Hope in Turbulent Times: Native Leaders Take the Long View

In the wake of the 2024 election, Barn Raiser talks to prominent Native leaders and mentors, who tell us in edited interviews how and why their communities have long endured, even in divisive and unsettled times.

In the wake of the 2024 election, Barn Raiser talks to prominent Native leaders and mentors, who tell us in edited interviews how and why their communities have long endured, even in divisive and unsettled times.

Right now, all of us who live together on this earth face not just political instability but the “dual crises of climate change and social injustice,” according to Fawn Sharp, citizen of the Quinalt Indian Nation, in Taholah, Washington, and former president of the National Congress of American Indians.

“Now, more than ever,” Sharp says, “the world needs the wisdom, resilience and stewardship that Indigenous leaders uniquely bring. Our survival in this rapidly changing world may well depend on it.”

The views of each of those who spoke to Barn Raiser are deeply personal and rooted in their own unique cultures.

The Long View

For the past 16 years, the Zuni Youth Enrichment Project, at Zuni Pueblo in New Mexico, has hosted numerous programs in the arts, gardening, cooking, sports and more. The activities are designed to prepare Zuni youth to be healthy adults who can continue Zuni cultural traditions. Of Zuni’s 10,000 residents, almost a third are under the age of 18. Kiara Zunie, a Zuni tribal citizen and ZYEP’s Youth Development Coordinator, and ZYEP Operations Manager Josh Kudrna describe accompanying tribal youth on a recent visit to their people’s emergence place in what is now called the Grand Canyon. Zunie and Kudrna are joined in this interview by ZYEP Executive Director Tahlia Natachu-Eriacho, a tribal citizen.

Kiara Zunie: Backpacking down the Grand Canyon was a beautiful and humbling experience for everyone. We shared moments of aching legs, tingling fingers and shallow breathing from the weight of our packs. The journey reminded us that resilience isn’t just about physical strength, it’s about mental toughness, too. We took care of each another through consistent check-ins, positive encouragement and song lyrics. Each rugged step we took was also a reminder of our ancestors’ enduring strength and their prayers coming to fruition through a group like us.

Tahlia Natachu-Eriacho: This program is important for us because it acknowledges Zuni’s migration story. We Zuni people emerged from there and made our way to where we are now in Zuni Pueblo. The fact that we still live on the lands our ancestors intended us to be on is so powerful. And a privilege. Our reservation is where we are supposed to be.

We have been intentional about calling the trips to the Grand Canyon ‘visits.’ They’re not adventures or expeditions and other ideas that come from the goals of colonization. We are going to visit our relatives, to where our ancestors were, to places that have meaning for our culture and our identity and who we are today.

Josh Kudrna: During the three-day visit, we hiked 17 miles. That may not sound like a lot to people who run marathons, but it’s down about 7,000 feet to get to the water at the base of the canyon, then back up 7,000 feet. It’s very steep climbing, and all of our participants were carrying everything they needed—about 30 to 40 pounds—on their backs.

Ahead of time, I try to prep them for what’s about to happen, but it’s hard to conceptualize that after about three miles your legs will be quaking with every step. It’s very hard work, and they connect to the ancestors, who didn’t have fancy boots, who didn’t have internal-frame backpacks, but were still carrying their children and everything they needed on their backs as they continually went up and down the canyon.

Zunie: The day we hiked out of the Grand Canyon happened to fall on Indigenous People’s Day. We were nearing the top when we heard the echo of a drumbeat. The National Park Service had organized traditional dances to celebrate Indigenous culture. As we listened to the drums, I looked at the group, reminding myself of the journey we had just endured. Remembering the aches and pains and the moments of laughter and camaraderie, I started to cry.

A Place to Call Home

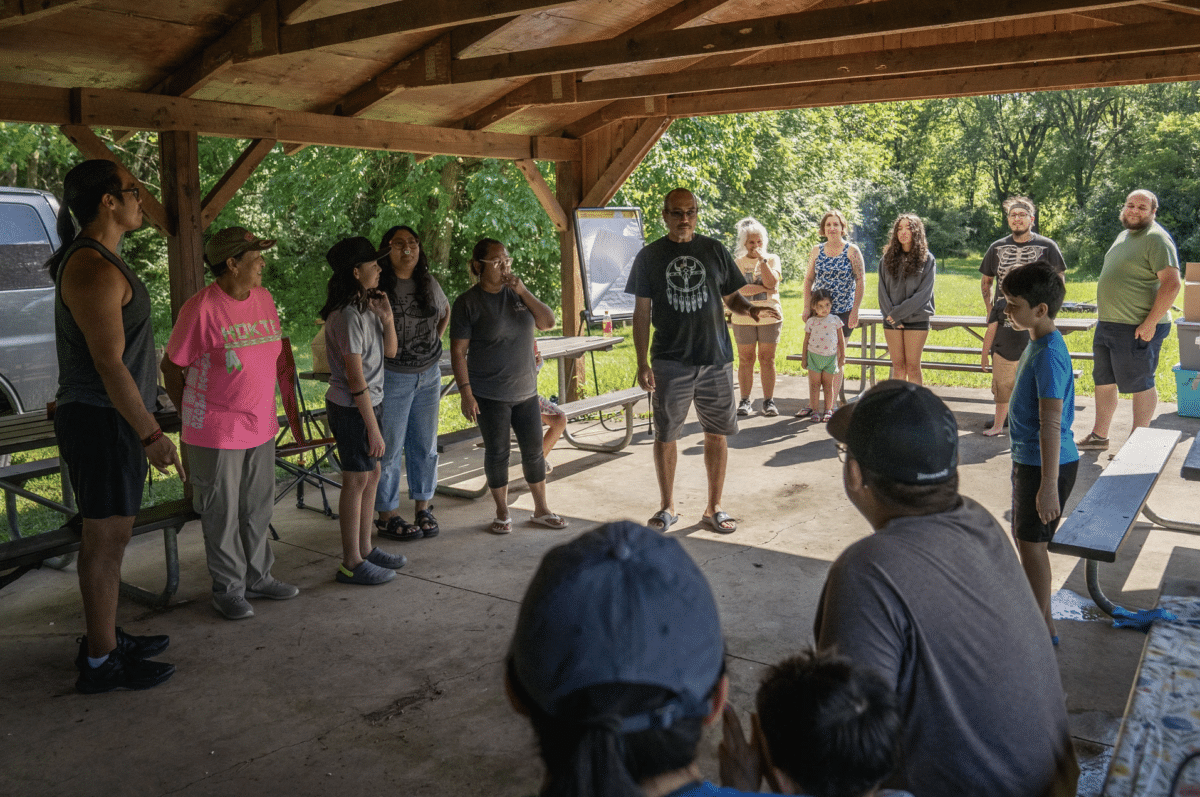

Good news is imminent at the Native American Community of Central Ohio (NAICCO), in Columbus. Executive Director Masami Smith and Project Director Ty Smith lead the urban-Indian organization and its activities on behalf of the cultural, community and economic development of the area’s Native people. Both Masami and Ty are enrolled citizens of the Confederated Tribes of Warm Springs, in Oregon. A major project nearing fruition is LandBack NAICCO, with nearly $400,000 in donations and earned income that will allow the group to acquire land. The group is currently looking at land in Central Ohio and the broader Ohio area. According to the major Indigenous news source Native News Online, many Native communities are finding ways to reconstitute portions of homelands and reservations lost in the process of European settlement. Ty tells us about NAICCO and its plans.

Ty Smith: The urban setting is different in many ways from Indigenous homelands on the reservations. You’re navigating two worlds simultaneously while trying to maintain balance and harmony in your life. The sense of home is strong for our Native people. But where do you find that in Ohio, which has no infrastructure for us—no tribes, which were expelled in the 1800s, no reservations, no Indian Health Service, no Bureau of Indian Affairs, no Bureau of Indian Education?

Because Ohio doesn’t include the tribes that were originally here, there are holes in the story. The dots don’t connect. Native people who have come to live here in recent years—for higher education, work and more—lean on each other. They come into NAICCO and start to make it home and make relations.

As an intertribal community, we bond in ways we never thought possible. A sense of togetherness and belonging has become the heart and soul of NAICCO. We all agree that we want a better tomorrow for our children. When you have that commonality, it speaks truth. It’s our foundation. The group becomes family, not by blood but by shared experience in the newfound Ohio home.

Since Masami and I came here in 2011, people have asked, “What if we could have our own place?’ While doing other programs, we never lost track of that: a piece of land in addition to our agency building on the south side of Columbus, a place we could call home, where we could connect with Nature.

We launched LandBack NAICCO in 2019, right before Covid struck. It didn’t get a lot of traction because of the pandemic. So we re-launched it in 2022. To our surprise, wow, in 2024 we have almost $400,000 to buy land that is not just ours, but where we can reawaken the Native within. Land that we don’t just walk upon, but where we engage in foraging, tending, stewarding, rewilding and conservation, where we can create a relationship with Mother Nature. How does Nature teach us, how do we take care of her? This is essential to who we are.

Native people have advocated for this idea, of course. It’s exciting, surprising and humbling that non-Native relatives, supporters, friends and allies have also rallied behind us and lifted us. Non-Native subject-matter experts, including conservationists and environmentalists, have told us that once we have the land, let them know. They’re there to offer resources, services, insight, wisdom. Very cool. Multiple organizations and private parties have come forward to participate as well. We don’t know how this will end. It’s hard to talk about because it’s happening right now, in real time.

We never imagined this in our wildest dreams. In these turbulent times, it gives you hope that there’s something good at hand. It points to a good life, not just for the individual but for the community. There’s hope here and a dream. LandBack NAICCO is about planting seeds for a better tomorrow.

Strengthening Connections

Anahkwet (Guy Reiter) is a citizen of the Menominee Indian Tribe of Wisconsin and executive director of the grassroots nonprofit Menikanaehkem Community Rebuilders. The group has a range of supportive programming, including building solar-powered “tiny homes” for those who need shelter during life transitions, setting up women’s leadership and empowerment projects, including midwifery and traditional birthing practices, developing forest- and garden-based food sovereignty and advocating against proposals for dangerous open-pit mines and pipelines. Anahkwet talks about how his tribe understands the connections that strengthen individuals and communities.

Anahkwet: With the results of the recent election, hopefully people will now understand what this country has always been about since 1492. This moment is like many other moments in our Indigenous history with the dominant society. We at Menominee have been here before, unfortunately sometimes in more dire circumstances.

If you haven’t figured it out yet, our greatest enemy is the European mind, which comes in many shapes, forms, colors and creeds. It’s such a dangerous outlook because it’s based in fear. Through its languages, it perceives problems, defines them and builds things around them in ways that isolate a person—on a planet with 8 billion people. Anything built on fear and distrust never ends well. It’s a shaky foundation to build anything on.

Our Menominee language isn’t like that. It’s built on relationships, love and a connection to all things. The more we move in that direction, the stronger we will get. Indigenous leadership in this regard is already there throughout the world. It’s a question of others waking up to it and realizing it. Indigenous leaders have been present this whole time, but others haven’t seen them, haven’t taken the time to listen to them.

Our people are amazing at—and have mastered—resilience. Their deep connections to our culture and our language have kept them deeply grounded and able to withstand much struggle and oppression. Without those connections, you can see that a person might feel hopeless, lost, confused.

For us, struggle strengthens our connections. It alerts us to the importance of remembering who we are—our languages, our culture, our ceremonies. It’s a reminder to continue them. Our young people can see the sacrifices of their ancestors. They see the reason we’re still here, through all the things that happened to us. They see that our language, our culture and our way of life have held us together—have given us all we need in terms of hope, understanding and direction.

One of our greatest teachers is the Earth. If you slow down and listen, she’ll show you exactly what you need to know. If you want to build an organization, look to a forest. How does a forest have that much diversity, yet life thrives? What characteristics of a healthy forest do you see? In our teachings, in our culture, we talk about representation from grandma and grandpa trees, adult trees, teen trees, baby trees. They all need to exist within that ecosystem for it to be healthy. It doesn’t take long to understand the simplicity of it all. If you’re able to slow down and connect with the Earth, the answers are there.

When we went ricing this year, we took our young people along. [While ricing, one person poles a canoe through the shallow water of a wild-rice paddy, while the other uses sticks to tap the ripe wild-rice grains into the canoe.] It’s more than getting in a canoe, getting in the water and paddling, which is amazing in itself. Understanding the relationship the canoe has to the water and we have to the canoe, the connection to the trees, the land, the fish—all those things come into play. Before we go ricing, we pray. We ask for good days. We make sure everyone is safe.

The canoe in the water can teach you a lot of things about yourself. It can show you how you relate to another person. If it’s a windy day, you understand quickly how much teamwork ricing takes. When the wind is blowing hard in your face, the two of you are not going to make it across the lake if you don’t take the time to understand each other’s strengths and weaknesses, to work together. You’re also not fearful. You don’t make quick reactions. In this world, everyone wants quick this, quick that, but it’s not like that in the natural world.

Our people have stressed we must have good thoughts as we harvest this rice that has nourished our people for thousands of years. We harvest with a good heart and a good mind. We do it to feed our families, as well as other families, so they won’t go hungry. We think of all those who came before us, who treated the rice as we do, so it would continue to thrive. It will continue to take care of us if we take care of it.

All people around the world have gone through times like these at various points in their histories. In those times, they found strategies, ways to move forward. Today, there are good people and amazing things happening. Someone once told me in reference to a hurricane in Florida that all over the news you see what a tragedy it is. News shows show the destruction and the horrors.

But, this person said, remember to look for the helpers—helping, doing their work. The same is true now. Look for the helpers. They’re doing their work.

The post Hope in Turbulent Times: Native Leaders Take the Long View appeared first on Barn Raiser.