Why does the public put up with corporate welfare, wildlife slaughter and other government policies it so clearly opposes?

Subsidy city: Politics haven’t kept pace with majority opinions on public lands. Photo illustration: Nicole Wilkinson

By Nick Engelfried. July 11, 2024. With a little imagination, Douglas Creek Canyon near the central Washington town of Palisades can call to mind the Inner Northwest before colonization.

Orange and yellow lichens encrust the basalt canyon walls. Sagebrush clings to the lower slopes, especially those too steep for people or livestock to reach easily. Cottonwoods and willows form a green corridor along the creek itself, which carved out the canyon over centuries.

Goldfinches sing from treetops while turkey vultures soar over cliffs.

Prior to colonization, the bio-diverse shrub-steppe of which Douglas Creek Canyon is part covered almost a third of Washington, creating habitat for animals like pygmy rabbits and sage-grouse that are now at risk of extinction.

Elk and pronghorns grazed native bunchgrasses and were hunted by wolves.

Today, a fraction of this ecosystem is left intact.

Over two-thirds of the shrub-steppe has been destroyed, mostly by agriculture, while much of what remains is degraded.

Many casual observers don’t notice the damage precisely because it’s so ubiquitous.

“Most Western lands are now so degraded, the average American thinks that’s what they’re supposed to look like,” says Erik Molvar of the Idaho-based Western Watersheds Project. “But when the first white explorers arrived here, they recorded grass growing up to their horses’ bellies, not the desertified remnants of those ecosystems we see today.”

Erik Molvar. Photo: Western Watersheds Project

Compared with many parts of the shrub-steppe, Douglas Creek is in fair shape. In places, sagebrush intermixes with rabbitbrush and bitterbrush, members of the native shrub community.

But many gentler canyon slopes are covered in invasive cheat grass. In some areas, almost no native plants grow.

Given time, and the removal of pressures like livestock grazing, this spot could revert to something like its pre-colonial state.

Perennial grasses could return, making shade that inhibits cheat grass. Sagebrush could spread into gullies where it’s now absent.

Tall grass and shrub communities would create animal habitat while discouraging wildfires.

Perhaps most importantly, the deep roots of native plants would pump tons of carbon underground.

Millions of acres in the dry West, much of it on public lands, are similarly ripe for restoration, with big payoffs for wildlife and the climate.

Yet, federal and state agencies funnel money into programs that actively inhibit natural processes in these places.

From subsidizing grazing to exterminating predators, taxpayer dollars support private interests at the behest of ranchers and agribusiness.

“The livestock mafia has set itself up for business in the West,” says Molvar. “And it’s become a political machine that’s very good at perpetuating its interests on public lands at the expense of other uses.”

Taxpayer-funded killing

Wolves in the Inner Northwest. Beavers on agricultural lands. Historically important salmon streams.

Each of these is an animal or ecosystem adversely affected by taxpayer-funded programs that support agricultural interests.

There are numerous ways government actions benefit cows, sheep and crops. But one of the most direct is killing wild predators who interfere with livestock.

“Since the first European settlers set foot on this continent, they viewed predators as a threat to species humans hunt for game or raise for food,” says Camilla Fox of the California-based Project Coyote. “Public attitudes, science and ethics have evolved since then, but federal practices and policies haven’t kept up.”

In 2023, the federal agency known as Wildlife Services killed over 375,000 native wild animals, according to the Center for Biological Diversity.

Photo illustration: Nicole Wilkinson

These included tens of thousands of coyotes, hundreds of cougars and black bears, and 305 gray wolves, a species that remains endangered over much of its range.

Most of this taxpayer-financed carnage takes place far from the public eye.

“The vast majority of people have never even heard of Wildlife Services,” says Fox. “Of those who have, many confuse it with the Fish and Wildlife Service.”

While the USFWS works to restore endangered species, Wildlife Services deals with conflict between people and animals, often by killing the creatures in question.

“Wildlife Services’ role is not to manage wildlife populations, but to minimize damage caused by wildlife,” the agency told Columbia Insight in an email. “Wildlife damage management protects resources and safeguards human health and safety in a responsible and accountable manner.”

Still, critics say Wildlife Services, which is part of the U.S. Department of Agriculture, too often bends to the farming and livestock industries.

“Having a federal agency whose mandate is to mitigate friction between wild animals and livestock creates a conflict of interest,” says Fox. “Its main stakeholders are ranchers and farmers raising livestock in places where there are wild animals. That creates a built-in structure giving agribusiness an outsize influence.”

Wildlife Services doesn’t only kill predators. It also takes out birds that feed on grain and beavers whose dams are unwelcome by landowners.

In 2019, the agency killed over 360,000 red-winged blackbirds.

Traps set for predators may kill or maim pets and endanger people.

A notoriously opaque agency whose activities are difficult to track, Wildlife Services exemplifies how government programs can serve small groups of stakeholders at the expense of public resources.

However, some of the most managed animals in the Pacific Northwest now fall under the jurisdiction of not the federal government, but states.

This is increasingly true when it comes to one of the country’s most contentious predators: wolves.

Wolf politics

In 1947, a hunter collected a state bounty for shooting the last known gray wolf in Oregon.

The species was already virtually extirpated from Washington, and not until the 2000s would wolves start making their way across the Idaho border to re-establish themselves in the two states.

Soon after, Oregon and Washington created state-run apparatuses dedicated to preventing wolves from preying on livestock.

Jay Shepherd. Photo: Conservation Northwest

“It started with just trying to keep track of their whereabouts,” says Jay Shepherd of the Bellingham, Wash.-based nonprofit Conservation Northwest, who worked for the Washington Department of Fish and Wildlife when the first wolf was confirmed to have returned to the state in 2008.

Shepherd was assigned to monitor the animals in eastern Washington.

“Then we started getting calls from people saying they saw a wolf, or one attacked their dog,” he says. “Some of it was just nervousness. But as time went on there were conflicts, especially with cattle.”

Wolves in western Washington are listed as endangered by USFWS, which plays the lead role managing their populations there.

But in the eastern third of Washington, where most packs occur, wolves have been federally delisted and are now managed entirely by the state.

The scale of resources devoted to keeping wolves from livestock speaks to how agricultural interests determine the contours of debate about wildlife, partly by tapping into culture wars grounded less in economics than an idealized image of the past.

“There’s this prevailing romanticism of the cowboy myth in the West, and a desire to keep it alive by supporting ranching,” says Western Watersheds Project’s Molvar. The cowboy era, when large cattle drives occurred across much of the West, is generally considered to have lasted from about the end of the Civil War into the late nineteenth century. “Ranching has borne little resemblance to it since. The cattle industry plays the myth for all it’s worth, though, because of the political benefits.”

Livestock interests’ ability to align themselves with a fondly remembered era has helped cement a base of support beyond those who benefit directly from ranching.

“Early on after wolves returned to Washington, we encountered lots of really angry people,” says Shepherd. “Some weren’t even involved with agriculture themselves, but still wanted to vent about wolves.”

As packs became re-established, many ranchers came to accept wolves’ presence, even if grudgingly. Today Shepherd rarely encounters the kind of vitriol stirred up when wolves first reappeared in the state.

However, WDFW still puts immense effort into preventing wolf-cattle conflicts.

“Our focus is on nonlethal deterrents,” says Seth Thompson, assistant regional wildlife program manager for WDFW.

Camilla Fox. Photo: ProjectCoyote.org

Methods the agency promotes include flashing lights and flagging used to scare predators away from cows. In many cases, ranchers pay to install deterrents on their land, while more expensive equipment may be supplied by the state.

Range riders, often employed by nonprofits, also help by scaring wolves away from cattle.

These strategies are largely effective. But when depredations do happen, wolves can be killed.

“To go lethal, there need to have been at least two nonlethal deterrents in place before a depredation occurred, and at least three depredations in 30 days or four in 10 months,” says Thompson.

Last year, WDFW authorized killing two wolves for preying on cattle. Another was killed in the act of hunting livestock.

Wolves are not, by any measure, a major source of livestock mortality.

Washington has around 1.17 million cows, of which 13 were confirmed or suspected to have been killed by wolves in 2023.

The predators are also believed to have killed two miniature donkeys and one alpaca.

Still, for some people wolves symbolize tensions between private interests and wildlife conservation.

This can obscure the fact that while large predators are a visible casualty of agribusiness influencing the management of public resources, they’re arguably not the most important.

“Cattle have an extensive presence on public lands,” says Shepherd. “There are lots of reasons to be concerned about that, and focusing solely on wolves means wolves will take the brunt of people’s anger. And the truth is, other impacts from livestock may be even more crucial.”

Socialist ranching

“Before colonization, the Inner Northwest was much more ecologically productive than now,” says Molvar. “You had seas of sagebrush mixed with tall perennial bunchgrasses providing habitat for species like sage-grouse.”

Visual cover from shrubs and native grasses gave sage-grouse and rabbits a refuge from predators. These small creatures formed a link in a food web that included animals from wolves to elk.

When cattle and sheep arrived, they razed perennial grasses, creating openings for invasive, highly flammable cheat grass.

Sheep move through public lands near Shoshone, Idaho. Photo: BLM

Meanwhile, the hooves of livestock destroyed natural soil crusts that inhibit weeds from germinating.

Cows wade in streams, causing erosion and polluting salmon habitat.

And livestock consume native plants at a rate that’s unsustainable in a dry landscape.

“An average public lands grazing lease authorizes livestock to remove 50-60% of available forage in a year,” says Molvar. “That leaves behind a degraded ecosystem.”

This grazing is heavily subsidized by taxpayers, with ranchers paying as little as $1.35 per month to keep a cow and calf or five sheep on BLM land.

By contrast, last year’s average monthly grazing rate for private lands was $16 in Washington and $19 in Oregon.

Nor do livestock on public lands benefit consumers by significantly lowering meat prices.

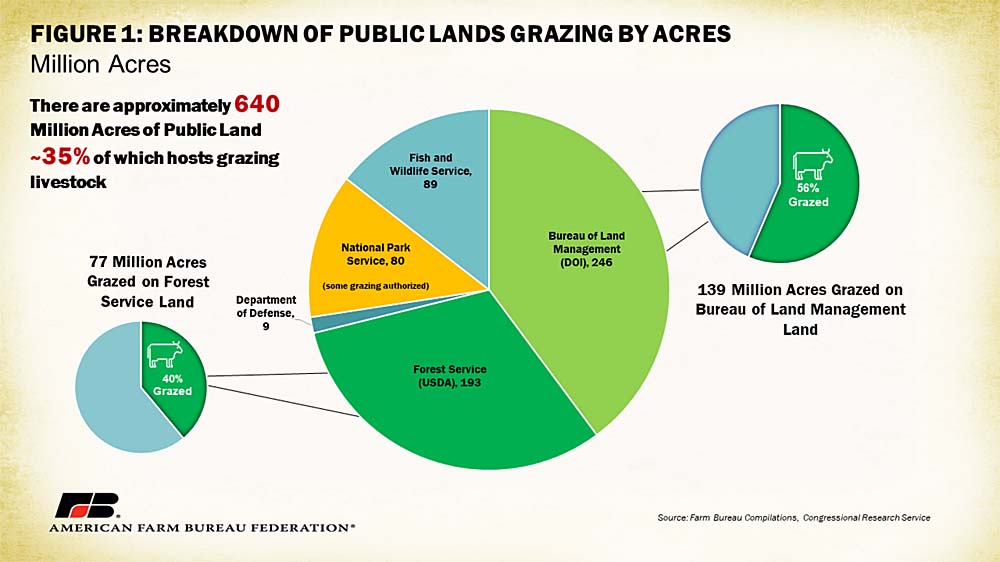

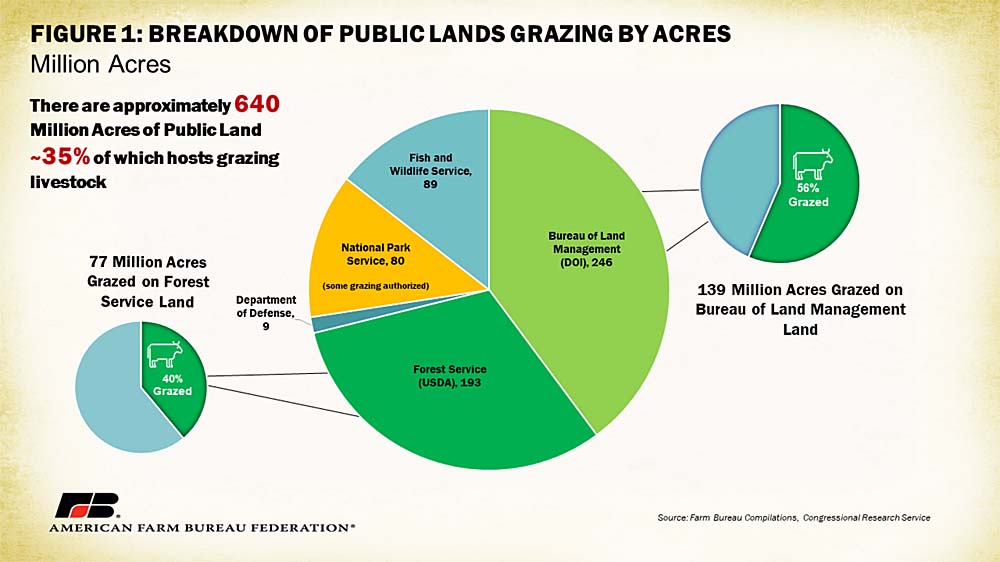

A paper in the peer-reviewed journal Environmental Management found less than 1.6% of grazing in the U.S. occurs on public land.

While this is a tiny percentage of overall meat production/grazing, the amount of public land being grazed is enormous—well over 225 million acres, according to the American Farm Bureau Federation. While they don’t manage as many acres for grazing as the BLM, the USFWS, Forest Service, National Park Service and Department of Defense also allow grazing on their lands.

“Very little beef is from cattle who set a hoof on public lands,” says Molvar. “Which raises the question, why allow grazing there, given the ecological impacts?”

Chart: American Farm Bureau Federation

The cattle industry claims grazing has a positive effect on the landscape.

“We always say ranchers are the original environmentalists, and we stand by that,” says Chelsea Hajny, executive vice president for the Washington Cattlemen’s Association. “There are a multitude of benefits to grazing, from reducing fire hazards to adding manure to the soil. We’re so prone to fire in Washington State, and cattle remove forage that otherwise creates fuel.”

Environmental groups dispute the notion that grazing reduces wildfire risk.

“Cattle are a number one cause of the cheat grass explosion, which has led to an increase in unnaturally large fires,” says Molvar.

By removing livestock from public lands, the United States could make progress toward the goal captured in the Biden administration’s America the Beautiful plan, of protecting 30% of the country’s lands and waters by the year 2030.

A 2022 paper in the journal Bioscience examined ways to help actualize this “30 X 30” goal by protecting core areas on Western federal lands. The authors identify livestock grazing as by far the largest direct threat to biodiversity in these places, with 48% of imperiled species there being affected.

The study recommends retiring existing grazing allotments.

It also suggests focusing on the restoration of two key species—gray wolves and beavers, both of which are targeted by agencies like Wildlife Services—whose activities in the ecosystem produce a cascading series of positive effects.

Washington’s Douglas Creek Canyon is the kind of landscape that could produce immense biodiversity and climate benefits if allowed to regenerate.

Not like it used to be: Douglas Creek Canyon. Photo: BLM

On both sides of the creek, barbed wire fences mark the boundaries of land that is or was formerly used for cattle, and the prevalence of cheat grass speaks to decades of grazing.

Some private land around the canyon is now protected.

For example, the Nature Conservancy’s Beezley Hills and Moses Coulee Preserves are located nearby.

However, the heart of the canyon is on BLM land.

In March, the BLM released a Greater Sage-Grouse Resource Management Plan that could limit grazing in the imperiled birds’ habitat across 10 western states, including Oregon. Washington is excluded because sage-grouse there occur mostly on private land.

Meanwhile, the BLM continues leasing land to ranchers throughout the West at rock-bottom prices, and agencies like Wildlife Services employ an approach to predator control resembling something from a previous century.

“The emphasis on lethal, indiscriminate killing of predators needs to change,” says Project Coyote’s Fox. “Not just from an ethical and humane standpoint, but based on what science tells us is effective. We need North America’s wild carnivores for healthy and diverse ecosystems.”

The use of public lands for subsidized grazing, and the continued persecution of wildlife, reflect an attitude on the part of responsible agencies that regards the public commons as a resource to be exploited by private business.

“One of most insidious ideas is that public lands should be viewed as agricultural land whose purpose is to maximize livestock production rather than ecological health,” says Molvar. “You have lands where cattle and sheep have become the dominant use, destroying wildlife habitat, recreational uses and the reasons the public values these places.”