Grant Helps Cape Cod Restaurants Drop Plastic

Grant Focuses on single-use plastics used in the food and hospitality industries.

Local environmental conservation non-profit

received a nearly

$300,000 Woods Hole Oceanographic Institution (WHOI) Sea Grant

from the

National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration

to help the Cape’s food and hospitality businesses move away from single-use containers and service-ware.

What is CARE for the Cape and Islands?

was founded in 2012 as the Cape and Islands’ first

travelers’ philanthropy initiative

.

More commonly known today as Impact Travel, CARE seeks to encourage, support, and create opportunities for visitors and residents to donate their “time, talent, and treasure” to help preserve and protect the region’s natural beauty, plant and wildlife habitats as well as Cape & Islands culture and history.

What is the WHOI?

Woods Hole Oceanographic Institution

is the world’s leading, independent non-profit organization dedicated to ocean research, exploration, and education.

WHOI maintains unparalleled depth and breadth of expertise across a range of oceanographic research areas.

Institution scientists and engineers work collaboratively within and across

to advance knowledge of the global ocean and its fundamental importance to other planetary systems. At the same time, they also train future generations of ocean scientists and address problems that have a direct impact in efforts to understand and manage critical marine resources.

The little-known Nevada company making millions off the western water shortage

This story is published in partnership with the Reno Gazette-Journal, with support by The Water Desk, an independent journalism initiative based at the University of Colorado Boulder’s Center for Environmental Journalism.

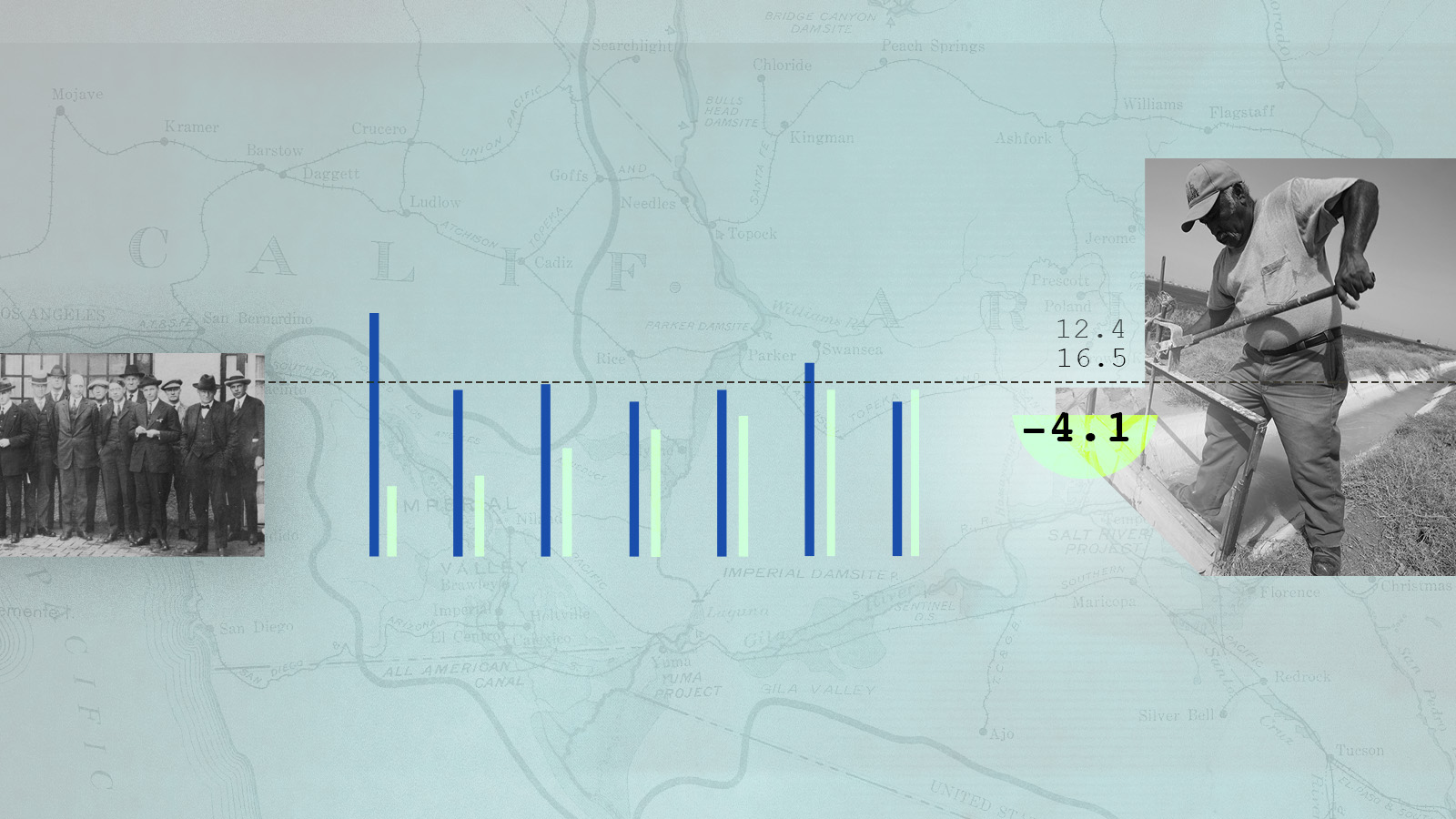

For the first two decades of the 21st century, not even a once-in-a-millennium drought could deter real estate developers from building vast suburban tracts on the wild edges of Western U.S. cities. But in 2021, a reckoning appeared on the horizon. The Colorado River sank to historic lows, winter rains never arrived, and communities from California to Texas found their groundwater wells going dry after decades of overuse.

Western officials had seldom let questions about water availability get in the way of population growth, but suddenly they seemed to have no other choice. Faced with an unprecedented shortage, many local governments tried to pump the brakes on new developments. A small town in Utah halted all new housing permits, fearful that more homes would sap a local river. A suburb of Colorado Springs, Colorado, told developers that it could no longer allow new subdivisions to connect to the city’s water system. Most significantly, the state of Arizona has all but paused new housing in some Phoenix suburbs, citing a shortage of groundwater.

This pivot to conservation was bad news for D.R. Horton, the nation’s largest homebuilding company. Buoyed by pandemic-induced demand for cheap, spacious housing across the West, Horton netted $6 billion constructing more than 80,000 homes last year alone. The company had long been able to assume that if it built a development, someone else would provide water for it — usually a local government eager for tax revenue. All of a sudden, Horton had to find the water itself.

Luckily, there was a third party who could help.

In April of last year, Horton acquired Vidler Water Company, a tiny outfit whose dozen employees worked out of an unassuming faux-Mediterranean office park in Carson City, Nevada. Though Vidler’s annual revenue was less than a tenth of a percent of Horton’s, the real estate titan spent big to snap it up: The price tag on the acquisition was an eye-popping $291 million.

Vidler is an unusual company. It doesn’t actually deliver water to people, nor does it own any facilities for water treatment or desalination. Instead the company functions as a broker for water rights, finding untapped water in rural communities and marketing it to developers and corporations in fast-growing cities and suburbs. For 20 years, the company has bought up remote farmland and drilled wells in bone-dry valleys to amass an enormous private water portfolio, then made tens of millions of dollars by selling that portfolio one piece at a time.

This kind of business inevitably involves some guesswork, and often that guesswork looks like classic real estate speculation: You can make money by bringing water to places where people already want it, but you can make even more money bringing it to places where people will want it in the future. This is exactly what Vidler has tried to do, and it has led the company’s critics to contend that its business model violates the anti-speculation spirit of Western water law.

Indeed, suspicions that Vidler is profiteering off a vulnerable public resource have made the company more than its share of enemies over the years: Top officials have been pilloried in courtrooms and threatened by rural residents, and an early executive once had to jump out a window to escape an angry crowd at a public meeting.

Horton’s purchase of Vidler has no real precedent, but it is a clear indication of where the West is headed. The region has grown twice as fast as the rest of the United States since the 1950s, and national builders like Horton are relying on it to fuel future profits. If these companies want to capitalize on migration to the booming suburbs of Phoenix and Las Vegas, they’ll need to find creative new water supplies that will allow them to keep building even as regulators try to clamp down on unsustainable growth.

Grist / Mikayla Whitmore

In this regard, Vidler is a pioneer. The company was the first in the West to make a business model out of finding and flipping water. In the past few years, a new crop of upstarts has sought to mimic this model, buying up water rights in rural areas and marketing them to developers and suburbs that need them for future growth. These companies include Water Asset Management, which has bought up agricultural land in Colorado to secure water rights, and the investment firm Greenstone, which organized a first-of-its-kind deal to move Colorado River water from farms in western Arizona to a city near Phoenix. Both companies boast former Vidler executives in top leadership positions.

Vidler still stands at the front of the pack, tapping water in hard-to-reach aquifers and pursuing aggressive litigation to push new construction forward. If the company’s tactics become more common, the effects will be far-reaching — not only could rural areas and desert ecosystems see their precious water siphoned off, but thousands of people will buy and occupy homes fed by water sources that may turn out to be unreliable. A major part of Vidler’s strategy has been to pump water from small underground aquifers, squeezing every available drop from finite water banks that may someday run dry, especially as climate change contributes to the long-term aridification of the West.

Kevin Brown is the manager of a water utility in the southern Nevada city of Mesquite, where Vidler has been trying for years to build a pipeline that could bring new water to the city. The company has proposed tapping a virgin aquifer and using the water to supply new housing developments on the edge of town, but Brown doubts the pipeline is a good idea. Instead he has focused on reducing water usage across the city and recycling water where he can.

Grist / Mikayla Whitmore

“In the world we live in, and the market we live in, if you put enough money against it, someone will make it happen,” Brown told Grist. “If these developers aren’t building homes, then they’re going out of business. But at some point, somebody needs to say, ‘You know what, we can’t grow anymore. It’s not sustainable.’”

In most Western states, water is public property regardless of whose land it flows through or sits under. Private entities can only own the right to use that water for a specific purpose. Individuals and companies can apply to use any unclaimed water source, but they have to convince the state government that they plan to put the water to a productive use. By the same token, owners can sell or lease their existing water rights to each other as long as the buyers keep using the water for something.

Grist / Mikayla Whitmore

In this arrangement, the new breed of water brokers has found an opportunity to accumulate assets and generate profits. But the law requires them to tread cautiously.

At the turn of the 20th century, a Transcontinental Mining executive named Rees Vidler tried to dig a tunnel through the heart of the Colorado Rockies. It was supposed to link the mineral-rich mountain towns around Breckenridge with the young Denver metro area, but Vidler never completed the project. The shaft sat unused until an engineer bought it in the 1950s and repurposed it to move water rather than ore. He acquired the rights to river water on the Breckinridge side of the tunnel, built a water pipeline through the shaft, and proposed to sell the river water to people in the fast-growing cities around Denver. The engineer didn’t have any confirmed buyers for the water, but he could store it in a reservoir until he made a sale.

In 1979, the Colorado Supreme Court dealt a blow to that scheme. A judge ruled that the engineer’s water purchases were “grounded on no interest beyond a desire to obtain water for sale.” If Colorado allowed such purchases, it would “encourage those with vast monetary resources to monopolize [water] for personal profit rather than beneficial use,” the court wrote. In other words, speculating on water was unacceptable. Judges in other states soon adopted similar rulings, creating a precedent that some legal scholars have called “the Vidler doctrine.”

About 15 years later, the Vidler tunnel and its water rights fell into the possession of one John Hart, a swashbuckling financier who was beginning a decades-long corporate takeover spree. Hart and his business partner had just taken over the Physicians Insurance Company of Ohio, or PICO. They transformed the moribund Midwestern insurance company into an umbrella corporation for buying and flipping distressed assets, including a Swiss railway operator, an Australian oil company, a million acres of rural land in Nevada, and a canola-seed crushing facility.

The Vidler tunnel’s history gave Hart an idea. He lived near San Diego, which relies in part on the Colorado River, and he could see that water was only going to get more valuable across the region, especially if real estate kept booming. Many farmers who had fallen on hard times were selling their irrigated land to developers, who repurposed irrigation water to supply new homes and golf courses. Hart wanted to profit from this slow transition away from agriculture, and he thought he saw a way to do it: Buy up water rights in the driest states, wait for the rights to rise in value, and sell them later on to developers that needed them for new housing. As long as the population of the West continued to increase, the price of water would increase as well — and with it PICO’s investment profits.

By acting as a broker for water rights, the PICO subsidiary that Hart called Vidler Water Company could get around the anti-speculation doctrine invoked in its very name. The tunnel engineer had sought to hold onto his water rights and make money by selling water to people who needed it. Vidler would just buy and sell the water rights themselves. This amounted to an elegant form of arbitrage: If a water right was worth more to a developer than it was to a farmer, Vidler could profit by flipping the right from the latter to the former.

Grist / Mikayla Whitmore

The only problem was that Hart didn’t know very much about the nitty-gritty details of water law, and he knew even less about the science of hydrology. In order for his plan to work, he had to find someone who could handle both. That someone was Dorothy Timian-Palmer, an engineer who had been Carson City’s municipal utilities director for around a decade before Hart poached her in 1997. Timian-Palmer declined to speak with Grist, but several sources who worked with and against Vidler described her as one of the nation’s foremost water experts.

“She is the most knowledgeable person about water in the country,” insisted Hart in an interview. He recalled how he and Timian-Palmer used to attend investment conferences where skeptical audiences heard the legendary oil tycoon T. Boone Pickens talk in vague and confused terms about his water investments. But when Timian-Palmer took the stage, introduced herself as a water engineer, and started rattling off facts about hydrology and hydraulics, all the attendees perked up and started taking notes.

“She’s very smart, very shrewd, and very tough,” said Paul Hultin, a lawyer who sued Vidler over one of its later projects in New Mexico.

Armed with an infusion of cash from PICO, Timian-Palmer and a small group of Nevada-based lawyers and engineers set about flipping water. They bought agricultural water rights along a river in Colorado and sold them to Denver-area developers. They bought tens of thousands of acres of farm- and ranchland in Arizona, Idaho, Nevada, and New Mexico and either sold the water rights to urban utilities, leased them back to farmers, or sold the land to developers. In one case the company made a fivefold profit after six years.

When developers wanted to use the water they’d just acquired on former farmland, they could fallow the irrigated fields and start pumping water into their subdivisions and power plants, fueling further housing expansion. Marc Reisner, the journalist who wrote that “water flows uphill towards money” in his seminal book Cadillac Desert, also joined Vidler for a few years as a part-time political consultant, believing the company’s projects could enable growth while avoiding the construction of harmful new reservoirs and dams.

In other cases, Vidler chose to sit on the water it acquired until its value went up. In California and Arizona, the company bought and stored water in so-called “underground storage facilities,” artificial aquifers that serve as subterranean reservoirs. The cities and farmers who typically use these kinds of water banks are usually trying to squirrel away water for use during dry years, but Vidler’s goal was to profit on the gradual increase in water prices.

In California’s agriculture-heavy Central Valley, for instance, the company took partial ownership of an artificial aquifer, then flipped its share to real estate developers and water utilities, making $25 million off the transaction in just a few years. In Arizona, meanwhile, the company built its own large storage facility west of Phoenix and filled it with more than 250,000 acre-feet of water from the Colorado River. (An acre-foot is equivalent to around 326,000 gallons, or roughly enough water to supply two homes for a year.) Vidler executives wrote in a 2004 financial statement that “continued growth of the municipalities surrounding Phoenix” and “the low level of Lake Mead,” the largest Colorado River reservoir, were both “likely to increase demand” for the water.

No one has ever accused the company of breaking the law with these transactions, but its strategy clashed with the legal principles established in the 1979 ruling against the original Vidler tunnel scheme. In order for Vidler to secure new water rights, it had to identify a “beneficial use” for each water source it wanted to claim. The company would tell state regulators that it wanted to use each given water right to supply a power plant, or a suburban development, or a farm. In its own financial statements, though, the company made it clear that using water was merely incidental to the company’s mission.

“Vidler seeks to acquire water rights at prices consistent with their current use, with the expectation of an increase in value if the water right can be converted to a higher use,” the company said in a 2001 annual report. “Vidler’s priority is to develop recurring cash flow from these assets.”

Grist / Mikayla Whitmore

Kyle Roerink, a water-conservation advocate who runs the nonprofit Great Basin Water Network, told Grist that he’s observed Vidler trying to find ways around the “beneficial use” doctrine for almost a decade.

“It’s a model where you’re trying to squeeze blood, profits, and water from stone, and they’ve been pretty successful at it,” he said. “[They’re] pushing the boundaries and testing the limits of what the foundational principles of Western water law are. It’s among the most dangerous elements of capitalism at play here.”

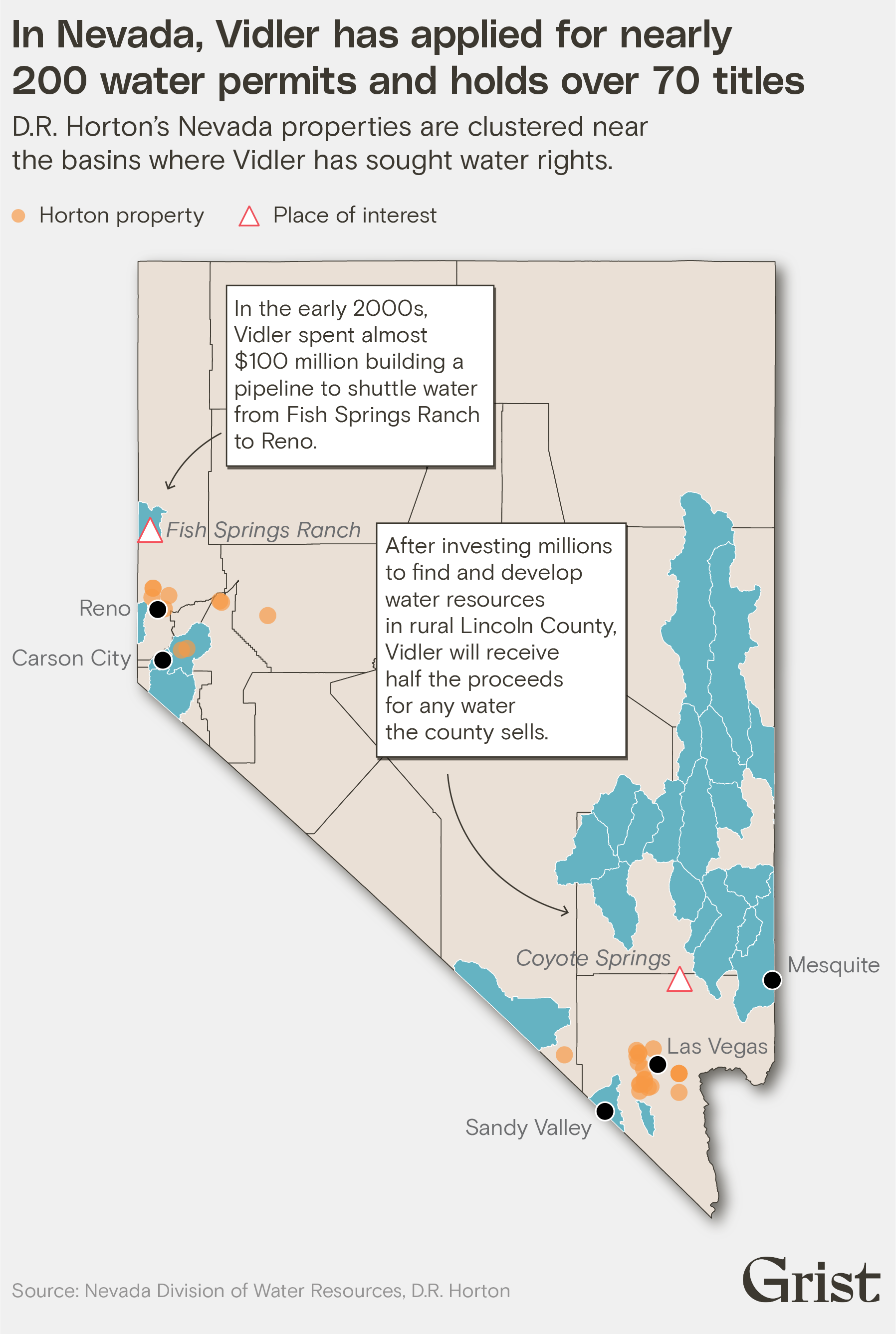

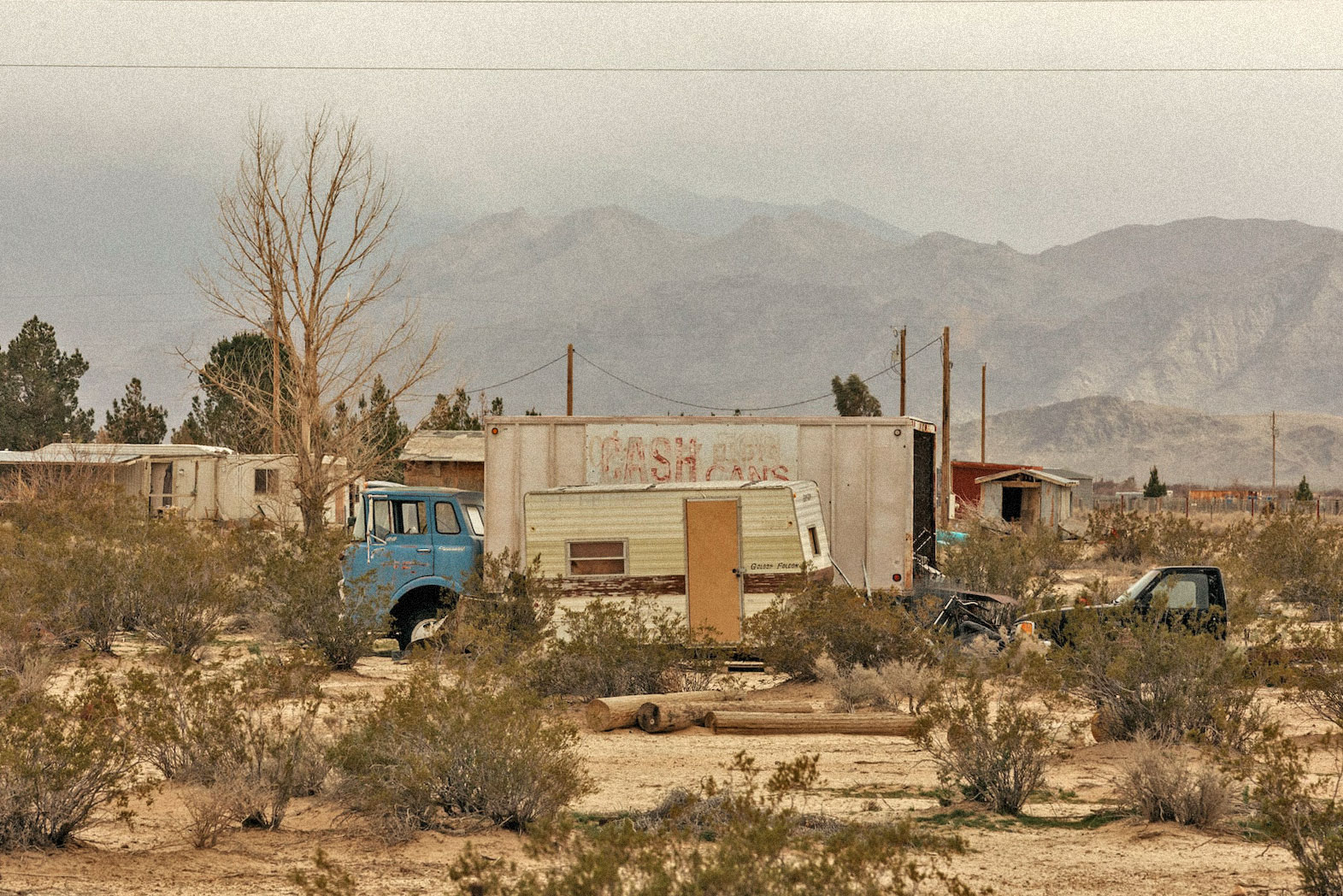

Indeed, Vidler’s loose regard for beneficial-use requirements has sometimes landed the company in hot water. In 1999, Vidler asked Nevada officials for permission to pump around 2,000 acre-feet of groundwater in Sandy Valley, a remote community of trailers and tumbleweeds about an hour southwest of Las Vegas. Vidler claimed to be applying for the water on behalf of a real estate company in Primm, a casino town on the California border. It laid out a far-fetched plan to build a pipeline that would move Sandy Valley’s water down to Primm across 25 miles of mountains, allowing developers to build housing and a theme park. The state government gave Vidler only some of the rights it asked for — but it amounted to almost as much water as the entire town of Sandy Valley used at the time.

A windy day in Sandy Valley, Nevada, a rural community where Vidler tried and failed to export groundwater. Mikayla Whitmore / Grist

When Sandy Valley residents heard about the project, they were furious. The area’s aquifer was already overdrawn thanks to a number of irrigated farms nearby. Residents depended on shallow household wells for their water, and they were terrified that those wells would go dry if the state let Vidler take its share.

“Vidler is a four-letter word here in Sandy Valley,” Al Marquis told me when I visited the town in February. A retired real estate lawyer who sued to stop Vidler on behalf of his town, Marquis is a quintessential Sandy Valley personality: He wears a ten-gallon-hat, flies amateur planes, and writes books of what he calls “cowboy poetry.” He recalled that a Vidler representative who showed up at a public meeting about the application found himself greeted by shouts and death threats from angry residents, who reminded him in no uncertain terms that nearly everyone in the valley owned a firearm.

In 2006, a judge overturned the state government’s decision to grant Vidler’s application, ruling that the company hadn’t proven it could put Sandy Valley’s water to beneficial use. Vidler claimed that the Primm real estate company needed the water to build apartments and a theme park, but the company couldn’t demonstrate that any of that development was really going to happen — the main evidence it had was a one-page wishlist drafted by the real estate company itself. In the absence of a clear beneficial use, the judge wrote, Vidler had no claim to Sandy Valley’s water, and the state had erred in giving the company permission to pump.

Grist / Mikayla Whitmore

“It appears to me that the company was formed for the sole purpose of speculating in and the hoarding of a public resource,” Marquis told Grist. He hypothesized that Vidler never wanted the water for Primm at all, and instead just wanted to flip it to someone else later on. “I gotta give them credit, in that they had foresight.”

Timian-Palmer and her fellow executives saw that the West didn’t have enough water, and they knew that was good news for Vidler: As drought got worse, the company’s assets would only get more valuable.

As the nation’s housing market boomed in the early 2000s, Vidler evolved. Instead of just buying and selling water rights that were already in use, the company began to search for unclaimed groundwater in remote parts of Nevada. It drilled new wells to bring that water to the surface, built new infrastructure to move it toward big cities like Reno and Las Vegas, and marketed it to developers and utilities. If Vidler could sell a new water source for more than it cost to develop and transport the water, the company would turn a profit.

“There seemed to be a void in terms of developing new supplies of water,” said Hart, explaining the opportunity. “Governments don’t really like to spend money for future citizens or future residents, and developers don’t want the upfront risk of having to go out to develop water for projects somewhere down the road.”

At the same time, major water sources like the Colorado River were showing signs of vulnerability as the region entered its current climate-fueled megadrought, lending more urgency to the search for untapped water. It could take years to secure regulatory approval for new groundwater pumping and even longer to build infrastructure to move that water around. Hart and Timian-Palmer were some of the only people in the West with the capital and expertise needed to pursue this kind of project.

The company’s first major experiment was a public-private partnership with a massive rural county about an hour north of Vegas. Lincoln County is one of the most sparsely populated counties in the nation — its population of 4,500 occupies a land area larger than Massachusetts — but it also boasted a hoard of untapped groundwater, most of which no one had ever tried to use. This water sits in some of the state’s shallowest and most remote aquifers, where it has accreted over thousands of years beneath chalk-white valleys.

Grist / Mikayla Whitmore

In the late 1980s, Las Vegas’s powerful water utility filed applications for almost all of Lincoln County’s unused water, more than 100,000 acre-feet in total, and proposed to build a pipeline that could bring it to Sin City. Officials in Lincoln County were still trying to fend off the big city when Vidler showed up and offered to act as a white knight. The company said it would invest millions of dollars to find and pump the county’s groundwater resources while also protecting those resources from Las Vegas. In exchange the company would get half the proceeds from any water the county sold.

Depending on whom you ask, this was either a boon for an impoverished rural county or a corporate takeover of a public resource. Wade Poulsen, the county employee who runs the water partnership, told Grist that Vidler had been “fantastic” and claimed that the county “would be nowhere without them.” But conservationists allege that Vidler was mining Lincoln County’s resources for profit.

“Vidler has turned Lincoln County into a water colony,” said Patrick Donnelly, a conservation biologist with the nonprofit Center for Biological Diversity who has litigated against groundwater usage in Nevada. “They own some serious water up there, and there’s this ideology of, ‘This water exists for us to benefit economically from it.’”

Grist / Mikayla Whitmore

The business thesis for the Lincoln-Vidler partnership was based on the assumption that the growth of Las Vegas would one day extend so far that it crossed the border into Lincoln County, more than 50 miles away from the city’s downtown. In the heady days of the early 2000s housing boom, this seemed like a real possibility; a number of real estate developers had staked out housing projects that could use Lincoln County’s water.

Chief among them was Harvey Whittemore, a friend of the late Senator Harry Reid and powerful casino lobbyist, who agreed to buy 1,000 acre-feet of water rights from Vidler in 2005. Before he went to prison for campaign finance violations in 2014, Whittemore spent more than a decade trying to build a megadevelopment called Coyote Springs in Lincoln County, pitching it as a desert metropolis that would someday contain 160,000 homes.

He managed to build a golf course on the development site, but a regulatory battle subsequently derailed the project and Whittemore never used Vidler’s water. Whittemore’s green, which was designed by golf legend Jack Nicklaus, still stands by itself on an empty desert highway, flanked by a massive sign announcing the future site of Coyote Springs, which another company is still trying to push forward. A tortoise habitat sits just a few feet away.

“They said at first they were gonna provide water for everybody, but the only people that [the Lincoln County partnership] ever actually tried to develop water for were [real estate developers],” said Louis Benezet, a longtime county resident. He said the water district initially discussed agricultural projects and growth opportunities in the county’s small towns, which were more attractive to county residents, but later focused on exporting water toward Vegas.

New homes under construction in Mesquite, Nevada. Grist / Mikayla Whitmore

Future builders in the area will likely need to acquire water rights from Vidler. Grist / Mikayla Whitmore

Timian-Palmer also pursued a similar strategy in fast-growing Reno in the early 2000s, targeting a property called Fish Springs Ranch about an hour north of the city. The land under the ranch contained enough groundwater for thousands of homes, and officials in the Reno area had long eyed it as a water source that could reduce the city’s reliance on the Truckee River, which drains out of Lake Tahoe. Instead of asking the local utility to help with the costs, as past entrepreneurs had, Vidler used private capital to push the project forward. The company built a pipeline that snaked through 28 miles of hilly terrain, ending in a cluster of valleys that were primed for future construction.

It was a transaction only Timian-Palmer could have managed, and one that demonstrated Vidler’s clout on water issues: Getting permission to build the project required conducting multiple federal environmental reviews, placating officials in multiple states, negotiating with the nearby Pyramid Lake Paiute Tribe, and passing a bill to ratify the details in Congress. Even after spending almost $100 million to permit and build the project, Vidler still stood to profit by selling the water to developers in Reno’s suburbs — there were almost no alternative water sources in the valleys north of Reno, so Vidler would be able to set the price.

Alas, Hart and Timian-Palmer had terrible timing. Just as the company’s projects in Reno and Vegas seemed to be taking off, the U.S. housing market started to wobble, led by a wave of foreclosures in Nevada and other Western states. When the market collapsed, builders and developers nixed all their suburban development projects, sold off their land, and pulled out of their agreements to buy water from Vidler. The company had moved heaven and earth to secure water for Nevada’s future growth, but that growth seemed to evaporate overnight.

“When Vidler started construction on the pipeline project, essentially, all of the water was spoken for,” said John Enloe, an official at the water utility that serves the Reno area. Enloe worked with Vidler on the pipeline project. “By the time construction was completed, the Great Recession hit, and everyone backed out. There just wasn’t a need for the water.”

Even as the housing market started to rebound from the Great Recession, Vidler spent much of the next decade running up against a very simple problem: The company had spent millions of dollars to develop new water resources across the West, paying to drill test wells and fill out lengthy water-right applications with the state government, but it couldn’t find buyers for all the new water it had developed.

That was in part because regulators had started to question the logic of growth. By the time the Western real estate market surged back to life in the late 2010s, the megadrought that gripped the region was well into its second decade. Major reservoirs in the Sierra Nevada and the Colorado River were bottoming out, and many rural communities were starting to see their wells go dry. This shortage had begun to stoke new concerns about overreliance on groundwater, and Vidler soon found itself facing new opposition from courts and regulators.

In a sign of its commitment to aiding development, Vidler fought back against these restrictions with a vengeance, litigating and lobbying to ensure its projects could move forward.

Grist / Mikayla Whitmore

A case in New Mexico demonstrated how aggressive the company could be in snapping up water. In the early 2000s, as Vidler was looking to expand into the state, Timian-Palmer connected with a rancher named Rob Gately. Gately owned a large chunk of land in the mountains east of Albuquerque and was seeking to build a big suburban development on the empty parcel. The area was far from prime real estate: It boasted a few dozen houses scattered across a stretch of wind-blown desert, but nothing else in the way of commerce. At least one other proposed development had already fallen through. Even so, Vidler offered to help Gately secure water. It applied to the New Mexico state government for permission to pump 700 acre-feet of water from the area aquifer, spending almost $6 million during the application process.

But Vidler’s own models showed that water use from the new development would cause water levels in the aquifer to drop, endangering residential wells. “People are already having problems with water, and that’s well-known here,” said Joanne Hilton, a hydrologist who lives in the area around the proposed development site and relies on a household well.

By 2017, residents had taken Vidler to court in an attempt to stop the project. Several key executives had to take the stand, including Timian-Palmer and her longtime right-hand man, executive vice president Steve Hartman. During a series of testy depositions, it emerged that Vidler seemed to be stretching the truth about the “beneficial use” it planned for the water. The company claimed that Gately was the mastermind behind the development, but the Montana holding company he was using for the project had been dissolved and no one from Vidler seemed sure about where he was based.

During one deposition, the lawyer for the area residents asked Hartman if he could provide specifics about how Vidler wanted to use the water. Just what kind of development was Gately trying to build, and how much water would it need? Hartman struggled to answer.

“So assuming that you get the permit and the case becomes final, then at that point you and Mr. Gately are going to sit down and talk about what’s next, is that right?” the lawyer asked.

“Yes,” Hartman said.

“And at this point you have no idea what that is?” the lawyer asked.

“I do not,” Hartman replied.

Two years later, the court tossed out Vidler’s application, ruling that the project would have risked taking water away from area residents and would conflict with New Mexico’s statewide goals for water conservation.

Grist / Mikayla Whitmore

Faced with obstacles like these, Vidler had to go on offense. The company donated more than $275,000 to Nevada political candidates between 2008 and 2022, increasing its annual contributions in the years that followed the Great Recession. Hartman became a fixture in the Nevada legislature, lobbying on dozens of water bills, many of them concerned with obscure points of water law. During the present legislative session, as the company prepares to defend its water interests in Lincoln County, it has hired Nevada’s premier lobbying firm, whose other clients include Amazon and Uber.

In recent years, Timian-Palmer and Hartman have tried to scrape value from Vidler’s water assets wherever they can. They sold off some of their banked Arizona water to a golf course in a Phoenix suburb, making a more than threefold profit. They returned to Sandy Valley in 2016 to apply for water on a different patch of land, only to run into trouble once again with Marquis, who discovered that the company hadn’t told an area landowner it was going to apply for the water under his land. In litigation over the Coyote Springs development in Lincoln County, they conducted geological testing to prove that they should be able to tap an aquifer the state had deemed too vulnerable, alleging the existence of an underground fault they named “Dorothy’s Fault,” apparently after Timian-Palmer. They even went so far as to demand that Nevada cut off water deliveries to a town near a basin where Vidler had been prevented from pumping water, arguing that the town shouldn’t get to use water, either.

“They’re engaging in these processes for one reason and one reason only, and that’s to one day make money,” said Roerink, the water conservation advocate.

Neither Vidler nor D.R. Horton responded to extensive requests for comment on this story. Dorothy Timian-Palmer initially agreed to an interview in response to a request from Grist, but a Horton spokesperson later said that the company wouldn’t be participating in the story. After Grist visited Vidler’s office in Carson City, a Horton spokesperson offered to respond to a list of questions, but company representatives failed to do so before publication.

Even as Vidler sought buyers for its water rights, PICO went through a shakeup: Shareholders grew dissatisfied with Hart’s high salary and with the slow return on their investments. They ousted Hart and replaced him with a new chairman who soon cut costs, selling off PICO subsidiaries. Vidler’s assets were more difficult to cash out: The company had spent tens of millions of dollars on water projects like the ones near Reno and Albuquerque, and it wasn’t clear when those projects would start making money. The easiest way to make the company’s shareholders whole was for another company to buy Vidler outright.

Timian-Palmer and her fellow executives started trying to find a buyer as early as 2017, when they hired a bank to solicit potential offers, according to a corporate filing. The bank contacted more than 150 different potential buyers, but none of them showed much interest. The main problem was that nobody seemed to be interested in acquiring Vidler wholesale. As the search continued, it became clear that Vidler needed a company that wanted to use its executives’ water expertise, not just sell off the assets Timian-Palmer had acquired — in other words, a company that needed Vidler as much as Vidler needed it.

It took a few more years and a millennium-scale drought, but in the final months of 2021, Vidler found a company that could finally make its development dreams a reality.

D.R. Horton is a tight-lipped company, and it didn’t say much about its purchase of Vidler. In a press release published on the day of the acquisition, the company noted that “Vidler owns a portfolio of premium water rights and other water-related assets … in markets where D.R. Horton operates.” A few weeks later, when a stock analyst asked about the purchase on an earnings call, an executive replied that “we put out pretty much what we’re going to say about Vidler in the press release.”

Even so, the logic of the transaction was apparent: The places where Vidler owned substantial water rights were also places where Horton was building homes. At a shareholder meeting in 2021, Timian-Palmer told investors that Horton was “moving like gangbusters” in the north suburbs of Reno, planning multiple subdivisions that could purchase water from Vidler’s long-dormant Fish Springs Ranch pipeline. The valleys north of Reno are now home to a horde of uniform subdivisions, most of them sandwiched against each other just off the freeway. Many of the largest belong to Horton. If the city’s recent growth spurt continues, Vidler’s pipeline will be the only available water source for future builders.

Horton is also building several developments east of Carson City on a fast-growing industrial corridor near a Tesla factory. In a 2021 financial statement, Vidler noted that “there are currently few existing sustainable water sources to support future growth and development” in that corridor, except for Vidler’s own supplies. Horton also has numerous active projects in central Arizona, where Vidler has banked almost 300,000 acre-feet of water underground. Together, the two companies have everything they need to capitalize on the West’s post-pandemic population boom.

Vidler has always operated more like a fixer than a financial trader, not just flipping assets but developing new water resources in the driest areas. Several sources who spoke to Grist theorized that this was why Horton paid so much to acquire the company.

“If you’re a homebuilder, your best option is to do what Horton has done — go out and find more supply,” said Grady Gammage, a real estate lawyer who has represented Greenstone, another water broker founded by a former Vidler employee, and several homebuilders. “What Horton is likely thinking is that you’re faced either with doing a deal [to get new water], or trying to build that expertise in-house.”

The future of the West depends on whether, and to what extent, these companies can secure these deals and expertise in the face of new regulatory restrictions and supply constraints.

Nowhere is this dynamic clearer than in the western suburbs of Phoenix, where developers and builders have thrown up tens of thousands of homes that rely on groundwater from fragile aquifers. Earlier this year, Arizona’s new governor released a study that showed the area has much less water available than was previously thought. State law requires developers to show that proposed homes have a hundred-year water supply, and officials have now decreed that there isn’t enough groundwater in the area to provide for any more new subdivisions in the southern and western outskirts of the city.

This has left several gigantic development projects stuck in limbo, including ones with which Horton was involved. It has also forced developers and homebuilders to look for alternate sources of water, including from underground storage facilities like Vidler’s. The company’s biggest underground aquifer contains enough water to supply about 2,000 homes for a hundred years each.

Grist / Mikayla Whitmore

“It’s a challenge to find other supplies right now, to say the least,” said Spencer Kamps, vice president of legislative affairs at the Central Arizona Home Builders Association, which advocates for builders and real estate. “A number of investments have been made out in the area under the assumption that there was water available for growth.” But many people in the industry now worry that those assumptions were mistaken.

You wouldn’t know it from visiting the area. Earlier this year, I presented myself as a potential home buyer in the Phoenix suburbs where the state has identified a groundwater shortage, touring several Horton developments. These developments are tight clusters of cookie-cutter homes, surrounded for the most part by empty desert or isolated alfalfa fields. Construction appears to happen rapidly: As I drove through the developments, I found myself slipping back and forth between streets full of finished homes with xeriscaped lawns and streets where construction crews were still hammering at open timber frames.

In speaking with Horton sales representatives on my tours, I asked about water access, saying I’d heard there were issues in the area. The representatives brushed off my concerns, saying they “try to stay out of politics,” or that they “don’t believe they would allow growth out here” if there wasn’t enough water.

Grist / Mikayla Whitmore

That is far from certain. Timian-Palmer and her colleagues have spent decades finding water sources for suburban developments like these. While the homes they helped build will last for many decades, the water that supplies them may not. Without ample rain to replenish them, the small and fragile aquifers that Vidler has tapped could someday empty out, leaving future homeowners high and dry. This has already started to happen in rural parts of the West where agriculture is dominant, and it may ultimately happen to the suburban developments Vidler is now helping to build.

Mike Machado, a former California state senator who served on PICO’s board of directors between 2013 and 2017, said the company’s business model makes him worried for the future of those developments.

“The biggest challenge for Vidler is whether or not the resources they have are renewable,” he told Grist. “It’s great to be able to have these resources, but if all you’re doing is mining them, at some point in time, you’re not going to have them. So that is creating a false sense of security for those that are relying on the resource.”

Horton’s sales representatives in Arizona have no such misgivings. For the moment, at least, the building boom is very much alive.

“If we continue to grow out here, the people living here will have water,” one sales representative told me. “What, are we just not gonna have water when we turn our faucet on?”

Correction: An earlier version of this article incorrectly referred to Patrick Donnelly of the Center for Biological Diversity as an attorney.

This story was originally published by Grist with the headline The little-known Nevada company making millions off the western water shortage on May 3, 2023.

Georgia’s hedge against climate change: the Okefenokee’s peat

“Not the kind of life a human being should live”

Why Biden is backing the Mountain Valley Pipeline

If there’s a bustle in your hedgerow, don’t be alarmed now

It’s just a spring clean for the May Queen

— “Stairway to Heaven” by Led Zeppelin

The classic song demands some investigation. Just what is the May Queen throwing out? And why is it in the hedgerow? Is she doing this work herself or has she hired a cleaning service? And is that hedgerow in compliance with the property convenents anyway?

Inquiring minds want to know. Alas, we won’t get to the bottom of that today but I will use this opening day of May to clear out a few things from my own hedgerow.

Biden’s energy secretary backs the Mountain Valley Pipeline

One of the most curious political developments recently was the decision by U.S. Energy Secretary Jennifer Granholm to write a letter to federal regulators in favor of the Mountain Valley Pipeline, the natural gas pipeline from northwestern West Virginia to Chatham whose construction is held up by lots of legal complications.

On the one hand, Politico reports that “the whole Biden coalition is built around this commitment” on climate change. Yet here is the administration backing a project that critics consider “dirty energy.” What gives?

First, Biden has never been a purist on energy. When he was running in 2020, he was always mindful that he needed to carry Pennsylvania, where natural gas production is big.

As president, he has angered some on his left recently when he approved exports of liquefied natural gas from an Alaskan project. “Joe Biden’s climate presidency is flying off the rails,” claimed a spokesman for Friends of the Earth. Of course, Biden is also trying to play a complicated game of three-dimensional chess – and one level of that game is trying to increase American LNG exports to elbow out Russian exports and make it easier for countries to stop buying Russian gas while that country is making war on Ukraine.

The politics of Granholm’s support for MVP is probably much simpler than geopolitics. It’s about a more domestic brand of politics – helping out U.S. Sen. Joe Manchin, D-West Virginia. The most unreliable Democratic senator surprised many by voting for the so-called Inflation Reduction Act – also called the “climate bill” – last year. What he wanted in return was approval for the MVP and so far he hasn’t gotten it. He’s also wavering on, well, lots of things. Biden needs Manchin’s vote. He also needs Manchin, as problematic as he may be for Democrats, to get re-elected next year – and Manchin will face a strong challenge from West Virginia Gov. Jim Justice. Democrats may think Manchin isn’t much of a Democrat, but they’d sure rather have him as a senator from West Virginia than they would a Republican.

So Granholm’s letter can be read on two levels. One, the administration is trying to do a favor for Manchin. Two, it may be that the administration really does believe that the Mountain Valley Pipeline “will enhance the nation’s critical infrastructure for energy and national security.” That would not be out of line with Biden’s actions elsewhere. Politico has a good analysis of all this: “Why is Biden backing Manchin’s pet pipeline?”

It should also be noted that Granholm’s letter is mostly symbolic. Federal regulators have already approved the pipeline; it’s the courts that have held up the project. Granholm’s letter doesn’t do anything, but if sending this to regulators helps mollify Manchin for awhile, I’m sure the White House will think it’s worth it.

Speaking of Manchin, he cast the decisive vote in favor of that Inflation Reduction Act. Here’s how that’s worked out:

What kind of incentives would we have to pay for a big employer at the Southern Virginia Mega Site?

A few weeks ago, I wrote about how the Canadian province of Ontario had won out over Oklahoma for a Volkwagen electric vehicle battery plant. Oklahoma wasn’t very happy about that. While Virginia wasn’t in the running (at least that we know of), I pointed out that the lessons from that Ontario vs. Oklahoma competition that might apply here as we try to land a big employer for the Southern Virginia Mega Site in Pittsylvania. For instance, Volkswagen said one of the reason it picked the Canadian site was because Ontario has so much de-carbonized energy. VW also cited something that American conservatives have come to loathe – “high ESG standards,” the ESG standing for “environmental, social and corporate governance.” Some might say that Volkwagen picked Ontario for 2,500 manufacturing jobs because Canada is “woke.”

At the time, we didn’t know what kind of incentives Ontario had offered but I wrote that they weren’t likely the decisive factor. And they may not have been – although we now know that they were higher than Oklahoma. Oklahoma offered about $700 million in incentives. Ontario put up about $883 million (that was $1.2 billion in Canadian dollars), with most of that coming from the national government, not the provincial government. Virginia knows form its Amazon courtship that incentives aren’t the only thing that matters – other states offered far more than Virginia’s $750 million, but look who won.

That’s not the whole story, though. Canada has also announced that it’s paying $13.2 billion – that’s billion with a b – in subsidies to VW. That’s $13.2 billion in Canadian money, so a mere $9.71 million in our dough.

Canadian officials said they were forced to do this because of the so-called Inflation Reduction Act, aka “the climate bill,” that the U.S. Congress passed last year. That bill included $369 billion (in our money) of incentives for electric vehicles and other clean energy technologies. Reuters reports that the Canadian deal for VW “showcases how the U.S. green package . . . is putting pressure on other governments to ramp up financial incentives to lure investments.” Neither Europe nor Canada likes that bill for the same reason that American Democrats (and the bill passed on party-line votes) liked it: The law includes strong financial incentives for companies to locate in the United States. Prime Minister Trudeau referenced this in his announcement about the size of the Canadian subsidies: “Other parts of the world, including our neighbors to the south, were willing to put up an awful lot of money to get this project.”

Oklahoma’s governor lamented that his state had to compete with a whole country, but Canada lamented that it had to compete with a whole country, too – and a much bigger one. The lesson for us – other than to marvel at how U.S. law is forcing Canadian taxpayers to dig deeper – is about how intense the competition for electric vehicle battery plants is. As I’ve pointed out before, there are only so many of these plants that will be built. Set aside Canada’s subsidies to match the Inflation Reduction Act; just looking at the direct grants – Canada’s $883 million to Oklahoma’s $700 million – and we get new market information as to what the going rate is. For what it’s worth, these incentives for 3,500 jobs were lower than what Georgia offered in incentives for the 8,100-job Hyundai plant that passed over Pittsylvania County last year. Georgia put up $1.8 billion for that. Meanwhile that Ford battery plant that Gov. Glenn Youngkin nixed because of its partnership with a Chinese company? Michigan approved $630 million in incentives for that project. Wonder what Virginia would pay for a big employer at the Southern Virginia Mega Site?

Roanoke’s unique hockey culture

Everything is connected, even in a spring cleaning. We started with what Politico called “Manchin’s pet pipeline,” then looked at the a situation that involved how the climate bill he voted for was playing out in Canada, and now we’ll end with a local tie-in to the quintessential Canadian sport – hockey.

Tonight, Roanoke’s minor league hockey team, the Roanoke Rail Yard Dawgs, plays its first home game in a best three-of-five series for the championship of the Southern Professional Hockey League. (The series with the Birmingham Bulls is tied at one game apiece). I would be remiss if I didn’t point out that this team has been successful both on and off the ice – something previous minor league hockey teams in Roanoke haven’t been.

The Roanoke team had the third highest average attendance of any team in the 10-team league this year – averaging 4,449 fans per game.

I won’t dare offer a sports prediction for Roanoke’s series with Birmingham but I will point out that Roanoke has a bigger hockey fan base than the Bulls do, even though Birmingham’s metro area has four times as many people. Birmingham’s been averaging just 2,886 fans per game. It’s probably wrong to compare sports – apples and oranges, that sort of thing, but I will offer this comparison anyway. The Roanoke Valley’s minor league hockey team draws more fans than its minor league baseball team does (the Salem Red Sox last year averaged 2,719 fans per game).

The Roanoke Valley has had hockey off and on since the late 1960s – the Salem Rebels took the ice in 1967 – although there was a decade-long time-out before this current team arrived in 2016. It’s been by far the most stable hockey franchise the Roanoke Valley has seen. The persistence of hockey in the Roanoke Valley is one of those things that often mystifies – and fascinates – those who don’t know the region. Sometimes we in this part of the state moan about all the things we don’t have that the rest of Virginia does. Here’s an example of something we have that, say, Richmond doesn’t. So, yes, tonight much of Roanoke will celebrate the first days of May by watching a sport on ice.

The post Why Biden is backing the Mountain Valley Pipeline appeared first on Cardinal News.

Climate change is changing public health

The Department of Health’s expanding climate health team, which also includes a scientist who studies insects as disease vectors and experts on water quality and climate justice, is part of a deepening understanding of how profoundly climate change affects human health. Recent studies paint a grim picture: In addition to increasing the severity and frequency of both extreme heat events and wildfires, climate change is creating disease hotspots while also making some infectious diseases worse. This realization is changing health experts’ training, including at Harvard Medical School, which recently added a climate curriculum to all four years of instruction.

The Washington climate team members approach their work with the foundational understanding that climate exacerbates historic injustices. “Communities of color, children, older adults and pregnant people are all more sensitive to the impacts of climate change,” said Kelly Naismith, the agency’s newest climate epidemiologist. “They’re more vulnerable.” She plans to monitor emergency room data in close to real time to see how high temperatures drive diagnoses and patient numbers. “One thing we’ve learned in the past couple years, during heat waves, is that there’s a pretty big increase in ER visits,” she said.

“Communities of color, children, older adults and pregnant people are all more sensitive to the impacts of climate change.”

Michelle Fredrickson is quantifying the unequal distribution of climate impacts. She’s using LiDAR, or Light Detection and Ranging, a type of laser scan, to determine how tree canopy, green space and asphalt coverage affect neighborhood temperatures during heat waves. Her work builds on research that has already shown how widespread those inequities are. A nationwide study published in 2020 found that areas subject to racist housing practices in the 1930s experience hotter temperatures today: Lower-income people and people of color live in areas with less greenery and more asphalt, which magnifies heat.

Washington epidemiologists are using existing data about air quality and heat-related deaths, things that are historically monitored by public health departments, for a new purpose: illuminating their connections to climate change. “When you start pulling together climate data and environmental hazard data, it starts to paint a clearer picture of the existing environmental justice issues in the state,” said Rad Cunningham, senior epidemiologist. “You start seeing patterns of how those issues are going to get worse over time.”

But they’re not just addressing current issues; they’re also trying to determine what the future will look like and how to prepare for it. “It’s a paradigm shift,” Cunningham said. A proactive approach can help states save lives, blunt unhealthy trends and be better prepared for emerging climate-driven threats.

That may improve the situation on the ground in Washington in the coming years. School evaluations could show where state funding is most needed to retrofit buildings and design new ones to make spaces cooler and cleaner on hot, smoky days. The team is working to make public health tools and messaging — such as tips on how to protect yourself from wildfire smoke with box fans and filters — less jargony and more useful. The epidemiologists are collaborating with newly created, climate-focused local public health positions across the state.

The climate health team’s total budget — $1.8 million this fiscal year — comes from state and federal sources. Washington is looking to climate health programs in other states like California and Colorado for inspiration. And the epidemiologists hope to learn from places dealing with problems that aren’t as prevalent in Washington — yet. For example, warmer temperatures are allowing ticks to spread into areas they previously weren’t able to survive. In response, Michigan’s Department of Health has become an expert on ticks and tick-borne diseases, such as Lyme. “We have a lot to learn from them,” Cunningham said. “We have a chance to do what they wish they would’ve done.”

Kylie Mohr is an editorial fellow for High Country News writing from Montana. Email her at kylie.mohr@hcn.org or submit a letter to the editor. See our letters to the editor policy.

Catawba College becomes first campus in North Carolina — and the Southeast — to go carbon neutral

The small, private liberal arts school is among just 13 colleges in the country to achieve net-zero so far.

Catawba College becomes first campus in North Carolina — and the Southeast — to go carbon neutral is an article from Energy News Network, a nonprofit news service covering the clean energy transition. If you would like to support us please make a donation.

Public lands or private profit? West Virginia RV campground debate raises questions over role of state parks

On warm spring days, the forests of Cacapon Resort State Park sprout bushy, lime-green leaves as people walk along wooded trails, fish in the lake, birdwatch or share a meal at a picnic table.

For nearly a century, the park’s old forests, sweeping views and peaceful waters have attracted visitors, many seeking a nature-filled respite from the Baltimore-Washington D.C. rat race. But the park holds a particularly special place in the hearts of local residents who often gather there with friends and family.

“When I bring my grandkids over here, it’s the happiest time I can imagine,” said Craig Thibaudeau, who lives nearby. He recalls fond memories of playing with his grandchildren on the swing sets or beaches and fishing with his brother from Texas.

So when state officials announced plans to build a private RV campground in the park and one of the proposals included several hundred campsites, he was concerned.

“You lose the humanity of this park if you go corporate,” Thibaudeau said. “And that’s the bottom line. It’s the humanity that makes it so special.”

In public protests, he and dozens of others argued the environmental and social consequences of the development would be devastating.

The outcry eventually led the West Virginia Division of Natural Resources to abandon the current campground effort entirely, and the agency is now seeking public input on what facilities it should add to the park.

The fierce debate over the RV campground at Cacapon was the first test of a law passed last year allowing private development of facilities in almost all state parks. While the project is on hold, the law remains on the books and state officials could explore development at Cacapon or another park in the future, setting up another struggle over the role of private companies on public land.

Why a request for campground proposals sparked intense backlash

The dustup over development in Cacapon Resort State Park started in December, when the WVDNR put out a request for proposals from private companies interested in developing both campgrounds and recreational facilities at the park.

“The WVDNR welcomes community engagement for this development project and will work with local stakeholders to maintain Cacapon’s natural environment as currently enjoyed,” Commerce Secretary James Bailey said in a March statement releasing the three proposals received from different companies, all for a combination of RV campgrounds and other amenities.

One plan, by a Harpers Ferry-based company, would create 50 RV campsites and also provide a shuttle service. A second proposal by a Berkeley Springs-based company sought to partner with the park on the development of an RV campground on nearby private land.

The third plan by Blue Water Development in Maryland, contained a number of options, including the creation of as many as 350 RV campsites, a floating dock called an aquabana, mini-golf, and in one proposal, a “snowflex” that would involve using artificial snow to support year-round skiing and snowboarding.

Community members quickly rallied against this plan, launching local protests, community meetings, and an online petition to withdraw the request for proposals that received more than 1,000 signatures.

They argued that hundreds of campsites and the recreational facilities would create a disruptive amusement park-like atmosphere and advocacy groups raised concerns that some of the new amenities would affect the affordability of the park.

“Cacapon is a very unique, very mountainous area,” said Mike Jones, the public lands campaign coordinator for the West Virginia Rivers Coalition. “Putting in these kinds of mega-projects is just incompatible with that.”

In a letter to state officials, the Morgan County Commissioners said that a large RV campground would strain already struggling sewer and road infrastructure and “diminish many of the reasons that folks visit our park to begin with: the natural beauty, the historical significance, and the peaceful tranquility.”

State parks officials canceled a public hearing set for mid-April after a lawsuit brought by a citizen argued that they did not notify the public as required by law. Several days later, they announced that they would not be moving forward with any of the three proposals and would seek further public input.

Critics note a new state law allows for private development in parks

While plans for an RV campground at Cacapon have been put on hold for the time being, advocates pointed to the proposals as confirmation of their concerns around HB 4408, a bill passed in 2022 that allows for private companies to develop projects and facilities in all state parks, except for Watoga State Park, the state’s largest.

The proposal was heavily criticized by environmental and conservation groups when it was introduced last year, with local groups, and some former state parks employees arguing that the measure would lead to development projects that could irreparably damage the parks and would also effectively privatize significant parts of them.

“Our state parks, up until this administration, never seemed focused on being profit-making centers, at least not for private businesses,” said Angie Rosser, executive director of the West Virginia Rivers Coalition.

In an email, House of Delegates spokeswoman Ann Ali noted that the 2022 legislation was requested by the WVDNR. Del. Mark Dean, a Republican from Mingo County and the lead sponsor of the legislation, said in a statement that he supported the bill because he “thought it could provide a new opportunity for outdoor recreation to expand throughout the state, especially those activities with high start-up costs.”

Local residents and delegates however, have criticized the measure in recent weeks.

“I tried to talk it down. I changed about five or six votes,” Del. George Miller, R-Morgan, told a local online news outlet of his decision to oppose HB 4408 last year after initially backing it. “But it would have passed anyway. We have to deal with it now.”

Residents say environmental concerns are paramount

During recent protests against the proposed development, some residents held signs with sharp slogans, like “CCC does not mean Corporate Cash Cow” – a reference to the Civilian Conservation Corps. The New Deal-era employment program created millions of conservation jobs for young men and hundreds of state parks – including Cacapon.

The park’s roots in a movement intended to preserve public lands made recently proposed development all the more concerning to those living nearby. In addition to aesthetic worries about hundreds of new RV campsites, residents also had environmental concerns.

Development would’ve likely included cutting down trees on several acres of land, paving over soil with concrete and draining a wetland to create a beach. All of these measures can increase the likelihood of flooding, already a major concern for West Virginia due to its many mountains, valleys and river systems.

Five years ago, park visitors and nearby residents alike were evacuated when the Cacapon River rose more than seven feet above the flood stage.

“They evacuated my street. And it wasn’t voluntary. They stayed there until you left,” said Morgan County resident Dale Kirchner, who filed the lawsuit over the public hearing and lives very close to the park. “So now if you have acres more of runoff – not only for the campground, but the amenity areas – how much worse is that going to be? Do we really want to take a chance with global warming and the storms getting worse?”

Kirchner and others also expressed concerns about safety. If the park could suddenly host an additional thousand visitors, they worried there’d be more campfires and people partying. They worried that could lead to more injuries and forest fires. Just last week, multiple forest fires burned across more than 1,500 acres in nearby Pendleton County, eventually setting ablaze beloved environmental landmark Seneca Rocks.

Such a fire in Cacapon could endanger priceless resources. The park is home to two endangered species, the wood turtle and the harperella, a plant with white flowers that typically grows along shallow streams. It’s also home to old-growth forests, often described as irreplaceable because of their unique ability to provide a haven for biodiversity, reduce flood risk and mitigate the effects of climate change — in a way younger forests can’t mimic.

As state moves forward, local residents say their voices must be heard

After scuttling the current proposals for an RV campground, the state must now go back to the drawing board. The Division of Natural Resources has released an online survey about future development that will be open until late May.

Beyond that, it is unclear what will happen next — neither the WVDNR nor State Parks responded to questions about the now-scrapped proposals or future plans at the park.

But for Morgan County residents, the defeat of the RV campground bids presents a clear victory for local efforts to ensure community input in the park development process. And for critics of privatization efforts, the recent controversy likely provides ammunition for future debates over development in other parks.

Now with the new law on the books, almost all state parks, including Cacapon, could be chosen for private development, raising the question again of whether public lands should be altered for the sake of economic growth.

Public lands or private profit? West Virginia RV campground debate raises questions over role of state parks appeared first on Mountain State Spotlight, West Virginia’s civic newsroom.

After the feds accidentally burned down their homes, they made it hard to return

He calls it the “tin can.” Its heater is broken. The cold creeps through its thin walls. Wind rattles the wooden cabinets. But it’s all he could afford.

A year ago, two runaway fires set by the U.S. Forest Service converged to become the Hermits Peak-Calf Canyon wildfire. It rode 74 mph wind gusts, engulfing dozens of homes in a single day as it tore through canyons and over mountains.

The blaze became the biggest wildfire in the continental United States in 2022 and the biggest in New Mexico history. And it was the federal government’s fault: An ill-prepared and understaffed crew didn’t properly account for dry conditions and high winds when it ignited prescribed burns meant to limit the fuel for a potential wildfire.

By the time the blaze was fully contained in August, it had destroyed about 430 homes, according to the Forest Service. Monsoons helped extinguish the fire, but they spurred floods that caused more damage.

FEMA stepped in to help, offering cash for short-term expenses and, after the state requested it, temporary housing to 140 households. But the federal government has acted so slowly and maintained such strict rules that only about a tenth of them have moved in, an investigation by Source New Mexico and ProPublica has found.

A year after the fire began, FEMA says most of the 140 households it deemed eligible for travel trailers or mobile homes — essentially, people whose uninsured primary residences sustained severe damage — have found “another housing resource.”

What the agency doesn’t say: For some, that resource is a vehicle, a tent or a rickety camper. It’s a friend or relative’s couch, sometimes far from home. It’s a mobile home paid for with retirement funds or meager savings.

The fire upended a constellation of largely Hispanic, rural communities that have cultivated their land and culture in the shadows of the Sangre de Cristo Mountains for hundreds of years. Many residents can find their family names on land grants issued by Mexican governors in the 1830s.

Now they’re dispersed across the region, even out of state. Source New Mexico and ProPublica obtained records from local officials and volunteer groups and eventually interviewed more than 50 people who between them lost 45 homes.

Many of them said FEMA’s trailers were offered too late, cost too much to get hooked up or came with too many strings attached. Several said they went through multiple inspections, only to learn weeks later that one rule or another made it impossible to get a trailer on their land. In some cases, FEMA officials told people that their only option was a commercial mobile home park, miles down winding, damaged mountain roads from the homes they were trying to rebuild.

People who between them lost 17 homes said they withdrew from the housing program because of those problems.

As of April 19, just 13 of the 140 eligible households had received FEMA housing. Only two of them are on their own land.

Martinez said he got a call from FEMA in mid-October, seemingly out of the blue. By then, he had been living in the tin can for a couple of months. As temperatures dropped, he had started sleeping on the couch, closer to the space heater.

A FEMA representative asked if he needed a trailer to live in.

“I told them it was too late,” he said. “Way too late.”

FEMA said terrain and weather, among other factors, presented challenges in providing housing to survivors. But the agency said it made an exception to its rules by providing trailers and mobile homes in the first place — normally such programs are reserved for disasters that displace a large number of residents.

The agency said it tries to place temporary housing on people’s property, but couldn’t in many cases because of federal laws and its own requirement that trailers be hooked up to utilities. State and local officials have asked the agency to loosen its rules, but it hasn’t.

FEMA knows it has a problem with its response to wildfires. A 2019 Government Accountability Office report said FEMA’s housing programs are better suited to help those displaced by hurricanes and floods because some victims can remain in their damaged homes, there’s often more rental housing in those areas and there’s more space for large mobile home parks than there is in the rugged mountains scorched by wildfires.

FEMA agreed with the findings and said it would explore providing housing funding to states because they’re better positioned to guide recovery. That didn’t happen after the Hermits Peak-Calf Canyon fire.

Last month, Martinez woke up on the couch in severe pain from a swollen bladder. Now he needs frequent medical appointments to check his catheter and figure out what’s causing the pain. His sister has been trying to get him a FEMA trailer in a commercial park closer to a clinic in the town of Mora. It’s just 8 miles away, but it can take 45 minutes to drive there.

What neither of them knew when he bought that old trailer last summer is that doing so made him ineligible for a FEMA trailer.

Martinez wants to stay on his property if he can. His great-grandfather once owned the land where he built that cabin. He raised his hands to show his stiff, swollen fingers. “They ain’t worth shit now,” he said. “But a man builds his own castle, right?”

The cost of free housing

By mid-June, firefighters had finally started to get the blaze under control, and people were being allowed back into communities in the area known as the burn scar. New Mexico officials turned their attention to those who had nothing to return to.

Kelly Hamilton, deputy secretary for the state Department of Homeland Security and Emergency Management, told FEMA in a letter that people were living in their cars, at work and in churches, in campers and even in tents.

He asked FEMA to provide travel trailers or mobile homes. “If the housing situation is not immediately addressed, the survival of each community is bleak,” he wrote.

“If the housing situation is not immediately addressed, the survival of each community is bleak.”

He cited an analysis showing there was just one rental apartment available in Mora and San Miguel counties, the two hardest hit by the fire. He noted that roughly 20% of residents in those counties were below the poverty line and that one-third of Mora County residents were disabled, according to U.S. Census Bureau figures.

It took FEMA a month to approve Hamilton’s request and about two weeks more to tell the public. On Aug. 2, the agency announced it would launch a small housing program, which “will likely entail placing a manufactured home on the resident’s property for the length of time it takes to rebuild.”

But there were strict rules for where those trailers could go. Recipients would need to have electrical service, septic tanks and drinking water close to the housing site. The agency’s draft contract for the housing program specified details down to the width of straps that were required to secure trailers against wind.

Local and state officials and disaster survivors told Source and ProPublica that the utility requirements were unreasonable, especially in this area. It’s common for homes to be heated with wood stoves fed with timber harvested from the surrounding land. Some people didn’t have running water or septic tanks even before the fire. Electrical outages were common in remote areas.

Martinez’s cabin never had running water; he got it from his neighbor’s well. So even if FEMA had offered him a trailer earlier, he would have had to pay thousands of dollars to build a well — if he could’ve found someone to do it.

FEMA is “very efficient in deeming people ineligible.”

“I’m trying to put this diplomatically,” said David Lienemann, spokesperson for New Mexico’s emergency management department. FEMA is “very efficient in deeming people ineligible.”

The effect of those rules is clear. As of April 19, FEMA said 140 households were eligible for trailers, as determined by the agency’s own inspections and policies. Of those, 123 had “voluntarily withdrawn.”

People dropped out because they “opted to live in their damaged homes, located another housing resource or declined all Direct Housing options,” said FEMA spokesperson Angela Byrd in an email. “However, those households remain eligible for the program should their situation change.”

FEMA wouldn’t allow Vicki Garland to connect a trailer to her solar panels, which weren’t touched by the flames. Instead, the agency insisted that she connect to the power grid, which would’ve cost her about $20,000. She’s now moving to the outskirts of Albuquerque, about 140 miles away.

Six individuals and families said they left the program because it would’ve cost too much to hook a trailer up to electricity, restore their wells or meet other utility rules.

Emilio Aragon was living in his office when he was told he was third on the list for a FEMA trailer. After waiting six months, he gave up and spent his retirement savings on a mobile home. He was among six individuals and families who said they were offered housing too late or faced delays that forced them to find housing on their own.

In response to those accounts, FEMA said in a written statement that it must ensure housing is safe and secure. “Generally, this is not a fast process because it requires us to be so thorough and meticulous. Working during the monsoon season meant it took additional time to make sure these sites were safe.”

FEMA has had a hard time getting people into temporary housing quickly after disasters. After Hurricane Ida struck Louisiana in 2021, FEMA said its housing program “is not an immediate solution for a survivor’s interim and longer-term housing needs” because it takes months to get sites ready. The agency praised Louisiana’s decision to launch its own federally funded housing program alongside FEMA’s.

A few months after the storm, The New York Times reported, the state’s program had housed around 1,200 people in about the same time it had taken for FEMA’s program to house 126.

Because FEMA’s housing programs end 18 months after a disaster declaration, every delay runs down the clock. Unless the Hermits Peak housing program is extended, it will expire in November, when the next winter is approaching.

FEMA declined to say whether it would extend the program, saying it would work with the state to meet survivors’ needs.

Wesley Bennett and his wife, JoDean Williams Cooper, said they went through three inspections to see where a trailer could be placed on their property. No spot was suitable, and they were instead offered a site at a mobile home park. Five other individuals and families said they pulled out of the housing program because of the red tape.

FEMA has noted that nine households declined to live in a mobile home park. Several of the trailers it has installed at those sites stand empty.

Some survivors, including Bennett and Cooper, said it wasn’t feasible to live in a trailer park an hour away from the homes they were rebuilding, especially with so many roads washed out by the flooding that followed the fire. They needed to stay on their land to take care of crops and deter theft.

“People who have largely lived in a rural setting are not going to be as comfortable in a trailer park. It’s just their whole way of life,” said Antonia Roybal-Mack, a lawyer who’s from the area and is assisting hundreds of victims in filing administrative claims for damage with the federal government.

“Here’s hoping it’s a paperwork issue”

Erika Larsen and her partner, Tyler White, were living in a camper van after losing their home in the village of San Ignacio when they learned FEMA was offering temporary housing.

Their livelihoods depended on being on their land, they said. Larsen is an herbalist who before the fire made tinctures and elixirs with ambrosia, hops and nettle she grew in gardens dotting the property. White works in construction and gets a lot of her work from neighbors who know where to find her.

Early on, White was feeling optimistic. She posted to a private Facebook group of disaster survivors on Aug. 23, a day after a FEMA inspection.

“Amazingly enough, yesterday we were approved for a trailer to live in. There is only one place to put anything on our property because of flooding. Our well and septic are shot because of fire and floods so we didn’t think we’d qualify. But we did. We should get it in a couple months,” she wrote.

“All this is to say as much as it stinks dealing with FEMA,” she wrote, “as hard of a fight as it can be, you might just get something out of it.”

Two days later, she added something.

Their case manager had “asked us if we wanted to live in a FEMA trailer park. We told him we’d been approved for a trailer at home and he said there was no record of that. Here’s hoping it’s a paperwork issue!”