This transcript has been edited for length and clarity.

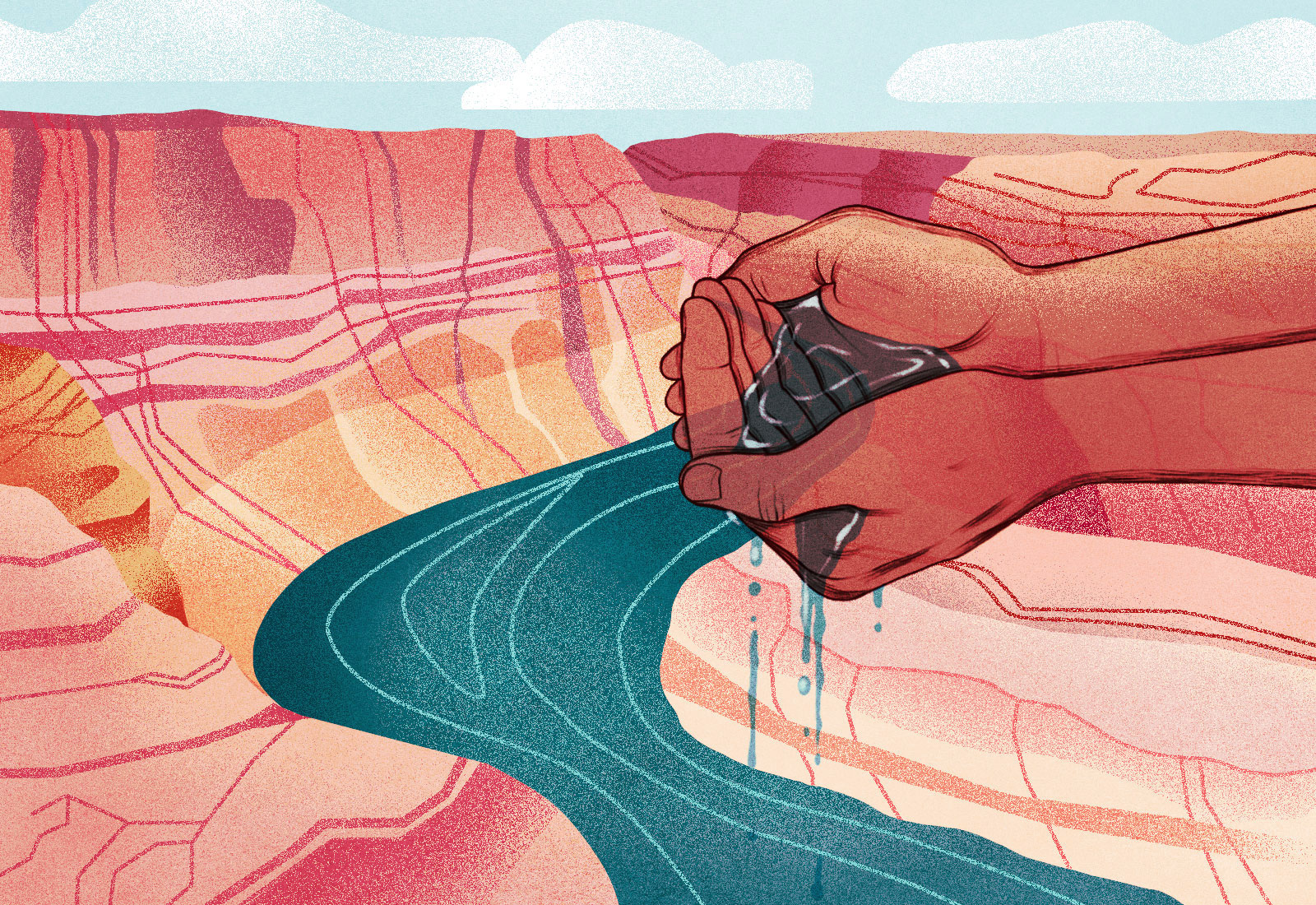

California and Arizona are currently fighting each other over water from the Colorado River. But this isn’t new — it’s actually been going on for over 100 years. At one point, the states literally went to war about it. The problem comes down to some really bad math from 1922.

To some extent, the crisis can be blamed on climate change. The West is in the middle of a once-in-a-millennium drought. As temperatures rise, the snow pack that feeds the river has gotten much thinner, and the river’s main reservoirs have all but dried up.

But that’s only part of the story: The United States has also been overusing the Colorado for more than a century thanks to a byzantine set of flawed laws and lawsuits known as the “Law of the River.” This legal tangle not only has been over-allocating the river, it also has been driving conflict in the region, especially between the two biggest users, California and Arizona, which are both trying to secure as much water as they can. And now, as a massive drought grips the region, the law of the river has reached a breaking point.

The Colorado River begins in the Rocky Mountains and winds its way southwest, twisting through the Grand Canyon and entering the Pacific at Baja California. In the late 19th century, as white settlers arrived in the West, they started diverting water from the mighty river to irrigate their crops, funneling it through dirt canals. For a little while, this worked really well. The canals made an industrial farming mecca out of desert that early colonial settlers viewed as “worthless.”

Even back then, the biggest water users were Arizona and California, which took so much water that they started to drain the river farther upstream, literally drying it out. According to American legal precedent, whoever uses a body of water first usually has the strongest rights to it. But other states soon cried foul: California was growing much faster than they were, and they believed it wasn’t fair that the Golden State should suck up all the water before they got a chance to develop.

In 1922, the states came to a solution — kind of. At the suggestion of a newly appointed cabinet secretary named Herbert Hoover, the states agreed to split the river into two sections, drawing an arbitrary line halfway along its length at a spot called Lee Ferry. The states on the “upper” part of the river — Colorado, Utah, Wyoming, and New Mexico — agreed to send the states on the “lower” end of the river — Arizona, California, and Nevada — what they thought was half the river’s overall flow, 7.5 million acre-feet of water each year. (An acre-foot is enough to cover an acre of land in a foot of water, about enough to supply two homes for a year.)

This agreement was supposed to prevent any one state from drying up the river before the other states could use it. The Upper Basin states got half and the Lower Basin states got half. Simple.

But there were some serious flaws to this plan.

First, the Law of the River overestimated how much water flowed through the river in the first place. The states’ numbers were based on primitive data from stream gauges placed at arbitrary points on the waterway, and they took samples during an unusually wet decade, leading to a very optimistic estimate of the river’s size. The river would only average about 14 million acre-feet annually, but the agreement handed out 15 million to the seven states.

While the states weren’t able to immediately use all this water, it set in motion the underlying problem today: The states have the legal right to use more water than actually exists in the river.

And you’ll notice that the Colorado River doesn’t end in the U.S. — It ends in Mexico. Initially, the Law of the River just straight-up ignored that fact. Decades later, Mexico was squeezed into the agreement and promised 1.5 million acre-feet, further straining the already over-allocated river.

On top of all of this, Indigenous tribes that had depended on the river for centuries were now forced to compete with states for their share of water, leading to these drawn-out lawsuits that took decades to resolve.

But in the short-term, Arizona and California struck it rich — they were promised the largest share of Colorado River water and should have been primed for growth. For Arizona, though, there was a catch: The state couldn’t put their water to use.

The state’s biggest population centers in Phoenix and Tucson were hundreds of miles away from the river itself, and it would take a 300-mile canal to bring the water across the desert — something the state couldn’t afford to build on its own. Larger and wealthier California was able to build all the canals and pumps it needed to divert river water to farms and cities. This allowed it to gulp up both its share and the extra Lower Basin water that Arizona couldn’t access. California’s powerful congressional delegation lobbied to stop Congress from approving Arizona’s canal project, as the state wanted to keep the Colorado River to itself.

Arizona was furious. And so, in 1934, Arizona and California went to war — literally. Arizona tried to block California from building new dams to take more water from the river, using “military” force when necessary.

Arizona sent troops from its National Guard to stop California from building the Parker Dam. It delayed construction, but not for very long because their boat got tangled up in some electrical wire and had to be rescued.

For the next 30 years, Arizona and California fought about whether Arizona should be able to build that canal. They also sued each other before the Supreme Court no fewer than 10 times, including one 1963 case that set the record for the longest oral arguments in the history of the modern court, taking 16 hours over four days and involving 106 witnesses.

That 1963 case also made some pretty big assumptions: Even though the states now knew that the initial estimates were too high, the court-appointed expert said he was “morally certain that neither in my lifetime, nor in your lifetime, nor the lifetime of your children and great-grandchildren will there be an inadequate supply of water” from the river for California’s cities.

A few years after that court case, in 1968, Arizona finally struck a fateful bargain to ensure it could claim its share of the river. California gave up its anti-canal campaign and the federal government agreed to pay for the construction of the 300-mile project that would bring Colorado River water across the desert to Phoenix. This move helped save Arizona’s cotton-farming industry and enabled Phoenix to eventually grow into the fifth-largest city in the country. It seemed like a success — Arizona was flourishing!

But in exchange for the canal, the state made a fateful concession: If the reservoirs at Lake Powell and Lake Mead were to run low, Arizona, and not California, would be the first state to make cuts. It was a decision the state’s leaders would come to regret.

In the early 2000s, as a massive drought gripped the Southwest, water levels in the river’s two key reservoirs dropped. Now that both Arizona and California were fully using their shares of the river, combined with the other states’ usage, there suddenly wasn’t enough melting snow to fill the reservoirs back up. A shrinking Colorado River couldn’t keep up with a century of rising demand.

Today, more than 20 years into the drought, Arizona has had to bear the biggest burden. Thanks to its earlier compromise decades earlier, the state had “junior water rights,” meaning it took the first cuts as part of the drought plan. In 2021, those cuts officially went into effect, drying out cotton and alfalfa fields across the central part of the state until much of the landscape turned brown. Still, those cuts haven’t been enough.

This century, the river is only averaging around 12.4 million acre-feet. The Upper Basin states technically have the rights to 7.5 million acre-feet, but they only use about half of that. In the Lower Basin, meanwhile, Arizona and California are gobbling up around three and four million acre-feet respectively. In total, this overdraft has caused reservoir levels to fall. It’s going to take a lot more than a few rainy seasons to fix this problem.

So, for the first time since the Law of the River was written, the federal government has had to step in, ordering the states to reduce total water usage on the river, this time by nearly a third. That’s a jaw-dropping demand!

These new cuts will extend to Arizona, California, and beyond, drying up thousands more acres of farmland, not to mention cities around Phoenix and Los Angeles that rely on the Colorado River. These new restrictions will also put increased pressure on the many tribes that have used the Colorado River for centuries: Tribes that have water rights will be pressured to sell or lease them to other water users, and tribes without recognized water rights will face increased opposition as they try to secure their share.

And Arizona and California are still fighting over who should bear the biggest burden of these new cuts. California has insisted that the Law of the River requires Arizona to shoulder the pain, and from a legal standpoint they may be right. But Arizona says further cuts would be disastrous for the state’s economy, and the other five river states are taking its side.

Either way, the painful cuts have to come from somewhere, because the Law of the River was built on math that doesn’t add up.

This story was originally published by Grist with the headline The very bad math behind the Colorado River crisis on Apr 26, 2023.