What Does it Mean to be wild?

Essay

What Does it Mean to Be Wild?:

A trip to a bear den with wildlife biologists yields more questions than answers

One curious member of the public, who joined state wildlife biologists on an excursion to a bear den, poses for a photo with the tranquilized black bear. Photo credit: Emily Arntsen

by Emily Arntsen – 8.17.2023 – 20 min. read

In the doldrums of late summer, when the Book Cliffs are thirsty and barren, black bears clamber down to Green River, Utah, to feast on the town’s famous fruits. The locals call them Melon Bears.

Some say the Melon Bears are bad omens. To see one means the drought is dire, means the sheep are in danger, means fewer crops for sale.

“When we get bears down in the valley, it’s usually an old bear that’s having trouble, or a sow with cubs that can’t find food,” said Darrel Mecham, a Green River resident and lifelong bear hunter. “Means it was a dry year.”

Meat makes up less than 10 percent of a black bear’s diet, but if forage is scarce, they will eat other animals. To protect their livestock, ranchers in Green River will sometimes call the Utah Division of Wildlife Resources (DWR) to remove black bears from town.

Mecham, a former Grand County chief deputy sheriff, said he has helped the state’s DWR catch these bears and haul them off to more suitable habitats on multiple occasions. But they never stay away for too long, he said.

“I remember they transported one boar to Fish Lake, and he was seen about a week later on I-70 coming back to Green River,” he said. Fish Lake is over 100 miles away. “We can’t keep them out of here.”

Melon farming factors heavily in the story Green River residents tell about themselves, as demonstrated by the annual Melon Days parade and fair. And though the Melon Bears are a nuisance to some farmers, they are also celebrated for their role in the town’s mythology. The image of a black bear in a melon patch, of an apex predator that prefers soft fruits, is not only endearing and perfectly storylike, but a testament to the sweetness of Green River’s prized crops.

In the town’s John Wesley Powell River History Museum, there is one Melon Bear to commemorate all Melon Bears. He is stuffed and eternally posed with a slice of foam watermelon in his claws, an offering to his afterlife.

This Melon Bear is Mecham’s. “He wasn’t actually in a melon patch when I got him. I got him up in the [Book Cliffs] mountains,” he said. “But we put him there to tell the story of the Melon Bears.”

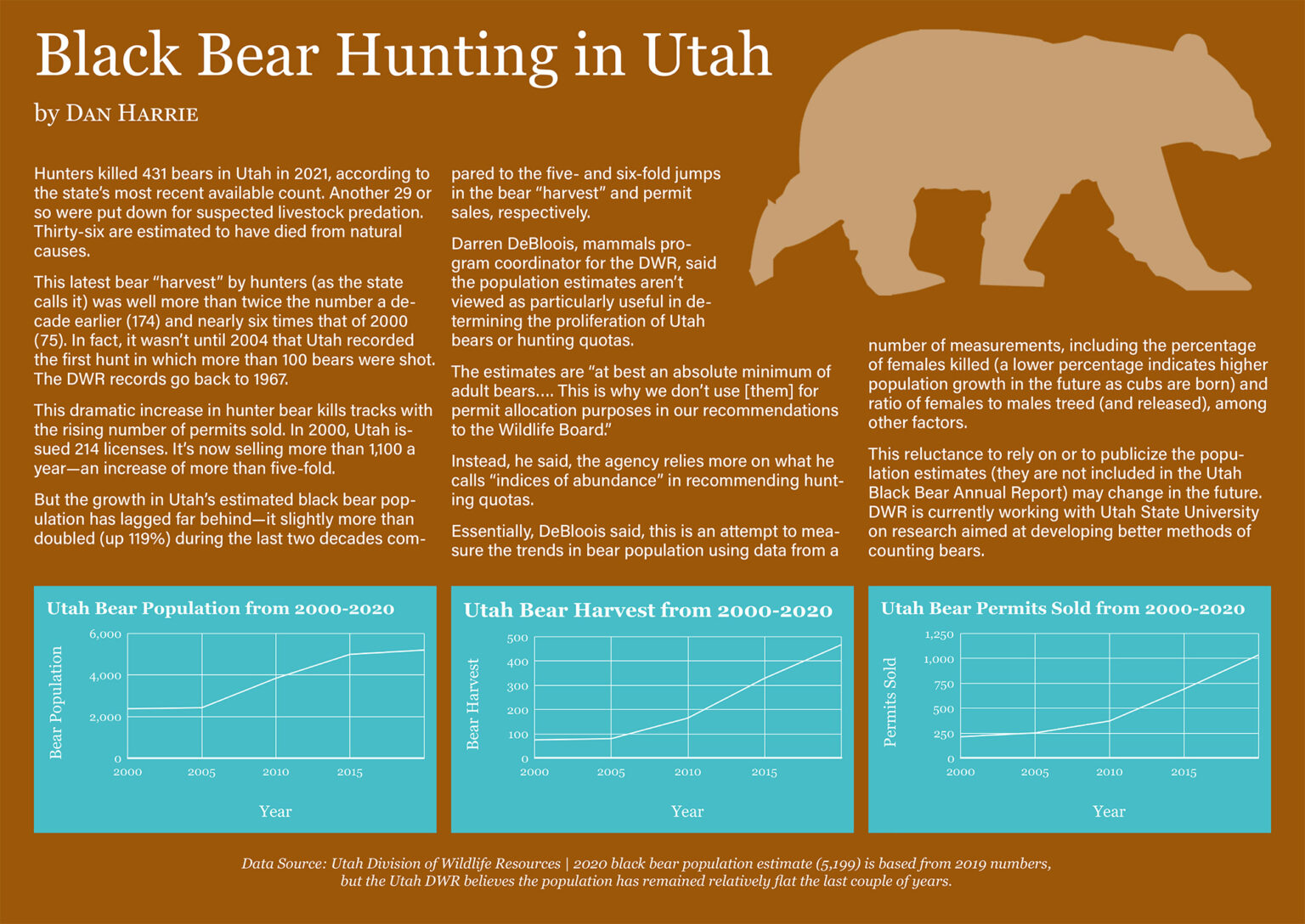

Every spring, DWR biologists visit about 30 bear dens across Utah, the locations of which they find using coordinates from GPS collars worn by hibernating sows. The main objective of these visits is to tally the number of cubs born to those sows, a number biologists use to help estimate the black bear population across the state. Right now, the population is somewhere around 5,200, not counting yearlings and cubs.

The goal of Utah’s black bear program is to “manage the Utah black bear populations consistent with habitat, biological and social constraints, and to meet the needs of the resource and the resource user.”

In this context, the “resource” is black bears, and the “resource user” is the people who hunt them.

“We want to make sure the population is healthy,” said DWR wildlife biologist Brad Crompton. “We need to know how many bears we have so we can estimate the harvest objective.” The “harvest” is how many black bears are killed each season. For Utah residents, a black bear hunting permit with the intention to harvest costs $83. The same permit costs $354 for non-residents.

For months, I had been emailing DWR biologists for an invite to a bear den. It was a snowy winter, though, and I was discouraged by the offers I had received so far—a 34-mile round-trip snowmobile ride, for example, and I would need to bring my own snowmobile. Finally, Crompton and another DWR wildlife biologist, Joe Christensen, had an “easy one” for me.

I met the biologists, plus the unexpected group of curious individuals joining us, on the side of Interstate 70 at the turnoff for one of Utah’s famed ghost towns, population 4. I include this detail only to highlight the size of our group, which was more than triple the population of this town. I remember thinking that 13 seemed like excessive company for an ice climb to a bear den, but what did I know?

“People love to see the cubs,” said Crompton, who’d let his teenage daughter skip school for the occasion. “We always invite the public.”

As such, it was an eclectic group with varying motives and degrees of preparedness. Crompton brought his daughter. Christensen brought his son. There were three college boys from Price, plus a bear biologist from Salt Lake City, who endured over an hour of hiking in knee-deep snow in high-heeled ankle booties, a baffling choice given her prior experience with field research in this exact niche. She was accompanied by her husband, a rock climber, who actually turned out to be useful given the extremity of the hike. There was also a young couple from Cleveland, Utah who brought their 4-month-old son in a baby backpack. The father introduced himself as Hans, “like hands,”and then he waved at me, in case it still was unclear.

Related Articles:

Hypervisitation, the Fate of the National Parks, and Tourism Toxification in a Small Town

April 12, 2023

9 Comments

Wildlife biologists Brad Crompton and Joe Christensen (foreground) prepare the tranquilizer gun before entering a black bear den in the Book Cliffs mountains in Utah

Photo credit: Emily Arntsen

Before we embarked on the hike, we had a team meeting of sorts during which Crompton told us the history of this bear.

“She was an abandoned cub,” he explained. “Her mother ate some sheep and had to be killed by government trappers. So we took her in as a cub and eventually released her to the wild, and we’ve been tracking her ever since. That was thirteen years ago.”

I asked if tracking a bear since birth disqualified her from being “wild.” “I don’t know,” he said. “I’ve never thought about that.”

Before we began the hike, I took inventory of my comrades. I was bewildered by some of the fashion choices. No one looked particularly ready for an ice climb. And although I’m not sure what one would wear to prepare for a bear encounter, no one looked ready for that either.

“Like Hands” especially stood out to me. In addition to the baby strapped to his back, he wore a red-and-white gingham shirt under a canvas vest. On one hip, he had a pistol in a carved leather holster that he kept flush to his bootcut jeans with a delicate piece of cord that looped around his thigh like a garter. On the other hip, he wore his cellphone. His eyes were shielded from the sun by a straw hat and wraparound orange sunglasses.

Frankly, he looked great. Describing his outfit warrants no further explanation, in my opinion. But as it pertains to this story, I include these details mostly to highlight the absurdity of the situation. The specificity of his cowboy apparel only enhanced the uncanny feeling that we were play-acting what felt like an AI-generated thriller if the algorithm had been fed “The Revenant” and “Donner Party” and “Utah stereotypes.” In other words, I had a weird feeling about this, even before we started hiking.

We started off toward the GPS coordinates and quickly found ourselves doubling back in search of a less direct but less arduous route. “Finding her is the hardest part,” Christensen said. I found this hard to believe, since I knew he and Crompton would eventually have to crawl into a wild animal’s den.

“This is why I love bear denning. It gets you out to places you’d never go otherwise,” Crompton remarked at one point. True, I thought, as many of us slid backwards down the ravine.

Eventually, Crompton and Christensen ventured off to scout the best route. The rest of us waited on a narrow ledge. We were cold in the shade, and the baby was crying. When Crompton returned, he warned that the route would get “a little cowboy.” We kicked our toes into the hard snow for traction and pitched forward with the grade of the ravine toward another narrow ledge. “I should have brought a rope, I guess,” Crompton said.

Wildlife biologist Brad Crompton peeks into the black bear den before crawling in to tranquilize the animal.

Photo credit: Emily Arntsen

At one point, someone dislodged a rather large rock, which slid noisily down the ice. We all called out “rock!” in descending order, then looked down, helplessly.

Before arriving at the entrance of the den, Christensen asked us to be quiet so as not to wake the bear. This request went largely ignored. A college boy with a fear of heights announced that he would be turning back now, and the baby was wailing.

“Do you think she’s heard us?” I whispered to Christensen. “I hope not,” he whispered back. Then he broke a branch off a nearby juniper. “I forgot my shovel,” he said. With comic inefficiency, he dug out the entrance of the den.

At some point it occurred to me that I was directly in front of and eye-level with the opening of the den. I imagined the bear emerging angrily and roaring in my face. Though I knew this would most likely not happen, neither the journey here nor this cast of characters had inspired much confidence in what we were doing. I looked down at my boots, the exact width of the ledge, and then at the cascade of ice behind me, and decided to relocate to a rock above the den.

From this vantage point, I could see Christensen and Crompton, who had walked out of sight of the rest of the group to load the tranquilizer gun with a mixture of Ketamine and Xylazine. I suppose they thought we didn’t want to see this. We came to see cubs, not a bear in a k-hole, though that was a necessary part of this operation.

The two biologists awkwardly navigated the narrow ledge through the group toward the den as everyone closed in around them, vying for a good view. The two remaining college boys took out their phones and started recording, overshooting the action by at least 10 minutes.

Crompton paused in front of the hole, which was only a little wider than his shoulders, then adjusted his headlamp and crouched down. He climbed face-first into the den until his boots disappeared. I stuck my recorder as far into the hole as I dared and heard his one-way conversation with the bear.

“Hey bear,” he said with the kind of pleading cadence one might use with an angry dog. “Nice bear,” he cooed. Then his tone changed abruptly. “Oh, that’s your face,” he said. “Oh, you’re awake.” Then I remembered what he said earlier when I asked if the tranquilizer ever failed. “Yeah, often actually,” he had said.

Crompton said, “Gun!” and reached back to the entrance of the den, where Christensen was holding his ankles. Christensen loaded the gun into his hand. “Cocked, right?” Crompton asked. Christensen paused. “I think so,” he said.

A dull crack came from inside the den, and then Christensen pulled Crompton out of the hole by his legs. “Got her,” Crompton said, out of breath. In the movie version of this scene, there would have been music. Instead, it was unusually quiet, as it always is in real life during what you think is the climax.

“Now we wait,” Christensen said. We all stood quietly facing the den. We had to wait about 10 minutes for the tranquilizer to kick in. I got the sense that some people were bored.

Crompton eventually crawled back into the den and asked the bear if she was “good and asleep.” No answer, and so he pulled her out by her front legs, and then by her head. “No cubs,” he confirmed.

I had never seen a black bear this close before, but even I could tell that she was unusually skinny. Her shoulder blades stood up like dorsal fins. The fur around her temples was thin, and I could see through to her pale skin. “You’re kind of scruffy, aren’t you?” Crompton said to the bear.

I don’t know why I was shocked that her eyes were open, but I found this deeply unsettling. Could she see? The more accurate term for this kind of tranquilization is “dissociation.” This means that “physically, their eyes still function, but it doesn’t register in their brain or memory,” said another DWR wildlife biologist, Vance Mumford, to me during a different interview about tranquilization of wild animals. “Of course we don’t know exactly what they can see or remember, but judging by their reactions, I think it’s very little,” he said, relating it to his own experiences of not remembering under general anesthesia.

“She won’t remember a thing,” Crompton had said to me on the way up. But as someone who used to blackout with a frequency I’m not proud of, I know that this limbo state of consciousness is not so much a matter of pausing the recorder as it is an obscuring of files. The body holds every memory. Some are just hard to find. I looked into her unfocused eyes, small and brown and almond-shaped like a human’s, and I wondered where she would store this image of my face and whether it would ever resurface in her memory.

The glory of the Melon Bear was lost on this crowd. The fancy footwear biologist honored no ceremony when she snipped and pocketed a lock of fur. “You don’t mind, do you?” she asked Crompton, as if the fur belonged to him. He shrugged.

One of the college boys pulled back the bear’s lips to examine her teeth, which were yellow and larger than I expected. He grabbed a fistful of fur from the scruff of her neck and held her head up for a photo. Her jaw was slack from the muscle relaxant, and her tongue was lolling slightly out of her mouth in a way that made me want to tell everyone to shut up and stop touching her.

I asked Crompton why he thought she didn’t have cubs. “Last summer was mighty dry,” he said. “Not a lot of forage.” In order to survive the winter with a newborn, a sow has to eat for at least two in the months leading up to hibernation. After mating, the embryo waits in the uterus for the change of seasons. By the start of fall, if the sow has stored enough fat, the embryo will take, and she’ll give birth in the den that winter. “She most likely mated this summer,” Crompton guessed, based on the every-other-year mating cycle of a sow her age.

The young couple put their baby on the bear’s back, as if to ride her. This was equal parts touching and disturbing. Mama Bears and babies go together. But this bear was too thin to be a mama this year. And this bear did not look like a teddy bear. She looked dead.

A taxidermied black bear holds a piece of foam watermelon in John Wesley Powell River History Museum in Green River, Utah, to commemorate the Melon Bears that like to steal snacks from the town’s melon patches. Photo credit: Elayne Hinsch, collections manager at the John Wesley Powell River History Museum

The baby’s father held up the bear’s paw to me. Instinctively I raised my palm to hers and felt her calloused pads and the underside of her claws. It felt wrong to touch her. Her limb was twisted in an unnatural way to reveal her paw. I wanted him to put it down, but not as badly as I wanted to touch her claws. I was not above anyone else in this regard. I was excited by this perversion of the natural order and the chance to touch an animal I had no business touching. I posed for a photo with her, and in this photo, my smile is more like a grimace.

When we got down from the den, I felt a strange camaraderie with this group of people. Mere hours ago, we were 13 strangers, and then we all touched the same bear, and wasn’t that kind of f___ed up? Wasn’t that kind of special? Adrenaline was high. Blood sugar was low. I don’t remember anything from the drive home. That night I dreamt that I miscarried, and I woke up with a bad feeling about whatever curse I had set in motion the day before when I touched the Melon Bear.

Weeks later, I visited Darrel Mecham in Green River. He told me the story of his Melon Bear, and then the story of his other bear, his Final Bear.

Mecham, who is 61, has been hunting since he was a teenager. In all those decades, he’s killed only two black bears, but not for a lack of opportunity. “It’s not called killing,” he said. “It’s called hunting for a reason.”

For him, hunting is about the thrill of the chase and being in nature. “When you strap a pack on some pack mules and you ride alone on that old trail along the rim and you’re going up some remote canyon and all of a sudden you get a feeling and you look over and there’s a bear standing there watching you, that’s the real experience,” he said.

At some point in the conversation, I caught a glimpse of a stuffed bear in the next room.

“He’s a special bear. I’ll never take another,” Mecham said, gesturing to his Final Bear, raised up on his hind legs forever.

When Mecham was diagnosed with Ankylosing spondylitis in 2009, the doctor said he would most likely be paralyzed the rest of his life. “I met this bear right after I was told I was going to be crippled,” he said.

It was the end of what he thought might be one of his last hunts, and he was going home from the Book Cliffs empty-handed. “I hadn’t seen anything all day, but I was OK with that because at least I was able to ride out, and I wasn’t crippled,” he said. “But then we ran into each other, me and this bear. He looked at me, and I looked at him, and there was kind of a respect in that.”

Later I thought about my bear and how I had looked into her blank eyes. She had looked into mine, too, maybe. But I hadn’t rode my pack mule alone down that old trail along the rim to find her, hadn’t spent a lifetime crisscrossing the Book Cliffs where she dwelt, didn’t know the feeling of a bear watching me from afar, hadn’t earned it. And so, Melon Bear, I want to say I’m sorry. I’m sorry that this is how you greet the spring each year. I’m sorry you didn’t have any cubs. I’m sorry I came to your den and touched the underside of your limp paw, because there was no respect in that.

Republish

Republish Our Content

Corner Post’s work is available under a Creative Commons License and under our guidelines:

- You are free to republish the text of this article both online and in print (Please note that images are not included in this blanket licence as in most cases we are not the copyright owner) but:

- you can’t edit our material, except to reflect relative changes in time, location and editorial style and ensure that you attribute the author, their institute, and mention that the article was originally published on Corner Post;

- if you’re republishing online, you have to link to us and include all of the links in the story;

- you can’t sell our material separately;

- it’s fine to put our stories on pages with ads, but not ads specifically sold against our stories;

- you can’t republish our material wholesale or automatically—you need to select stories to be republished individually;

- you have to credit us, ideally in the byline; we prefer “Author Name, Corner Post,” with a link to our homepage or the article; and

- you have to tag our work with an editor’s note, as in “This article was paid for, developed, and originally published by Corner Post. Corner Post is an independent, nonprofit news organization. See cornerpost.org for more.” Please, include a link to our site and our logo. Download our logo here.

Emily Arntsen moved to Moab, Utah, in 2020. She works as a reporter at Moab’s KZMU Radio and has written for other publications about the people, the history, and the ecology of the Colorado Plateau. Before moving west, Emily worked in Boston, Massachusetts, as a science writer and radio producer.

Emily Arntsen moved to Moab, Utah, in 2020. She works as a reporter at Moab’s KZMU Radio and has written for other publications about the people, the history, and the ecology of the Colorado Plateau. Before moving west, Emily worked in Boston, Massachusetts, as a science writer and radio producer.

The post What Does it Mean to be wild? A trip to a bear den with wildlife biologists yields more questions than answers appeared first on Corner Post.