When disasters are deemed too small, rural Mississippi struggles to recover

Under a mystic blend of pink lightning and green sky, Victoria Jackson called her daughter in a panic, warning her of the news: A tornado was on a path towards Rolling Fork.

Her daughter was working that March night at Chuck’s Dairy Bar, a staple of the small, south Delta town. Along with some customers, Jackson’s daughter, Natasha, nestled into one of the coolers in the restaurant.

Hours later, once the storm blew by, Jackson headed to find her daughter, navigating through debris. She found Natasha shaking, in tears. While the tornado tore the rest of Chuck’s into shreds, the cooler and those inside it were safe.

“I thank God that I called her and told her to get down,” Jackson told Mississippi Today.

The tornado killed 14 people in Sharkey County, and left Rolling Fork with little resemblance of its prior self. While the Jacksons didn’t lose anyone or anything that night, the reason they were in Rolling Fork in the first place is because, three months prior, they lost everything.

The first tornado the Jacksons survived wiped away their homes last December, tearing up a trailer park where they lived in Anguilla. Victoria, her sister, aunt, cousin and everyone in their families lost their homes, among five total that were destroyed. About 20 members of the family had to relocate a few miles down Highway 61 to a motel in Rolling Fork. Many of them, including Victoria, are still there.

As is often the case for rural disaster survivors, the damages they endured were too small to trigger crucial federal aid. Victoria didn’t have home insurance and lost her job after the storm. Now, nearly six months later, her family hasn’t seen a cent of government disaster aid, and are instead counting on donations to put them in a real home again.

Disaster recovery is already an often difficult and drawn-out process. But for rural, poor towns like Anguilla, a town of 496 people, it’s even tougher.

When people think about disaster recovery, they often think of “FEMA” – the Federal Emergency Management Agency, the national hub of government disaster aid. In reality, though, a vast majority of the country’s disasters don’t receive any FEMA money. They’re what experts call “undeclared” events.

“If you were to aggregate all the losses tied to undeclared disasters, they actually are more costly than typically declared disasters,” said Gavin Smith, a professor of Landscape Architecture and Environmental Planning at North Carolina State University who has helped lead recovery efforts in multiple states.

In Mississippi, nearly a thousand homes have been damaged in undeclared disasters in just the last two years, state records show.

FEMA aid, which comes when the president signs a disaster declaration, is reserved for the larger disasters that leave states needing additional resources. But when a disaster doesn’t meet that threshold, most states, including Mississippi, can’t replicate the kinds of services FEMA can offer.

The programs states receive after a federal declaration include: paying for public infrastructure repairs, putting people in temporary housing, sending direct payments to survivors, expanding safety net programs like food stamps and uninsurance benefits, among others.

Since more often than not, FEMA money is unavailable, many disaster survivors rely on their home insurance to pay for repairs.

But low-income, uninsured families like the Jacksons have to instead depend on the slow, complex network of volunteers and charities. Nonprofits and national religious groups help struggling communities recover all over the country, collecting donations to help rebuild homes, and providing otherwise costly labor for free. But that process takes time.

“If they’re back and recovered within six months, that is like warp speed for these organizations,” said Michelle Annette Meyer, the director of the Hazard Reduction & Recovery Center at Texas A&M University. “At best, they’re looking at a year-long process to get the donations in, confirm the paperwork, get the volunteers and get the materials donated.”

For Sharkey County, where Anguilla and Rolling Fork are, the nonprofit Delta Force handles disaster recovery, finding new homes for survivors after undeclared events. Delta Force’s chairman, Martha Bray, wouldn’t comment on specific cases for privacy reasons, only saying that they’re waiting for enough donations to come in to buy new mobile homes for the Jacksons.

“It’s going to be a long process, that’s all we hear,” Victoria Jackson said.

Last December, just before Christmas and after the tornado destroyed her home, Jackson lost her retail job at a local shop. She said her boss didn’t let her come back despite giving her time off after the storm, and then listed her as having quit, which blocked her from unemployment benefits.

Now, she’s sharing a two-bed room with her husband and six kids at the Rolling Fork Motel.

Jackson said she received $2,500 in initial donations from local churches and charities. But expenses like food, gas, laundry, and taking care of her children quickly dried that money up. Since her daughter Natasha lost her job at Chuck’s Dairy Bar, the family’s relying on her husband’s truck-driving job to keep them afloat.

After the December tornado, Anguilla Mayor Jan Pearson reached out to state and U.S. representatives, hoping that they could appeal for government assistance. The traces of the tornado were widespread in the small town, damaging businesses and even blowing the roof off the town’s middle school, forcing students to relocate.

“I wrote all of them a letter,” Pearson said. “However, to no avail. We did not get anything.”

County officials, Pearson said, told her the damages didn’t meet the threshold for federal assistance.

“I keep hearing we didn’t meet the threshold,” she said. “Well I asked somebody, ‘Will you tell me what the threshold is?’ No one could tell me what the threshold is.”

For Individual Assistance, the FEMA program that includes housing and other direct support for survivors, there is no set threshold, officials told Mississippi Today.

“It is kind of subjective,” FEMA spokesperson Mike Wade said.

FEMA weighs several factors, such as the degree of damages and the amount of uninsured losses, when deciding if a declaration is justified. The agency categorizes damages into several categories, ranging from “affected” to “destroyed.”

But to local and state officials, FEMA’s criteria is unclear.

In the summer of 2021, for instance, heavy rain flooded 284 homes in the Delta. While local officials pleaded for federal support, the state informed them that not enough of the homes received “major damage,” which FEMA defines as needing “extensive repairs.”

Last March, 33 tornadoes touched down in Mississippi, destroying 42 homes across a dozen counties. The state applied for a federal declaration, but was denied.

While there’s no set threshold, the Mississippi Emergency Management Agency estimated that at least 50 homes need major damage to earn a federal declaration.

But the damages from undeclared disasters in just the last couple years dwarf that number.

Since 2021, 982 homes in the state received some damage from an undeclared natural disaster, according to records from MEMA; 81 of those homes were completely destroyed, and another 203 received major damage.

“When you look at only one of (the undeclared disasters), the damage may be relatively small,” said Andrew Rumbach, a senior fellow at the Urban Institute whose research focuses on rural recovery efforts. “But when you add all those up across the state, it actually cumulatively could be much more important than some of those big events that do get that support.”

Anguilla has just 250 households, according to the Census. Sharkey County Supervisor Jesse Mason, who represents Anguilla, wondered how such a small place could reach the amount of damages that FEMA looks for.

“I don’t know what the magic number is,” Mason said. “I guess maybe it had to tear the whole town up.”

Rural areas have an especially hard time getting FEMA disaster aid, experts say. Mississippi was the fourth most rural state according to a 2010 Census survey, the latest with such data. Sharkey County, home to 3,488 people, is the second least populated county in the state. Neighboring Issaquena County is the first.

“The more rural you are and the more scattered your population and assets are, sometimes those kind of events are the ones that slip under the radar compared to the events where there’s media, for example, to immediately cover it, or there’s political pressure to immediately make declarations,” Rumbach said.

Mississippi has a program that sends money to counties after undeclared disasters. The Disaster Assistance Repair Program, or DARP, works with local nonprofits, and sends up to $250,000 for materials to rebuild homes. Meyer, the Texas A&M professor, said that’s more than what most states do after undeclared events.

Since 2018, DARP has helped rebuild 850 homes in 22 counties. But Sharkey County hasn’t applied for DARP funds to help the Anguilla survivors, and officials couldn't be reached to explain why.

Every county in the state has emergency management officials. But in Sharkey County, there are only two such employees, and both work part-time. Counties with lower tax bases and less capacity to do damage assessments struggle to make the case for disaster declarations, Rumbach said.

One of those two employees, Natalie Perkins, also runs the local weekly newspaper. After the Rolling Fork disaster, which President Joe Biden approved for federal aid, Perkins saw firsthand the difference a declaration makes.

“When you have a declared disaster, everyone comes out of the woodwork to help,” she said. “But when you have an undeclared (event), you don’t get the attention, you don’t get the donations, you don’t get the federal and state funding that you do in a declared disaster. That’s just the bottom line.”

On the morning of Mar. 29, five days after the tornado in Rolling Fork, which also damaged parts of Anguilla, Mayor Pearson scrambled to help FEMA officials set up a booth outside of the town hall.

Pearson sat down with Mississippi Today to talk about the December tornado, the one that displaced the Jacksons. She emphasized that she didn’t want to take away attention from what happened in Rolling Fork. But she couldn’t hold back frustration over the lack of help Victoria Jackson and her family received.

“These people just three months ago lost their homes,” the mayor said. “I can’t equate Rolling Fork with Anguilla. But come on now, people are people, humans are humans. The (Jacksons) left Anguilla and came to Rolling Fork. Now a tornado hit Rolling Fork. These people don’t have anything, and you’re telling them they can’t qualify (for FEMA aid)?”

At the motel, the Jacksons accused the owner of poor treatment, saying he recently raised their weekly rent to $400, and charges extra to wash their sheets. When reached for comment, the motel staff said the owner was out of the country and couldn’t comment. Meanwhile, the Jacksons don’t know how much longer they’ll be able to afford the room.

That Wednesday, while federal officials were in Anguilla, Victoria tried to apply for FEMA aid. They called back later, she said, telling her she’d been denied. While the agency won’t comment on specific cases, FEMA confirmed that aid wasn’t available for people in her situation.

“We just need the help that they’re giving other people,” Jackson said, wondering why she and her family had been left out. “Anguilla is Sharkey County, Rolling Fork is Sharkey County, so all this should be combined together, right? Help for everybody, right?”

The post When disasters are deemed too small, rural Mississippi struggles to recover appeared first on Mississippi Today.

Toxic Nuclear Waste is Piling up in the U.S. Where’s the Deposit?

Decades on end and after spending billions, the U.S. still has no strategy to permanently deposit its highly radioactive nuclear waste.

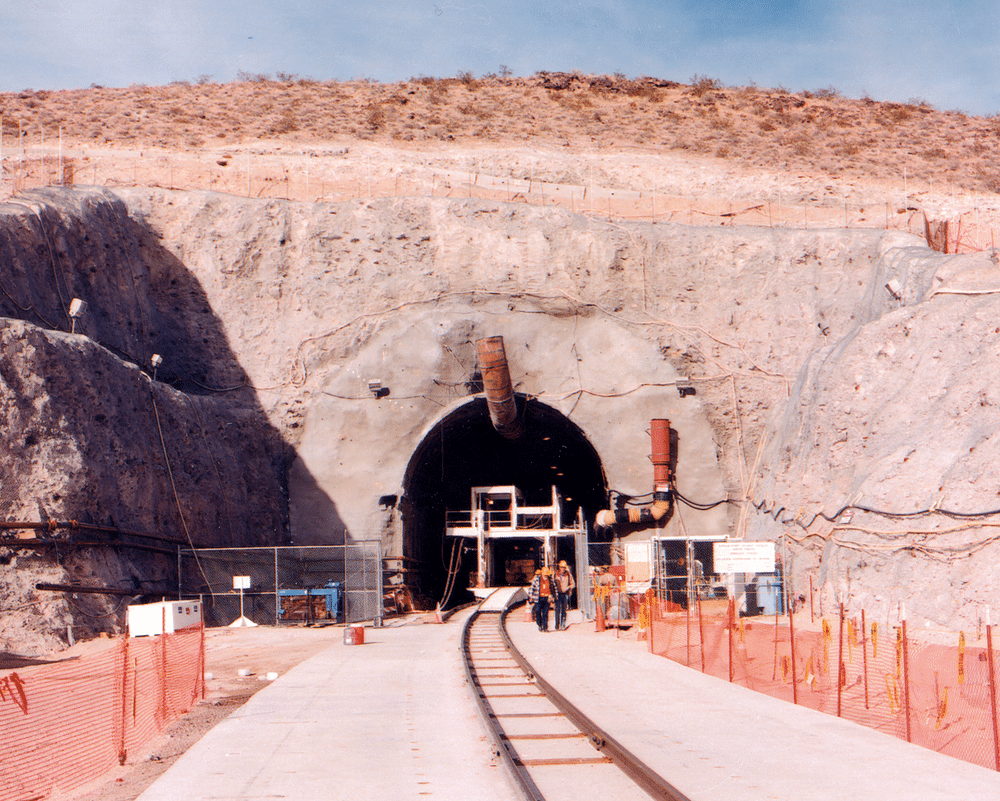

Some 90 miles northwest of Las Vegas, deep in Southern Nevada, lies a multibillion-dollar hole.

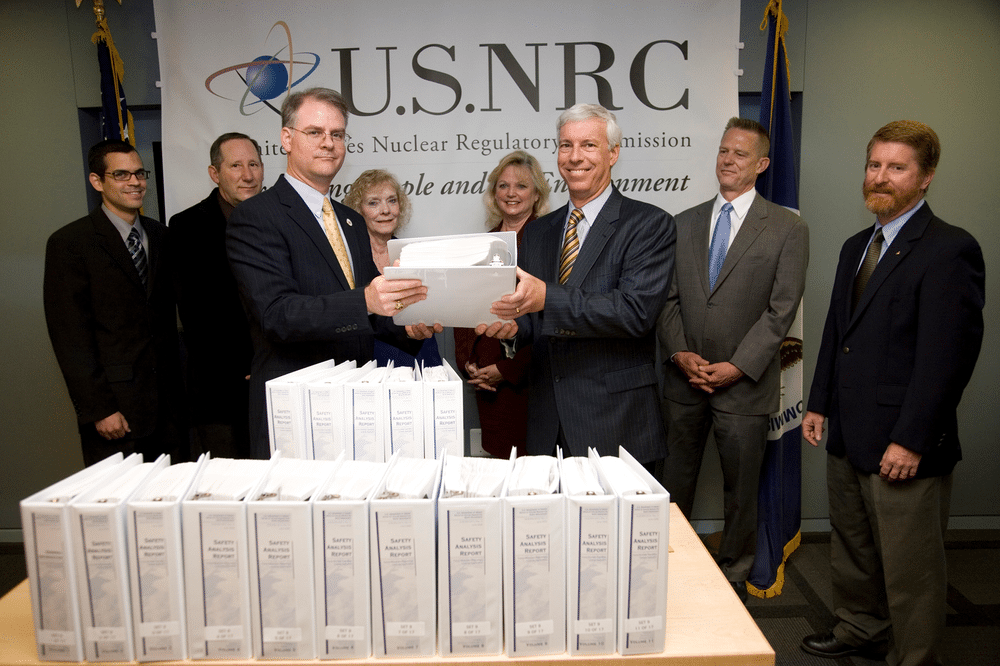

Twenty years ago, the George W. Bush government formally chose the dry, arid landscape to build a tunnel complex. The Yucca Mountain project would have been the place to deposit up to 70,000, or more than 75% of the 90,000-and-growing metric tons of highly radioactive spent nuclear fuel coming from commercial reactors in the country. Yet, almost from the onset, locals and politicians resisted the project because of what it would entail: a constant stream of nuclear waste coming into Nevada from where they are currently stored, hundreds of miles away. (Only one of the 75 sites with currently operating nuclear plants are even located within the Mountain States, an eight-state region including Nevada that spans nearly 900 thousand square miles across the Rockies.) And so, between 2009 and 2010, the Obama administration kept its campaign promise and stopped the project.

“I just didn’t like it. It was too much danger in nuclear radiation leaks. And, it just didn’t

make sense. Then, the safety aspects […] I don’t know quite how to put it, it just didn’t make sense to transport that kind of stuff through this area when the areas that were keeping it couldn’t just keep it in their own backyard.”

“I don’t know quite how to put it, it just didn’t make sense to transport that kind of stuff through this area when the areas that were keeping it couldn’t just keep it in their own backyard.”

Barbara and Ken Dugan lived near Crescent Valley, Nevada, back in 2011. The events of the Fukushima meltdown were fresh on everyone’s minds. They were speaking to Abby Johnson, then the Nuclear Waste Advisor for Eureka County who worked on collecting opinions from local communities after the Yucca Mountain project shut down.

Another decade on, the U.S. still has no solid solution for its nuclear waste. Nuclear power leaves a small carbon footprint compared to other types of energy. Still, the question of managing its waste is complicated. Nuclear waste can stay radioactive from a few hours to hundreds of thousands of years. Therefore, scientists and the industry agree that the best long-term solution is to bury the waste underground in large, heavily engineered repositories while it remains unsafe. But building these sites seems to be a difficult endeavour, and the U.S. isn’t the only country struggling to get it done.

Out of the 32 nations operating nuclear reactors today, only Finland is close to finishing a deposit. Countries like the U.K., where the first nuclear power station in the world to produce electricity for domestic use was built, are struggling with finding a site in the first place. According to a 2018 report, “Reset of America’s Nuclear Waste and Management”, prepared by the Stanford University Center for International Security and Cooperation (CISAC) and the George Washington University Elliott School of International Affairs, for 50 years, governments and committees worldwide have launched at least 24 campaigns to create underground repositories. Still, in only five of these, committees managed to choose a site to work with. And so, the question arises: how come nations capable of technological breakthroughs like sending humans to space can’t seem to find a place for their radioactive waste?

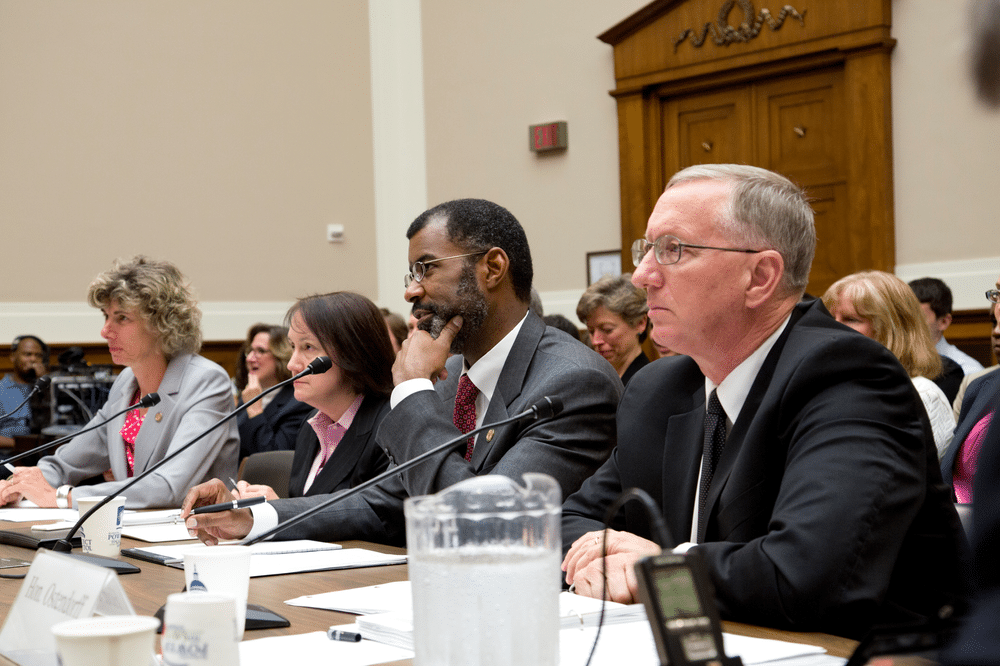

A lack of policymaking consistency hasn’t helped the nuclear waste cause on American soil; that’s what Rodney Ewing — co-director of CISAC and the former chairman of the U.S. Nuclear Waste Technical Review Board who reviewed the Department of Energy’s efforts to manage and dispose of nuclear waste during the Obama administration— thinks is part of the answer.

According to him, the Nuclear Waste Policy Act of 1982, which represented the path forward in managing nuclear waste in the U.S., kept changing throughout the 80s and 90s. For example, congressional amendments in 1987 specified Yucca Mountain as the sole candidate site instead of allowing for multiple candidate sites to be considered. More recently, the ongoing chaos of re-funding and re-defunding Yucca Mountain by the Trump administration made it challenging to convince anyone. “The more you keep changing direction, or changing the rules, the less trust you can count on from candidate communities. The lower the probability that you will be successful”, he adds.

“The more you keep changing direction, or changing the rules, the less trust you can count on from candidate communities. The lower the probability that you will be successful”

Ewing believes the country needs cohesiveness and an independent organization to move forward — perhaps in a manner similar to the Tennessee Valley Authority, as recommended by the Blue Ribbon Commission on America’s Nuclear Future in 2012, or a non-profit, nuclear utility-owned implementing corporation, as suggested in the 2018 CISAC report.“In the past, Yucca Mountain suffered from the fact that the Department of Energy wears many hats, everything from fossil fuels, solar, nuclear, nuclear weapons, and so on. Somehow, in that broad context, developing a geologic repository was low on the [priority] list.”

Another hurdle that has made this project an uphill battle in the U.S. is the bungling of public engagement. Unlike the NIMBY battles unfolding across the country that are snarling public transit, solar farms, or less-carbon-intensive forms of housing, Yucca Mountain falls on Western Shoshone territory, where Indigenous residents are still dealing with the consequences of resource extraction and nuclear testing by the federal government without their full consent, leading to their sustained opposition to the project. This is not to mention other local fears about the toxicity levels of a deposit, the permanence of the project (radiation levels were expected to be regulated for the next million years), and the impact it might have on property and land values. “The state of Nevada has not been willing to accept this possibility [of a nuclear waste deposit]. And so, the federal government has dealt with a state that doesn’t want the repository. That’s a social issue”, says Ewing.

To minimize public outcry, it’s key that a site is decided voluntarily: a community states they’d accept a nuclear waste site in their area, and only after initial conversations should projects start. This is one of the reasons Finland ended up being successful with their project when the local authority voted overwhelmingly in favour. Yet, according to Pasi Tuohimaa, the Communications Manager at Posiva — the company responsible for managing radioactive waste in Finland —there’s more to the whole process. Culture takes center stage when choosing a site. He told The Xylom that communities where nuclear power plants had been active for decades tend to be more accepting of hosting a nuclear waste site. “If you have a strong nuclear identity, if you have a site where there’s been a power plant for 40 years or 45 years, then people know […] a lot about radiation, they know about radiation safety”. He also mentions that Finns, in general, want to solve the issue of nuclear waste rapidly not to harm future generations. “The Finnish people believe that if our generation has created [nuclear waste], then it’s our generation’s duty to take care of the waste and not leave it for the solidarity of future generations”, he adds.

“The Finnish people believe that if our generation has created [nuclear waste], then it’s our generation’s duty to take care of the waste and not leave it for the solidarity of future generations”

Other nations like Canada and the U.K. are now moving forward with strategies in which communities host deep geological repositories voluntarily. The Biden administration is also moving forward with a consent-based siting approach; however, the aim is to make storage sites, not geological repositories15,18. This means waste will be stored for some time but not in the long term: a permit issued by the Nuclear Regulatory Commission in May to build and operate one such facility in southeastern New Mexico is valid for only 40 years. Ewing is skeptical of such an approach.“I call it indefinite storage. And I would say indefinite surface storage of highly radioactive waste […] is not a very attractive solution. It’s not a solution.”

Building deep geological repositories is crucial to safely deposit nuclear waste despite being a tall task. As other western Nations inch closer to having their own sites, it remains to be seen whether the U.S. has the will to drive a much-needed site forward, or whether it is content with kicking the can down the road — until the country buckles under this mountain of a problem.

History Repeats: Forged by Fire, Red Hook Has Endured Dozens of Major Blazes Over the Past Century; Rhinebeck, Too

Who is ‘Held’ of Held v. State of Montana?

This article is part of a series on the youth-led constitutional climate change lawsuit Held v. Montana, which goes to trial in Helena on June 12. The rest of the series can be read at mtclimatecase.flatheadbeacon.com. This project is produced by the Flathead Beacon newsroom, in collaboration with Montana Free Press, and is supported by the MIT Environmental Solutions Journalism Fellowship.

Rikki Held’s last name has been referenced in legal briefs, news articles and water cooler conversations for two years now, since the court case Held v. State of Montana was filed in Montana’s First Judicial District Court. Held was one of 16 youth plaintiffs who filed the 2020 lawsuit against several Montana government agencies, and its governor, alleging that the implementation of two energy-related policies is an infringement of the youths’ constitutional right to a clean and healthful environment. Since she was the only plaintiff of age when it was filed, it’s her name that will be forever attached to the decision made in the landmark case.

Held was brought to the legal table by a meandering path that runs through the heart of her family’s ranch. Held grew up on a 7,000-acre cattle ranch and saw the destruction of the land and her family’s livelihood caused by the changing climate — an experience she feels can be understood by the rural state’s ranching and farming communities.

“I think that ranchers see it in a different way, ranchers are on the ground every day,” Held said. “Maybe they aren’t having as many conversations about climate change necessarily, but they are seeing these changes with wildfires and are worried about the daily impacts of hay prices going up because of drought and losing cattle from water variability or fires.”

Between growing up on a ranch and a chance encounter with the world of scientific inquiry at a young age, Held charted a unique path to the courtroom. And while Held didn’t set out to become a climate activist, she felt compelled to act on behalf of her younger peers. Those who are too young to vote on the actions of the government look at the world through a different lens than their older counterparts, she says.

“As youth, we are exposed to a lot of knowledge about climate change. We can’t keep passing it on to the next generation when we’re being told about all the impacts that are already happening,” Held said. “In some ways, our generation feels a lot of pressure, kind of a burden, to make something happen because it’s our lives that are at risk.”

Before it was a legal reference, Rikki Held’s name was first published in the acknowledgments of a 2015 peer-reviewed paper in the scientific journal GeoResJ titled “Preserving geomorphic data records of flood disturbances.” Though Held was in middle school at the time, she is credited with helping U.S. Geological Survey (USGS) researchers survey cross sections of Montana’s Powder River, one of the longest undammed waterways in the West, which happens to pass through her family’s 7,000-acre ranch.

The Powder River begins in the Bighorn Mountains of Wyoming and flows north through Montana before joining the Yellowstone River between Miles City and Glendive. With no man-made modifications along the route other than some diversions to irrigate farmlands, Powder River provides a lengthy, natural, outdoor laboratory — a scientist’s dream. A study on the river that began in the 1970s has quantified the natural erosion, transport and deposition of sediments throughout the riverbed, and mapped changes to the river’s channel with specific focus on years of high flood or periods following nearby wildfires. Researchers have established 24 survey sites along a 57-mile stretch of the Powder River, several of which are accessed through the Held family ranch.

Several scientific papers have come out of the study over the years. One documented the aftereffects of a major flood event in 1978 where as much as 65 feet eroded from sections of the river bank. Regular follow-up studies characterized sediment composition, erosion patterns and plant distribution along the river.

“Even when I was little I would go out with [the researchers] during surveys, just following them around and learning from them,” Held said, adding that she “got kind of caught up” in the science, which later led to internships and ultimately the mention in the 2015 paper. “I think that really got me interested in science, I was able to connect it back to my ranch, my home.”

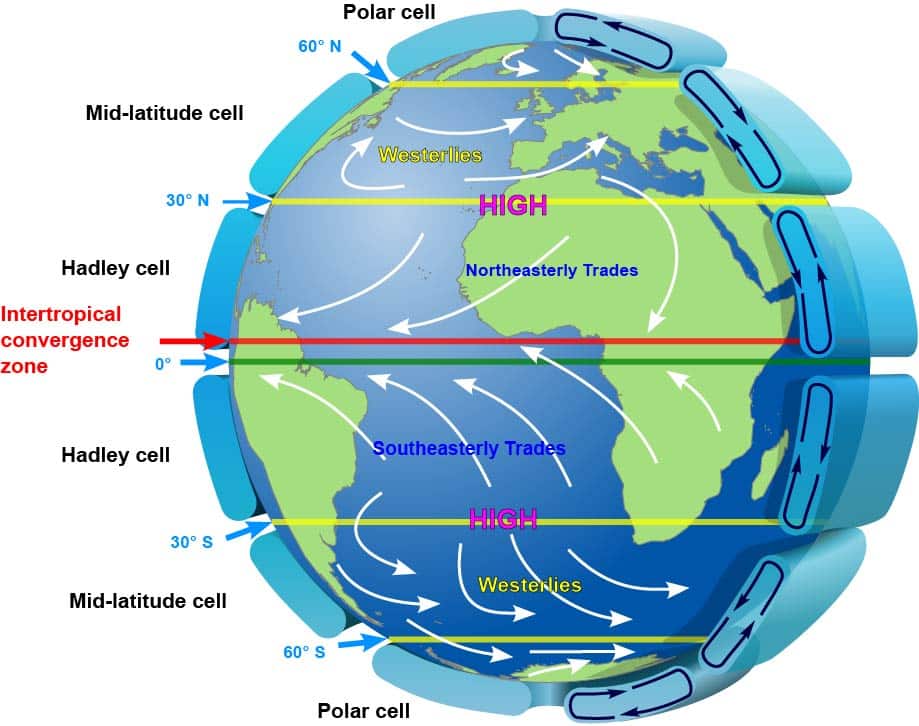

Throughout high school, Held gravitated toward the hard sciences. “I remember a wind pattern diagram with Hadley cells, and I just thought that was fascinating how things could be explained,” she said. “I got really interested in environmental science that way and learned about climate change in high school. I just knew that this is a really serious issue that we need to focus on.”

Held, now 22, graduated this spring from Colorado College with a degree in environmental science and is figuring out how to use her aptitude for environmental research to carve out a career path. Speaking about a recent NASA-funded study she contributed to, Held grew visibly excited as she described her work on “combining ecology and geomorphology to map out invasive Russian olive species.” She said she’s considering future studies in climatology or hydrology, something “about Earth processes where I can bring it back to the people and use science to help them.”

While Held was learning to survey stream widths and how Hadley cells circulate tropical air around the globe, she was also witnessing the effects of extreme weather events on her family’s livelihood. The complaint states that in 2007, following several years of drought in southeastern Montana, the Powder River dried up, eliminating the water source for the ranch’s crops and livestock. A decade later, an early spring thaw flooded the river basin, nearly reaching Held’s house and eroding several feet of riverbank. Increased risks of major flooding events, such as the 2022 floods that damaged an entrance road to Yellowstone National Park, have been linked to global warming. One study published using the Powder River data also cites climate change as a contributing cause for the river’s changing migration rate over time.

The Held family has lost cattle to flooding events, an economic hardship for any ranch. On the elementally opposite side of the extreme weather spectrum, the Helds also lost a great number of animals in 2012 to starvation following a wildfire that burned through acres of grazing land. The fire took out miles of powerlines in the area, leaving the ranch without electricity for weeks. During another spate of nearby fires in 2021, Held recalls ash falling from the sky, dusting the ground for days, and local schools being set up as shelters for families that had to evacuate their homes. The wildfire smoke, along with a record-breaking string of triple-digit days that summer, didn’t keep Held inside — there was ranch work that couldn’t wait.

“When you’re in the moment, you have to just keep going with daily life, you have to do everything you can to keep up with the business or keep your livestock as safe as you can and figure out issues like how to get them water,” Held said. “It’s hard to think about it more broadly in terms of climate change … but from studying this, I know that we need to make some big systematic changes in what we’re doing to not continue down the route we’re taking.”

The increased effects on her family’s ranching lifestyle, along with her growing interest in studying environmental science in college, led Held to reach out to Our Children’s Trust when she heard about the potential lawsuit.

“When I was first learning about climate change in high school, I saw it as something on the other side of the world, like polar bears and ice melting or the coastlines with sea level rise,” Held said. “Living in the U.S., in a landlocked place, I didn’t really think about how it affected me, even though I’d seen these changes while I was growing up.”

“Being part of this case, it’s been nice to put my own story into the broader climate change narrative and make the connections through science and observation of how my home plays into it,” she said. “Montana is a big emitter of fossil fuels and is contributing to climate change. I know it’s a broader global issue, but you can’t not take responsibility.”

Held doesn’t know whether she’d consider taking over the family ranch, saying she’s “unsure what the future will be there.” It’s a sentiment about the viability of the industry she thinks is shared by many farmers and ranchers in the state — indeed it’s her lived experience on the family ranch that she thinks will allow the lawsuit to resonate with a greater portion of Montanans who may not as readily engage in discussions of climate change

Across the state, though, Held believes that Montana is still a place where residents value their neighbors and the land and resources they’re entrusted, making it a unique place for this lawsuit to play out.

“Those values could play into this conversation and make a change,” she said. “It’s important that this case is happening here.”

The post Who is ‘Held’ of Held v. State of Montana? appeared first on Montana Free Press.

Hay – yes, hay – is sucking the Colorado River dry

With path cleared for the Mountain Valley Pipeline, opponents weigh next steps

With President Joe Biden’s signature fresh on legislation that would expedite the completion of the Mountain Valley Pipeline, pipeline officials aim to have it up and running by year’s end, while the project’s opponents are considering their options.

The Fiscal Responsibility Act, which Biden signed Saturday, suspends the U.S. debt ceiling for nearly two years. It also includes a provision specific to the Mountain Valley Pipeline: It authorizes all remaining permits and other approvals necessary for the natural gas pipeline’s construction and operation, and it shields the project from further legal challenges by removing the jurisdiction of courts to review such approvals.

Initially planned for completion in 2018, construction on the 303-mile pipeline through Virginia and West Virginia has effectively been halted since 2021 by federal and state permitting delays and by legal battles brought by landowners, environmentalists and others who have challenged the pipeline’s acquisition of private property through eminent domain and its impact on forests, streams, wetlands and endangered species, among other legal grounds.

“The MVP project has gone through more environmental review and scrutiny than any natural gas pipeline project in U.S. history, having been issued the same state and federal authorizations two and three times, only to have those authorizations be routinely challenged and vacated in court,” Thomas Karam, chairman and CEO of Equitrans Midstream, the pipeline’s operator, said in a news release after Biden signed the bill.

The $6.6 billion, 42-inch pipeline is set to start in northwestern West Virginia and proceed into Virginia, where it will pass through Giles, Craig, Montgomery, Roanoke and Franklin counties before connecting to a compressor station in Pittsylvania County. Pipeline officials say the project is more than 90% complete, though opponents dispute that claim.

Pipeline supporters say the project is an important source of secure, domestic, lower-carbon energy that meets a demand for natural gas. U.S. Sen. Joe Manchin, D-West Virginia, who was the primary driver of the pipeline provision’s inclusion in the debt-limit deal, called it a “critical energy security project” and said it “opens up markets for our natural resources, giving us untold new revenue sources and developing industries that our grandchildren and future generations will benefit from.”

Opponents say the project is unnecessary and harmful to the environment, both in terms of future greenhouse-gas emissions and the impact of its construction — and some say they aren’t ready to give up the fight.

“Even if some of these permits are issued and initially shielded from judicial review, that’s not necessarily the end of the line,” said Jason Rylander, senior attorney with the Center for Biological Diversity, which advocates for species protection and other environmental causes. “The pipeline still has to cross some of the most difficult terrain along the route, through the Jefferson National Forest and other areas, and there will be opportunities to hold them accountable for the damage they are continuing to do.”

Beyond watching the pipeline’s progress to see what comes next, it’s unclear what specific further options might be available to pipeline opponents.

After Thursday’s Senate vote, the Protect Our Water, Heritage, Rights — or POWHR — coalition released a statement from Denali Nalamalapu, its communications director, saying, “Our global movement to stop the Mountain Valley Pipeline is stronger than ever.

“While we are outraged and devastated in this unprecedented moment, we will never stop fighting this unfinished, unnecessary, and unwanted project. Our hearts are broken but our bonds are strong,” the statement said.

Asked about specific next steps, Nalamalapu replied in an email: “We don’t have clear answers at the moment but we likely will in the coming days/weeks.

“Right now we are focusing on mobilizing in front of the White House on June 8th to respond to this unprecedented decision and hold Biden accountable to his broken climate promises,” Nalamalapu wrote, referring to a protest, sponsored by People vs. Fossil Fuels, scheduled in front of the White House from 2 to 4 p.m. Thursday.

Tom Cormons, executive director of the grassroots environmental protection group Appalachian Voices, said in a statement that “the fight is not over.”

“Defeating this unnecessary and ill-conceived project that has already degraded water quality across two states and would contribute significantly to the climate crisis if it is completed and brought into service is a top priority,” Cormons said.

Preserve Bent Mountain, which is a local chapter of the Blue Ridge Environmental Defense League and part of the POWHR coalition, released a statement saying, “It is not yet clear whether the stench of the MVP/debt limit deal will surpass legal scrutiny.”

“While repulsed at this Dirty Deal, we will go forward — as we have since the inception of this destructive boondoggle, with all regulatory and legal challenges available. We will not be governed by the gas industry,” the group said in a statement sent by member Roberta Bondurant, a Roanoke County resident.

One possible path forward for opponents could be contesting the pipeline provision itself.

“Clearly the bill, or what will soon be the law, forecloses most court actions on the pipeline. But the one thing that is left is a possible challenge to the law itself, presumably on constitutional grounds,” said David Sligh, conservation director of Wild Virginia, an environmental advocacy nonprofit.

U.S. Sen. Tim Kaine, D-Virginia, suggested the same during a conference call with reporters last week ahead of the Senate’s vote on the bill. Senators also voted 30-69 to defeat an amendment brought by Kaine that would have removed the Mountain Valley Pipeline provision from the debt-limit legislation.

“I would think that frankly the only option under this bill is not to challenge any aspect of the pipeline but to challenge, did Congress have the legal ability to do what it just did?” Kaine said. “That would be the only remaining challenge.

“Now of course at the end of the day, once the pipeline’s underway, there may be provisions where people can say, ‘Wait a minute, you didn’t do the restoration on my land right,’” Kaine said. “We haven’t eliminated that down the road, if the pipeline violates state laws, because in both West Virginia and Virginia the construction of the pipeline has violated water quality standards and state agencies have been able to challenge them. They still have to comply with state laws.”

Kaine noted that the authors of the Mountain Valley Pipeline provision appear to have anticipated a potential legal challenge against the provision itself: The bill specifies that the U.S. Court of Appeals for the D.C. Circuit “shall have original and exclusive jurisdiction over any claim alleging the invalidity of this section or that an action is beyond the scope of authority conferred by this section.”

Sligh, of Wild Virginia, said environmental advocates will continue monitoring Mountain Valley Pipeline’s work on the ground, ensuring that any citizen complaints are funneled to the appropriate governmental agencies and following up to verify that regulatory rules are enforced.

“I have looked at thousands — thousands — of the inspection reports that the state of Virginia has done … and they have done a pretty good job of being out there and documenting some of the problems, a lot of the problems. But Virginia has not done what it needs to do to stop them once it finds them,” he said.

Beyond that monitoring work, Sligh said, “I think everybody is quickly trying to assess what else is possible.”

The post With path cleared for the Mountain Valley Pipeline, opponents weigh next steps appeared first on Cardinal News.

The Battle for Clean Energy in Coal Country

Montana has a long history of making money by extracting and exporting its natural resources, namely coal. State politicians and Montana’s largest electricity utility company seem set on keeping it that way.

Reveal’s Jonathan Jones travels to the town of Colstrip in the southeastern part of the state. It is home to one of the largest coal seams in the country – and one of the largest coal-fired power plants in the West. He learns that the state has signed off on a massive expansion of the coal mine that feeds the plant and that Montana’s single largest power company, NorthWestern Energy, has expanded its stake in the plant, even though it’s the single biggest emitter of greenhouse gas in Montana. Jones speaks with Colstrip’s mayor about the importance of coal mining to the local community. He also speaks to local ranchers and a tribal official who’ve been working for generations to protect the water and land from coal development.

Jones follows the money to the state’s capital, where lawmakers have passed one of the most extreme laws to keep the state from addressing climate change. He meets with plaintiffs involved in a first-of-its-kind youth-led lawsuit who are suing Montana for violating their constitutional right to a “clean and healthful environment.” Jones dives into lobbying records behind a flurry of bills that are keeping the state reliant on fossil fuels. He also finds that NorthWestern is planning to build a new methane gas plant on the banks of the Yellowstone River, and the company is being met with resistance from people who live near the site and from state courts.

Finally, Jones visits the state’s largest wind farm and speaks with a renewable energy expert, who says Montana can close its coal plants, never build a new gas plant and transition to 100% clean energy while reducing electricity costs for consumers. He also speaks with NorthWestern’s CEO and looks at other coal communities in transition.

Dig Deeper

Read: Gianforte signs bill banning state agencies from analyzing climate impacts (Montana Free Press)

Read: Affordable and Reliable Decarbonization Pathways for Montana (Vibrant Clean Energy study for 350 Montana)

Read: The Coal Cost Crossover 3.0 (Energy Innovation Policy & Technology)

Read: Net Zero by 2050 (NorthWestern Energy)

Listen: Colstrip’s Next Chapter (Shared State podcast from the Montana Free Press, Montana Public Radio and Yellowstone Public Radio)

Watch: “Cowboy Poets,” a 1988 film featuring Wally McRae, a cowboy poet and conservationist in southeastern Montana.

Watch: What the Hell is Going On With the Colstrip Plant? (Montana Environmental Information Center)

Credits

Reporter: Jonathan Jones | Producer: Stephen Smith | Editor: Jenny Casas with help from Kate Howard | Additional reporting and research: Amanda Eggert | Fact checker: Nikki Frick | Production manager: Steven Rascón | Original score and sound design: Jim Briggs and Fernando Arruda | Digital producer: Nikki Frick | Episode art: Stephen Smith | Interim executive producers: Taki Telonidis and Brett Myers | Host: Al Letson

Reported in partnership with the Montana Free Press. Special thanks to reporter Mara Silvers and editor Brad Tyer of the Montana Free Press and Yellowstone Public Radio.

Transcript

Al Letson: From the Center for Investigative Reporting and PRX, this is Reveal. I’m Al Letson. The local coal industry has always been a villain in William Walksalong’s life.

William Walksalong: They’re like a monster, and its teetering, ready to fall over. And that, I want to be part of the effort to cut its throat and let it bleed out and let it go away.

Al Letson: William grew up on the northern Cheyenne Indian Reservation in southeast Montana. It’s near one of the largest coal seams in the country and one of the largest coal fire power plants in the west. He remembers when they started building it when he was in high school in the seventies.

William Walksalong: Oh, I remember distinctly all kinds of strange people from all over the country, construction workers. They’d blast those power plants to test them and you could drown everything out even in the classroom, kind of startle you when they were starting those big power plants up.

Al Letson: The power plant is in a town called Colstrip, and William was against it from the beginning. But when the construction was done, a lot of people from his community went to work there.

William Walksalong: I had adults and high school students telling me and my brother we were traitors, that we should go back to Colstrip and dig coal.

Al Letson: William never worked for the power plant or the coal mine that fed it. In the nineties, he became the vice president of the tribe at a time when there was a push to expand coal mining into the reservation.

William Walksalong:

They were trying to get rid of our Indian nation as a obstacle or a barrier to unfettered energy development, including undermining our sovereignty, promising economic self-sufficiency, at the cost of our historical cultural sites. It was just a total shakedown of our way of life.

Al Letson: For the last three decades, William has done everything he can as a tribal administrator to keep coal mining off the reservation. And most recently, he was a part of an ongoing lawsuit against the Biden administration’s decision to permit coal leasing on public lands. Coal is, by far, the single biggest contributor to climate change. In 2022, global coal production rose above 8 billion metric tons, its highest level in history.

William Walksalong: I remember growing up. We had deeper snow, better runoff, and I’ve never seen so much drought in my life, and I’ve been alive for about almost… Well, I’m 64 years old, and I’ve never seen drought last that long. [inaudible] Creek dried up that one year, never seen that in my lifetime, and it’s due to climate change.

Al Letson: More and more states are shifting their energy consumption away from coal, but Montana is running in the opposite direction. The state is expanding coal mining and the legislature has been passing laws to prop up the fossil fuel industry.

Interviewees: Coal really is our ace in the hole. We just want to keep producing coal and bring money into the coffers.

And we’ll help encourage that industry to stay in the business of generating electricity.

We have a third of the nation’s coal, which greatly supports the state of Montana.

It’s good for Montanans and it’s good for business.

William Walksalong: They must live on a different planet. I don’t understand that. Well, I know the Republican super majority, they want to make it a clear path, easier path for energy development, dirty energy, I guess, coal and gas plants.

Al Letson: Montana is a place with some of the most extreme laws to prevent the state from addressing climate change. There’s also a powerful fossil fuel lobby and it’s a state with a lot of potential to completely shift to clean renewable energy. Reveal’s Jonathan Jones went to the Colstrip power plant, the one that was built when William was in high school and where the fight over its future has implications for the entire planet.

Jonathan Jones: I’m standing next to a big coal field. There’s a big black ridge of exposed coal, and then there are these big earth moving machines that are pushing the coal. This is the Rosebud coal mine. It’s right outside the town of Colstrip in southeastern Montana and one of the largest strip mines in North America.

Jonathan Jones:

Bulldozers and large trucks that are bringing massive amounts of coal in from the coal mine to this big pile of coal that they’re then going to put on a conveyor belt. And the conveyor belt is like this long sort of khaki colored centipede that carries the coal from here to the power plant.

Jonathan Jones:

The conveyor belt feeds coal directly to the Colstrip power plant that towers over the town.

Jonathan Jones: It’s a massive structure with four smoke stacks, two of which are active, two of which are quiet, and then there are two big cooling towers with billowing vapor coming out of it.

Jonathan Jones: Along with that vapor, the plant also puts out more than 10 million metric tons of carbon dioxide each year. It emits more greenhouse gas than any other single source in Montana, making it one of the biggest producers of CO2 in the western United States. The electricity made here has powered homes and buildings across the state and the Pacific Northwest since the 1970s.

Jonathan Jones: It’s coal fire power plants like this that’s provided most of our electricity for generations. But that’s changing now with the shifting energy market as more and more states pass legislation to wean themselves off coal.

Jonathan Jones: But not Montana. The Rosebud strip mine is expanding and one of the owners of the Colstrip power plant plans to keep burning coal until at least 2042 and people in the town want it that way.

Jonathan Jones: There are very few retail stores here. Right next to me is the Energy Employees Credit Union and outside there are two signs, one of which says “Coal keeps the doors open,” and the other one says “Coal keeps the lights on.” It’s almost hard to go one block here without seeing some sort of sign promoting coal, defending coal, and reminding people of coal’s importance to the energy sector and of course to Colstrip.

John Williams: My name is John Williams. I’m the mayor of the City of Colstrip. Everything here is either coal or power production as a result of coal.

Jonathan Jones: John Williams first moved here in 1971 when there were only a few hundred people in town.

John Williams: Colstrip came from the fact that this was a large strip of coal here. The story is that it was misspelled by the federal government when they put in the post office down here and that’s the name, and it stuck with it. C-O-L-S-T-R-I-P rather than C-O-A-L. That’s the story.

Jonathan Jones:

Mayor Williams says he was one of the first two employees who oversaw the construction of the power plant. He essentially built the town and helped incorporate it as a city in the nineties. As I drive around, you can’t help but see a lot of the signs that say “Coal keeps the lights on,” “Coal keeps the doors open.” Can you talk a little bit about that?

John Williams: It’s happened because of the threat against coal, the war against coal. I mean billions of dollars within our state have been created as a result of the mining of coal and we get a lot of benefit as a result of coal, jobs, taxes.

Jonathan Jones: Together, the coal mine and the power plant are the two largest employers in the Colstrip area. The jobs and the tax revenue support a first class public school system, a nine hole golf course, medical services, a park system, and a median household income that’s 35% higher than the state average.

John Williams: Don’t kill the goose that laid the golden egg, so that’s my take on that. Right or wrong, that’s how I feel.

Jonathan Jones: So obviously this is a community as you’ve said that is extremely dependent on one natural resource, coal.

John Williams: Coal.

Jonathan Jones: And we’ve talked about sort of its positive aspects, but how has this created some challenges for the community?

John Williams: Well, part of the challenges are that we’re considered to be a one horse town, one industry town. And there’s also, we have a number of companies, the Pacific Northwest companies are making decisions or having decisions made for them that to remove themselves from coal.

Jonathan Jones: What he’s referring to is that for decades, Colstrip’s biggest customer for electricity was the Pacific Northwest. The Colstrip power plant is owned by six power companies, the majority of which are based in Oregon and Washington, and now they want out of Colstrip for what boils down to two main reasons. First, those companies are facing new climate laws requiring them to stop using coal power. Second, they say it’s too expensive to run the coal fire power plant. But there’s one main stakeholder staying put in Colstrip and buying out the other’s shares, NorthWestern Energy. It is the single largest electricity provider in Montana.

Brian Bird: I may be the only CEO in the utility industry adding coal to his portfolios.

Jonathan Jones: That’s NorthWestern CEO, Brian Bird at a meeting of state lawmakers and other officials in Montana’s capital. He’s announcing that NorthWestern is buying out another owner in Colstrip and for an unbeatable price, nothing.

Brian Bird: So understand why are we doing this, we’re doing this for our customers and our communities in Montana. And by the way, we’re doing it for three reasons, reliability, affordability, and sustainability.

Jonathan Jones: After the announcement, environmental groups blasted NorthWestern’s new Colstrip deal. They said it had nothing to do with reliability, affordability, or sustainability.

Anne Hedges: So NorthWestern wants that plant to continue to operate, not because it’s this great resource that it can’t possibly do without, it’s because that’s a lot of money and they don’t want to lose it.

Jonathan Jones: Anne Hedges is co-director of the Montana Environmental Information Center. It’s one of the state’s leading environmental groups. Her organization has legally challenged Colstrip stakeholders over a dozen times over pollution, rate increases, and mining expansions.

Anne Hedges: NorthWestern doesn’t give a hoot about its customers. It is more concerned about its executive salaries and bonuses and its shareholders than it is about the people who pay the bills.

Jonathan Jones: The company operates as a monopoly in Montana. It profits from generating electricity and charging people for it, and it also makes money by recouping the costs of its investments from its customers. So buying up shares and owning a bigger portion of the Colstrip power plant means more money for NorthWestern. This is how electric utilities operate in most states.

John Oliver: Our main story tonight, utilities, specifically electric utilities.

Jonathan Jones: John Oliver explained it this way on his show Last Week Tonight.

John Oliver: When they build something, a piece of physical infrastructure, they’re allowed to then pass along that cost to you through your bill, plus an additional percentage that they get to keep as profit, usually around 10%, and this creates a clear incentive. The bigger the project like a power plant, the more profit they make.

Jonathan Jones: John Oliver uses this analogy. It’s like a waiter in a restaurant where there’s a guaranteed tip. The more money that is spent on the meal, the more the waiter is going to make. NorthWestern first bought its stake in Colstrip in 2007 and paid around 187 million for it. But then the state approved the company’s request to value their assets in the power plant at 407 million, more than double what NorthWestern paid for it. And since utilities get to make back their expenses plus another eight to 10% profit, NorthWestern gets to pass the cost of the plant onto its electricity customers. In other words…

Anne Hedges: As long as that plant operates for the life of the plant, which was expected to be about 2042, NorthWestern will continue to collect from its customers. That’s a lot of money over time.

Jonathan Jones: A lot of money and a lot of consequences for the environment. Here’s Anne speaking on a recent webinar called What the Hell Is Going on with the Colstrip Plant.

Anne Hedges: Eight to 10 million tons of greenhouse gases a year being released from that facility. If we can’t solve a problem of one single plant like Colstrip and get it on a path towards closure and replacement, then we simply can’t solve our climate problem. I mean, it’s that simple.

Terry Punt: Girls and boys, [inaudible]…

Jonathan Jones: About an hour’s drive south of Colstrip Rancher, Jeanie Alderson and her husband Terry call out to their cows. Well,

Jeanie Alderson: We have about 50 mother cows and then we have yearlings, two year olds and a three year olds. We butcher them about three years old and so they just get fat on… We feed them through the winter and then in the summer they’ll go out on grass.

Jonathan Jones: Jeanie’s a fourth generation rancher. Her family’s run cattle here since the 1880s.

Jeanie Alderson: My dad’s family came from the deep south. My great-great granddad was from Alderson, West Virginia, and he was a Baptist minister. He was an abolitionist, so he had to leave the town and they went to Texas and then they came up from Texas to Montana.

Jonathan Jones: Jeanie’s family came up for the grasslands and the water. It’s why they’re still here today. She worries about the impact that coal has on the land. Toxic waste from the mine and the power plant has already harmed the water, the springs, wells, and creeks that ranchers and farmers depend on.

Jeanie Alderson: When you mine coal and you process it through the power plants, what’s left is the ash. So what they’ve done is to store this ash, they’ve been stored in these ponds, and it is getting into the groundwater. I mean the ranchers that are around Colstrip, it’s very scary for them.

Jonathan Jones: According to the State Department of Environmental Quality, the coal ash ponds associated with the power plant have been leaking since their inception. Elevated levels of toxic chemicals have been found in the groundwater. Colstrip residents have to get their drinking water pumped in from the Yellowstone River 30 miles away.

Jeanie Alderson: Ranching right now is hard enough, really hard to make enough money to stay in business. Since 1980, something like 40% of ranchers in this country have gone out of business and no one is really talking about that. Any other industry had we had that kind of loss, you would see it in the news more. And so we already are stressed to try and keep our ranches together.

Jonathan Jones: The Alderson Family Ranch has had to adapt to the changing market. Faced with relentless pressure from large scale beef packers offering lower prices, Jeanie and her family got creative. They invested in a herd of Wagyu cattle, a Japanese cow that produces one of the most expensive cuts of beef.

Jeanie Alderson: They don’t look like the kind of animals that most ranchers are used to, especially most ranchers in this part of the country.

Jonathan Jones: Other ranchers in the area have also adapted, but Jeanie’s worried that most people in southeastern Montana aren’t planning for a future that doesn’t rely on coal.

Jeanie Alderson: There’s so much potential here, but the leadership in the community, the mayor, the others, they’re so tied to the energy company, and I kind of feel like our leaders are just still thinking that they’re going to just keep going with coal.

Jonathan Jones: And in Helena, state lawmakers say their intention is to do just that.

Al Letson: Coming up.

Jason Small: Coal in Montana’s no different than potatoes in Ireland. I mean, that’s something we got and we’ve got it in spades and that’s our great equalizer, right?

Al Letson: Jonathan heads to Montana’s capital to meet with lawmakers behind the state’s coal expansion. That’s next on Reveal. From the Center for Investigative Reporting and PRX, this is Reveal. I’m Al Letson.

Wally McRae: My family’s been in this corner of southeastern Montana for over a hundred years. We celebrated our centennial year in 1986.

Al Letson: Wally McRae is a third generation rancher. His family has raised cattle and sheep in the Colstrip area since the 1800s. He’s a cowboy poet known for his writing about life in rural Montana.

Wally McRae: Cowboys have probably always been kind of popular, kind of a hero figure and maybe we fit in that. And so if people can get inside of that life through meter and rhyme, it’s got a combination of appeals.

Al Letson: This tape is from a 1988 film by Kim Shelton called Cowboy Poets. The film is from another time, but echoes many of the issues Montana ranching communities still wrestle with today. Here, Wally is describing a major theme of his poetry.

Wally McRae: Because one of the largest strip mines in the United States is in my backyard, I have written several poems about the effect that coal oriented industrialization has upon the cowboy culture.

Al Letson: One of his poems is called The Lease Hound. It describes a coal mining agent visiting a local ranch.

Wally McRae: I’ve come to lease your land for coal was how he launched his spiel. He’d been given an authority, the grand generous deal. The nation needs the coal, he said, as I am sure you know. We need more power every year to make our nation grow. And it’s the patriotic duty of each American to help to get the coal mine and expedite our plan. Now, you may not like strip mining and tearing up the earth, but it’s your duty, isn’t it?

Jeanie Alderson: Land men would go to people in that big boom time in the early seventies, the way my mom described it, and they would say, “Everybody else around you has sold out, why don’t you sign here? There’s nothing you can do.”

Al Letson: Rancher, Jeanie Alderson’s mom, Caroline was a contemporary of Wally’s. She was also hearing from speculators in the mid seventies.

Jeanie Alderson: When you’re told that your patriotic duty is to step aside so they can mine this coal underneath you, it’s insulting, it’s infuriating.

Al Letson: The speculators were there because of a report. The North Central power study published by the federal government in 1971. It designated southeast Montana as “a national sacrifice area for energy production.”

Jeanie Alderson: You know, eastern Montana, this kind of dry area anyway, who’s out there anyway, who really cares? Let’s just turn it into the boiler room of the nation.

Al Letson: The plan proposed building 42 coal fire power plants, half of them in and around Colstrip.

Wally McRae:

They didn’t treat us well, they lied and they pitted one neighbor against another and it wasn’t a pretty sight and it offended us, it really did.

Al Letson: Montana has a long history of making money by extracting its natural resources, namely copper and coal. But Caroline, Wally, and other local ranchers didn’t want to be part of that legacy.

Jeanie Alderson: And my mom and other ranchers, they could right away see that the cost was going to be their land and water and their communities, and they were trying desperately to hold onto that.

Al Letson: Together, they organized the Northern Plains Resource Council, a grassroots movement to protect the land in rural Montana from industrial development.

Wally McRae: I think a lot of people assume that any sort of opposition to coal oriented industrialization was based purely on environmental grounds. I think that our concerns were more cultural or social and finally, long-term economic. I mean, hell, we’ve been here a hundred years, are we going to be able to be here a hundred years from now?

Al Letson: Other environmental groups followed. They held teach-ins, stage protests, and met with lawmakers. Their actions led the state to rewriting its constitution in 1972, producing what has been called one of the most progressive constitutions in the United States. It includes language to protect the public’s right to a “clean and healthful environment in Montana for present and future generations.” Today, a group of Montanans say that right is under attack and it’s coming from inside the state house. Reveal’s Jonathan Jones went to the state capitol in Helena to find out why.

Jonathan Jones: In the rotunda of Montana’s state capitol building in Helena, 14 year old Mica Kantor is practicing his speech.

Mica Kantor: I love animals. My favorite animal’s a pika. Unfortunately, they will be one of the first North American animals to go extinct because of climate change. It scares me to think that I will be-

Jonathan Jones: Moments later, Mica is called to join a small group behind a podium.

Interviewees: Let’s get started. Welcome everyone to the people’s house. Welcome everyone.

Jonathan Jones: Hundreds of people are gathered to hear what they have to say.

Interviewees: Welcome everyone to the rally to defend Montana’s constitution.

Jonathan Jones: Mica gets up to speak.

Mica Kantor: I’m not old enough to vote, so sometimes it is hard for me to feel like my voice is being heard.

Jonathan Jones:

Mica stands out. Not just because he’s one of the youngest people here, but because he’s one of 16 young people suing the state over its fossil fuel energy policies. They argue state officials are violating their constitutional right to a healthful environment. The clause, put into the state constitution decades ago, thanks to environmental activists like Wally and Jeanie’s mom, Caroline.

Mica Kantor: Despite knowing about climate change and its detrimental effects for decades, the state of Montana has decided to ignore it for profit. But we have to ask ourselves if it is worth it. Is it worth it to lose the things we love? Is it worth it to lose the places that we relish? Is it worth it all in order for more profit?

Jonathan Jones: At age four, Mica started worrying about the future of the world’s glaciers. At nine, wildfire and smoke forced him to stay inside for six weeks and made him sick with headaches and eye irritation. At 11, a forest fire broke out about a mile from his home. Mica wrote letters to elected officials asking them to act on the changing climate. He got back a few automated responses. And so when his mom heard about an environmental lawsuit that needed young people to join and asked Mica if he was interested, it was an easy choice.

Mica Kantor: We’ll be the ones to have to live with the effects of climate change more than anybody else, so it’s really important for me to do this.

Jonathan Jones:

The youth-led climate trial is the first of its kind in US history and it’s set to begin this summer on June 12th. Just upstairs from the rally are the offices of the lawmakers whose actions are part of the youth climate lawsuit. Tell me who you are and what you do.

Steve Fitzpatrick: Steve Fitzpatrick, senator from Great Falls, Montana, and I am the Republican senate majority leader.

Jonathan Jones: Senator Fitzpatrick is a lawyer and one of the most powerful political figures in the state. Fossil fuel companies are also some of his biggest campaign contributors. There’s this big rally at the Rotunda noon today over this youth climate lawsuit. What is your reaction to the lawsuit?

Steve Fitzpatrick: [inaudible] I don’t know anything about it. I’ve never read any of the pleadings. I mean, it’s kind of hard for me to offer a comment on a lawsuit where I haven’t even-

Jonathan Jones: But you’re a lawyer and you’re getting sued by the youth of Montana over the state’s climate policy, isn’t it in your interest to know what’s going on?

Steve Fitzpatrick: The state of Montana gets sued all the time, so I don’t… I’m a state legislator, I’m not the attorney general’s office. I don’t go read every lawsuit that gets filed.

Jonathan Jones: Fitzpatrick was elected to the state house in 2010 and then to the senate in 2016. He’s the son of John Fitzpatrick, a former lobbyist for NorthWestern Energy, who is now a state representative. For the past several years, Senator Fitzpatrick has been pushing legislation to make sure the coal fired power plant in Colstrip stays open.

Steve Fitzpatrick: The way I look at that is that we’ve got a resource, we have an asset in the state of Montana, and I don’t think it ought to be destroyed. We need coal and we need energy that’s reliable and useful.

Jonathan Jones: In 2021, when the Colstrip power plant owners based in the Pacific Northwest tried to pull out, Senator Fitzpatrick introduced a series of bills to keep them from leaving. One bill that passed imposed a $100,000 fine for every day they didn’t pay their share of the operating costs.

Steve Fitzpatrick: To have somebody from another state reach into our state and tell us what we’re supposed to do with facilities and plants in our state, yeah, that’s frustrating.

Jonathan Jones: The bills were declared unconstitutional by the courts in October 2022, but that hasn’t discouraged Senator Fitzpatrick and other lawmakers from fighting to ensure the state’s continued reliance on fossil fuels. During the 2023 legislative session, Republicans passed a flurry of these kinds of bills. There was a bill to limit environmental lawsuits over fossil fuel projects, a bill to add a hefty tax for charging electric vehicles, a bill to allow coal mining expansions with limited review, and a bill to weaken water quality protections for coal mines. All of these proposals were signed by the governor and became law.

Jason Small: Mr. Chair, members of the [inaudible] for your consideration.

Jonathan Jones: And then, there was Senate Bill 228.

Jason Small: Basically, this bill preemptively stops any locality from banning fossil fuels and the tools, appliances, or equipment that utilize it.

Jonathan Jones: Senate Bill 228 became law too, making it illegal for local governments to take action to limit fossil fuels in their cities and towns. Senator Jason Small was its primary sponsor.

Jason Small: Coal and Montana is no different than potatoes in Ireland. I mean, that’s something we got and we’ve got it in spades and that’s our great equalizer, right?

Jonathan Jones: Senator Small is from the Colstrip area and a member of the Northern Cheyenne tribe. When he’s not at the state house, he works at the power plant as a boiler maker.

Jason Small: There’s nothing in the state financially that coal doesn’t touch. That’s something even some of the most remote places in the state, there’s some mines there, and those mines keep everybody living a good lifestyle. They’re educating kids. We sprinkle coal dust all over the state.

Jonathan Jones: He scoffed at the notion that the coal industry’s days are numbered.

Jason Small: Oh hell no, coal’s not dead. There isn’t that much reliable power out there and reliable power you’re going to get is from gas. It’s from propane natural gas, methane, it’s from coal. Those are the ones that are always going to be there when you need them.

Jonathan Jones: If there’s one company that seems to benefit the most from these kinds of policies, it’s NorthWestern Energy, the largest single provider of electricity in Montana. The company finances a small army of lobbyists every legislative session. In 2023, NorthWestern lobbied for bills to weaken oversight of coal mining expansions, bills increasing taxes on electric vehicles, and bills restricting solar energy.

News Anchor: NorthWestern Energy is planning to build a new 250 million natural gas plant in Laurel.

Jonathan Jones: The company also supported a bill that allows state regulators to approve big new capital projects like building a new power plant without having to demonstrate it’s actually the best deal for Montanans. And NorthWestern supported that bill while it was building a brand new methane gas plant. The new plant started construction in 2022 and they built it on the banks of the Yellowstone River in Steve Krum’s family’s backyard.

Steve Krum: We’re just south of Yellowstone River, just south of the plant location currently being built by Northwest Energy. I just don’t understand why you’d build a plant like this here.

Jonathan Jones: Steve is a retired oil refinery worker who’s lived in the area his whole life. He wasn’t the only one upset about the plant. Other local residents and environmental groups opposed it since it was first announced in 2021. They say NorthWestern started building before getting the proper zoning permits.

Steve Krum: This thing was being pushed as quickly and as fast as it can. They had no concern for the people here whatsoever. They had zero community meetings to get the people on board, the neighbors that live right next to them.

Jonathan Jones: The new gas plant is projected to emit more than 769,000 tons of greenhouse gases a year. That’s equivalent to the annual emissions of nearly 170,000 cars. Concerned for his community, Steve became part of a lawsuit launched by the Sierra Club and the Montana Environmental Information Center. The suit claims the state unlawfully granted NorthWestern a permit to build the gas plant because it failed to do an adequate environmental review.

Steve Krum: We all know that we got climate issues, we know that. They’re using this as a step to quick money because it’s the most expensive way other than coal to fire a generating plant to get the biggest return they can to their stockholders.

Jonathan Jones: This spring, judge Michael Moses ruled in the plaintiff’s favor. He ordered NorthWestern to halt construction of the gas plant. The plant has been sitting half constructed for months. This win was one of many for environmental groups filing suits against the state for permitting fossil fuel expansions. The judge’s ruling riled Montana’s Republican lawmakers.

Steve Fitzpatrick: So what the judge did, I think was outrageous. It flies in the face of law. It was probably one of the more atrocious pieces of judicial activism I’ve ever seen and we’ve seen a lot of bad decisions out of this judge.

Jonathan Jones: That’s Senator Fitzpatrick again, speaking on the floor of the Montana Senate this April. A few weeks after the ruling, the Republican super majority suspended its own rules to introduce a controversial new bill at the last minute.

Steve Fitzpatrick: This decision by the judge, it threatens every individual project in the state of Montana. This could be refineries, this could be mines, this could be anybody with an air quality permit, and we all know that each individual project is never going to change the temperature of the earth.

Jonathan Jones: The ruling and the lawsuit over the new gas plant were all about how the state failed to assess the environmental impacts including greenhouse gas emissions, so the new bill would prevent state agencies from considering the potential impact of climate change altogether.

Interviewee: Senator Small.

Jason Small: Yes, thank you, Mr. President. House bill 971 makes it clear that unless and until Montana policymakers enact laws to regulate carbon, a procedural review does not include a climate analysis.

Jonathan Jones: In other words, House bill 971 explicitly prohibits all state agencies from considering climate change and greenhouse gas emissions when reviewing projects that could harm the environment.

Jason Small: We’re not going to allow endless litigation to stop projects and industry in the state of Montana.

Jonathan Jones: More than a thousand people submitted comments with the vast majority in opposition to the bill and more than 60 people testified against it.

Steve Krum:

My name is Steve Krum, K-R-U-M. I live in Laurel, Montana and I’m opposed to HB 971.

Interviewees: Are we willing to sacrifice our environment to support corporate profits?

I’m an engineer and a parent and I speak for all the children who aren’t born yet and all the ones who don’t have a voice yet. Please oppose this bill.

My future and the generations to come after me will be significantly affected.

Think of the legacy you will be leaving our grandchildren.

Jonathan Jones: Nationally, the bill is considered one of the most extreme legislative actions to keep regulators from addressing climate change. After it passed, largely along party lines, it was signed into law by Republican governor Greg Gianforte. Two days later, attorneys for the state cited it when asking a judge to dismiss the youth-led climate lawsuit. The judge declined and ordered the attorneys to prepare for trial.

Al Letson: Coming up, Jonathan kicks the tires on the idea that there’s nothing more reliable, affordable, or sustainable than coal power.

Anne Hedges: How much does wind cost for fuel? Nothing. How much does solar cost for fuel? Nothing. Coal is not cheaper, not on any calculus that anybody is doing today.

Al Letson: That’s next on Reveal.

From the Center for Investigative Reporting and PRX, this is Reveal. I’m Al Letson. While he was in Montana, Reveal’s Jonathan Jones talked to many policymakers who were quick to dismiss clean energy. For a lot of them, the commitment to coal and other fossil fuels comes down to jobs, tax revenue, or a disbelief in climate change. And there’s one more thing.

Gary Parry: The sun’s not always going to shine and the wind’s not always going to blow.

Al Letson: In other words, reliability.

Steve Gunderson: The biggest problem that we have in trying to do this changeover to wind, solar, those two especially, is they’re not an on demand. They are when the wind blows, when the sun shines.

Steve Fitzpatrick: The fact of the matter is in the middle of the dead of winter, when it’s super cold, there is no wind blowing.

Jason Small: When the wind’s not blowing, obviously you’re not getting wind power. There’s no solar energy today because it’s snowing.

Al Letson: That was state representatives Gary Parry and Steve Gunderson and Senators Steve Fitzpatrick and Jason Small. Montana’s largest utility company seems to agree. This spring, NorthWestern Energy unveiled its plans for supplying electricity across the state. That plan included burning more coal at the Colstrip power plant for the next two decades and finishing construction on their new gas plant on the Yellowstone River. Utilities across the west are phasing out their coal fire plants and pivoting to renewable energy. So why is one of Montana’s biggest energy players expanding its fossil fuel footprint? Jonathan went to ask the man behind the decisions at NorthWestern, the CEO.

Jonathan Jones: Brian Bird has worked for NorthWestern Energy for two decades. He became CEO at the beginning of 2023. Before that, he was president and chief operating officer. I asked him what he’s learned in his time at the head of the organization.

Brian Bird: We have a capacity problem at NorthWestern. And what I mean by capacity, we don’t have a sufficient amount of resources to deliver 24/7 power to our customers.

Jonathan Jones: Right now, NorthWestern imports energy from out of state to address that capacity issue. The company has to balance the electricity demands of its customers and the growing population in Montana. But it’s also a publicly traded company that has to make money for its shareholders, big investment firms like BlackRock and Vanguard, which manage the retirement funds of millions of Americans. Critics say that NorthWestern is sort of doubling down on outdated, inefficient, and polluting power sources because those are the most profitable and they’re making Montanans pay the bill. What’s your response to that?

Brian Bird: I’m doing that because our customers need that capacity. If I can’t deliver it to them, they’re going to be very angry with us as a utility, so it has nothing to do with profitability.

Jonathan Jones: About 58% of the electricity NorthWestern supplies in Montana generates zero carbon emissions. Some of it comes from wind power, some from hydroelectric dams, a along with a little bit of solar. He says the company is committed to adding more renewable resources.

Brian Bird: So it’s a false narrative to say that we’re not doing anything from a renewable energy perspective.

Jonathan Jones: But you are building the new gas plant.

Brian Bird: I am indeed, and that gas plant was built to offset the intermittency of renewables put on the system. I need to balance reliability, affordability, and sustainability, and I’m doing as quickly as I can to not only serve our customers today, but to serve them with cleaner energy in the future.

Jonathan Jones: Why do you think NorthWestern has been such a target of criticism among environmentalists in Montana?

Brian Bird: That’s a great question. I think the fact that we continue to be in a coal fire plant is probably the primary reason.

Jonathan Jones: Do you worry about climate change?