The Bonneville Power Administration has confirmed Cascade Locks mayor’s concerns about proposed new construction

More, please: Located five miles downriver from Cascade Locks, Bonneville Dam generates electricity to power approximately 900,000 homes. Photo: Kevin Wingert/BPA

By Nathan Gilles, May 3, 2023. In March, Columbia Insight published a lengthy investigative story on a new $100 million data center proposed to be built by a startup company called Roundhouse in the small Columbia River Gorge town of Cascade Locks, Ore. Our reporting addressed many locals’ concerns about the company, its CEO Stephen D. King and its proposed data center.

Among other issues, Columbia Insight discovered that King owed over $1 million to former business partners due a previous troubled business deal in the Gorge.

What Columbia Insight was unable investigate at the time were concerns residents said they had about the data center’s expected energy usage, and statements made by King that local electricity rates would not increase due to the data center’s added electric load.

The most noteworthy Cascade Locks resident to dispute King’s claims has been Cascade Locks Mayor Cathy Fallon.

Fallon has said publicly that the new data center will both raise the cost of electricity for the City of Cascade of Locks and make the city contractually obligated to continue paying that higher cost even if the data center should close its doors and stop consuming electricity.

King has publicly taken issue with these claims.

However, representatives from Bonneville Power Administration (BPA), which provides power to the City of Cascade Locks, have now confirmed to Columbia Insight that BPA does plan to charge the city a higher rate for its electricity due in part to the new data center’s power usage.

BPA representatives also confirmed that as a condition of its contract with BPA, the city will be responsible—at least in the short term—for some, though not all, of the increased costs associated with the data center should the data center close.

Complicating the issue is the fact that even without the data center online and consuming electricity, BPA will be raising the city’s power rates in the upcoming fiscal year starting in October 2023.

According to a recent City of Cascade Locks memo obtained by Columbia Insight, these new increased rates are expected to cost the city an additional $570,000 a year.

And BPA isn’t the only utility raising its rates. Pacific Power and Portland General Electric are also increasing their rates.

However, $570,000 in additional costs pales in comparison to the nearly $5 million in additional costs the City of Cascade Locks will be expected to pay when the data center is fully online, according to estimates made by BPA.

Yet how and if the city’s many electricity customers, including local households, could end up paying for this increase is uncertain.

What is certain is the city is currently exploring the idea of raising its rates on its customers to cover this year’s rate increase with BPA.

What’s also certain is the data center will significantly increase the amount of power consumed in Cascade Locks.

Roughly double power consumption … for starters

The City of Cascade Locks currently provides roughly 4.5 megawatts (MW) of electricity a month to its local businesses and households. In winter, as temperatures drop and furnaces turn on, that number can reach as high as 7 MW, according to numbers provided by the City of Cascade Locks.

When complete, the data center is expected to consume roughly twice as much electricity as the town’s current households and businesses combined.

This power won’t come online all at once, but in phases.

In the first phase, Roundhouse will operate a data center out of the Flex 6 building, an existing Port of Cascade Locks building that now lies empty.

Roundhouse is expected to use 3.6 to 4 MW of electricity a month at Flex 6, according to previous statements made by King.

For phase two of the data center, Roundhouse hopes to build a second facility on a nearby 10-acre empty lot. This facility is expected to need an additional 7.2 MW a month, for a total energy usage of about 10-11 MW, according to previous statements made by King.

Center of attention: The proposed data center would be built in the Flex 6 Building in Cascade Locks, which is currently unoccupied. Photo: Jurgenhessphotography

But Roundhouse’s power consumption might not end there.

At an Oct. 27, 2022, Port of Cascade Locks commission meeting, King told the Port commissioners if the two facilities proved successful, Roundhouse would consider building a third facility for its data center, raising the company’s total electricity consumption to 25-30 MW, according to meeting minutes.

King also told Port commissioners that BPA’s power, which he said was priced at “50% of what it’s worth,” was one major reason Roundhouse was pursuing a data center in the Columbia River Gorge, according to a video recording of the meeting.

The source of this electricity, hydropower, will also help the data center meet industry standards to quality as a “green” data center, according to statements made by King during a March 2023 interview with Columbia Insight.

King did not respond to email and text requests for an interview for this story.

James Longacre, Roundhouse’s chief operating officer and chief engineer, also did not respond to Columbia Insight’s request for an interview.

Mayor vs. King

King has said the data center’s use of electricity would benefit the City of Cascade Locks’ budget.On Feb. 2, the day before Roundhouse and the Port signed a Memorandum of Understanding, King presented a document to the Port that claimed Roundhouse’s direct purchase of electricity from the City of Cascade Locks would increase the city’s power revenues by $1.5 million annually.

Fallon says she has no idea if this number is accurate or not.

“The bottom line is anything that Stephen King says you can’t take it for the truth,” says Fallon. “Some of what he says could be true, but you don’t know because he lacks credibility.”

Looking at numbers: Cascade Locks Mayor Cathy Fallon. Photo: Nathan Gilles

Fallon says King has frequently not answered her questions and has made contradictory statements. Several of these statements she says have to do with the data center’s projected water usage.

As Columbia Insight reported in March, King had originally proposed running the data center using a system that would use “no water,” but later changed the data center’s design to a system that uses “four people’s worth of water” per year, according to statements made by King.

Fallon says King’s past behavior coupled with the data center’s projected power usage makes her wary of the new data center.

“The whole thing is a gamble,” Fallon told Columbia Insight. “I don’t want Cascade Locks holding the bag.”

Fallon has publicly challenged King’s statements about the data center’s power usage.

The two faced off on March 15 when the Port of Cascade Locks and Roundhouse held an open house to discuss the new data center.

The open house was held at the empty Flex 6 building, the proposed site of data center’s first phase.

Flex 6 was built by the Port for a business called The Renewal Workshop, a clothing recycling company. The Renewal Workshop, however, ran into financial problems, leaving Cascade Locks in April 2022 after the company was acquired by a Dutch company.

At the open house, Fallon told the crowd that leasing Flex 6 to a data center involved an even larger risk than having a manufacturing business like the Renewal Project occupy the space.

“The Renewal Project that came in, their power usage wasn’t very much at all,” said Fallon, addressing the crowd, King and members of Roundhouse. “It’s a big difference if a data center comes in and fails, because BPA says our power increases [with the new data center] and once it increases we don’t get to say to the BPA ‘well we’re not using that much power anymore, so we want our old rates.’ It doesn’t work that way.”

King was quick with a rebuttal.

“Your paying rates have nothing to do with our data center,” said King.

“It’s going up. Rates are going up,’” Fallon responded.

“Not due to our usage,” said King. “However, we have said if our particular usage goes up we would cover that. Frankly, I’m not worried because it’s not correct.”

So, who is right?

It depends on how one defines “rates.”

The city’s rates

BPA sells power to the City of Cascade Locks, which operates the local public utility district. The city then sells that electricity to its electricity consumers, including households and businesses.

BPA sells electricity to the city at what is, in effect, a wholesale rate. The city then sells this electricity to its customers at what is, in effect, a retail rate.

Fallon says the “rates” she was referring to are the rates BPA sets for the City of Cascade Locks, not the rates households and businesses pay for their electricity.

The data center’s added electric load means the BPA will charge the City of Cascade Locks a higher rate for its electricity.

The rates that the city charges its customers once it has that electricity might or might not go up due to the data center depending on where the city sets its rates. Fallon says the city is currently taking steps to make sure the rates at which it sells electricity remain affordable.

The City of Cascade Locks, at Fallon’s request, is currently working with an attorney specializing in data centers to ensure that Roundhouse—and not the city’s other electric customers—pay for any cost increases associated with the data center.

“I’ve spoken with other city governments,” says Fallon, “and there are ways that we can structure our rates so that Roundhouse pays for [the cost of] their load and those costs aren’t passed on to the rest of Cascade Locks.”

While Cascade Locks currently charges most households and businesses a flat rate for their electricity, the city is currently developing a special “negotiated rate” for Roundhouse, according to Jordon Bennett, city administrator for the City of Cascade Locks.

“We have never had anything close to this before,” says Bennett. “We have one business [Roundhouse] coming in and essentially asking for double the amount of power the rest of the city uses. They are such a large utility we are looking at doing a negotiated rate.”

BPA rates and load study

By contrast, the rates BPA charges the city are projected to increase.

BPA’s rates are projected to increase starting in October without the data center online, according to the recent City of Cascade Locks memo. But they’re also projected to increase in the years ahead due in part to the data center, according to an electric load study conducted by BPA and obtained by Columbia Insight.

BPA verified the authenticity of the document.

The load study includes several projected future rate scenarios that calculate what the city is likely to pay BPA in the future depending on how much electricity it consumes.

The load study includes three scenarios with the data center’s electric load online and one with it offline.

The offline scenario is called the “Base Case” because it sets a baseline for the other scenarios. The base-case scenario is projected for October 2024.

In the base-case scenario, BPA is expected to charge the City of Cascade Locks $46.58 per megawatt hour (MWh) for its “Total Effective Power Rate,” according to BPA’s load study.

However, with both phases of the data center online, BPA plans to increase the city’s total effective power rate to $57 per MWh, a rate increase of 22.35% above the October 2024 base-case scenario.

Kevin Farleigh, account executive at BPA, confirmed that this increase of 22% is due in part to the data center’s energy usage.

“Yes, they [the data center] would raise the rates at which the city is buying power from us [BPA] by that 22%,” says Farleigh, referring to the load study.

This scenario is projected to start as early as 2025, according to the load study, though Farleigh says 2026 is probably a more accurate date for the rate increase to begin.

Farleigh says any actual rate increase in the future assumes rates stay comparable to what BPA is projecting, adding that these rates could change.

“That forecast could either be too high or too low,” says Farleigh.

“On the hook”

BPA Senior Spokesperson Doug Johnson confirmed the data center’s added electric load will mean BPA will not only charge the City of Cascade Locks a higher rate for its electricity, but also that the city will be required to continue paying BPA at that higher rate even if data center closes.

In practice, this also means the city would be required to cover at least some of costs of the missing electricity consumption should the data center go out of business and stop consuming electricity, according to Johnson.

However, Johnson says, the city wouldn’t have to pay the full amount for data center’s missing load because BPA would sell the unused electricity to other users on the electric grid.

In this scenario, BPA would credit the city for the sold electricity.

Only it’s a little more complicated than that.

Mighty small: About 1,400 people live in Cascade Locks. Photo: City of Cascade Locks

BPA will credit an account regardless of whether it sells the electricity or not. However, BPA is unlikely to credit the full amount owed, according to both Johnson and Farleigh.

Both men confirmed that BPA typically credits unused electricity at a rate that is lower than the rate the original user would have bought the electricity for if the load were still being used. This means should the data center go away, the City of Cascade Locks would most likely owe BPA for some of the data center’s unused electricity.

“Under the current rate structure,” says Johnson, “it [current credit pricing] certainly wouldn’t make them [the City of Cascade Locks] whole [out of debt with BPA], but it would certainly provide a little bit of relief if the [data center’s electric] load evaporated.”

What’s more, Johnson says, if the data center were to go away the city wouldn’t be responsible for these costs indefinitely. That’s because BPA’s contracts are organized in two-year periods.

“If it [the data center and its load] goes away,” says Johnson, “you’re only on the hook for that amount for whatever that proportion of the two years for which the rates are set and then it starts over again.”

The city could also renegotiate its rates with BPA within its two-year contract. Though Johnson says the renegotiation process takes time.

Total costs

Cascade Locks is also projected to have a much larger total electricity bill with the data center online.

The 2024 base-case scenario (in which the data center is not yet online) estimates the city’s “Total Power Charges” will be roughly $1.8 million a year, according to the load study.

With both phases of the data center online in 2025, the city’ total power charges will be roughly $6.6 million a year, according to the load study.

The load study also includes two scenarios in which the data center’s power is phased in during 2024 and 2025. Under these scenarios, BPA plans to sell the city electricity at reduced rates.

However, even with these reduced rates in 2024 and 2025, the city is projected to pay as much as $2.8 and $4.8 million respectively, according to the load study.

Cascade Locks City Administrator Jordon Bennett says these large bills require “responsible” planning on the city’s part.

“Our stance is if it [the data center] happens, great,” says Bennett. “But we as an electrical utility, we are required to sell them power and we are going to do it in a way that makes sure we have enough [electricity] to power the whole city and they’re not taking it all and we’re not left holding the bag.”

Depending on the scenario, says Bennett, the city might or might not have the money in reserve to pay BPA what it owes should the data center go out of business.

“We do have money in reserve, though not in that amount,” says Bennett, referring to projections in BPA’s load study.

If the city were to come up short, Bennett says it would consider raising rates on its other electricity customers to cover the bill.

However, Bennett says regardless of the data center’s projected energy usage, the city will be raising its electric rates to cover the $570,000 in additional costs BPA is expected to charge the city for electricity in the upcoming fiscal year.

And this is what the city is currently exploring doing, according to the recent memo, which was written by Bennett.

The memo reads: “To ensure the City Light department can stay solvent we must look at rate changes.” Asked to explain if this language meant the city was going to raise rates on its customers, Bennett was straightforward.

“Yes, we’re going to have to [raise rates],” says Bennett. “How exactly that math is going to pencil out, I don’t know. But that’s kind of how it works. We have to pass it on [costs].

New substation, “overgrown paperweight”

But there’s another problem associated with the data center’s projected energy consumption: Cascade Locks currently doesn’t have the electric infrastructure to support both phases of the project.

The city currently has the infrastructure to accommodate Roundhouse’s 4 MW usage at Flex 6, but it wouldn’t be able to accommodate the full 11 MW—let alone 25-30 MW—without a new substation.

“There is no way they [Roundhouse] can do what they are calling their phase two without an electrical system update,” says Bennett. “There is no way.”

The city’s current substation, called the Pyramid substation, can accommodate about 14 MW.

With the Flex 6 building’s 4 MW online, the substation will run at roughly 70% capacity, according to Bennett.

Bennett says the city is hoping to add an additional 35 MW by building a new substation.

The new substation plan was proposed in 2017 when the Eagle Creek Fire raised concerns that the city’s electric infrastructure was vulnerable to wildfires, according to Bennett.

The city has since acquired a $2.4 million grant from the U.S. Economic Development Administration to buy the new substation and purchase the land for the new substation from BPA.

But as part of its deal with BPA, the City of Cascade Locks is required to buy a smaller 6 MW substation in order to buy the land for the larger 35 MW substation. This smaller 6 MW substation won’t be used, according to Bennett.

“It’s essentially an overgrown paperweight at this point. I mean it works, but at 6 megawatts it doesn’t do much,” says Bennett.

Bennett says the deal with BPA isn’t finalized yet.

Possible limits to growth

Brad Lorang, vice president of the Port commission and a former mayor of Cascade Locks, says he sees another potential downside to the data center’s heavy power usage.

Lorang says having one company consuming such a large amount of electricity could limit local economic development by limiting the Port’s ability to attract other businesses, especially if Roundhouse builds its facility out to 25-30 MW.

“I do not want us to get into a situation where some other business would want to come along, and we’re already maxed out on our ability to provide power,” says Lorang.

Columbia crossing: The Bridge of the Gods is owned and operated by the Port of Cascade Locks. Photo: Di Manickam/Unsplash

In February, when the five-member Port of Cascade Locks Commission signed a memorandum of understanding with Roundhouse to approve the data center, Lorang, who has been a vocal critic of the data center, cast the lone dissenting vote.

The MOU was expected to lead to Roundhouse signing a 25-year lease with the Port. The signing of the lease is behind schedule, according to Lorang.

Roundhouse was expected to occupy the Flex 6 building starting in April. That did not happen. Lorang says the company’s move-in date was moved to May 1, but that hasn’t happened either.

Lorang says the Port has had other offers to both lease and buy Flex 6 from the Port, which he says would help lower the Port’s debt burden.

Lying empty, Flex 6 has cost the Port roughly $300,000 in accrued interest on the $6 million loan the Port took out to build the facility, according to Lorang.

But Lorang says he’s concerned that the data center could limit local development in another way as well. Lorang says local economic development is limited due to the town’s small size and the Columbia River Gorge National Scenic Area that surrounds it.

He says one of his biggest concerns with the proposed deal with Roundhouse is the company’s plans to build out the nearby 10-acre lot, which Lorang says not only ties up that land but would discourage other types of development, such as a resort, which he says would provide a greater positive economic impact for Cascade Locks than a data center.

“It’s beautiful property,” says Lorang. “It’s right on the river. In my mind, a data center is not the best use for that property. And we really have one shot at this, because once you start putting in a large industrial [data center] it will become hard to attract other types of businesses. A resort is not going to want to locate next to a huge warehouse.”

Lorang says he also has his concerns about both King and Roundhouse. While many members of Roundhouse have experience with data centers, King does not.

Lorang says this fact and information revealed by Columbia Insight about King’s past business dealings have made him even more critical of the proposed data center.

King’s past

As Columbia Insight reported in March, King ended up owing over $1 million to former business partners when King failed to complete a previous project for a proposed aquaponics facility in Hood River County. This failed business deal led to legal action being taken against King and a separate investigation by the State of Oregon into potential fraud and violations of securities laws on King’s part.

Columbia Insight has since obtained through a public records request a partially redacted investigation memorandum from the Oregon Department of Consumer and Business Services Division of Financial Regulation concerning King and the Hood River project.

The memorandum confirms many details in Columbia Insight’s reporting, including how a single investor lost over $880,000 to King when King attempted to purchase land for the aquaponics facility using her money.

The memorandum confirms that a nonrefundable $590,000 was paid to the site’s Hood River County property owners as earnest money to purchase the land.

The investigation tracked the rest of the money through six bank accounts tied to six different companies associated with King. The memorandum concludes the rest of the investor’s money went to business expenses and salaries.

The “most concerning expenses,” according to the memorandum, were “the large salaries” of $180,000 a year [paid to King and other business partners]. The memorandum concluded these large salaries were “not in itself fraud.”

The investigation was dropped. The aquaponics project was never built.

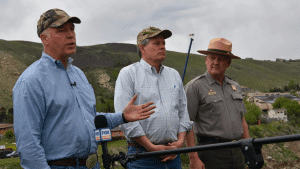

Stating the case: Stephen D. King explaining the proposed data center at a March 10 open house inside the Flex 6 building. Photo: Nathan Gilles

Lorang says he thinks it’s “unlikely” that King will find the financing to complete the data center.

“At this point [the data center is] not moving forward,” says Lorang. “I think his [King’s] history may give people some concerns about loaning him [King] the money.”

However, Lorang says he’s still concerned that the deal might be approved by the Port only to have the project stall or fail.

“The more information that we got, that only further confirmed my fears in his [King’s] ability to pull this off,” says Lorang. “I don’t want somebody to get something half done and then bail out.”

Fallon was even more critical.

“Again, the whole thing is a gamble. And I don’t gamble with other people’s lives and money. I just don’t,” says Fallon.

Whether the deal with Roundhouse goes through or not could come down to the leadership of Port President Jess Groves, who is the subject of an ongoing effort to have him recalled by voters.

Groves was “unavailable” for an interview with Columbia Insight, but agreed to answer questions in writing, according to an email sent by Jeremiah Blue, the Port’s interim general manager.

Groves has not yet replied to our questions.