To fight teacher shortages, schools turn to custodians, bus drivers and aides

MORGAN CITY, La. — Jenna Gros jangles as she walks the halls of Wyandotte Elementary School in St Mary’s Parish, Louisiana. The dozens of keys she carries while she sweeps, sprays, shelves and sorts make a loud sound, and when children hear her coming, they call out, “Miss Jenna!”

Gros is head custodian at Wyandotte, in this small town in southern Louisiana. She’s also a teacher-in-training.

In August 2020, she signed up for a new program designed to provide people working in school settings the chance to turn their job into an undergraduate degree in education, at a low cost. There’s untapped potential among people who work in schools right now, as classroom aides, lunchroom workers, afterschool staff and more, the thinking goes, and helping them become teachers could ease the shortage that’s dire in some districts around the country, particularly in rural areas like this one.

In two and a half years, the teacher training program, run by nonprofit Reach University, has grown from 50 applicants to about 1,000, with most coming from rural areas of Louisiana, Arkansas, Alabama and California. The “apprenticeship degree” model costs students $75 dollars a month. The rest of the funding comes from Pell Grants and philanthropic donations. The classes, which are online, are taught by award-winning teachers, and districts must agree to have students work in the classroom for 15 hours a week as part of their training.

“We have overlooked a talent pool to our detriment,” said Joe Ross, president of Reach University. “These people have heart and they have the grit and they have the intelligence. There’s a piece of paper standing in the way.”

Efforts to recruit teacher candidates from the local community date back to the 1990s, but programs have “exploded” in number over the past five years, said Danielle Edwards, assistant professor of educational leadership, policy and workforce development at Old Dominion University in Virginia. Some of these “grow your own” programs, like Reach’s, recruit school employees who don’t have college degrees or degrees in education, while others focus on retired professionals, military veterans, college students, and even K12 students, with some starting as young as middle school.

“‘Grow your own’ has really caught on fire,” said Edwards, in part because of research showing that about 85 percent of teachers teach within 40 miles of where they grew up. But while these programs are increasingly popular, she says it isn’t clear what the teacher outcomes are in terms of effectiveness or retention.

Related: Teacher shortages are real, but not for the reasons you’ve heard

Nationwide, there are at least 36,500 teacher vacancies, along with approximately 163,000 positions held by underqualified teachers, according to estimates by Tuan Nguyen, anassociate professor of education at Kansas State University. At Wyandotte, Principal Celeste Pipes has three uncertified teachers out of 26.

“We are pulling people literally off the streets to fill spots in a classroom,” she said. Surrounding parishes in this part of Louisiana, 85 miles west of New Orleans, pay more than the starting salary of $46,000 she can offer; some even cover the full cost of health insurance.

Data suggests not having qualified teachers can worsen student achievement and increase costs for districts. An unstable workforce also affects the school culture, said Pipes: “Once we have people here that are years and years and years in, we know how things are run.”

As Gros walks the hallways, she stops to swat a fly for a scared child, ties a first grader’s shoelaces and asks a third about their math homework. Her colleagues had long noticed her calm, encouraging manner, and so, when a teacher’s aide at Wyandotte heard about Reach, she urged Gros to sign up with her.

Gros grew up in this town — her father worked as a mechanic in the oil rigs — and always wanted to be a teacher. But with three children and a salary of $22,000 a year, she couldn’t afford to do so. The low cost and logistics of Reach’s program suddenly made it possible: Her district agreed to her spending 15 hours of her work week in the classroom, mentoring or tutoring students. She takes her online classes at night or on weekends.

Current employees are also in the retirement system, meaning the years they’ve already worked count toward their pension. For Gros, who has worked for 18 years in her school system, that was an important consideration, she said.

Pipes said people like Gros understand the vibe of this rural community — the importance of family, the focus on church, the love of hunting. And people with community roots are also less likely to leave, said Chandler Smith, the superintendent in West Baton Rouge Parish School System, a few hours’ drive away.

His district is the second-highest paying in the state but still struggles to attract and retain teachers: It saw a 15 percent teacher turnover rate last year. Now, it has 29 teacher candidates through Reach.

Related: Uncertified teachers filling holes across the South

In West Baton Rouge Parish, Jackie Noble is walking back into the Brusly Elementary school building at 6:45 p.m. She’d finished her workday as a special education teacher’s aide around 3:30 p.m., then babysat her granddaughter for a few hours, spent time with her husband, and picked up a McDonald’s order of chicken nuggets, a large coffee and a Coke to get her through her evening classes. Some Reach classes go until 11 p.m.

Noble was a bus driver in this area for five years, but she longed to be a teacher. When she mustered the courage to research options for joining the profession, she learned it would cost somewhere between $5,000 to $15,000 a year over at least four years. “I wasn’t even financially able to pay for my transcript because it was going to cost me almost $100,” she said.

When Noble heard about Reach and the monthly tuition of $75 a month, she said, “My mouth hit the floor.”

Ross, of Reach University, said he often hears some variation of: “I had to choose between a job and a degree.”

“What if we eliminate the question?” he said. “Let’s turn jobs into degrees.”

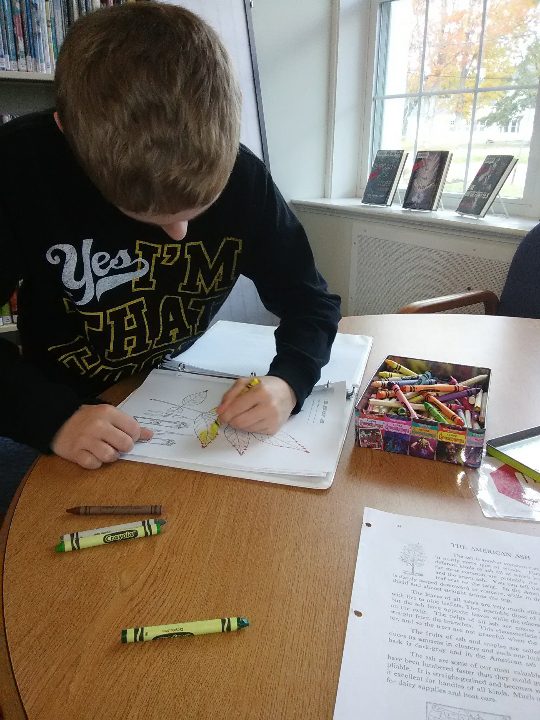

Brusly Elementary is quiet as Noble settles down in a classroom. She moves her food strategically off camera and ensures she has multiple devices logged in: her phone, laptop and desktop. Sometimes the internet here is spotty, and she doesn’t want to take any chances.

It’s the night of the final class of her course, “Children with Special Needs: History and Practice.” Her 24 classmates smile and wave as they log on from different states. They’ve been taking turns presenting on disabilities such as dyslexia, brain injuries and deafness; Noble gave hers, on assistive technologies for children with physical disabilities, last week.

Reach began in 2006 as a certification program for entry-level teachers who had a degree but still needed a credential. It then expanded to offer credentials to teachers who wanted to move into administration as well as graduate degrees in teaching and leadership. In 2020, Reach University started the program focused on school employees without a degree.

Kim Eckert, a former Louisiana teacher of the year and Reach’s dean, says she was drawn to the program because, as a high school special education teacher, she saw how little opportunity there was for classroom aides in her school to boost their skills. She started monthly workshops specifically for them.

In growing the Reach program, Eckert drew from her teacher-of-the-year class, hiring people who understood the realities of classroom management and could model what it’s like to be a great teacher. She shied away from those who haven’t proven themselves in the classroom, even if they have degrees from top universities. “Everybody thinks they can be a teacher because they’ve had a teacher,” she said, but that’s not true.

The 15 hours a week of “in-class training,” which can include observing a teacher, tutoring students or helping write lessons, is designed to allow students to test out what they’re learning almost immediately, without having to wait months or years to put their studies into practice. Michelle Cottrell Williams, a Reach administrator and Virginia’s 2018 teacher of the year, recalls discussing an exercise in class about Disney’s portrayal of historical events versus the reality. One of her students, a classroom aide, shared it with the fifth graders she was working with the next day.

Noble says she’ll carry lessons about managing students from the bus to her classroom. She was responsible for up to 70 students while driving 45 miles an hour — so 20 in a classroom seems doable, she said.

She can’t wait to have her own classroom where she is responsible for everything. “Being with the students approximately eight hours a day, you make a very, very larger impression on their lives,” she said.

Related: In one giant classroom, four teachers manage 135 kids — and love it

In May, Reach graduated its first class of teachers, a group of 13 students from Louisiana who had prior credits. The organization’s first full cohort will walk across the stage in spring 2024.

There are promising signs. Nationwide, about half of teacher candidates pass their state’s teaching licensure exam; more than 60 percent of the 13 Reach graduates did. All of them had a job waiting for them, not only in their local community, but in the building where they’d been working.

But Roddy Theobald, deputy director of the National Center for Analysis of Longitudinal Data in Education Research and researcher at the American Institutes for Research, says far more research is needed on “grow your own” programs. “There’s very, very little empirical evidence about the effectiveness of these pathways,” he said.

One of the challenges is that the programs rarely target the specific needs of schools, he said. Some states have staffing shortages only in specific areas, like special education, STEM or elementary ed. “Sometimes they result in even more teachers with the right credentials to teach courses that the state doesn’t actually need,” he said.

Edwards, one of the first researchers to study “grow your own” programs, is investigating whether teachers who complete them are effective in the classroom and stay employed in the field long term, as well as how diverse these educators are and whether they actually end up in hard-to-staff schools.

“States are investing millions of dollars into this strategy, and we don’t know anything about its effectiveness,” she said. “We could be putting all this money into something that may or may not work.”

Ross, of Reach University, says his group plans to research whether its new teachers are effective and stay in their jobs. In terms of meeting schools’ specific labor needs, Reach has agreements with other organizations such as TNTP (formerly The New Teacher Project) and the University of West Alabama to help people take higher-level courses in hard-to-fill specialties such as high school math. But while Reach staff look at information on teacher vacancies before partnering with a school district, they don’t focus on matching the district’s exact staffing needs said Ross: “Our hope is the numbers work themselves out.”

In Louisiana, Ross said he believes the organization could put a serious dent in the teacher vacancy numbers statewide. Some 84 percent of all parishes have signed on for Reach trainees, he said, and 650 teachers-in-training are enrolled. That amounts to more than a quarter of the teacher vacancy numbers statewide, 2,500.

“We’re getting pretty close to being a material contribution to the solution in that state,” he said.

His group is also looking to partner with states, including Louisiana, to use Department of Labor money for teacher apprenticeships. At least 16 states have such programs. Under a Labor Department rule last year, teacher apprenticeships can now access millions in federal job-training funds. Reach is in talks to use some of that money, which Ross says would allow it to make the programs free to students and rely less on philanthropy.

A straight-A student since her first semester, head custodian Jenna Gros expects to graduate without any debt in May 2024. She expects to teach at this same elementary school. At that point, her salary will almost double.

She said she loves how a teacher can shape a child’s future for the better. “That’s what a teacher is — a nurturer trying to provide them with the resources that they are going to need for later on in life.

I think I can be that person,” she said. She pauses. “I know I can.”

This story about grow your own programs was produced by The Hechinger Report, a nonprofit, independent news organization focused on inequality and innovation in education. Sign up for the Hechinger newsletter.

The post To fight teacher shortages, schools turn to custodians, bus drivers and aides appeared first on The Hechinger Report.