Centering Indigenous Knowledge in Environmental Justice

Out-of-state landlords received millions from Oregon’s COVID landlord fund

Underscore News

Underscore produces collaborative journalism framed by justice to promote civic engagement and a fair-minded society.

Columbia Insight

Columbia Insight’s mission is to inform and inspire readers with original, balanced journalism about environmental issues affecting the Columbia River Basin.

Highway 58 Herald

Highway 58 Herald provides news and information for all communities along the 87-mile scenic corridor through the Oregon Cascades.

Green Colonialism is Flooding the Pacific Northwest

Three Decades of Well Water Pollution in Rural Oregon Sees Almost No Government Action

Community organizers band together to tackle pollution from food processors and industrial farming. By Claire…

The post Three Decades of Well Water Pollution in Rural Oregon Sees Almost No Government Action appeared first on InvestigateWest.

EXCLUSIVE: Businessman proposing data center on banks of Columbia River has history of troubled deals

City mayor says “things aren’t adding up” with deal being pursued by Port of Cascade Locks and tech startup

Loud but how clear? Stephen D. King addresses Cascade Locks residents at a March 15 open house inside the Flex 6 building. The bullhorn was provided by one of the locals who expressed concerns over the proposal for a new data center inside the building. Photo: Nathan Gilles

By Nathan Gilles. March 20, 2023. On a cold March night, over pints of beer and fried food, a group of about 45 concerned residents gather at a local brewery in Cascade Locks, Ore., to discuss the topic everyone’s been talking about: a proposal for the construction of a new “green” data center at the Port of Cascade Locks.

A month earlier, on Feb. 3, a tech startup few had heard of called Roundhouse had signed a Memorandum of Understanding with the Port of Cascade Locks to build the new data center.

The agreement is the beginning of a process that could end with Roundhouse signing a 25-year lease on a vacant industrial building called Flex 6 on the banks of the Columbia River. The agreement could also lead to Roundhouse leasing an additional 10 acres of adjacent Port property to construct a second building for its data center project.

According to its MOU with the Port, Roundhouse would pay the Port rent for the Flex 6 building starting at a discounted rate of $22,500 a month.

Rates would increase over time, averaging about $49,000 a month over the 25-year lease, according to reporting in The Oregonian.

Building the second facility on the empty lot would provide additional funds. The land would be leased to Roundhouse starting at $450 per acre per month, eventually reaching $2,000 per acre per month, according to the MOU.

Vacant promise: The Flex 6 building in Cascade Locks remains unoccupied. Photo: Jurgenhessphotography

But these details are only part of the story.

Stephen D. King, the man who signed the MOU as Roundhouse’s CEO, was previously entangled in a business deal in Hood River County that led to a legal action against King; King’s owing over $1 million to former business partners; and an investigation by the state of Oregon into possible violations of Oregon securities laws by King.

In addition, two local businessmen say the idea for the data center didn’t originate solely with King. They say the plan was a joint effort between King and themselves, and they were surprised to learn King had pursued the data center in Cascade Locks without them.

It’s unclear how much the Port of Cascade Locks knew about King or his former business dealings before it signed the MOU.

Details about Roundhouse have been hard to come by, and details about the data center have been contradictory, according to some.

What’s more, according to numerous locals, Roundhouse and the Port of Cascade Locks have intentionally tried to keep knowledge of the new data center deal from the public.

“By and by the public has not been involved. The community has not been involved in this decision and it’s our time to get involved,” said Cascade Locks resident Carrie Klute at the March 1 event at the brewery in Cascade Locks.

Klute was one of the organizers of the event. She said she felt the Port has been withholding information from the public.

She’s not the only one.

Environmental, transparency concerns

A picturesque town of around 1,400 people, Cascade Locks is surrounded by the Columbia River Gorge National Scenic Area. Klute says the natural beauty of the region is why she and others choose to live in Cascade Locks.

It’s also why she and other local residents say they’re concerned about the potential environmental impact of a new data center.

Local interest: Carrie Klute organized a meeting of residents concerned about lack of information around the proposed data center. Photo: Nathan Gilles

Among numerous issues, Klute and others want to know if the new data center’s need for power will raise their electric rates.

They want to know if the center’s air-conditioning units and reserve generators will be noisy or cause pollution.

And the community that protested Nestlé when the multinational tried to bottle the town’s spring water wants to know how much water the data center will need to cool its many heat-producing computer processors.

But such environmental concerns were back-burnered at the March 1 meeting when Brad Lorang, vice president of the Port commission and a former mayor of Cascade Locks, refuted Klute’s claim that the Port was withholding information from the public.

He did so with a surprisingly frank admission.

“What I can say is the Port is not withholding information, because I have about the same amount of information that you have,” Lorang told the crowd.

In February, when the five-member port commission voted 4-1 to approve the data center MOU with Roundhouse, Lorang had cast the lone dissenting vote.

Lorang clarified his statement in an interview with Columbia Insight, saying he was concerned that the Port had not done its due diligence before approving its MOU with the company.

“It’s not that the Port is withholding the information,” said Lorang. “It’s more like the Port is taking it on faith that [the data center] is going to be the best for the community.”

Cascade Locks Mayor Cathy Fallon also told Columbia Insight she has concerns about the data center and about Roundhouse.

“If the whole entire city said they wanted the data center, by God, I would back them,” said Fallon. “I want to support the community. But things aren’t adding up with Roundhouse.”

Stephen D. King, Roundhouse, MYND

Though founded or co-founded by a Portland man named Stephen D. King, little public information is available on the company referred to in the Port of Cascade Locks MOU as Roundhouse Digital Infrastructure, Inc., and called simply Roundhouse or the Roundhouse Group in other Port documents.

As of the first week of March, neither Roundhouse Digital Infrastructure nor Roundhouse Group was registered with the Oregon Secretary of State Corporation Division. Nor was King’s name associated with any version of “Roundhouse” registered in Oregon.

A company called Roundhouse Group, Inc. was registered in Delaware and active as of 2019, but that state’s corporate privacy laws make it difficult to determine individuals associated with the company. It’s unclear whether the Delaware-registered company is the same Roundhouse that’s partnering with the Port of Cascade Locks, though Commissioner Lorang believes it is.

The domain name roundhouse.cloud, a web address associated with an email address used by King, is parked, meaning that it’s registered, but neither active nor connected to an online service.

Big deal: Stephen D. King inside the Flex 6 building in Cascade Locks where he hopes to locate a new data center. Photo: Nathan Gilles

Yet for all of this Stephen D. King is hardly an unknown figure in Oregon.

The 65-year-old King has been associated with multiple companies over the past two decades, according to information on King’s LinkedIn page, court records and business registration data listed in Oregon and California.

These include XOsphere, Direct Intelligence, Capital for Community, EmergentApps, Forge Vision, Visionary Assets, Isis Systems Group and Isis New Media.

In 2003, King and Isis New Media were sued by American Express Centurion Bank over a business account King had opened. King owed the bank $32,000, according to San Francisco County court records.

Isis Systems Group, which is registered in California under King’s name, is listed as “suspended” in California, according to the California Secretary of State website. The site lists the company’s standing with the secretary of state and the state tax board as “Not Good.”

According to company descriptions, King’s businesses have been engaged in providing “convergence marketing strategy and planning to organizations” and “global development, infrastructure and human innovation.”

King’s LinkedIn page states he holds a Bachelor of Arts in Anthropology from University of California, Berkeley. However, the University of California, Berkeley told Columbia Insight via email that King was admitted as a sophomore in Fall ’79, was undeclared, “attended for three quarters, and did not complete a degree.”

King’s business activities in Oregon began picking up in 2018. (From January 2009 until August 2018 his LinkedIn page lists him as president of Direct Intelligence, LLC, based in the San Francisco Bay Area. Direct Intelligence is listed as “suspended” in California. The company’s standing with the state tax board is also listed as “Not Good,” according to the California Secretary of State website.)

In 2018 and 2019, King began registering various companies using the handle “MYND” as part of the name, according to the Oregon Secretary of State website.

The numerous MYNDs associated with King include MYND Global, MYND Opportunity Fund I, MYND Wired, MYND Global Management, MYND Global Group and MYND Cascadia Marketplace I. There’s even a nonprofit MYND registered in King’s name called MYND Global Foundation.

As its names suggest, MYND has been full of big ideas.

According to myndglobal.com, MYND’s many areas of focus include: “Community Controlled Energy Grids,” “networks of locally owened [sic] grocery stores,” “Licensed Production Facilities” based on “modular systems that can produce everything from medicinal herbs and hemp CBD to wired Internet of Things (IOT) devices—all of which are marketplaces in the hundreds of billions of dollars.”

The website also says MYND focuses on data centers, specifically what the company calls “Municipal Data Centers.”

Michael Bergmann and MYND

It was these big ideas that attracted Michael Bergmann to start working with MYND. Following a 30-year career at Nike, Bergmann now heads IncubatorU, a corporate consultancy based in Portland.

But, says Bergmann, the attraction to MYND didn’t last long.

“A lot of their philosophical ideas I kind of agreed with, but it was a complete scam,” Bergmann told Columbia Insight about MYND. “I was inspired by the concept, but the more I dug into things, they didn’t add up. That’s really how it happened.”

Bergmann says he was hired by MYND in 2019 to help with an aquaponics facility that was planned to be built at a site called Dee Mill in Hood River, Ore. (Aquaponics is a form of indoor farming that combines hydroponics with fish farming.)

But the facility was never built.

Bergmann says MYND Global Group never paid him the full amount for the work he did.

Bergmann showed Columbia Insight documentation from a collection agency showing that MYND Global Group owes him $30,000.

“I always assume positive intent with everyone I work with,” says Bergmann. “But even early on I would get a partial check for the work I put in and then it bounced, and I was told ‘Just give it another week.’ The checks were hand-written from a bank. It’s like, ‘Really, dude?’”

But Bergmann says his experience with MYND pales in comparison to what happened to a friend of his.

“My friend, Kay O’Neill, trusted that her money [invested with MYND] would be put into an opportunity zone and there is no trace of it,” says Bergmann. “It was so sad, I felt so bad for her because she is such a good person.”

MYND, Dee Mill, Kay O’Neill

Kay O’Neill says she became involved with MYND and King in January 2019.

“I feel the very strong duty to tell my story to warn potential victims so that we can stop the damage that King has done to so many people,” O’Neill told Columbia Insight.

O’Neill is an independent consultant living in Portland.

The MYND project O’Neill invested in was the same proposed aquaponics facility Michael Bergmann had been involved with.

The facility was planned for construction in an opportunity zone at the Hood River Dee Mill site (named for a mill that once stood on the property).

Opportunity zones are sites that have been designated by the federal government for development to foster economic growth and job creation in low-income communities, according to the IRS. Opportunity zones also come with significant tax breaks for investors.

MYND’s website touted the company’s interest in “Aquaponics and Vertical Farming” as part of “an emerging food production segment called Controlled Environment Agriculture (CEA).”

The proposed Dee Mill aquaponics project would produce food locally, according to myndglobal.com and company promotional material. The food would then be distributed throughout the region via MYND Cascadia Marketplace.

“It was a great idea,” O’Neill now says about the project.

Excited about the possibilities, O’Neill says she became the project’s primary investor, someone who would front the money to purchase the opportunity zone land at the Dee Mill site.

O’Neill says she was then hired by MYND to do workforce development to ensure that the jobs the project created went to local residents.

“That was a primary hook for me, because then you make sure the jobs went to people in the community,” says O’Neill, who is currently board president at Roots of Success, a nonprofit that specializes in job training programs in communities with high unemployment and poverty rates.

O’Neill says she lost $883,401.96 of her $972,401.96 investment with MYND. The other $89,000 went to taxes, according to O’Neill.

O’Neill showed Columbia Insight banking documents and letters signed by King showing that she had invested in MYND Global Group via MYND Opportunity Fund I. A letter dated April 5, 2019, lists King as manager of the MYND Opportunity Fund.

According to O’Neill, King moved her opportunity zone investment into an escrow account as earnest money to purchase the Dee Mill property.

But the aquaponics facility never got built because the Dee Mill property was deemed to be unsuitable for the project.

MYND website screen shot from March 20, 2023. Text in part reads: “The Dee Mill property is an ideal headquarters for the Cascadia Marketplace because of its central proximity to other parts of the region. This project is also a partnership between MYND and InCity farms to bring a state-of-the-art aquaponics and vertical farming facility to the Mount Hood area.”

What’s more, the site itself was a point of contention with Hood River environmental activists, who had worked to block previous projects at the site.

O’Neill, deciding the site was a bad investment, asked King for her money back in the fall of 2019. But, she says, King refused to terminate the real estate purchase.

“I told Stephen [King] you have got to terminate this contract,” O’Neill now says. “He told me to talk to his lawyer.”

“In less than a year, he disappeared all the money,” says O’Neill. “Ultimately, Stephen [King] squandered the entire investment Initially, I thought King was an incompetent businessman. I made a mistake trusting him and I attempted to recover as much of our investment as possible.”

“King is such a good con artist,” O’Neill continued. “He would make you think he was working for you. He would say that with me, ‘I’m working for you. I’m going to get your money back.’ King would say, ‘I’m helping to make you whole. I’m doing this for you.’”

Following her time at MYND, O’Neill filed a complaint against King and MYND Global Group with the Oregon Department of Consumer and Business Services Division of Financial Regulation claiming that King and MYND had violated Oregon securities laws.

The state of Oregon opened an investigation into King and King cooperated, according to a letter sent to King by the state’s lead investigator and obtained by a Columbia Insight public records request.

The letter, dated July 21, 2021, states that the Division of Financial Regulation “will not pursue further action at this time, and have closed the file [on MYND Global Group and King].”

After the investigation, O’Neill chose not to take legal action against King.

But another investor did, suing King and MYND Cascadia Marketplace I for breach of contract, according to court records filed in Multnomah County, Ore.

In a judgment against King, King was ordered to pay the investor $283,872 at a 12% interest rate. The investor, who is associated with a business in Palo Alto, Calif., could not be reached for comment.

MYND, In City Farms, Glenn Ford

The website myndglobal.com calls the Hood River Dee Mill project “a partnership between MYND and InCity Farms to bring a state-of-the-art aquaponics and vertical farming facility to the Mount Hood area.”

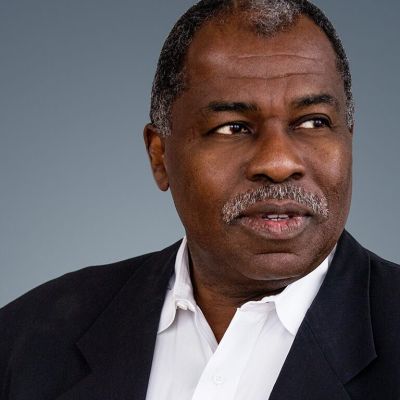

Glenn Ford, founder and CEO of the Minnesota-based aquaponics company In City Farms, says this statement is misleading. Ford is a well-known proponent of the new agricultural technology.

Aquaponics advocate: Glenn Ford. Photo: TEDxMinneapolis

“Stephen [King] should make no claims about connections with In City Farms,” said Ford, when asked why his company is listed as a partner on the MYND website. “That absolutely should not occur, and I will have to mention that to my attorney.”

Ford said he once did business with King and MYND, but no longer wishes to be associated with either.

Ford confirmed he had worked on two projects with King, the Dee Mill project in Hood River and one in Duquesne, Penn., that also was never completed, according to Ford and other sources.

Ford said he cut ties with King for reasons he couldn’t disclose due to legal concerns, saying only, “I lost confidence in his words.”

“My recommendation to anyone doing business with Stephen [King] is run,” said Ford.

Tiny homes in Cascade Locks

After the Dee Mill aquaponics project appeared no longer viable, King began working with the Port of Cascade Locks, though not immediately on the current Roundhouse data center idea.

The first project King pitched to the Port had to do with affordable housing.

During a Port commission meeting held on Aug. 4, 2022, King, saying he represented a group called Resilient Habitats, presented the Port of Cascade Locks with a business proposal to manufacture “tiny homes” at the Port’s Flex 6 building.

A Resilient Habitats, LLC is registered in Wyoming, though it’s uncertain whether this is the same company King was representing, given the state’s strict corporate privacy laws.

According to Port commission meeting minutes, King told the commission that Resilient Habitats’ “overall vision is helping communities.” To that end, King said Resilient Habitats had spoken with “Skamania, The Dalles and Dallesport, to identify housing needs as well as commercial needs.”

Resilient Habitats’ proposal included a mention of Worldwide Structures, a Native American-owned company based in Monterey, Calif. “that provides the structural elements to our habitats,” according to documentation obtained by Columbia Insight

But that company did not provide the service King claimed, according to Worldwide Structures CEO Rick Novack.

“No, that’s the pretty quick answer, no,” said Novack when asked if his company provided structural elements for Resilient Habitats. “I have never done any business with them that I know of.”

When asked if he knew Stephen King, Novack responded, “Yes, I do, unfortunately, I do.”

But Novack declined to elaborate on his relationship with King.

“I won’t do business with Mr. King, let’s leave it at that,” Novack told Columbia Insight.

Data center origins

Once the idea of tiny homes from Resilient Habitats lost momentum, King began pitching a new idea for the Flex 6 site: a data center.

At an Oct. 27, 2022, Port commission meeting, King, now representing a business called the Roundhouse Group, pushed for the construction of a new data center, according to a video of the meeting posted to YouTube.

This wasn’t the first time a data center had been discussed at the Port of Cascade Locks.

An Oregon company called EdgeSite, registered to Dr. Jerald Kyle House, a pediatric dentist in Hood River, had previously gone to the Port to discuss a data center project. EdgeSite is currently building a data center in The Dalles, Ore., according to House.

When asked if he knows Stephen King, House was blunt.

“He owes me money,” House told Columbia Insight.

In a subsequent email, House sent a copy of a promissory note dated Dec. 1, 2019, showing that King and MYND Cascadia Marketplace I owed him $50,000. The total amount King owes House is $100,000, according to House.

After a previous deal between House, King and MYND had soured, House says he continued working with King on his (House’s) plans for a data center. House said he wanted to give King a second chance to earn back the money he owed him.

“I was giving him [King] an opportunity to not be in default, so I wouldn’t have to go to the DA and charge him for fraud,” said House. “I hoped he would be a bit of a redemption story.”

“The value to Cascade Locks of this project [data center] is astronomical.” —Stephen King

House’s connection to the newly proposed Cascade Locks data center is complicated.

When informed by Columbia Insight that King had signed an MOU with the Port of Cascade Locks to build the data center, House was surprised.

“They’re doing what?!” asked House.

House said he wasn’t aware that King had been pitching projects under the name Roundhouse or Resilient Habitats. He said he hadn’t communicated with King since July 2022, before King gave presentations on either project.

House said he found the situation “troubling” because Roundhouse and the data center were ideas he had developed with King and longtime business partner Doug Kirchhofer under a group called KYDO.

“KYDO” is a combination of the names “Kyle” and “Doug.”

When asked if he knew that King had signed the MOU with the Port under the name Roundhouse Digital Infrastructure, House responded: “He’s changed the name, that’s not going to hold up in court.

“For him [King] to think he’s just going to wander into the Gorge where all of us live, where all of us are very engaged in our community, and that this would all just slip under the radar and some data center was going to be built by Stephen King and no one was going to notice and ask for their money back?”

House also said King’s design for the data center looked very similar to the one he, King and Kirchhofer had worked on together.

“We dialed this thing down to a business plan, which we presented to the Port,” said House. Doug [Kirchhofer] and I looked at it [Roundhouse’s data center plan] and said, ‘well, that’s our plan.”

Doug Kirchhofer confirmed House’s story to Columbia Insight, saying KYDO had designed and discussed building a data center for the Port with King. But he said prior to being informed by House, he’d had no idea King had presented the idea to the Port.

“What he’s been doing for the last seven months is nothing that Kyle [House] and I are involved with,” said Kirchhofer. “We have had zero knowledge of what’s been happening.

“For us not to be involved is concerning for me because we don’t want out names associated with something we’re not involved in. … The Port of Cascade Locks have not talked to us for months, so they must be fully aware that we are not involved with him [King] either.”

“Doug and I developed the data center project. All of sudden it’s coming back, exactly, exactly, the way we detailed this project.” —Dr. Jerald Kyle House

According to House, Resilient Habitats was also his and Kirchhofer’s idea.

“Doug [Kirchhofer] and I’s full deal was to build affordable housing in the Gorge,” said House.

House says he still wants to manufacture affordable housing locally in the Gorge and he hopes to work with Worldwide Structures to do it.

House and Kirchhofer are both investors in CEO Rick Novack’s Worldwide Structures. Novack says he thinks highly of both men.

“We have had a long relationship with those two gentlemen [House and Kirchhofer] and very favorable. They are both very reputable individuals,” said Novack.

What the Port knew

It’s unclear how much the Port of Cascade Locks commissioners and staff knew about King and his business history before signing the MOU for the data center.

Mark Johnson, the Port’s government relations consultant, told Columbia Insight he’d never heard the name MYND and that he didn’t know that King had been investigated by the State of Oregon for securities violations.

When asked if King’s Resilient Habitats affordable housing pitch was done on House and Kirchhofer’s behalf, Johnson said he didn’t think so.

“I don’t believe he was representing House at the time,” said Johnson. “I haven’t had any interactions with Kyle [House] really, the Port hasn’t had any official interactions with Kyle in quite some time.”

When asked if the Port had looked into King and his past business dealings, Port President Jess Groves responded: “We’ve looked into things pretty thoroughly.”

According to Port documents obtained by Columbia Insight, House, Kirchhofer and King were communicating with the Port as recently as May and June of 2022. Documents show the three men working together under the name KYDO and Resilient Habitats and actively seeking an MOU with the Port to build affordable housing.

Port’s financial situation

The $6.5 million Flex 6 building was constructed for a previous Port tenant that declared bankruptcy shortly after the building was completed. Lying empty, Flex 6 currently costs the Port $38,000 a month, according to Port Vice President Brad Lorang.

Lorang also told Columbia Insight that the Port is too dependent on tolls from the Bridge of the Gods (which spans the Columbia River, connecting Oregon and Washington) to fund its budget. Federal rules require that the Port stop this practice by 2030. On top of this, the Port has been holding money in contingency due to a racial discrimination lawsuit filed in November 2021, according to Lorang.

These financial problems were discussed in detail at the community meeting held on March 1.

But it’s the data center in particular that’s drawn attention from residents.

Revenue stream: The Bridge of the Gods is Cascade Locks’ most well-known landmark. And a budget boon. Photo: Di Manickam/Unsplash

Several Cascade Locks residents told Columbia Insight that the Port of Cascade Locks has tried to keep details of its deal with Roundhouse from leaking to the public.

As proof, they point to a video posted on YouTube from the Oct. 27, 2022, Port of Cascade Locks Commission meeting when King first proposed the data center. During the meeting, Port President Groves had a message for anyone attending the meeting on Zoom.

“I do want to put out a caution to everyone that’s on the Zoom call,” said Groves. “We normally have these kind of presentations in executive session. This is a commission-led decision and we don’t really want somebody [King] who is proposing a big deal like this [data center] to the Port for this to be out in the public for public conversation until the commission makes decisions on our direction.” [The comment begins at the 51:09 mark of the previously posted Youtube video.]

Asked about his comment, Groves said Roundhouse’s proposal never should have been discussed in a commission meeting, which is open to the general public. Instead, he said policies set by the Port’s attorney dictate that discussions with business clients should be held in executive session due to confidentiality concerns.

“I was a little bit upset that these people were on the Zoom call basically,” said Groves.

“This [executive session] is a standard procedure for the Port when we work with clients until we are ready to bring things forward like this [proposed data center],” said Groves.

Stephen King responds

On March 14, Stephen King agreed to an interview with Columbia Insight.

During the 30-minute interview, King was open and amiable. His political affiliations are decidedly left-leaning. King also seems genuinely concerned about environmental issues.

King said in the past he’s had business dealings with Oregon Public Broadcasting, the Natural Resources Defense Council, Sierra Club and Sierra Club Legal Defense Fund (now Earthjustice)

In a follow-up email he wrote that he’d also worked with Greenpeace and written for the The Nation.

King denied Kirchhofer and House’s claim that the two men did not know King was representing them in his current dealings with the Port.

When asked if he owed House money, King said: “Businesses all start with money. Yes, of course, I never said I didn’t [owe House money].”

King told Columbia Insight In City Farms founder and CEO Glenn Ford owed him money and called into question Ford’s business abilities. King showed Columbia Insight a promissory note dated Sept. 1, 2020, to support this claim. In a follow-up email, King added: “He’s [Ford] trying something hard and I wish him all the luck in getting his project done.”

When asked about the money Kay O’Neill invested in MYND’s Dee Mill project, King said: “That money is being applied to this project [Cascade Locks data center].”

King said the Dee Mill project failed because “we weren’t able to finish the financing on that.”

King said he intends to use anticipated funds from the Cascade Locks data center project to repay O’Neill, House and others he owes money to. King said this had always been his intention.

King said he would provide Columbia Insight with dated legal documentation supporting this statement. [Columbia Insight will update this story upon receipt of such documents. —Editor]

“The value to Cascade Locks of this project [data center] is astronomical and I want Kay [O’Neill] to get absolutely all of her money back,” said King. “This project will make her way more money than that original project.”

When asked about the State of Oregon investigation into MYND and the Dee Mill project, King said: “The state of Oregon looked into it and found that there was no issue. … It was investigated, and nothing was found.”

Troubled waters? Cascade Locks is located within the Columbia River Gorge National Scenic Area. Photo: City of Cascade Locks

King said he thought the new data center would be a good fit for Cascade Locks, adding via email that the data center could create 40 to 60 jobs.

During our March 14 interview and a follow-up interview the next day, King highlighted other benefits the data center could have for Cascade Locks, including financial benefits to the Port and City of Cascade Locks.

In documentation presented to the Port by King, Roundhouse has stated that it plans to profit share with the Port. Roundhouse also plans to return 25% of its enterprise zone tax abatement to the community of Cascade Locks, which over 10 years could lead to $4.5 million, according to King. Roundhouse, which will purchase power from the City of Cascade Locks, estimates it will increase the city’s revenue by $1.5 million.

And, said King, Roundhouse’s data center will meet industry standards to qualify as a “green” data center, and not just because most of its electricity will come from hydroelectric power.

“We’re positioning this as probably one of the greenest data centers in the country,” said King. “Part of that, of course, is where the power comes from in Cascade Locks [hydropower], but it’s also our particular design. It’s incredibly efficient.”

King said the data center would be used in the fight against climate change, saying that the data center’s clients will include groups who are working on redesigning and upgrading power grids.

“All that requires a huge amount of data center computational capacity,” said King. “So, from our perspective, we’re really ushering in the new energy regime in terms of climate change.”

But environmental concerns remain. The big one is water.

How much water?

In a follow-up conversation, House, who by then had reviewed many of the details of King’s proposed data center, said he couldn’t find faults with the project’s design, because it is essentially the same project he and Kirchhofer had previously wanted to build at the Port.

“Doug and I developed the [data center] project,” said House. “We introduced him [King] to Cascade Locks, introduced him to the data center people. We walked him down our data center path. And all of sudden it’s coming back, exactly, exactly, the way we detailed this project.”

These details, according to House, include the use of a closed-loop system that relies on a proprietary coolant to directly cool the data center’s processors, something EdgeSite plans to use in its data center in The Dalles.

This cooling system, says House, generally uses less energy and produces more computing power than systems that rely on water and air for cooling.

House said he knew water is a “big deal” in the Gorge. For this reason, he said he and Kirchhofer intentionally designed their data center to rely on the closed-loop coolant system because such a system doesn’t require the constant use of new water.

However, the Roundhouse data center might not be the data center House intended.

At a March 15 open house at the empty Flex 6 building, Cascade Locks residents finally got to meet the people behind Roundhouse and the data center.

In front of a crowd of about 100 people, King and several other members of Roundhouse described how the data center would work and how it would benefit Cascade Locks.

“From our perspective [this is] probably the greenest data center in the country. It has a very small footprint,” King told the crowd.

Looking for answers: Cascade Locks Mayor Cathy Fallon. Photo: Nathan Gilles

During the open house, many local residents raised concerns about water, which is expected to be used to help cool processors.

To address these concerns, James Longacre, Roundhouse’s chief operating officer and chief engineer, asked for four people in the crowd to stand up.

“This facility, this facility will use less water than those four people will consume in this year and that’s in the same year,” said Longacre. “Six gallons an hour, 90,000 gallons a year and I don’t even think we need to use that much.”

Longacre said the system would also use outside air to cool the data center.

This, however, is not the cooling system King pitched the Port before it signed its MOU.

At the Feb. 2, 2023, Port commission meeting, the day before the MOU was signed, King told the Port Commission that the Roundhouse data center would use a “closed-loop cooling system, meaning the coolant to cool the servers is completely closed and that there is no migration of refrigerant,” according to meeting minutes.

The closed-loop system has since been dropped in favor of the system described by Longacre.

At the March 15 open house, Cascade Locks Mayor Cathy Fallon told the crowd she only learned about the change in the cooling system because she read a March 11 article in The Oregonian, which makes no reference to a closed-loop system or coolant.

The article states the data center “expects to rely heavily on atmospheric cooling in windy, rainy Cascade Locks to chill its computers.”

“There was a potential that we would have used a system that used no water but used a refrigerant,” said King in response to Fallon. “Instead, we used this solution which literally uses four people’s worth of water.”

Community members fed up

Concerned about the Port’s leadership and its current dealings with King, some Cascade Locks residents have decided to challenge both.

At the March 15 open house at Flex 6, some locals held up signs reading, “Water is Priceless” and “LOCKS NOT FOR SALE.”

Others have chosen to challenge the Port in other ways.

David Lipps, owner of Thunder Island Brewing and a former Port of Cascade Locks commissioner, says he plans to file a recall for both President Groves and Commissioner Joeinne Caldwell.

“We are recalling Jess Groves and Joeinne Caldwell for making careless decisions as elected port commissioners. We have been left in a vulnerable financial position under their leadership, and our community needs leaders we can trust,” wrote Lipps in an email to Columbia Insight.

“That’s up to the community,” said Caldwell when told about the recall. “If they want to recall me they absolutely have the right to do that.”

“I don’t know. So, I hear,” was Groves’ comment about the recall.

Winter of discontent: Cascade Locks residents expressed concerns about the data center plan and port commission transparency at the Roundhouse/Flex 6 open house. Photo: Nathan Gilles

Another resident hoping to instigate change at the Port is Carrie Klute, who helped organized the community meeting in the brewery on March 1.

“I see an opportunity for more transparency and engagement from the Port, which is why I decided to run for one of the Port commissioner positions, to truly be a voice for the community,” wrote Klute in an email to Columbia Insight.

During our March 14 interview, King told Columba Insight that some but not all Cascade Locks residents who were against the data center included “this fringe set of people who were against it in my perspective.”

In our second interview King compared some community member’s ideas to those of “QAnon.”

As of this story’s publication, it’s unclear if King or the skeptical residents of Cascade Locks will win the day.

The post EXCLUSIVE: Businessman proposing data center on banks of Columbia River has history of troubled deals appeared first on Columbia Insight.

EXCLUSIVE: Businessman proposing data center on banks of Columbia River has history of troubled deals was first posted on March 20, 2023 at 4:18 pm.

©2022 Based in Hood River, Oregon, Columbia Insight’s mission is to publish original, balanced journalism about environmental issues affecting the Pacific Northwest. Columbia Insight is a fully independent, registered nonprofit organization. To support environmental journalism “donate here” to Columbia Insight.