The ‘Unprecedented’ Decline of a Wyoming Pronghorn Herd

Judge halves wolf trapping season to protect grizzlies

A federal judge has directed Montana Fish, Wildlife and Parks to cut much of Montana’s wolf trapping season in half due to evidence that traps and snares set for wolves unintentionally capture grizzly bears, which are federally protected under the Endangered Species Act.

In a 25-page order, U.S. District Court Judge Donald Molloy wrote that the Flathead-Lolo-Bitterroot Citizen Task Force and WildEarth Guardians established “a reasonably certain threat of imminent harm to grizzly bears should Montana’s wolf trapping and snaring seasons proceed as planned.”

Molloy directed the state to scrap its current season plans for most of the state in favor of more conservative start and end dates. The state’s Fish and Wildlife Commission in 2021 adopted a floating start date to provide some assurance that grizzly bears would be in their dens before traps and snares are set inside occupied grizzly bear habitat.

Molloy heard oral arguments on the conservation groups’ preliminary injunction request on Monday. The plaintiffs filed the lawsuit against the state of Montana, Gov. Greg Gianforte, and Montana Fish and Wildlife Commission Chair Lesley Robinson on Sept. 22.

FWP has recorded more than 20 instances of grizzlies being caught in traps set for other animals since 1988, and an expert for the plaintiffs has documented “numerous other examples” of such incidents, according to Molloy’s order.

Grizzly bear biologists have demonstrated an increase in the number of bears exhibiting “trap-like injuries” since wolf trapping was legalized, the plaintiffs asserted. Grizzly bear biologists noted that in 2021 alone, four different bears were missing body parts, including forelegs and toes, likely due to trapping. Other injuries that can arise from capture in traps and snares include limb fractures and dislocations, as well as tooth and gum damage.

“Each of these untoward events would violate [Section 9] of the ESA,” Molloy wrote, adding that “trapping or capturing an endangered species is an unlawful ‘take’ even if the action does not cause injury or mortality.”

Defendants countered that FWP’s floating start date in grizzly-occupied areas has reduced the likelihood of unintentional grizzly bear capture and injury. They also highlighted other protective measures the Fish and Wildlife Commission has adopted such as restrictions on snaring in lynx protection zones and requirements that trappers use breakaway devices on snares and check their traps every 48 hours.

The state argued that there have been no incidences of a bear caught in a public (i.e., non-research) wolf trap in a decade.

“While Defendants may be correct that there have been no confirmed reports of grizzly bears caught in recreational wolf traps in Montana since 2013, the precise harm at issue in this case has been well-documented in Montana and adjacent states and provinces that share the home ranges of Montana’s grizzly bear populations,” Molloy wrote.

“The Montana Fish and Wildlife Commission remains a clear and present danger to Montana’s carnivores and predators and we look forward to reining them in.”

Flathead-Lolo-Bitterroot Citizen Task Force President Patty Ames

The plaintiffs had also argued that evidence suggests grizzlies are likely to be out of their dens through more of the winter and that trend will only increase as climate change brings warmer winter temperatures to the region.

In an emailed press release cheering the order, the plaintiffs expressed optimism that they’ll prevail on the larger issues in the lawsuit as the case proceeds.

“We are pleased with this order and remain confident we will prevail on the larger merits of the case,” Patty Ames of the Flathead-Lolo-Bitterroot Citizen Task Force said. “The Montana Fish and Wildlife Commission remains a clear and present danger to Montana’s carnivores and predators and we look forward to reining them in.”

In a Facebook post, Gianforte argued that Molloy’s “sweeping order tramples the rights of trappers.”

“Montana has a healthy, sustainable population of wolves and grizzlies, and there has been no incidental takes of grizzlies from wolf trapping in Montana since 2013. And yet misusing ESA protections for the grizzly to thwart the state’s wolf management plan, the activist judge has obstructed the state from responsibly managing wolves based on the sound science of FWP biologists.”

Molloy’s order narrows the 2023-2024 season start and end dates while the lawsuit proceeds. Per his order, wolf trapping and snaring cannot begin until Jan. 1, 2024, and will end on Feb. 15 in FWP’s five westernmost regions. It also applies to Hill, Blaine and Phillips counties.

In areas in and near occupied grizzly habitat, the state had been set to open trapping season sometime between Nov. 27 and Dec. 31 and close it on March 15. The state said it will appeal the order.

The post Judge halves wolf trapping season to protect grizzlies appeared first on Montana Free Press.

Has Montana solved its housing crisis?

Group sues the Forest Service to halt trout replacement project in wilderness area

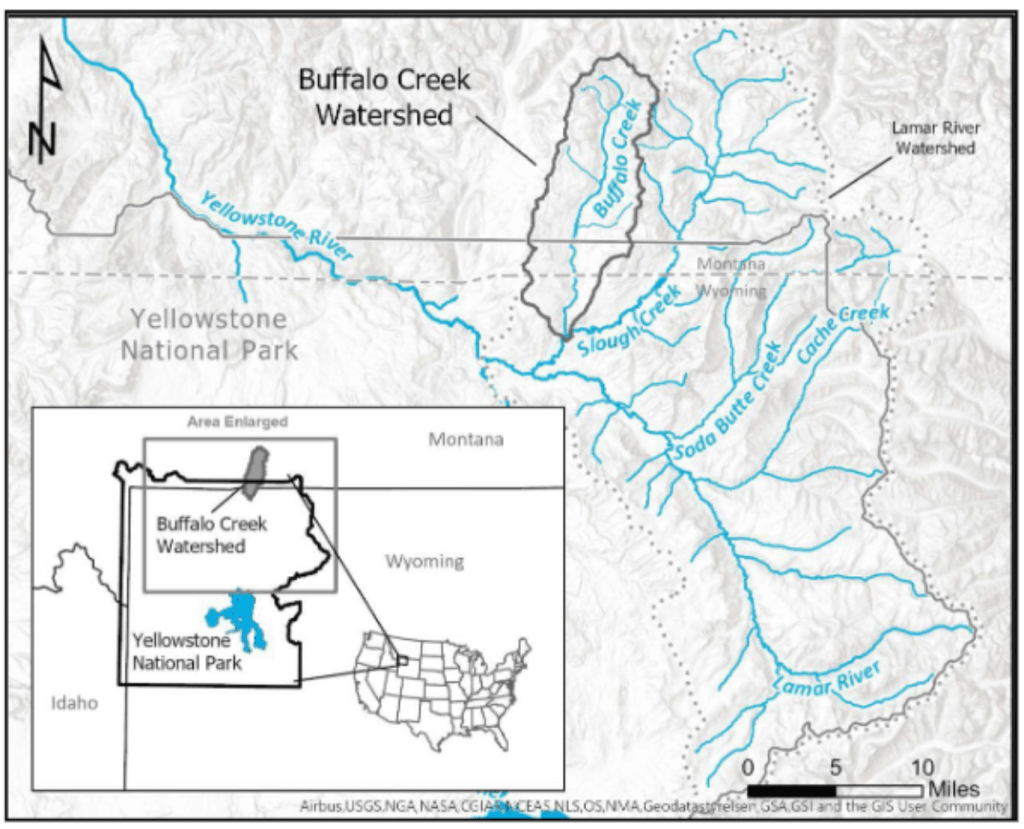

A Missoula-based nonprofit that advocates for wilderness conservation is pushing back on a Forest Service plan to poison 46 miles of waterways within the Absaroka-Beartooth Wilderness in an effort to clear them for Yellowstone cutthroat trout.

In a lawsuit filed in the U.S. District Court Nov. 8, Wilderness Watch argues that the Buffalo Creek project violates the Wilderness Act, which holds that wilderness areas should retain “primeval character and influence” and be “protected and managed so as to preserve [their] natural conditions.”

The Buffalo Creek project was authorized by the Custer Gallatin National Forest in August at the behest of Montana Fish, Wildlife and Parks, which seeks to expand Yellowstone cutthroats in waters beyond their native range to create a climate refuge for the fish as the waterways they’ve historically inhabited warm.

Hidden Lake and the upper reaches of Buffalo Creek are naturally fishless due to the area’s topography, but state wildlife officials have stocked rainbow trout in Hidden Lake since at least 1932. Now the state hopes to address the hybridization of rainbow trout and Yellowstone cutthroat trout in lower stretches of the watershed by applying rotenone to Upper Buffalo Creek and 36 acres of wetlands and lake surface, to create what Wilderness Watch describes as “an artificial reserve of Yellowstone cutthroat trout.”

Wilderness Watch Executive Director George Nickas described the plan as an attempt to “play God with species and habitat manipulation.” His group also takes issue with the expansion of motorized activity within the Absaroka-Beartooth Wilderness that the Forest Service has authorized for the poisoning and restocking project. Up to 81 aircraft landings and 60 days of motorized use have been approved to execute the plan.

“The Wilderness Act was passed precisely to rein in the propensity of managers to want to control nature. Our lawsuit seeks to preserve the wild character of the Wilderness and to let nature continue to evolve of its own free will,” Nickas wrote. His organization is asking courts to block the project, which is slated to begin next year.

In an April 2022 press release announcing the Forest Service’s support for the Buffalo Creek project, Gardiner District Ranger Mike Thom wrote that the agency was “poised to create secure cold water refugia and strongholds for the long-term sustainability and success of Yellowstone cutthroat trout.”

“This is one of those prime opportunities working jointly with Montana Fish, Wildlife and Parks to benefit the natural characteristics of wilderness with native fish communities critical to our ecosystem,” he continued.

The post Group sues the Forest Service to halt trout replacement project in wilderness area appeared first on Montana Free Press.

What Montana’s mayor-elects say they’ll do

A version of this story was originally published in the MT Lowdown, a weekly newsletter digest containing original reporting and analysis published every Friday.

New leadership is on the horizon for several of Montana’s large cities following municipal elections held across the state this week.

Voters in Missoula, Montana’s second-largest city, picked Andrea Davis as their first elected mayor since the death of longtime incumbent John Engen last year. Davis, executive director of the affordable housing nonprofit Homeword, won decisively over real estate broker and current Missoula City Council member Mike Nugent.

To the east in fast-growing Bozeman, the state’s fourth-largest municipality, voters made a rare decision not to hand incumbent mayor Cyndy Andrus another term, instead picking twenty-something progressive Joey Morrison over Andrus and environmental attorney John Meyer. (Bozeman’s commission system means Morrison will join the city commission for a two-year term as deputy mayor in January when current Deputy Mayor Terry Cunningham, who was elected two years ago, assumes the mayorship. Morrison will start his term as full-fledged mayor at the beginning of 2026.)

Great Falls, the state’s third-largest city, also picked new leadership, with former police detective and Cascade County Undersheriff Cory Reeves beating out a field that included former Democratic House Minority Leader Casey Schreiner.

Elsewhere in the state, Billings and Kalispell held city council elections but had their mayoral seats out of cycle this year. Helena’s election was limited to a down-ballot race in one neighborhood after the three incumbent commissioners who were up for re-election drew no challengers.

That’s a lot to keep track of, even without getting into results from smaller communities. As the MTFP newsroom talked about how to cover those results this week, we figured Lowdown readers would appreciate a chance to hear briefly from the fresh blood coming into some of the state’s most important local leadership roles.

All three of the big-city mayors-elect spoke to reporters by phone this week, discussing their plans for tackling, among other issues, housing affordability, homelessness and public safety. The interviews have been condensed and lightly edited for clarity.

Mayor-elect #1

Andrea Davis, Missoula

MTFP: How can Missoula add the housing it needs to accommodate a growing population without sacrificing the vibe that’s drawn people to the city to begin with?

Davis: When I first moved here, there was the 12th Street Grocery in my neighborhood. But because it was a nonconforming use, that little tiny corner grocery store went away. As we build our community out, how are we making it so we can access services, jobs, groceries, little restaurants on the corner without having to get in our car and drive across town and add to the congestion and add to the strife of the feeling of growth?

A lot of that will be how we make it so we’ve got mixed-use neighborhoods that are connected with well-functioning streets, that have sidewalks that allow people to move around. I really want to see us continue to advocate for and build out street trees. This I know sounds simplistic, but to me this is a very important part of quality of life for living in a city and also helps with the urban heat effect. And we’re going to need to be intentional about a mix of different home types.

MTFP: On the homelessness front, what’s your immediate game plan to make sure people without a place to live have the shelter they need this winter?

Davis: The city council has postponed the decision for an urban camping ordinance until Dec. 13. So my immediate game plan is to work with city staff, city council and the myriad of community partners as that ordinance gets considered against the other policies and practices that we have in our community. We have the Johnson Street facility that’s been opened and my understanding is there have been improvements to the operation of that facility. My immediate plan is to assess those operational procedures and make sure we’ve got a plan in place for a feedback loop with that neighborhood, because we heard loud and clear that that neighborhood felt they were not being heard.

Also, how are we assessing a place for people to be outside? Is there a location where we can have an approved campsite that is run differently than the one that we did in 2022? The one that we had done last time wasn’t a success. There were a whole host of challenges. But we have a lot of community partners at the table that are saying we could do this more successfully.

MTFP: You’re Missoula’s first new elected mayor since 2005, when John Engen first stepped into office. What do you think will be the most obvious difference between your approach to the job and his?

Davis: I’ve been doing quite a bit of work at the state level. I chair a Montana Housing Coalition, I’ve been active with establishing that coalition for a number of years and getting a statewide housing policy addressed and passing legislation. It was something that I encouraged Mayor Engen to do, and whether he wanted to or didn’t or whatever, it just was an area that he didn’t really lean into. I think that is one of the main differences you’ll see with me as mayor is I will be working hard to establish relationships and really a coalition of other major cities and towns across the state, because we share a lot of the same challenges right now … We’re going to need to be working on statewide property tax issues, we’re going to need to be working across the aisle, and homelessness [is] a significant issue that we cannot do alone. The stronger our neighboring cities are in their approach to solutions for homelessness, the better off we all are.

Mayor-elect #2

Joey Morrison, Bozeman

MTFP: Among the most pressing issues facing Bozeman is housing affordability. What specific actions can the city commission take within the next year to provide relief for residents who are struggling with that?

Morrison: It’s pretty limited at the moment. We could look at emergency measures like rental assistance and things like that to keep people in their homes, or looking at renter protections to keep folks from facing eviction. But as far as immediate relief, I don’t see that many tools in a one-year span. Longer term — being able to make it easier for folks to be able to internally subdivide existing structures [and] create private entrances [to] create private rentals that are part of an established existing structure, making it easier for folks to build [accessory dwelling units], maybe providing subsidies or rebates for folks that are willing to do that. Those are some of the things that I think are promising for short-term infill that doesn’t really modify the character of a neighborhood too much.

MTFP: Many of the things the city could do to address housing and related issues like homelessness would take quite a bit of money. Of course, property taxes are the major place city dollars come from and are also a major concern right now. How can the city do more without putting more burden on taxpayers?

Morrison: Some of it really needs to come from belt-tightening from the at-times-indulgent spending with out-of-state consultants that have enormous price tags to answer questions that we know the answers to. I really think that that will move the needle. I’ve sat on a few boards that were coming up hundreds of thousands of dollars a year to pay consultants.

We do have a lot of wealthy, affluent people that are philanthropic folks, that I do believe would be interested in making socially responsible investments or just contributions to some of these bigger projects, and I’d really like to see that start being a practice for us. If we’re going to try and get a $10 million bond before the voters, that we raise half of it as a city first.

MTFP: One of the dynamics you’ll face on the Bozeman commission is the possibility that the state’s conservative Legislature could override local action it sees as too progressive, as happened with inclusionary zoning in 2021. As you’re thinking about how to lead the city, how will you navigate that dynamic?

Morrison: I’ve really seen our local city commission shy away from sitting down and breaking bread with more rural neighbors and rural counties and cities that have real skin in the game to make sure they maintain local control. And I think we really need to start organizing alongside the Glendives and the Miles Cities and the Glasgows to make sure that they also recognize “Hey, when the state Legislature takes stuff away from Bozeman, they take stuff away from you too.”

Mayor-elect #3

Cory Reeves, Great Falls

MTFP: What’s at the top of your to-do list for when you take office?

Reeves: Top of our list is housing, just like every community, I think. To my understanding, in the state of Montana, everyone is having a housing crisis right now and Great Falls is not excluded. Our community development [department] is already making a lot of changes, but I want to do a top-to-bottom review of our zoning and permit processes to make sure that everything is streamlined. So when you show up to build a house in Great Falls or you show up to open a business in Great Falls, you don’t have to wait 6 to 9 to 12 months to get that business off the ground or that house built. I want to make sure everything is streamlined so it’s just kind of like a one-stop shop. And I do know that that is currently in the works. They’re working on that. But I’m going to really make sure when I take office Jan. 1 that people know that Great Falls is open for business. We want you to come here, we welcome you here.

MTFP: Voters shot down the public safety levy on the ballot in Great Falls — what will that mean for your incoming administration?

Reeves: The public safety levy and bond was a “heck no” from the community. It got slaughtered, if you will. So now we, as the commission, are going to have to come, sit back and go, ‘OK, with community input, where do we go from here?’ Because, unfortunately, this can has been kicked down the road for 50 years by previous commissions. The last public safety levy, as you’re probably aware, was in, I think, 1959. And so here in 2023, we tried to go after it and the community said, “No, we’re done being taxed.” And I think timing was bad also. You know, the state of Montana gave out the new tax appraisals, so everyone’s taxes went up. We recently had a public library levy that passed that was very controversial in our community. So I think people just said, “You know what, we’re done giving our tax dollars,” which I totally respect. It was a big ask for the community. But now we as a city commission and the community are going to have to sit down and have some hard conversations about “Where do we go from here?”

(Bozeman mayoral candidate John Meyer is married to MTFP reporter Amanda Eggert, who didn’t participate in reporting or editing this story.)

The post What Montana’s mayor-elects say they’ll do appeared first on Montana Free Press.

New research finds shrinking number of glaciers across the West

When the pandemic hit, Andrew Fountain began looking for a project he could do from home. Uninterested in getting a sourdough starter or taking up woodwork, Fountain began counting glaciers.

More than three years later, Fountain, a geology professor emeritus at Portland State University, and research assistant Bryce Glenn have released a revised inventory of glaciers in the American West that will soon be added to the U.S. Geological Survey’s national map. The new inventory by Fountain and Glenn shows that 52 of the 612 officially named glaciers are no longer glaciers because they are either too small, no longer moving or have disappeared altogether. In Montana, six named glaciers have been added to the “missing” list.

Fountain said their effort focused on the named glaciers across the western half of the continental United States because those were the most culturally significant. However, their inventory found that since the mid-20th century — about the time the USGS first started mapping the entire country — about 360 glaciers have either disappeared or become permanent snowfields. Fountain said the disappearance of glaciers shows just how much climate change is impacting the landscape across the American West.

For a glacier to be a glacier, it must be at least 0.01 square kilometers (roughly the size of two side-by-side football fields) and it must be moving. Fountain said you can tell if a glacier is moving if it still has crevices.

In Montana, Fountain found six named glaciers that no longer qualify as a glacier, including ones in Mission-Swan Range, the Crazy Mountains, the Cabinet Mountains and the Lewis Range in Glacier National Park. Fountain said Montana has lost 76 glaciers since the mid-20th century.

The USGS’ 7.5-minute maps — often printed on large pieces of paper that at one time, before the popularity of GPS maps, you could buy at the local outfitter — were first produced in the mid-20th century. All of the maps have been updated at least once, with others being updated more than once. But all of those updates missed one important detail, Fountain said.

“For whatever reason, whenever they updated the maps, they always updated the infrastructure — roads, buildings and those types of things — but they never updated the glaciers,” he said.

Using the USGS maps as a base, Fountain was able to use aerial images from the U.S. Department of Agriculture (which are taken every few years) to see just how much various glaciers across the West have shrunk.

“It was a great COVID project because we were all stuck at home so it was kind of nice to sit at a computer and just look a beautiful landscapes all day,” he said.

While it would be possible to conduct the research in the field, Fountain said, traveling to every glacier and taking measurements, trying to determine if it was still active, would have been overly time-consuming.

Some glaciers have become perennial snowfields whereas others are rock glaciers, more rock than ice.

“It was always a relief to find that a glacier was still a glacier,” Fountain said. “We were always cheering for them.”

With the initial report out, Fountain and his team are now digging further into the data to see why some glaciers have shrunk faster than others and to put a number of just how much glacier ice has disappeared in recent decades. Fountain said the work his team is doing is beneficial to show just how much climate change is altering the landscape.

In-depth, independent reporting on the stories impacting your community from reporters who know your town.

The post New research finds shrinking number of glaciers across the West appeared first on Montana Free Press.

Post-Roe, North Dakota puts resources into alternatives to abortion

North Dakota this year adopted one of the strictest abortion bans in the country, with narrow exceptions for rape and incest victims in the first six weeks of pregnancy and to save the life of the mother.

Although abortions-rights advocates haven’t given up the fight, abortion opponents are moving ahead with the restrictions and placing a heavier emphasis on supporting new mothers through legislation and services, such as maternity homes for pregnant women and teens.

One of those teens is Molly Richards, who was just 13 years old when she learned she was pregnant.

She remembers feeling both “excited and oblivious” when she got the results at a clinic on the Pine Ridge Reservation in South Dakota, where she grew up. The community is home to the Oglala Sioux Tribe, of which Richards, now 17, is a citizen.

“It was a very happy time for me,” she recalled.

Then the reality of carrying and raising a child began to sink in. But Richards didn’t view abortion as an option.

“Abortion was not on my mind. That was a big no-no for me.”

Seeking resources, Richards and her family connected with Mary Pat Jahner, director of Saint Gianna & Pietro Molla Maternity Home in the small, unincorporated community of Warsaw.

The picturesque brick home – four stories tall and trimmed with ornate gold crosses – is an institution within the North Dakota anti-abortion movement.

Originally a convent for nuns and a boarding school, the home now serves young pregnant women – most from nearby Native American reservations. In addition to food and shelter, the facility provides counseling services, help completing high school, clothing, job training and parenting classes to mothers.

The facility houses two to four residents at a time. Richards was four months into her pregnancy when she arrived at the home.

“Our main purpose is just to provide a choice for moms who …might need a place to stay or might need a family,” Jahner said. “Most of the moms don’t have a safe place to be, they might be living couch to couch. They’re not living on the street per se, but they might not have their own place to call home.”

With abortions essentially unavailable in the state, where religion is deeply ingrained and diverse, efforts to support mothers and their children have taken on new prominence.

After the U.S. Supreme Court overturned Roe v. Wade in 2022 and returned abortion decisions to the states, researchers predicted the number of births would increase, as would the need to support pregnant people, young mothers and their children.

An analysis by the Johns Hopkins Bloomberg School of Public Health estimates that nearly 9,800 additional live births occurred in Texas from April 2022 through December 2022 after a six-week abortion ban took effect in that state in fall 2021.

The federal Congressional Budget Office has said it anticipates an increase in births because of the end of Roe but that contraceptive use and other abortion methods, such as medication abortion, will largely offset that increase.

Kathy Hirsh-Pasek, a psychology professor at Temple University and senior fellow at the Brookings Institution, doesn’t think the United States is prepared for an influx of births – and that policies nationwide aren’t doing enough.

“We are right now not a family friendly country. We may be pro-life, but we’re not pro-family. And if you’re going to make decisions that put more babies into the market, we need to support those babies,” she said. “I don’t care if you’re pro-Roe or anti-Roe, support children. They’re your future.”

Supporting pregnant people through legislation

State Sen. Sean Cleary, R-Bismarck, has been at the forefront of pushing for additional help for mothers and babies amid North Dakota’s abortion ban.

“There was an understanding that women are navigating a very difficult time in their lives, that the state could be doing more to support them and empower them,” Cleary said. “We wanted to be a state that was known for supporting families and supporting mothers.”

Gov. Doug Burgum, a Republican, signed bills this year to eliminate taxes on diapers; expand Medicaid and Temporary Assistance for Needy Families benefits for pregnant individuals; and provide additional funding to the state’s “alternatives-to-abortion” program, which gives funds to child-placement agencies, anti-abortion counseling centers and maternity homes – including Gianna & Pietro.

Cleary co-sponsored the diaper tax and Medicaid bills, as well as failed efforts to create a paid family leave program, a tax credit for child care expenses and a program to increase pay for child care workers.

The 31-year-old said being a father helped him see the need for this type of legislation. He has a toddler and another child on the way.

“Families can’t afford to send their kids to child care, and the workers can’t afford to work there,” he said.

Abortion-rights activists doubt the effectiveness of the few measures that made it through the Legislature.

“None of them are actually adequate to address fully supporting a pregnant person bringing a child into the world and raising a child to adulthood,” said Cody Schuler, advocacy manager for the American Civil Liberties Union of North Dakota.

“If you’re going to have a near-total ban on abortion and you’re going to force people to carry pregnancy to term, you have to do more than give a tax break for diapers.”

Katie Christensen, North Dakota state director for Planned Parenthood, emphasized the problematic funding of the alternatives-to-abortion program.

Christensen has criticized the program for providing $1 million in state funds to mostly religious ministries with little to no government oversight. State funding for so-called “crisis pregnancy centers,” which aim to dissuade people from getting abortions, is especially concerning to abortion-rights advocates.

There are at least seven such centers in the state, according to the Crisis Pregnancy Center Map, which provides nationwide tracking of these facilities and is maintained by University of Georgia professors.

“We’re putting thousands of public dollars into programming that aims to seek out people who want abortions and try to persuade them away from that,” Christensen said. “They’re still allowed to promote their religion while using these dollars.”

Despite this criticism, Sen. Tim Mathern, D-Fargo, one of only four Democrats in the 47-member state Senate, co-sponsored the alternatives-to-abortion funding bill, claiming that it “sort of became a litmus test between pro-choice and pro-life people.”

Although he supports abortion access, Mathern backed the bill in an attempt to change the tide of Democrats in North Dakota being seen as “the anti-religion and anti-God people and the people who kill babies.”

However, if concerns over these “crisis pregnancy centers” are legitimate, Mathern said, their practices should be evaluated and “the state’s attorney should be investigating.”

‘Small government’ approach to helping mothers

North Dakota’s Legislature meets for 80 days during odd-numbered years only. Legislators, who don’t have staff, work at their desks on the floor of the Senate or House. This model can mean less government funding for programs, something Republican state Sen. Janne Myrdal supports.

Myrdal represents far northeastern North Dakota, where the Gianna & Pietro home is located. She sponsored the state’s strict new abortion ban and co-sponsored the bill that beefed up funding to the state’s alternatives-to-abortion program. She warns that such funding comes with some strings attached.

“If you ask for that much support, then the government’s going to come on top of it and go, ‘We’re going to regulate you,’” Myrdal said. “You can’t pray for people, you can’t hug people, you can’t share Jesus with people who come in, because the government can’t do that.”

Gianna & Pietro, which is a nonprofit organization, receives the majority of its funding – about $500,000 to $600,000 each year – from individual donors, but it also has received funds from the state’s alternatives-to-abortion program.

In this year’s bill, about $100,000 was earmarked for the home; Jahner said the money will go toward updating vehicles and other needs.

In the nearly two decades of the home’s operation, more than 300 people have lived there, and over 100 children have been born as part of the program.

During a recent visit, three women who were either pregnant or young mothers, including Richards, lived at the home. Staff members stay on site, too, to provide support and help.

Jahner, her daughter, whom she adopted from a former resident, and several other children of former residents live on the property, as well, in a two-story home behind Gianna & Pietro.

Richards’ initial stay in 2019 only lasted a month. Feeling homesick, she returned to South Dakota to give birth. But after struggling to parent on her own and dropping out of school, Richards returned to Gianna & Pietro over a year and a half ago, with her son, Bernard, in tow.

Richards is now in the process of having her son adopted by a family in southern Minnesota, because, she said, “I wanted something more and better for my son.”

There is a clear religious aspect to Gianna & Pietro. Residents must attend Sunday Mass, take part in nightly prayer and participate in grace before meals. A stained glass chapel is located on the first floor of the home, and delicate religious paintings are scattered throughout. Across the street sits a steepled red brick church where residents may also attend Mass.

Although residents are not required to be Catholic or religious to live at the home, a question about religious preference is included on the admission application form and participation in religious activities is required.

“I didn’t become religious until I actually came here, so my family isn’t religious,” Richards said. “I was baptized (Catholic) a year and a half ago.”

Schuler, of the ACLU, and other abortion-rights advocates worry such religious requirements could lead to “coercing individuals into religion” with the help of government funding.

“When it comes to a maternity home, it’s being operated as a religious ministry. I don’t think state dollars should be paying for that,” Schuler said. “But at the same time, I know that there are individuals who are religious who might be looking for what that center might provide.”

Expansion of reproductive care in Minnesota

With limited capacity in homes like Gianna & Pietro, abortion care across the Red River in neighboring Minnesota remains essential, abortion-rights advocates say.

“The amount of pregnant people who are having their abortions today across the river would fill up those homes fivefold today – unless they’re going to open up huge apartment complexes to house all of these pregnant people,” said Destini Spaeth, board chair of the North Dakota Women in Need Abortion Access Fund.

Abortion is legal in Minnesota up to fetal viability, which is 24 to 26 weeks, and exceptions are granted to save the life or protect the health of the mother. Surrounded by states that have completely banned abortion or are in court fighting to prevent access, Minnesota has become a key state for abortion access in the Upper Midwest.

For nearly 25 years, Red River Women’s Clinic operated in Fargo and was the only abortion clinic in the state for two decades. Every Wednesday, when the clinic was open, protesters gathered with graphic signs outside the front door.

Then last year, after word of the Supreme Court’s likely end to Roe was leaked, its operators began looking for a new location. Last August, they reopened less than 3 miles away – across the river in Moorhead, Minnesota.

Each Wednesday, the clinic provides 25 to 30 abortions up to the 16-week mark of pregnancy. After that time, patients are referred elsewhere for a multiday procedure that the independent clinic lacks capacity for.

Since the move, the clinic has seen its patient load increase 10% to 15%, said Tammi Kromenaker, the facility’s director. And with fewer overall restrictions on abortion care in Minnesota, Kromenaker said she believes access has actually increased for women in North Dakota.

But the fear her patients feel has also gone up, she said.

“Every week, mostly patients from North Dakota will say: ‘Is it even legal for me to come here? Will I get legally prosecuted for this health care?’

Kromenaker continues to fight for abortion rights back across the river in North Dakota. Her clinic is one of the plaintiffs in a lawsuit over the state’s near-total abortion ban.

“We didn’t want to give up on North Dakota. We didn’t want to leave,” she said. “But our hand was forced.”

News21 reporters Trilce Estrada Olvera and Cassidey Kavathas contributed to this story.

This report is part of “America After Roe,” an examination of the impact of the reversal of Roe v. Wade on health care, culture, policy and people, produced by Carnegie-Knight News21. For more stories, visit https://americaafterroe.news21.com/.

The post Post-Roe, North Dakota puts resources into alternatives to abortion appeared first on Buffalo’s Fire.

Despite Supreme Court ruling, ICWA challenges remain

The nation’s highest court recently upheld the Indian Child Welfare Act in a major case over the law’s constitutionality, a decision hailed by many as a victory for Indigenous children and their families.

But while the 7-2 majority decision in the Brackeen v. Haaland case firmly rejected key arguments against the law known as ICWA, state-level challenges have been moving through lower courts across the country, with varying degrees of success.

Cases in Nebraska, Alaska, Iowa, Montana and Oklahoma center on different legal issues than those decided by the U.S. Supreme Court last month. Plaintiffs in Brackeen v. Haaland — a group of states along with white adoptive parents seeking custody of Native children — argued unsuccessfully that ICWA was unconstitutional because it exceeds the “plenary powers” of Congress to pass legislation governing tribal affairs, “commandeers” states to follow federal law and violates equal protection guarantees.

Yet while the Supreme Court upheld ICWA’s constitutionality for now, legal experts who are both supporters and critics of the 45-year-old federal law say the Brackeen case doesn’t rule out future challenges to tribal sovereignty.

What’s more, justices declined to delve into the equal protection arguments in the case, stating only that the plaintiffs “lack standing” on that issue because the adoptions of Indigenous children they sought had been finalized. Some court watchers say that leaves open the possibility of future lawsuits on equal protection issues.

The 1978 law in question seeks to repair damage caused by centuries of forced attendance at Indian boarding schools and coercive adoptions into white, Christian homes. That legacy has endured in Indian Country, where the rate of foster care removals remains far higher than in other racial and ethnic communities.

Under ICWA, state child welfare agencies must determine whether a child facing foster care, adoption or guardianship is a member of a Native American tribe. If they are an enrolled member or have a parent who is enrolled and are eligible for tribal membership, the case takes a different pathway than for other children. Tribes must be offered the opportunity to take jurisdiction from the state court; tribal members and Indigenous foster parents and kin must be prioritized for placements; and social service agencies must make “active” rather than “reasonable” efforts to help parents accused of maltreatment reunite with their children.

Kate Fort, director of the Indian Law Clinic at Michigan State University College of Law, outlined the most common reasons for an ICWA appeal in the March edition of the Juvenile and Family Court Journal.

She wrote that between 2017 and 2022, more than 40 percent of all such cases were remanded — sent back to lower courts — or reversed. Plaintiffs in 87 percent of the ICWA-based appeals were biological parents of an Indigenous child. About half the cases were appealed based on parents’ belief that the court improperly determined ICWA’s application to their child’s case.

“These data indicate that agencies and courts are still struggling with the first step in an ICWA case — whether they have an ICWA case at all,” Fort wrote in the paper.

Two ICWA-related cases were decided by the Alaska Supreme Court in July 2022.

They involved the federal law’s provision requiring that a “qualified expert witness” testify about the Indigenous child’s tribe, customs and traditions before their parent’s rights can be terminated. Those challenges did not prevail.

Recent disputes over ICWA in state courts center on tribal jurisdiction, the definition of a Native child, and termination of parental rights, among other issues. The following is a summary of some recent cases:

Oklahoma

Tribal court jurisdiction in child welfare cases lost ground in an April ruling in Oklahoma. In the decision — involving a child identified as S.J.W. — the state Supreme Court gave lower courts increased ability to grant custody of Native children living on a reservation that is not their own.

S.J.W.’s parents argued that “the Chickasaw tribal court has exclusive jurisdiction regardless of the fact that S.J.W. is a nonmember Indian child,” according to court documents. The state maintained it had shared jurisdiction on cases involving ICWA.

Critics call the ruling involving a Muscogee child living on Chickasaw Nation’s reservation deeply flawed.

The state Supreme Court “misunderstands tribal sovereignty,” the Choctaw Nation’s senior executive officer of legal and compliance Brian Danker told a National Public Radio affiliate. “This ruling could impact a tribe’s ability to protect tribal citizens’ social, cultural and familial connections as it attempts to chip away at the foundations of tribal sovereignty in the state of Oklahoma.”

Fort described the Oklahoma ICWA case as unique, and a “truly unfortunate opinion with absurdly weak analysis.” Fort said tribes’ ability to retain jurisdiction over child welfare cases remains an ongoing fight in multiple states.

Iowa and Nebraska

In another suit filed this past April by the Red Lake Band of Chippewa Indians, the Supreme Court in Nebraska denied the tribe’s request to intervene, because it had previously been determined the child in question did not meet the criteria of an “Indian child.” The child’s mother was eligible for tribal enrollment, but was not yet enrolled.

The tribe argued the spirit of ICWA should apply to the case, but the state of Nebraska opposed that position, and was victorious in court. Ultimately, the state’s highest court ruled that ICWA’s specific requirements to determine a child’s eligibility for its protections should be strictly applied.

In April 2022, the Iowa Supreme Court upheld a juvenile court’s ruling that denied a child ICWA protections, affirming a prior decision to terminate the rights of the child’s parent. The juvenile court found the state’s “reasonable efforts” to avoid out-of-home placement — instead of the “active efforts” required for tribal members under ICWA — were adequate because the child was deemed to be non-Native.

Montana

ICWA was affirmed in a Montana case decided by the state Supreme Court in January, a ruling that underscored how the federal law applies to guardianships and third-party custody proceedings, in addition to adoption and foster care cases.

The child’s mother, an enrolled member of the Native Village of Kotzebue Tribe in Alaska, provided the court with verification that her three children were eligible for ICWA protections. She asked the courts to remove her children from the Montana home of their paternal grandparents — who had full custodial rights — and restore her custody. The case was sent back to lower courts for further proceedings to determine if the children should be returned to their mother.

Minnesota

Nearly two weeks after the Brackeen decision in mid-June, the U.S. Supreme Court denied review of a recent Minnesota case making a related equal protection argument — that ICWA discriminates against non-Native foster and adoptive parents.

In March 2022, Hennepin County was sued by two Indigenous foster parents who were unsuccessful in the adoption of the Indigenous child they were fostering. Instead, the child’s tribe, Red Lake Band of Chippewa, took over the proceedings and granted custody to the child’s maternal grandmother. The foster parents were considered “nonmembers” in the ICWA case, because one is enrolled in the Bois Forte Band of Chippewa and the other is a White Earth Nation descendant.

The plaintiffs in the case — who, under ICWA, lost priority in their adoption efforts in favor of the child’s relative despite having adopted the child’s siblings — were represented by Minnetonka attorney Mark Fiddler, a member of the Turtle Mountain Band of Chippewa Indians. He also represented the white adoptive couples seeking to overturn ICWA in Brackeen v. Haaland. The conservative Goldwater Institute filed amicus briefs in both cases, challenging ICWA’s constitutionality.

In an email, Fiddler said that while the institute attacked ICWA as unconstitutional, the plaintiffs did not. “Rather, they argued ICWA could and should be interpreted to be constitutional by not forcing nonmembers into a jurisdiction foreign to them,” he said.

“Petitioners were improperly subjected to the personal and subject matter jurisdiction of a state foreign to them, one where they have no right to vote,” plaintiffs stated in Denise Halvorson v. Hennepin County Children’s Services Department case documents. As a result, the lower court violated “their due process rights to fundamental fairness and equal protection.”

But the petition to the U.S. Supreme Court was denied on June 26.

Fiddler said despite the high court upholding ICWA in Brackeen and its denial of the Hennepin County case, establishing standing in an equal protection case against ICWA “would be easy,” and he fully expects continued challenges to the law on this issue and others.

“Any foster or adoptive parent would have the right to move to strike down ICWA in state court, so long as he or she was jeopardized by it somehow,” Fiddler stated shortly after the Brackeen decision.

The Imprint is a non-profit, non-partisan news publication dedicated to reporting on child welfare.

The post Despite Supreme Court ruling, ICWA challenges remain appeared first on Buffalo’s Fire.

How climate science won in the Montana youth climate case

“Every additional ton of GHG emissions exacerbates plaintiffs’ injuries and risks locking in irreversible climate injuries,” the decision reads. Striking down laws that keep state agencies from considering emissions, Seeley decided, has “significant health benefits” for the children and young adults suing their government. In response, the plaintiffs expressed elation, joy and disbelief. “We are heard!” Kian Tanner said in a statement.

“We are heard!”

Seeley walked through her reasoning for the decision in a 103-page ruling, which affirmed that climate is a “part of the environmental life-support system” guaranteed by the Montana Constitution. She agreed that the harm caused by climate change is significant — hurting the plaintiffs’ mental and physical health, limiting their access to traditional food sources and threatening family ranching operations, among other things — and that it is linked to state policies. “It was better than hoped for,” said Michael Gerrard, director of Columbia Law School’s Sabin Center for Climate Change Law.

The decision reads as a lesson in the “overwhelming scientific consensus” of climate change. Seeley points out that state’s leadership has known about the dangerous impacts of climate change for at least the last 30 years. She also notes that ecosystems are interconnected, and that treating Montana’s actions in a vacuum is not scientifically supported. The findings spend numerous pages discussing youth’s unique vulnerability to climate change and its impacts, as well as how climate change is already impacting Montana’s environment and economy. In a statement, Our Children’s Trust, the nonprofit law firm which led this and other trailblazing youth climate cases, said it believes that these facts “set forth critical evidentiary and legal precedent for the right of youth to a safe climate.”

By considering climate change’s impacts when approving or denying permits for fossil fuel activities, including coal and natural gas-powered energy plants, coal mining and oil and gas refineries, Seeley wrote, the state can safeguard its citizens’ constitutional rights. The ruling notes that this is possible, because it’s technically and economically feasible to replace the majority of Montana’s fossil fuel energy by 2030.

The immediate direct ramifications in Montana, though, are “extremely narrow,” Gerrard said. The ruling requires the state to consider climate change when making energy decisions — but agencies could simply consider it and move forward with projects anyway. “The much greater significance is that we now have a ruling that affirms climate science after a trial and says that where there is a constitutional right to a clean environment, that can have consequences on climate change,” he said.

The complaint, led by Our Children’s Trust, focused on the Montana Environmental Protection Act, or MEPA, as well as two laws limiting the state’s consideration of climate change passed by the Montana Legislature this spring. MEPA established a process to assess the environmental consequences of state actions but has been repeatedly limited in scope. HB 971 narrowed its purview again this year by prohibiting state agencies from considering greenhouse gas emissions; SB 557 contained similar restrictions, stating that concerns about emissions could not stop or delay permitting.

The state has approved or expanded numerous large-scale projects, including coal mines and gas-fired power plants, in recent years without including climate impacts in its analysis. The ruling argues that emissions from these and other projects in Montana are “nationally and globally significant,” measured by both local effects and their contribution to global climate change.

“More rulings like this will certainly come.”

Montana’s unique constitution provided the backbone for the legal challenge. It’s one of six states — and the only one in the West — with constitutionally based environmental protections. The Held v. Montana ruling, experts say, underscores the importance of having similar constitutional environmental protections for this particular strategy to work. “This is a huge win for Montana, for youth, for democracy, and for our climate,” said Julia Olson, chief legal counsel and the executive director of Our Children’s Trust, in a statement. “More rulings like this will certainly come.”

Youth climate cases are set to continue into next year, with trials slated for the federal Juliana v. United States and state Navahine F. v. Hawaiʻi Department of Transportation cases, both led by lawyers with Our Children’s Trust. Hawai‘i already has environmental protections in its constitution. There’s also a push to add Montana-esque environmental protections, so-called “green amendments,” to other state constitutions — including Nevada’s.

In Montana, the legal process is likely to continue. The state attorney general’s office said it would appeal the decision to the Montana Supreme Court, with a spokesperson telling The Flathead Beacon it was “absurd.”

Kylie Mohr is a correspondent covering wildfire for High Country News. She writes from Montana. Email her at kylie.mohr@hcn.org or submit a letter to the editor. See our letters to the editor policy.