserve account for the work SHELD did instead of going to court over the breaking of the contract.

GoNetSpeed is a conglomeration of small, previously independent telephone companies scattered across the country, including in Maine, Massachusetts, New Hampshire and Vermont. Originally known as OTELCO, the company was publicly traded until 2021, when the private equity firm Oak Hill Capital bought the company and took it private.

In municipalities big and small alike, GoNetSpeed is pouring millions of dollars into fiber investments in Connecticut, Maine, New York and western Massachusetts, where Amherst was the first town GoNetSpeed connected to its network in July.

“GoNetspeed is working to ensure that more communities throughout Massachusetts will soon have access to a high-speed 100% fiber internet infrastructure,” the company’s press release said at the time. “In the coming months, more communities throughout the state will join Amherst in having access to GoNetspeed’s fiber internet.”

Jamie Hoare, GoNetspeed’s chief legal counsel, told The Shoestring that while he believes there are places where a “municipal solution” is appropriate to building fiber networks, private companies can save taxpayers money because cities and towns won’t have to bond to build that infrastructure.

“I think an easier way to approach the issue, where available, is to allow private providers to build their networks and to remove the barriers that exist for that,” he said.

To that end, the company is backing legislation that would speed up the process for granting applicants like GoNetSpeed and others access to utility poles. That process is currently overseen by the companies that own the pole network, and Hoare said that makes it costly and sluggish for possible competitors to obtain the efficient access they’re entitled to on those poles. Hoare said the “intransigence” of those companies is standing in GoNetSpeed’s way, not competition from municipally run networks.

(In other states, telecom giants like AT&T and Comcast have lobbied for bills that restrict or outright ban municipalities from establishing public broadband networks. The organization BroadbandNow has identified 16 states that still have those kinds of laws on the books.)

GoNetSpeed has said that in a region where a large majority of residents only have one internet service provider to choose from, the company’s arrival in Easthampton will create competition and drive down prices.

“The profit motive is what drives us to keep our prices down to attract as many customers as we can because we understand that customers do have choices in this area and, yes, what we provide is the best service,” he said.

LaChapelle said that it was ultimately her who, after crunching numbers and looking at timelines, decided to welcome GoNetSpeed instead of possibly taking on debt to support municipal internet. She said that the city has a lot of projects in the works and that she had to choose what to spend public dollars on. GoNetSpeed said it would connect the entire city to its network, and that it wouldn’t cost the city anything, so LaChapelle signed an agreement with the company.

“I really wanted to see broadband across the city and I didn’t want to have to do it in chunks,” she said. “And I didn’t want to have to commit the city to having to bond while this [municipal light plant] was getting up and running.”

Some of those who worked on bringing municipal broadband to Easthampton, however, have questioned whether a private company will benefit customers in the long term or keep its promises to build out the entire city.

“On the one hand it’s good that we have competition now, we have more than one offering,” Miranda said. “But that said, it remains to be seen the quality of the service and what kind of price they’re going to come in at and what those prices are going to look like year over year. I certainly don’t think it’s as competitive as a municipal service could have been. Or as responsible.”

In its “joint working initiative agreement” with Easthampton, which The Shoestring obtained through a public records request, GoNetSpeed agreed to “building and deploying a fiber network city-wide to homes and businesses, without installation fees for residential customers, as soon as possible.” That, however, is “subject to supply chain and/or state agency and other third parties.”

“Sure, what a corporation puts into a letter, it’s not scripture,” LaChapelle conceded. “But they’ve made good on their promises so far.”

As part of the agreement, the company will also support the city’s efforts to educate residents about the federal Affordable Connectivity Program, which provides up to a $30 monthly discount on internet service for households at or below 200% of federal poverty guidelines. (On Tuesday, LaChapelle’s office also announced that the Massachusetts Broadband Institute had selected Easthampton to be in the first cohort of communities it will help develop a “digital equity plan” that will “outline a path for closing the digital divide.” The city and its consultants will hold a listening session of their own on Oct. 25 at 6 p.m. at Mountain View School.)

Gonsalves, the broadband expert at the Institute for Local Self-Reliance, said that he isn’t familiar with the specifics of Easthampton’s situation. But speaking generally, he said that private-public partnerships work best when communities are investing capital into the project too, allowing them a real seat at the table. When a municipality just plays “a support role,” he said it is very difficult, if not impossible, to have any say.

“Generally speaking, the more skin in the game that a community has, the more say they have in terms of the outcome: timeline, affordability, reliability standards,” he said. “Those are the kinds of things that can be part of a private-public partnership and can be negotiated.”

Others have expressed concern about the possibility that GoNetSpeed gets gobbled up by a bigger competitor at some point in the future.

Private equity firms invest large pools of money — from wealthy people or endowments, for example. Often, a strategy they use to make handsome returns on those investments is by buying companies, restructuring them and selling them at a higher price.

Before Oak Hill Capital bought OTELCO in 2021, the company was publicly traded and, for that reason, had to make regular disclosures to the U.S. Securities and Exchange Commission. In one filing OTELCO made to the SEC in 2019, the company pointed to Oak Hill Capital’s role in gobbling up the competition in New England.

“Consolidation in the telecom sector over the past few years has significantly shrunk the universe of Otelco’s competitors, especially in the Northeast, with the completed acquisitions of Firstlight, Oxford Networks and Sovernet by Oak Hill Capital,” the report said.

The report said that one of OTELCO’s “operational objectives” was the expansion of its fiber network, increasing revenue per customer and making the company “more attractive for targeted acquisition.”

That’s exactly what happened in 2021, when Oak Hill Capital bought the company and took it private. Now, some have expressed worries that one of the telecom giants will purchase GoNetSpeed after it builds out more of its fiber networks.

“There’s no control in the long term,” Miranda said. “It does concern me, especially since private equity is involved and when they can’t get their money back they break it up and sell the parts or it just goes away.”

Hoare, the GoNetSpeed lawyer, said that it doesn’t seem like Oak Hill Capital has plans to seek a buyer and that the company plans to stay in the region.

“It’s difficult to think about what does the future hold, but we’re not looking to join up with other companies in the area,” he said.

***

A thin blanket of fog lay draped across Easthampton last Thursday morning as workers in reflective, neon coats moved down South Street in bucket trucks. At one end of the street sat a large spool of thick fiber-optic cables, spinning slowly as workers let out the line and hung it from one utility pole to the next.

When St. Pierre learned that Easthampton had jettisoned plans for municipal fiber and that GoNetSpeed was beginning work in the city, he said it was bittersweet. The city probably could have done it better, he said, but GoNetSpeed’s arrival will mean more competition.

“I hope they’re able to deliver a quality service that would serve the people of Easthampton effectively,” St. Pierre said. And while he’s not familiar with GoNetSpeed, he said the bar is low for them. “It would be hard for them to do worse than Charter. They’d have to really try.”

Others involved with the Easthampton Telecommunications Advisory Committee described the development as a disappointment. Miranda said that when the committee handed in their report, he never heard about it again from city officials.

“We never got a follow-up, we never got invited to the City Council meeting when they discussed it,” Miranda said. It was the first time he got involved in a city committee, and he said the lack of communication has made him leery about participating in something like that again. “I think our job was done, but at the same time, it’s sort of like all the work we had done just went into a black hole.”

LaChapelle said that she isn’t under any illusions that GoNetSpeed is “the friendliest corporation in the world;” they’re not, she said. The company didn’t need Easthampton’s permission to begin the work of building its own network in town, though LaChapelle said GoNetSpeed likely wouldn’t have entered the market — which Hoare, the company’s lawyer, described as “attractive” — if a municipal utility were there to compete for customers.

“Is it disappointing that we won’t have our own broadband? Yes,” LaChapelle said. “But also, going forward and staying with a private company, I feel like the city in 10 years, in 20 years, will be more on top of technology with GoNetSpeet than with [a municipal light plant] that has to continually upgrade and improve lines in the city.”

St. Pierre said that he sympathizes with City Hall, given the administration’s long list of projects now in the works to improve quality of life in the city.

“Unfortunately, the municipality, for whichever reason, was not able to move forward and the private company saw the opportunity and jumped on it,” he said. “Even though we could have done it on a municipal level if we had moved a little faster.”

City Councilor Tom Peake was perhaps the biggest proponent of municipal broadband, moving the project through two City Council votes in order to get the question on the ballot asking residents if they wanted to create a municipal light plant. Peake declined an on-the-record interview about LaChapelle’s decision. In a statement, he said that it came down to the mayor and her team deciding to head in a different direction.

“I was opposed to the decision, but I understand why she made it,” Peake said. “This network will get built out, and it won’t cost the city anything. We also won’t own it or gain any of the benefits of owning it, which to me is a huge missed opportunity. On the other hand, it will allegedly be built much faster than the timeline we had for financing and building a municipal network.”

“Tough call either way,” he added.

Dusty Christensen is an independent investigative reporter based in western Massachusetts. He can be reached at dusty.christensen@protonmail.com. Follow him on Twitter: @dustyc123.

The Shoestring is committed to bringing you ad-free content. We rely on readers to support our work! You can support independent news for Western Mass by visiting our Donate page.

Massachusetts seeks to streamline approvals for community choice aggregation

Massachusetts officials are proposing policy solutions to address a bureaucratic backlog that municipal leaders and clean energy advocates say is bogging down one of the state’s most successful drivers of clean electricity purchases.

Nineteen communities across the state are waiting for public utility regulators to rule on proposed community choice aggregation plans, in which local governments negotiate with power suppliers for lower prices or a higher share of renewables.

Some of these municipalities have been waiting for more than two years to launch their programs. Another 16 are waiting to see if the state will let them modify existing programs. As the proposals languish, municipalities are missing out on chances to save residents money and cut carbon emissions.

In response to this backlog, the state energy department has proposed a new system to streamline the process, though many advocates are highly skeptical of these guidelines.

“I’m not sure that the way they’ve drafted them is really going to address the backlog,” said Martha Grover, sustainability manager for the city of Melrose, which first adopted community choice aggregation in 2015 and has held off updating the program in recent years because of the delays.

In addition, state Rep. Tommy Vitolo has introduced a bill that would require faster response times and allow municipalities to make some changes to programs without seeking state approval.

Massachusetts was the first state to introduce these programs, as a part of electricity restructuring legislation passed in 1997. The policy allows individual cities and towns or groups of municipalities to use the promise of a built-in customer base to negotiate with power suppliers for prices. Generally, residents are automatically enrolled but can opt out at any time.

The Cape Light Compact, a group of 21 towns on Cape Cod and Martha’s Vineyard, formed the state’s first aggregation program in 2000. The idea was slow to catch on, however, until electricity prices started rising in 2013 and 2014, prompting more municipalities to seek alternatives. Today, there are 168 municipal aggregation plans active in the state, saving consumers more than $200 million annually, according to a report from the nonprofit Green Energy Consumers Alliance.

Though not explicitly an emissions reduction program, aggregation also allows municipalities to include more renewable energy in their portfolios than legally required. And many of them do exactly that: 76 of Massachusetts’ aggregation programs included extra renewable content in 2022, according to the consumers alliance. Another 40 communities let individual residents opt-in to higher levels of renewable energy. In 2022, Massachusetts’ green energy aggregation programs increased demand for renewable energy in the state by more than 1 million megawatt-hours, the Green Energy Consumers Alliance calculated.

“There is no other program in the commonwealth that produces cleaner electrons without subsidy,” said alliance executive director Larry Chretien.

The delays were first caused by the COVID-19 pandemic, according to a statement from the state energy department. Additionally, the complexity of the rules and requirements for a successful application have also slowed things down, state officials and municipal leaders agree. Each time regulators rule on a plan, any new precedent set by that ruling must be complied with by all future applicants. This requirement makes it hard for municipalities to understand the rules and forces frequent revisions. It also makes it more painstaking for the state to ensure a proposal meets the ever-changing slate of requirements.

“There are now 168 approved plans and we are held accountable to rules and ways of operating that are buried in the footnotes,” Grover said.

The proposed solutions

The state has responded to the backlog by releasing draft guidelines that summarize and simplify the detailed requirements. It has also issued an application template and proposed an expedited approval process for municipalities that use the template.

“Addressing these delays is a top priority for the [Department of Public Utilities], and we look forward to announcing finalized guidelines that will help facilitate a timely review of applications,” said department chair Jamie Van Nostrand.

For many municipalities, however, the guidelines make no changes to the process, but only formalize the existing approach, which many say amounts to micromanagement. At least eight cities and towns have filed testimony so far arguing that the proposal erodes local control and would be unlikely to speed up approvals. The draft guidelines would make the process “more burdensome and less efficient,” testified Michael Ossing, city council president in Marlborough, which adopted community choice aggregation in 2006, saving residents an estimated $26 million over the past 17 years.

“Aggregation should be under municipal control,” said Anthony Rinaldi, an Amesbury city councilor. “We should control how we implement the program, how we inform our citizens. But they want to control every little thing.”

Vitolo’s bill offers an alternative approach. It would address the delays by requiring the state to issue a decision on aggregation applications within 90 days. If this deadline is not met, a program would automatically be approved. If regulators rejected a program, and applicants resubmitted an amended plan within 30 days, the state would then have 30 days to issue a decision.

The bill would also allow cities and towns to make certain changes — including periodic changes to prices and product offerings, means of providing notifications to customers, and sharing translated materials — to their programs without returning to utility regulators for approval. Vitolo points to Boston, which launched a community choice program in 2021, as an example: the city wants to distribute translations of its information materials, but can’t do so without getting in the slow-moving line for approval.

“It’s been frustrating,” Vitolo said. “We want to allow these aggregators to make simple straightforward changes without going to the [state].”

Vitolo’s bill had a committee hearing in late September. Now supporters must wait to see if it gains traction in the legislature.

Massachusetts seeks to streamline approvals for community choice aggregation is an article from Energy News Network, a nonprofit news service covering the clean energy transition. If you would like to support us please make a donation.

In Photos: This small Midwestern town still crowns its Coal Queen

Every year in August, the small town of Marissa, Illinois, celebrates the fossil fuel that gave it prosperity: coal. The area around the town, which sits about 40 miles southeast of St. Louis, used to be known for its number of coal mines, and Marissa was considered its capital.

The celebration, known colloquially as Marissa Coal Fest, is a weekend of carnival-like festivities. This year’s, held from August 11 to 13, included a meet-the-miner event, food stands, and a parade featuring the candidates for the coal court who were vying for the titles of Coal Princess, Coal Prince, and the Queen of Coal.

Virginia Harold

Despite there only being a few actual coal mines left in the area, coal is sacred here. An underground coal mine and power plant still employs a number of people in town and is a source of pride. Prairie State Energy Campus was built during the last wave of coal-fired power plants in the early 2010s, and still employs hundreds of people.

[Read more about how Midwest communities are grappling with the end of coal culture]

Though Beverly Terveer was not born in Marissa, and lives in nearby St. Libory, she finds the Marissa community welcoming and friendly. She said that folks around town are the type of people to help each other out after a disaster hits. “It’s a very warm, tight-knit community, but it also has had a big decline because of the coal industry,” said Terveer.

Despite the fact that Terveer’s house is fitted with a solar panel, a passion project of her late husband’s, she is skeptical of using farmland for renewable energy.

“I think we still need to keep the electric power grids going with coal,” she said. She attends the coal festival every year and loves to see the town come together.

Virginia Harold

Scenes from the 2023 Marissa Coal Festival parade. Virginia Harold

Virginia Harold

Beverly Terveer was one of the many locals watching the Coal Festival parade. Virginia Harold

Virginia Harold

Most people in town are fiercely protective of coal, and Marissa’s history with commercial coal mining stretches back to the 1850s. Generations of Marissa residents were employed by coal companies — often mom-and-pop operations, unlike the large corporations that dominate the fossil fuel energy sector today.

For resident Paul Weilmuenster, who was watching the parade from the front porch of his home on Main Street, becoming a coal miner was a no-brainer.

He started young, at 20, following the career path of his father, who was also a miner. He relished carrying on the tradition. Now, though, he sees how the decline of the industry has meant less investment in the town, a place he’s lived his whole life.

“Who wants to build a new home, a $300,000 to $400,000 home in Marissa?” said Weilmuenster.

Still, he’s hoping Prairie State can stay open as long as possible to keep employing local people.

“So that could be another [400 to 500] people in Marissa losing their jobs — and then what are they going to do?”

Virginia Harold

A man from the Banana Bike Brigade rides a bicycle with an attached paper-mache lion’s head during the parade. Virginia Harold

Virginia Harold

Paul Weilmuenster, a former coal miner, watches the parade from his porch with Roy Dean Dickey, a Marissa Village board trustee. Virginia Harold

Virginia Harold

Although the power plant has served as a huge economic driver for the town, not every Marissa resident has a positive experience with coal. Maria Cathcart is the daughter of a coal miner, but she said that climate change means coal needs to be phased out to prevent further warming from fossil fuel emissions.

“I see how we’re cutting back on coal, so it is cutting back on, kind of, a tradition, but it needs to be done,” Cathcart said. “We’re tearing apart our world. And we need to stop, because it’s going to get to a point where it’s going to be irreversible.”

The personal impact of coal on miners’ families was real for her. She remembers her father fondly, but also knows that the career he committed his life to contributed to his death from black lung.

“He actually died in my arms, so it really hurt me,” she said. “I was right there when he died.”

Still, she comes every year to the coal festival with her mother, Carmen. Not doing so is out of the question, even though Cathcart’s relationship to coal and the town itself remains complicated. Life in Marissa revolves around the event, and Cathcart cheered in the crowd when the parade started, alongside everyone else.

Virginia Harold

Locals set up chairs to watch the parade. Virginia Harold

Virginia Harold

Virginia Harold

Coal Queen candidates participate in the parade. Later, they will compete for the title. Virginia Harold

The Coal Festival includes food, rides, and games as part of the weekend-long celebration. And, as the carnival roars in the background and the sun begins to set, the festivities culminate in the annual crowning of a Coal Prince, Coal Princess, and Coal Queen.

Virginia Harold

Scenes from the carnival grounds. Virginia Harold

MacKenzie Jetton, a local high school graduate, was named 2023 Coal Queen. Virginia Harold

Photography by Virginia Harold

This story was originally published by Grist with the headline In Photos: This small Midwestern town still crowns its Coal Queen on Oct 4, 2023.

How does climate change threaten your neighborhood? A new map has the details.

If you’ve been wondering what climate change means for your neighborhood, you’re in luck. The most detailed interactive map yet of the United States’ vulnerability to dangers such as fire, flooding, and pollution was released on Monday by the Environmental Defense Fund and Texas A&M University.

The fine-grained analysis spans more than 70,000 census tracts, which roughly resemble neighborhoods, mapping out environmental risks alongside factors that make it harder for people to deal with hazards. Clicking on a report for a census tract yields details on heat, wildfire smoke, and drought, in addition to what drives vulnerability to extreme weather, such as income levels and access to health care and transportation.

The “Climate Vulnerability Index” tool is intended to help communities secure funding from the bipartisan infrastructure law and the Inflation Reduction Act, the landmark climate law President Joe Biden signed last summer. An executive order from Biden’s early months in office promised that “disadvantaged communities” would receive at least 40 percent of the federal investments in climate and clean energy programs. As a result of the infrastructure law signed in 2021, more than $1 billion has gone toward replacing lead pipes and more than $2 billion has been spent on updating the electric grid to be more reliable.

“The Biden Administration has made a historic level of funding available to build toward climate justice and equity, but the right investments need to flow to the right places for the biggest impact,” Grace Tee Lewis, a health scientist at the Environmental Defense Fund, said in a statement.

According to the data, all 10 of the country’s most vulnerable counties are in the South, many along the Gulf Coast, where there are high rates of poverty and health problems. Half are in Louisiana, which faces dangers from flooding, hurricanes, and industrial pollution. St. John the Baptist Parish, just up the Mississippi River from New Orleans, ranks as the most vulnerable county, a result of costly floods, poor child and maternal health, a list of toxic air pollutants, and the highest rate of disaster-related deaths in Louisiana.

“We know that our community is not prepared at all for emergencies, the federal government is not prepared, the local parish is not prepared,” Jo Banner, a community activist in St. John the Baptist, told Capital B News.

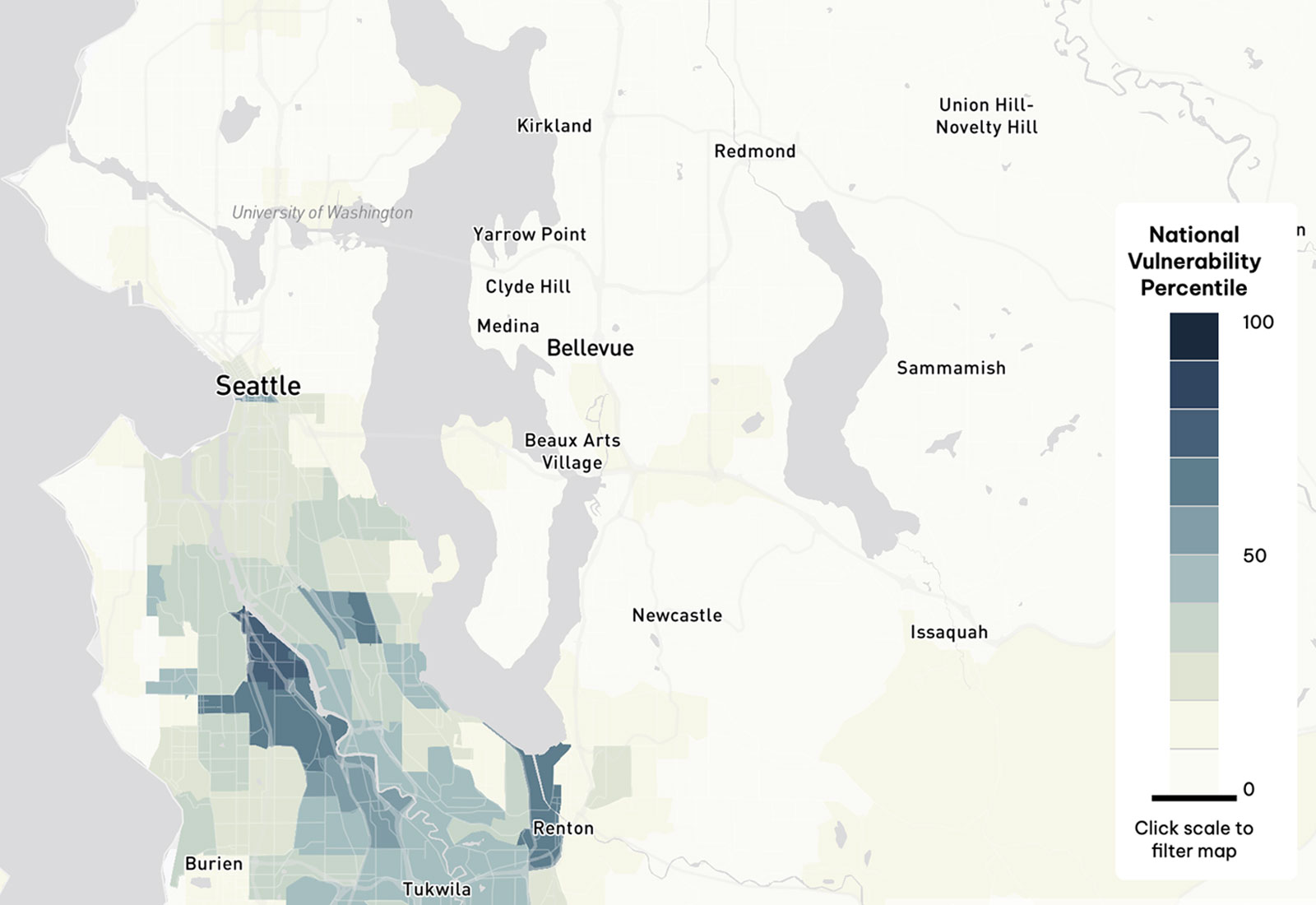

Even in cities where climate risk is comparatively low, like Seattle, the data shows a sharp divide. North Seattle is relatively insulated from environmental dangers, whereas South Seattle — home to a more racially diverse population, the result of a history of housing covenants that excluded people on the basis of race or ethnicity — suffers from air pollution, flood risk, and poorer infrastructure.

The U.S. Climate Vulnerability Index; Mapbox / OpenStreetMap

Similar maps of local climate impacts have been released before, including by the Environmental Protection Agency and the White House Council on Environmental Quality, but the new tool is considered the most comprehensive assessment to date. While it includes Alaska and Hawai‘i, it doesn’t cover U.S. territories like Puerto Rico or Guam. The map is available here, and tutorials on how to use the tool, for general interest or for community advocates, are here.

This story was originally published by Grist with the headline How does climate change threaten your neighborhood? A new map has the details. on Oct 2, 2023.

Study Looks at Climate Change Effects On Rural Electrical Grids

Researchers from across the country are studying how to improve electrical grids across the country with a focus on underserved, rural communities.

Through a four-year, $750,000 grant from the National Science Foundation, South Dakota State University, University of Maine, University of Alaska Fairbanks, and University of Puerto Rico Mayague will examine how climate change affects electrical grids. The project is titled “STORM: Data-Driven Approaches for Secure Electric Grids in Communities Disproportionately Impacted by Climate Change.”

“The basic idea is to go to a few specific communities, and through community engagement, figure out what are the challenges that they are facing with regard to the impact of extreme weather on the power grid, and then solve some of those issues in terms of community outreach and engagement, designing new methods to make the grid more resilient,” said Tim Hansen, associate professor in SDSU’s Department of Electrical Engineering and Computer Science and co-principal investigator on the project.

Hansen said the research project is based in strategic locations in which different weather events occur. Alaska, for example, deals with extreme cold, while Puerto Rico deals with storms and flooding.

The common issue is that all the events impact the power grid, he said. “Our focus is on power grid resiliency from different perspectives.”

As part of the project, the researchers will work with community members on engagement. Hansen told the Daily Yonder it will be a ground-up approach so see what the community is willing to adopt.

Daisy Huang is an associate professor at the University of Alaska Fairbanks and mechanical engineer. She also conducts research at the Alaska Center for Energy and Power, which looks at optimizing power, mostly in rural communities around Alaska. She said the rural communities are mostly not connected to the state grid.

“So they’re all on their own diesel fired power plants. And so we look at ways to integrate renewables [and] optimize their diesel for maximum efficiency,” she told the Daily Yonder.

Huang said she is also interested in creating educational programs around STEM.

“The idea is looking from a community perspective – what their energy needs are, and how we can translate that – in parallel – developing educational programs around kids learning about energy systems, [like] engineering or STEM in general, math, physics.”

There will also be a virtual reality lab for remote power and energy research studies between all the participating institutions, Hansen told the Yonder.

He said that many of the researchers on the project are young investigators. “It’s a very good opportunity for the [National Science Foundation] to really build up the mentorship, and really build a lot of people’s long-term careers off of the back of this,” he added.

The post Study Looks at Climate Change Effects On Rural Electrical Grids appeared first on The Daily Yonder.

BLM’s new management plan balances conservation, energy extraction

As an energy rich state, Wyoming is no stranger to trying to find the balance between extraction and conservation. In the case of the Greater Little Mountain area near Flaming Gorge, the attempt to strike that balance has taken over a decade, resulting in a recently released draft plan that embraces two of the state’s key economic drivers: the oil and gas industry and our great outdoors.

Opinion

This magical high desert region of over 500,000 acres in Sweetwater County boasts habitat of badlands, aspen groves and pine forests. This place, simultaneously rugged and fragile, is one of Wyoming’s most sought-after hunting grounds for mule deer and elk and holds intimate streams that shelter genetically pure Colorado River cutthroat trout. Since 1990, this area has also benefited from more than $10 million to enhance and maintain these resources from government agencies, as well as non-profits, local businesses and community members.

Last month, the Bureau of Land Management Rock Spring Field Office released a draft land use plan for southwest Wyoming that seeks to strike a common-sense balance between allowing for energy development and protecting sensitive fish and wildlife habitats.

What I appreciate most in the BLM’s balanced, thoughtful approach is how it does not impact existing oil and gas leases. In fact, over half of the planning area is already leased and there are already active, producing wells across the landscape. Simultaneously, the BLM’s newly proposed oil and gas rule would be a long-overdue win for local communities by reducing conflict between leasing and drilling and other uses that are essential to supporting Wyoming’s way of life: fishing, hunting, recreation and conservation.

For decades, the federal oil and gas leasing programs prioritized resource extraction over valuable fish and wildlife habitats on our shared public lands. This is why Congress had to pass legislation in 2009 to protect 1.2 million acres in the Wyoming Range from ill-advised oil and gas leasing. But now the BLM is working to improve public land management by curtailing speculative leasing that directly impacts wildlife habitat while providing little if any public benefit.

Public lands oil and gas development has no doubt benefited Wyoming and our country, and will continue to do so for years to come. But what’s important moving forward is continuing to find a balance between our economy and special places like Greater Little Mountain.

As Wyoming sportsmen and sportswomen begin to ramp up for hunting season — with many pursuing game in the landscapes where they work — I appreciate that the BLM’s proposed management plan for southwest Wyoming seeks to provide for both responsible energy development and conservation.

Throughout the fall, the BLM will be taking public comment on the four proposed alternative plans, and now is the time for those who care about the future of public land hunting and fishing in southwest Wyoming to speak up. Energy development and conservation need not be mutually exclusive, but it takes smart planning to strike this balance. This is our moment to get it right.

The post BLM’s new management plan balances conservation, energy extraction appeared first on WyoFile.

This Hawaii Super PAC Says It’s Raising Money For Wildfire Victims — And Political Candidates Too

Money raised for direct relief could end up being used for political candidates and activities.

Central Valley communities of color lack flood control. Would representation on water boards help?

During three weeks in December and January, storms dumped 32 trillion gallons of rain and snow on California. With it came unwelcome floods for many communities of color.

The winter and spring storms were a rare chance for drought-stricken communities to collect rainwater, rather than have their farms, homes and more overwhelmed by water. Much of the rain that fell instead overflowed in lakes and streams, leading to disaster in low-income Central Valley towns like Allensworth and Planada.

“It’s a long history of disinvestment in disadvantaged communities and communities of color, in drinking infrastructure, water systems and flood control,” said Michael Claiborne, an attorney for the Leadership Counsel for Justice and Accountability, an environmental justice organization based in the San Joaquin and East Coachella Valleys.

In the aftermath of the damage, community leaders are reiterating a call to diversify water boards to give marginalized groups more power.

The California State Water Resources Control Board, which oversees the distribution of water in the state, has acknowledged that its workforce does not reflect California’s racial composition. Part of the State Water Board are nine Regional Water Quality Control Boards. These regional boards develop “basin plans” to manage water quality in their area, taking into account their region’s unique environmental factors.

In 2020, 69% of water board management was white, while 31% were Black, Indigenous or other people of color. By comparison, 37% of California’s population is white and 63% are Black, Indigenous or other people of color, according to the 2019 American Community Survey.

“More local representation would ensure that when decisions are made, the needs of the communities impacted aren’t ignored,” Claiborne said.

The communities that flooded don’t have proper infrastructure such as levees and canals, experts said, which divert water to floodplains or groundwater basins that wells can draw from for later use.

Members of the State Water Board were not available to comment on representation by the time of publishing.

The State Water Board adopted a plan this January to improve racial equity and better represent California’s diversity. This resolution also applied to the regional boards, which used the resolution as a guide to develop their own racial equity plans.

“A lot of these board seats go uncontested,” said Allison Harvey Turner, CEO of the Water Foundation. “The same people have been in these decision-making positions for decades.”

Inequality still remains a concern when it comes to California’s water infrastructure, the first defense against floods.

Allensworth, a small farming community of mostly Latinos in the San Joaquin Valley, was ordered evacuated because of flooding from this year’s storms. The town sits at the edge of the Tulare Lake basin, which was the source of much of the flooding. Drained and cultivated decades ago, Tulare Lake was revived by the storms in less than three weeks. But its resurrection submerged miles of valuable Allensworth farmland.

Other cities near Tulare Lake, including Corcoran and Alpaugh, also suffered devastating flood damage. What were once roads, homes and farmland ended up at the bottom of almost 170 square miles of water.

While many agencies manage water, Claiborne said those bodies are dominated by wealthier, “bigger water users.”

“Disadvantaged communities have very little ability to influence local decision-making,” Claiborne said.

The central coast town of Pajaro and Merced County’s Planada are two other low-income, farming communities of color destroyed by floods. In both towns, county officials were blamed for not properly maintaining the levees that failed.

“In places that have gotten a fair amount of tension like Pajaro, levees needed work, but the investments made to shore them up failed and communities flooded,” said Harvey Turner, of the Water Foundation.

Efforts are underway to improve representation on water boards, which would give small landowners and communities of color an avenue to advocate for better water infrastructure. The Water Foundation provides grants to support organizations such as the Leadership Counsel, which helps local advocates learn about their regional water boards and run for those positions.

One current Tulare County Supervisor, Eddie Valero, is an outcome of those programs.

“That can be super powerful – if we are able to shift the faces and communities that are reflected in these water positions,” Harvey Turner said.

Bella Kim is a reporter with JCal, a collaboration between The Asian American Journalists Association and CalMatters to immerse high school students in California’s news industry.

The post Central Valley communities of color lack flood control. Would representation on water boards help? appeared first on Fresnoland.

West Maui May Reopen To Tourism On Oct. 8 As Economic Slowdown Predicted

The Hawaii governor also plans to distribute $1,200 to each adult affected by the Lahaina blaze.